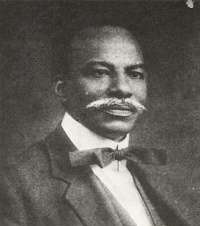

Herbert Macaulay

| Herbert Macaulay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Olayinka Badmus Macaulay November 14, 1864 Lagos, Nigeria |

| Died |

May 7, 1946 (aged 81) Lagos, Nigeria |

| Resting place | Ikoyi Cemetery |

| Residence | Lagos, Nigeria |

| Nationality | Nigerian |

| Ethnicity | Yoruba |

| Citizenship | Nigeria |

| Education |

Church Missionary Society Grammar School, Lagos Plymouth, England |

| Occupation | politician, engineer, architect, journalist, musician. |

| Years active | 1891 - 1946 |

| Known for | Nigerian nationalism |

| Political party |

Nigerian National Democratic Party National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons |

| Religion | Christianity |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Children |

Sarah Abigail Idowu Macaulay (daughter) Oliver Ogedengbe Macaulay (son) |

| Parent(s) |

Thomas Babington Macaulay (father) Abigail Crowther (mother) |

| Relatives |

Ojo Oriare (paternal grandfather) Samuel Ajayi Crowther (maternal grandfather) Julius Gordon Kwasi Adadevoh (son-in-law) Babatunde Kwaku Adadevoh (grandson) Modupe Smith (granddaughter) Joseph Chike Edozien (grandson-in-law) Ameyo Adadevoh (great-granddaughter) Bankole Cardoso (great-great-grandson) |

Olayinka Herbert Samuel Heelas Badmus Macaulay (14 November 1864 – 7 May 1946) was a Nigerian nationalist, politician, engineer, architect, journalist, and musician and is considered by many Nigerians as the founder of Nigerian nationalism.[1]

Early life

Olayinka Macaulay Badmus was born in Lagos on 14 November 1864 to Thomas Babington Macaulay and Abigail Crowther, children of people captured from what is now present day Nigeria, resettled in Sierra Leone by the British West Africa Squadron, and eventual returnees to present day Nigeria.[2] Thomas Babington Macaulay was one of the sons of Ojo Oriare while Abigail Crowther was the daughter of Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther, a descendant of King Abiodun.[2] Thomas Babington Macaulay was the founder of the first secondary school in Nigeria, the CMS Grammar School, Lagos.[3][4] After going to a Christian missionary school, he took a job as a clerk at the Lagos Department of Public Works. From 1891 to 1894 he studied civil engineering in Plymouth, England. On his return, he worked for the Crown as a land inspector. He was also the first Nigerian to own a motor car.[5][6][7] He left his position as land inspector in 1898 due to growing distaste for the British rule over the Lagos Colony and the position of Yorubaland and the Niger Coast Protectorate as British colonies in all but name.[5]

As an opponent of British rule

Herbert Macaulay was an unlikely champion of the masses. A grandson of Ajayi Crowther, the first African bishop of the Niger Territory, he was born into a Lagos that was divided politically into groups arranged in a convenient pecking order – the British rulers who lived in the posh Marina district, the Saros and other slave descendants who lived to the west, and the Brazilians who lived behind the whites in the Portuguese Town. Behind all three lived the real Lagosians, the masses of indigenous Yoruba people, disliked and generally ignored by their privileged neighbours. It was not until Macaulay’s generation that the Saros and Brazilians even began to contemplate making common cause with the masses.

Macaulay was one of the first Nigerian nationalists and for most of his life a strong opponent of British rule in Nigeria. As a reaction to claims by the British that they were governing with "the true interests of the natives at heart", he wrote: "The dimensions of "the true interests of the natives at heart" are algebraically equal to the length, breadth and depth of the whiteman's pocket." In 1908 he exposed European corruption in the handling of railway finances and in 1919 he argued successfully for the chiefs whose land had been taken by the British in front of the Privy Council in London. As a result, the colonial government was forced to pay compensation to the chiefs. In retaliation for this and other activities of his, Macaulay was jailed twice by the British. [4]

Macaulay became very popular and on 24 June 1923 he founded the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), the first Nigerian political party.[1] The party won all the seats in the elections of 1923, 1928 and 1933.[8][5]

As a supporter of the British

In 1931 relations between Macaulay and the British began to improve up to the point that the governor even held conferences with Macaulay.[8] In October 1938 the more radical Nigerian Youth Movement fought and won elections for the Lagos Town Council, ending the dominance of Macaulay and his National Democratic Party.[9]

Towards the end

In 1944 Macaulay co-founded the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) together with Nnamdi Azikiwe and became its president.[10] The NCNC was a patriotic organization designed to bring together Nigerians of all stripes to demand independence.[11] In 1946 Macaulay fell ill in Kano and later died in Lagos. The leadership of the NCNC went to Azikiwe, who later became the first president of Nigeria. Macaulay was buried at Ikoyi Cemetery in Lagos on 11 May 1946. Nnamdi Azikiwe delivered a funeral oration at Macaulay's burial ceremony.[12][5]

References

- 1 2 Saheed Aderinto (2015). Children and Childhood in Colonial Nigerian Histories. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 27. ISBN 9781137492937.

- 1 2 "Macaulay, Thomas Babington 1826 to 1878 Anglican Nigeria". Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Robert W. July (2004). The Origins of Modern African Thought: Its Development in West Africa During the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Africa World Press. p. 377. ISBN 9781592211999.

- 1 2 Webster et al. 1980, p. 266.

- 1 2 3 4 Isaac B. Thomas (1946). Life History of Herbert Macaulay, C. E. Tika-To[r]e Press.

- ↑ Daniel H. Ocheja (2001). The rise and fall of the Nigerian First Republic: history of Nigeria from Lord Lugard to Gen. Aguyi-Ironsi (1900-1966). Ogun De-Reuben (Nig.).

- ↑ "Herbert Macaulay" 43 (17-25). Newswatch Communications Limited. 2006.

- 1 2 Webster et al. 1980, p. 267.

- ↑ Coleman 1971, p. 225.

- ↑ Richard L. Sklar. Nigerian Political Parties: Power in an Emergent African Nation. Africa World Press. p. 61. ISBN 9781592212095.

- ↑ Webster et al. 1980, p. 299.

- ↑ Zik: A Selection from The Speeches of Nnamdi Azikiwe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9780521091350. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

Sources

- Coleman, James S. (1971). Nigeria: Background to Nationalism. University of California Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-520-02070-7.

- Webster, James Bertin; Boahen, A. Adu; Tidy, Michael (1980). The Revolutionary Years: West Africa since 1800. Longman. ISBN 0-582-60332-3.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|