Herman Moll

- This article is about the cartographer; for the convict, see Germán Moll (convict).

Herman Moll (1654? – September 22, 1732), was a London cartographer, engraver, and publisher.

Origin and early life

Moll's exact place of origin is unknown, although his birth year is generally accepted to be the year 1654. He moved to England in 1678 and opened a book and map store in London. He produced maps from his studies of the work of other cartographers.[1][2]

Due to Moll's important work in Dutch cartography and the fact that he undertook a journey in his late years on behalf of the Netherlands, it is assumed he originated from Amsterdam or Rotterdam. The name, "Moll" occurred not only in the Netherlands however but also in the north German area, which may suggest a German origin. Dennis Reinhartz's biography assumed that Moll came from Bremen, and other more recent works assume Germany as well.[3][4]

Cartographic work

Early years in London

Moll produced his earliest maps from studying cartographers such as John Senex and Emanuel Bowen.[5] He probably sold his first maps from a stall in various places in London. From 1688 he had his own shop in Vanley's Court in London's Blackfriars. Between 1691 and 1710 his business was located at the corner of Spring Gardens and Charing Cross, and he finally moved along the River Thames to Beech Street where he remained until his death.

In the 1690s, Moll worked mainly as an engraver for Christopher Browne, Robert Morden and Lea, in whose business he was also involved. During this time he also published his first major independent work, the Thesaurus Geographicus. The success of this work likely influenced his decision to start publishing his own maps.

Work as an independent publisher

In 1701 he published A System of Geography, the first of his own publishing. Although it contained no fundamental changes in the presentation of his previous work, it helped him to assert himself as a freelance cartographer. Over the years, the work itself as well as individual maps were of influence on other publishers, as they were frequently copied and re-issued.

In the years that followed he brought out several volumes including Fifty-six new and accurate maps of Great Britain, a book of maps of the British Isles. Then came The Compleat Geographer which was an update to A System of Geography. He issued forty-two monochrome maps designed without the usual text, as by not using his usual colors he could produce them at significantly less expense than comparable works, and went through many new editions. In 1711 he began his Atlas Geographus, which appeared in monthly deliveries from 1711 to 1717, and eventually comprised five volumes. This included a full geographical representation of the world in color maps and illustrations. Moll's subscribers. As with his earlier works, the Atlas Geographus was eagerly copied and imitated.

In 1710 he began producing artfully crafted pocket globes . These were each a pair of globes, with the larger, hinged celestial globe encircled a smaller globe. On the latter he often included the route of Dampier's circumnavigation. These globes are very rare today.[6]

In 1715 Moll issued The World Described, a collection of thirty large, double-sided maps which saw numerous editions. In these maps Moll's skill as an engraver is particularly clear. These were bound separately and then later sold in the form of atlases in a joint venture between a number of other publishers.

The series included two of the most famous Moll maps: A new and exact map of the dominions of the King of Great Britain and To The Right Honorable John Lord Sommers...This Map of North America According To Ye Newest and Most Exact Observations. These were distinctive for their elaborate cartouches and images, and are known respectively as the Beaver Map and the Codfish Map. As with much of his work, Moll used these maps to publicize and support British policy and regional claims throughout the world.[7][8]

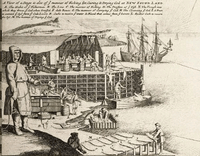

The Codfish Map shows in its cartouches a scene from the cod fisheries off Newfoundland. Since the beginning of the 16th Century the cod fishery there was an important economic factor for the European colonial powers. At the time of issue, the battle over fishing rights was one of the central points of contention in the North American policy of France and England. With its depiction of the processing of freshly caught cod for shipment to Europe, Moll highlighted for subscribers and viewers the importance of this sector for his native England.[9]

Moll labeled the Atlantic Ocean as the "Sea of the British Empire" and stressed that the British claims to fishing rights off the coast of Newfoundland. In a West India map from the same series, he wrote in the southwestern corner of Carolina, the words "Spanish Fort Deserted" and "Good Ground". On many of its North American maps - including at the Beaver Map - he drew particular attention to major ports streets, because he knew that was a sufficient infrastructure detail, communicating that for the further expansion of English is very important.[10]

Pritchard argues that the Beaver Map was "one of the first and most important cartographic documents relating to the ongoing dispute between France and Great Britain over boundaries separating their respective American colonies ... The map was the primary exponent of the British position during the period immediately following the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713."[11]

His maps were also used by other powers to attempt support for their claims. One of Moll's maps of the Island of Newfoundland Island, published in the 1680s, showed Pointe Riche, the southern limit of the French Shore to be situated at 47°40' north latitude. In 1763 the French attempted to use this map to establish their claim to the west coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, arguing that Point Riche and Cape Ray were the same headland. Governor Hugh Palliser and Captain James Cook found evidence to refute Moll's claim and in 1764 the French accepted the placement of Pointe Riche near Port au Choix.

