Hindenburg-class airship

| Hindenburg class | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hindenburg at NAS Lakehurst | |

| Role | Passenger airship |

| National origin | Germany |

| Manufacturer | Luftschiffbau Zeppelin |

| Designer | Ludwig Dürr |

| First flight | March 4, 1936 (LZ 129)

September 14, 1938 (LZ 130) |

| Retired | 1937 (LZ 129)

1939 (LZ 130) |

| Status | Destroyed by fire (LZ 129); Scrapped (LZ 130)) |

| Primary user | Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei |

| Number built | 2 |

|

| |

The two Hindenburg-class airships were hydrogen passenger carrying rigid airships built in Germany in the 1930s and named in honor of Paul von Hindenburg. They were the last such aircraft ever built, and in terms of their length and volume, the largest aircraft ever to fly. During the 1930s, airships like the Hindenburg class were widely considered the future of air travel, and the lead ship of the class, LZ 129 Hindenburg, established a regular transatlantic service. The destruction of this same ship in a spectacular and highly publicized accident was to prove the death knell for these expectations. The second ship, LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin was never operated on a regular passenger service, and was scrapped in 1940 by the order of Hermann Göring.

Design and development

Yellow: USS Enterprise, supercarrier

Dark blue: Yamato, WWII Japanese warship

Grey: Empire State Building

Red: Mont, a supertanker

The Hindenburg class were built to an all-duralumin design. The leader of the design team was Dr. Ludwig Dürr, who had overseen the design of all Zeppelins except LZ-1 (on which he was a crew member), under the overall direction of Hugo Eckener, the head of the company. They were 245 m (804 ft) long and 41 m (135 ft) in diameter, longer than three Boeing 747s placed end-to-end, longer than four Goodyear GZ-20 "blimps" end-to-end, and only 24 m (79 ft) shorter than the RMS Titanic. The previous largest civilian airship was the British R101 at 777 ft (236.83 m) long and 40 m wide completed in 1929. The US Navy's Akron and Macon were 239 m (785 feet) long and 144 feet wide.

The design originally called for cabins for 50 passengers and a crew complement of 40.

Construction of the first ship, LZ 129, later named Hindenburg, began in 1931, but was suddenly stopped when Luftschiffbau Zeppelin went bankrupt. This led Eckener to make a deal with the Nazi Party which came to power in 1933. He needed money to build the airship, but in return he was forced to display the swastikas on the tail fins. Construction then resumed in 1935. The keel of the second ship, LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin was laid on June 23, 1936, and the cells were inflated with hydrogen on August 15, 1938. As the second Zeppelin to carry the name Graf Zeppelin (after the LZ 127), she is often referred to as Graf Zeppelin II.

The duralumin frame was covered by cotton cloth varnished with iron oxide and cellulose acetate butyrate impregnated with aluminium powder. The aluminium was added to reflect both ultraviolet, which damaged the fabric, and infrared light, which caused heating of the gas. This was an innovation that was first used on the LZ 126 which was taken as war reparations by the US and served as the USS Los Angeles (ZR-3) from 1924 until decommissioned in 1933. Following the destruction of Hindenburg, the doping compound for the outer fabric covering of Graf Zeppelin was changed: bronze and graphite were added to prevent flammability and improve the outer covering's electrical conductivity.

The rigid structure was held together by many large rings up to the size of a Ferris wheel, 15 of which were gas cell boundaries which formed bulkheads. These bulkheads were braced by steel wires which connected up into the axial catwalk. The longitudinal duralumin girders connected all the rings together and formed "panels". The 16 gas cells were made of cotton and a gas-tight material. On Graf Zeppelin, the cells were lightened and one was made of lightweight silk instead of cotton.

Hydrogen was vented out through valves on the top of the ship. These valves could be controlled both manually and automatically. The axial catwalk was added across the center of the ship to provide access to the gas valves. A keel catwalk provided access to the crew quarters and the engines. Alongside the keel were water ballast and fuel tanks. The tail fins of the airship were over 100 ft (30 m) in length, and were held together with a cross-like structure. The lower tail fin also had an auxiliary control room in case the controls in the gondola malfunctioned.

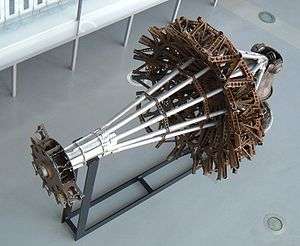

Hindenburg was powered by four reversible 890 kW (1,190 hp) Daimler-Benz diesel engines which gave the airship a maximum speed of 135 km/h (84 mph). The engine pods were completely redesigned for Graf Zeppelin, using diesel engines powering tractor propellers. The engines had a water recovery system which captured the exhaust of the engines to minimize weight lost during flight.

