Herfindahl index

The Herfindahl index (also known as Herfindahl–Hirschman Index, or HHI) is a measure of the size of firms in relation to the industry and an indicator of the amount of competition among them. Named after economists Orris C. Herfindahl and Albert O. Hirschman, it is an economic concept widely applied in competition law, antitrust[1] and also technology management.[2] It is defined as the sum of the squares of the market shares of the firms within the industry (sometimes limited to the 50 largest firms),[3] where the market shares are expressed as fractions. The result is proportional to the average market share, weighted by market share. As such, it can range from 0 to 1.0, moving from a huge number of very small firms to a single monopolistic producer. Increases in the Herfindahl index generally indicate a decrease in competition and an increase of market power, whereas decreases indicate the opposite. Alternatively, if whole percentages are used, the index ranges from 0 to 10,000 "points". For example, an index of .25 is the same as 2,500 points.

The major benefit of the Herfindahl index in relationship to such measures as the concentration ratio is that it gives more weight to larger firms.

The measure is essentially equivalent to the Simpson diversity index, which is a diversity index used in ecology, and to the inverse participation ratio (IPR) in physics.

Example

For instance, we consider two cases in which the six largest firms produce 90% of the goods in a market. In either case, we will assume that the remaining 10% of output is divided among 10 equally sized producers.

- Case 1: All six of the largest firms produce 15% each.

- Case 2: The largest firm produces 80% and the next five largest firms produce 2% each.

The six-firm concentration ratio would equal 90% for both case 1 and case 2. But the first case would promote significant competition, where the second case approaches monopoly. The Herfindahl index for these two situations makes the lack of competition in the second case strikingly clear:

- Case 1: Herfindahl index = (0.152+0.152+0.152+0.152+0.152+0.152) + (0.012+0.012+0.012+0.012+0.012+0.012+0.012+0.012+0.012+0.012)= 0.136 (13.6%)

- Case 2: Herfindahl index = 0.802 + 5 * 0.022 + 10 * 0.012 = 0.643 (64.3%)

This behavior rests in the fact that the market shares are squared prior to being summed, giving additional weight to firms with larger size.

The index involves taking the market share of the respective market competitors, squaring it, and adding them together (e.g. in the market for X, company A has 30%, B, C, D, E and F have 10% each and G through to Z have 1% each). If the resulting figure is above a certain threshold then economists consider the market to have a high concentration (e.g. market X's concentration is 0.142 or 14.2%). This threshold is considered to be 0.25 in the U.S.,[1] while the EU prefers to focus on the level of change, for instance that concern is raised if there is a 0.025 change when the index already shows a concentration of 0.1.[4] So to take the example, if in market X company B (with 10% market share) suddenly bought out the shares of company C (with 10% also) then this new market concentration would make the index jump to 0.162. Here it can be seen that it would not be relevant for merger law in the U.S. (being under 0.18) or in the EU (because there is not a change over 0.025).

Formula

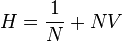

where si is the market share of firm i in the market, and N is the number of firms. Thus, in a market with two firms that each have 50 percent market share, the Herfindahl index equals 0.502+0.502 = 1/2.

The Herfindahl Index (H) ranges from 1/N to one, where N is the number of firms in the market. Equivalently, if percents are used as whole numbers, as in 75 instead of 0.75, the index can range up to 1002, or 10,000.

An H below 0.01 (or 100) indicates a highly competitive index.

An H below 0.15 (or 1,500) indicates an unconcentrated index.

An H between 0.15 to 0.25 (or 1,500 to 2,500) indicates moderate concentration.

An H above 0.25 (above 2,500) indicates high concentration.[5]

A small index indicates a competitive industry with no dominant players. If all firms have an equal share the reciprocal of the index shows the number of firms in the industry. When firms have unequal shares, the reciprocal of the index indicates the "equivalent" number of firms in the industry. Using case 2, we find that the market structure is equivalent to having 1.55521 firms of the same size.

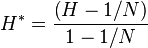

There is also a normalised Herfindahl index. Whereas the Herfindahl index ranges from 1/N to one, the normalized Herfindahl index ranges from 0 to 1. It is computed as:

for N > 1 and

for N > 1 and  for N = 1

for N = 1

where again, N is the number of firms in the market, and H is the usual Herfindahl Index, as above. Using the normed Herfindahl index, information about the total number of players (N) is lost, as shown in the following example: Assume a market with two players and equally distributed market share; H = 1/N = 1/2 = 0.5 and H* = 0. Now compare that to a situation with three players and again, an equally distributed market share; H = 1/N = 1/3 = 0.333..., whereas H* = 0 like the situation with two players. Apparently, the market with three players is less concentrated albeit not obvious looking at just H^*. Thus, normalized Herfindahl index can serve as a measure for equality of distribution but is less suitable for concentration.

Problems

The usefulness of this statistic to detect and stop harmful monopolies however is directly dependent on a proper definition of a particular market (which hinges primarily on the notion of substitutability).

- For example, if the statistic were to look at a hypothetical financial services industry as a whole, and found that it contained 6 main firms with 15% market share apiece, then the industry would look non-monopolistic. However, one of those firms handles 90% of the checking and savings accounts and physical branches (and overcharges for them because of its monopoly), and the others primarily do commercial banking and investments. In this scenario, people would be suffering due to a market dominance by one firm; the market is not properly defined because checking accounts are not substitutable with commercial and investment banking. The problems of defining a market work the other way as well. To take another example, one cinema may have 90% of the movie market, but if movie theatres compete against video stores, pubs and nightclubs then people are less likely to be suffering due to market dominance.