However, all political considerations aside, Moll's maps were in his lifetime and after very influential, and are still among the most sought after aesthetic engravings in the history of cartography.

Contemporaries

Moll was quite involved in the contemporary intellectual life. He was friendly and acquainted with Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke and William Dampier, both socially and likely through the Royal Society.[12][13] His relationship with Dampier, especially, was mutually very beneficial. Moll had access to the latest data and observations from Dampier's many voyages, allowing his to be the first to accurately portray the great ocean currents, and Dampier in turn had his best selling books illustrated by Moll.[14]

Daniel Defoe was another contemporary with whom Moll exchanges ideas, and for whom he provided illustrations and maps. Another acquaintance, Jonathan Swift, went so far as to include him in his famous book, Gulliver's Travels, having Lemuel Gulliver remark in chapter four, part eleven: "I arrived in seven hours to the south-east point of New Holland. This confirmed me in the opinion I have long entertained, that the maps and charts place this country at least three degrees more to the east than it really is; which I thought I communicated many years ago to my worthy friend, Mr. Herman Moll, and gave him my reasons for it, Although he has rather chosen to follow other authors."

Death and legacy

Moll died on September 22, 1732, as noted in his obituary in Gentleman's Magazine.[15]

Selected works

- Thesaurus Geographicus. A new body of geography: or a compleat description of the Earth Collected with great care from the most approv'd geographers and modern travellers and discoveries by several hands (1695)

- A System of Geography (1701)

- The Compleat Geographer (1709)

- The British empire in America (1708)

- A View of the Coasts, Countries, and Islands within the limits of the South Sea Company (1711)

- The World Described (1715)

- A Set of Fifty New and Correct Maps of England and Wales (1724)

- A Tour Thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain: Divided Into Circuits or Journies 4 volumes. (1761)

Gallery

-

Inset of Moll's so called Beaver Map from The World Described, a scene he copied from a map by Nicolas de Fer[1]

-

Inset of Moll's so called Codfish Map from The World Described

-

Moll's A New & Exact Map of the Coast, Countries and Islands within ye Limits of ye South Sea Company London 1711 (1720)

- ^ "Detecting the Truth. Fakes, Forgeries and Trickery". Library and Archives Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

References

Notes

- ↑ Barber, p. 190.

- ↑ Reinhartz.

- ↑ Barber, p. 190.

- ↑ Reinhartz.

- ↑ Reinhartz, p. 55.

- ↑ For a picture of what is likely a Moll pocket globe, or at least very similar, see External Links.

- ↑ Reinhartz, p 37, pp 135-6.

- ↑ Barber, p 190.

- ↑ Reinhartz, p 37, pp 135-6.

- ↑ Reinhartz, p 37, pp 135-6.

- ↑ Pritchard.

- ↑ Preston, p. 230.

- ↑ Reinhartz.

- ↑ Preston, p. 239.

- ↑ Reinhartz, p. 25.

Bibliography

- Barber, Peter. "The Map Book". Walker & Company, 2005. New York.

- Gohm, Douglass. "Antique Maps of Europe, the Americas, West Indies, Australasia, Africa, the Orient" Octopus Books, 1972. London.

- Preston, Diana & Michael. "A Pirate of Exquisite Mind: Explorer, Naturalist, and Buccaneer: The Life of William Dampier". Walker & Company, 2004.

- Pritchard, Margaret Beck. "Degrees of Latitude : Mapping Colonial America". Harry Abrams, 2002.

- Reinhartz, Dennis "The Cartographer and the Literati: Herman Moll and His Intellectual Circle". Edwin Mellen Press, 1977. Lewiston NY.

External links

- Celestial Pocket Globe at the Royal Museums Greenwich

- de.wikipedia.org, Herman Moll (featured article in German)

|