To reduce drag, the passenger rooms were contained entirely within the hull, rather than in the gondola as on the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, on two decks. The upper deck, "A", contained the passenger quarters, public areas, a dining room, a lounge, and a writing room. The lower deck, "B", contained washrooms, a mess hall for the crew, and a smoking lounge. Long slanted windows ran the length of both decks. The passenger decks were redesigned for Graf Zeppelin; the restaurant was moved to the middle of the quarters and the promenade windows were half a panel lower.

Lift gas

Hindenburg was originally designed for helium, heavier than hydrogen but nonflammable. Most of the world's supply of helium comes from natural gas fields in the United States, which had banned its export under the Helium Control Act (1927). Eckener expected this ban to be lifted, but to save helium the design was modified to have double gas cells (an inner hydrogen cell protected by an outer helium cell).[1] The ban remained however, so the engineers used only hydrogen despite its extreme flammability.[2] It held 200,000 cubic metres (7,062,000 cu ft) of gas in 16 bags or cells with a useful lift of approximately 232 t (511,000 lb). This provided a margin above the 215 t (474,000 lb) average gross weight of the ship with fuel, equipment, 10,000 kg (22,000 lb) of mail and cargo, about 90 passengers and crew and their luggage.

The Germans had extensive experience with hydrogen as a lifting gas. Accidental hydrogen fires had never occurred on civilian Zeppelins, so the switch from helium to hydrogen did not cause much concern. Hydrogen also increased lift by about 8%. After the Hindenburg disaster Eckener vowed never to use hydrogen again in a passenger airship. He planned to use helium for the second ship and went to Washington, D.C. to personally lobby President Roosevelt, who promised to supply the helium only for peaceful purposes. After the annexation of Austria in March 1938, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes refused to supply the gas, and the Graf Zeppelin was also filled with hydrogen.

Operational history

LZ 129 Hindenburg

Hindenburg made her first flight on 4 March 1936, but before commencing her intended role as a passenger liner, was put to use for propaganda purposes by the Nazi government. Together with LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, she spent four days dropping leaflets, playing music, and making radio broadcasts in the lead up to the March 29 plebiscite mandating Hitler's Chancellorship and remilitarization of the Rhineland.

Commercial services commenced on 31 March 1936 with the first of seven round trips to Rio de Janeiro that Hindenburg was to make during her first passenger season. Together with ten round trips to New York, Hindenburg covered 308,323 km (191,583 mi) that year with 2,798 passengers and 160 tons of freight and mail.

Following refurbishment during the winter, Hindenburg set out on her first flight to North America for the 1937 season (she had already made one return trip to South America in 1937) on 3 May, bound for New York. This flight would end in tragedy with Hindenburg being utterly consumed by fire as she prepared to dock at NAS Lakehurst in New Jersey.

LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II

By the time the Graf Zeppelin II was completed, it was obvious that the ship would never serve its intended purpose as a passenger liner; the lack of a supply of inert helium was one cause. The ship was christened and made her first flight on September 14, 1938, making a circuit from Friedrichshafen to München, Augsburg, Ulm, and back. The total distance covered was 925 km (575 mi). The Graf Zeppelin II made a total of thirty flights, mainly spy missions for the Luftwaffe.

Scrapping

In April 1940, Hermann Göring issued the order to scrap both Graf Zeppelin's and the unfinished framework of LZ 131, since the metal was needed for other aircraft. By April 27, work crews had finished cutting up the airships. On May 6, the enormous airship hangars in Frankfurt were leveled by explosives, three years to the day after the destruction of the Hindenburg.

Specifications

General characteristics

- Crew: ca. 40

- Capacity: ca. 50 passengers for LZ-129 (later upgraded to 72), 40 passengers for LZ-130

Hindenburg Length: 804.8' Graf Zeppelin II Length: 803' Diameters are the same.

- Diameter: 41.2 m (135 ft 0 in)

- Volume: 200,000 m3 (7,100,000 ft3)

- Useful lift: 10,000 kg (22,046 lb)

- Powerplant: 4 × Daimler-Benz DB 602 16-cylinder 1100HP Diesel Engine's., 735 kW (1100HP hp) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 131 km/h (81 mph)

See also

References

- Sammt, Albert. 1988. Mein Leben für den Zeppelin, Verlag Pestalozzi Kinderdorf Wahlwies 1988, ISBN 3-921583-02-0 - pages 167-168 extract covering LZ 130's spying trip from 2 to 4 August 1939, (German) (pdf)

External links

- Comparison between LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin and LZ 129 Hindenburg

- Airships.net: photographs of interior and exterior of LZ-129 Hindenburg

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||