- Another typical problem in defining the market is choosing a geographic scope. For example, firms may have 20% market share each, but may occupy five areas of the country in which they are monopoly providers and thus do not compete against each other. A service provider or manufacturer in one city is not necessarily substitutable with a service provider or manufacturer in another city, depending on the importance of being local for the business—for example, telemarketing services are rather global in scope, while shoe repair services are local.

The United States Federal anti-trust authorities such as the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission use the Herfindahl index as a screening tool to determine whether a proposed merger is likely to raise antitrust concerns. Increases of over 0.01 generally provoke scrutiny, although this varies from case to case. The Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice considers Herfindahl indices between 0.15 and 0.25 to be "moderately concentrated" and indices above 0.25 to be "highly concentrated".[6] As the market concentration increases, competition and efficiency decrease and the chances of collusion and monopoly increase.

Intuition

When all the firms in an industry have equal market shares, H = 1/N. The Herfindahl is correlated with the number of firms in an industry because its lower bound when there are N firms is 1/N. An industry with 3 firms cannot have a lower Herfindahl than an industry with 20 firms when firms have equal market shares. But as market shares of the 20-firm industry diverge from equality the Herfindahl can exceed that of the equal-market-share 3-firm industry (e.g., if one firm has 81% of the market and the remaining 19 have 1% each H=0.658). A higher Herfindahl signifies a less competitive industry.

The Herfindahl index is also a widely used metrics for economic concentration.[7] In portfolio theory, the Herfindahl index is related to the effective number of positions held in a portfolio. More precisely, this number is Neff = 1/H,[8] where H is computed as the sum of the squares of the proportion of market value invested in each security. A low H-index implies a very diversified portfolio: as an example, a portfolio with H = 0.01 is equivalent to a portfolio with Neff=100 equally weighted positions. The H-index has been shown to be one of the most efficient measures of portfolio diversification.[9]

Decomposition

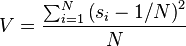

If we suppose that N firms share all the market, then the index can be expressed as  where N is the number of firms, as above, and V is the statistical variance of the firm shares, defined as

where N is the number of firms, as above, and V is the statistical variance of the firm shares, defined as  . If all firms have equal (identical) shares (that is, if the market structure is completely symmetric, in which case si = 1/N for all i) then V is zero and H equals 1/N. If the number of firms in the market is held constant, then a higher variance due to a higher level of asymmetry between firms' shares (that is, a higher share dispersion) will result in a higher index value. See Brown and Warren-Boulton (1988), also see Warren-Boulton (1990).

. If all firms have equal (identical) shares (that is, if the market structure is completely symmetric, in which case si = 1/N for all i) then V is zero and H equals 1/N. If the number of firms in the market is held constant, then a higher variance due to a higher level of asymmetry between firms' shares (that is, a higher share dispersion) will result in a higher index value. See Brown and Warren-Boulton (1988), also see Warren-Boulton (1990).

See also

- Microeconomics

- N50 statistic - a measure of concentration used in genomics

- Small but significant and non-transitory increase in price - a test to determine the relevant market

References

- 1 2 2010 Merger Guidelines § 5.3

- ↑ Catherine Liston-Hayes, Alan Pilkington, “Inventive Concentration: An Analysis of Fuel Cell Patents,” Science and Public Policy, (2004). Vol. 31, No. 1, p.15-25.

- ↑ Chapter 9 Organizing Production

- ↑ However, it gets far more complicated than that. See para. 16-21 Guidelines on horizontal mergers

- ↑ "Horizontal Merger Guidelines (08/19/2010)".

- ↑ "Herfindahl–Hirschman Index". USDOJ. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Lovett, William (1988). Banking and Financial Institutions Law in a Nutshell. West Publishing Co.

- ↑ Bouchaud, Jean-Philippe; Potters, Aguilar (1997). "Missing Information and Asset Allocation" (PDF).

- ↑ Woerheide, Walt; Persson, Don (1993). FINANCIAL SERVICES REVIEW 2 (2): 73–85. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Further reading

- Brown, Donald M.; Warren-Boulton, Frederick R. (May 11, 1988). "Testing the Structure-Competition Relationship on Cross-Sectional Firm Data". Discussion paper 88-6. Economic Analysis Group, U.S. Department of Justice.

- Capozza, Dennis R.; Lee, Sohan (1996). "Portfolio Characteristics and Net Asset Values in REITs". The Canadian Journal of Economics (Blackwell Publishing) 29 (Special Issue: Part 2): S520–S526. doi:10.2307/136100. JSTOR 136100.

- Hirschman, Albert O. (1964). "The Paternity of an Index". The American Economic Review (American Economic Association) 54 (5): 761. JSTOR 1818582.

- Kwoka, John E., Jr. (1977). "Large Firm Dominance and Price-Cost Margins in Manufacturing Industries". Southern Economic Journal (Southern Economic Association) 44 (1): 183–189. doi:10.2307/1057315. JSTOR 1057315.

- Warren-Boulton, Frederick R. (1990). "Implications of U.S. Experience with Horizontal Mergers and Takeovers for Canadian Competition Policy". In Mathewson, G. Franklin et al. (eds.). The Law and Economics of Competition Policy. Vancouver, B.C.: The Fraser Institute. ISBN 0-88975-121-8.

External links

- World Integrated Trade Solution, Calculate Herfindahl-Hirschman Index using UNSD COMTRADE data

- US Department of Justice example and market concentration cutoffs.

- Herfindahl-Hirschman Index Calculator. Web tool for calculating pre- and post-merger Herfindahl index.

- Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines. More detailed information about mergers, market concentration, and competition (from the Department of Justice).