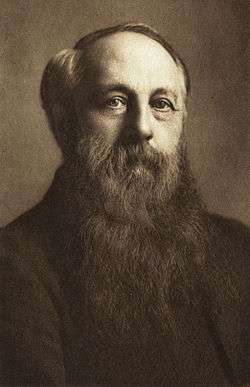

Henry Hyndman

Henry Mayers Hyndman (/ˈhaɪndmən/; 7 March 1842 – 20 November 1921) was an English writer and politician, and the founder of the Social Democratic Federation and the National Socialist Party.

Early years

The son of a wealthy businessman, Hyndman was born 7 March 1842 in London. After being educated at home, he entered Trinity College, Cambridge.[1] Hyndman later recalled:

"I had the ordinary education of a well-to-do boy and young man. I read mathematics hard until I went to Cambridge, where I ought, of course, to have read them harder, and then I gave them up altogether and devoted myself to amusement and general literature.... Trinity or, for that matter, any other college, is practically a hot-bed of reaction from the social point of view. The young men regard all who are not technically 'gentlemen' as 'cads,' just as the Athenians counted all who were not Greeks as barbarians."

"I was a thorough-going Radical and Republican in those days — theoretically ... with a great admiration for John Stuart Mill, and later, I remember, I regarded John Morley as the coming man."[2]

After achieving his degree in 1865 he studied law for two years before deciding to become a journalist.

As a first-class cricketer, he represented Cambridge University, MCC and Sussex in thirteen matches as a right-handed batsman between 1864 and 1865.

In 1866 Hyndman reported on the Italian war with Austria for the Pall Mall Gazette. Hyndman was horrified by the reality of war and became violently ill after visiting the front line. Hyndman met the leaders of the Italian nationalist movement and was generally sympathetic to their cause.

In 1869 Hyndman toured the world, visiting the United States, Australia and several European countries. He continued to write for the Pall Mall Gazette, where he praised the merits of British imperialism and criticised those advocating Home Rule for Ireland. Hyndman was also very hostile to the experiments in democracy that were taking place in the United States.

Political career

Hyndman decided on a career in politics, but, unable to find a party that he could fully support, he decided to stand as an Independent for the constituency of Marylebone in the 1880 General Election. Denounced as a Tory by William Ewart Gladstone, Hyndman got very little support from the electorate and, facing certain defeat, withdrew from the contest.

Soon after the election, Hyndman read a novel based on the life of Ferdinand Lassalle. He became fascinated with Lassalle and decided to research this romantic hero who had been killed in a duel in 1864. Discovering that Lassalle had been a socialist, sometimes a friend and sometimes an adversary of Karl Marx, Hyndman read The Communist Manifesto and, although he had doubts about some of Marx's ideas, was greatly impressed by his analysis of capitalism.

Hyndman was also greatly influenced by the book Progress and Poverty and the ideology of Henry George known today as Georgism.[3]

Hyndman then decided to form Britain's first socialist political party. The Democratic Federation had its first meeting on 7 June 1881. Many socialists were concerned that in the past Hyndman had been opposed to socialist ideas, but Hyndman persuaded many that he had genuinely changed his views, and those who eventually joined the SDF included William Morris and Karl Marx's daughter, Eleanor Marx. However, Friedrich Engels, Marx's long-term collaborator, refused to support Hyndman's venture.

Hyndman wrote the first popularisation of the ideas of Karl Marx in the English language, England for All in 1881. The book was extremely successful, a fact that stoked Marx's antipathy given the fact that he had failed to credit Marx by name in the introduction. The work was followed in 1883 by Socialism Made Plain, which expounded the policies of what by then had been renamed as the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). They included a demand for universal suffrage and the nationalisation of the means of production and distribution. The SDF also published Justice, edited by the talented journalist Henry Hyde Champion.

Although Hyndman was a talented writer and public speaker, many members of the SDF questioned his leadership qualities. He was extremely authoritarian and tried to restrict internal debate about party policy. At an SDF meeting on 27 December 1884, the executive voted, by a majority of two (10–8), that it had no confidence in Hyndman. When he refused to resign, some members, including William Morris and Eleanor Marx, left the party.

In the 1885 general election, Hyndman and Henry Hyde Champion, without consulting their colleagues, accepted £340 from the Tories to run parliamentary candidates in Hampstead and Kensington, the objective being to split the Liberal vote and therefore enable the Conservative candidate to win. This ploy failed, and the two SDF's candidates won only a total of 59 votes. The story leaked out, and the political reputation of both men suffered because they had accepted "Tory gold".

During the 1880s, he was a prominent member of the Irish National Land League and the Land League of Great Britain. He took part in the unemployed demonstrations of 1887 and was put on trial for his share in the Trafalgar Square riot, but was acquitted.[4]

He was chairman at the International Socialist Congress held in London in 1896. He was pro-Boer during the second Boer War.[5]

Hyndman continued to lead the SDF and took part in the negotiations to establish the Labour Representation Committee in 1900. However, the SDF left the LRC when it became clear that it was deviating from the objectives he had set out, and in 1911 he set up the British Socialist Party (BSP) when the SDF fused with a number of branches of the Independent Labour Party.

After the war

Hyndman upset members of the BSP by supporting the United Kingdom's involvement in World War I. The party split in two with Hyndman forming a new National Socialist Party. Hyndman remained leader of the small party until his death on 20 November 1921.

Bibliography

- A Commune for London (1888)

- Commercial Crisis of the Nineteenth Century (1892)

- Economics of Socialism (1890)

- The Awakening of Asia (1919)

- The Evolution of Revolution (1921)

References

- ↑ "Hyndman, Henry Mayers (HNDN861HM)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ H. Quelch, "H.M. Hyndman: An Interview," The Comrade, (New York), February 1902, pg. 114.

- ↑ Kohl, Norbert (2011). Oscar Wilde : the works of a conformist rebel. 1st pbk. ed.Cambridge England New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521176530.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Hyndman, Henry Mayers". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Hyndman, Henry Mayers". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York. - ↑

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Hyndman, Henry Mayers". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Hyndman, Henry Mayers". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henry Hyndman |

- Cricket Archive

- Henry Hyndman Internet Archive, Marxists Internet Archive.

- H. M. Hyndman, Commercial Crises of the Nineteenth Century (1892)

| Media offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by C. L. Fitzgerald |

Editor of Justice 1884–1886 |

Succeeded by Harry Quelch |

| Preceded by Harry Quelch |

Editor of Justice 1889–1891 |

Succeeded by Harry Quelch |

|