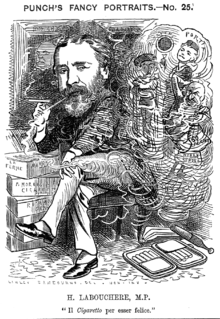

Henry Labouchère

- "Henry Labouchere" redirects here. For his uncle, see Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton

Henry Du Pré Labouchère (9 November 1831 – 15 January 1912) was an English politician, writer, publisher and theatre owner in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. He lived with the actress Henrietta Hodson from 1868, and they married in 1887.[1]

Labouchère, who inherited a large fortune, engaged in a number of occupations. He was a junior member of the British diplomatic service, a member of parliament in the 1860s and again from 1880 to 1906, and edited and funded his own magazine, Truth. He is remembered for the Labouchère Amendment to British law, which for the first time made all male homosexual activity a crime.

Unable to secure the senior positions to which he thought himself suitable, Labouchère left Britain and retired to Italy.

Life and career

Labouchère was born in London to a family of Huguenot extraction. His father, John Peter Labouchère (d. 1863), a banker, was the second son of French parents who had settled in Britain in 1816.[2] His mother, Mary Louisa née Du Pré (1799–1863) was from an English family.[3] Labouchère was the eldest of their three sons and six daughters.[4] He was the nephew of the Whig politician Henry Labouchere, 1st Baron Taunton, who, despite disapproving of his rebellious nephew, helped the young man's early career and left him a sizeable inheritance when he died leaving no male heir.[5]

Early career

Labouchère was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge,[6] where, he later said, he "diligently attended the racecourse at Newmarket," losing £6,000 in gambling in two years.[7] He was accused of cheating in an examination and his degree was withheld.[8] He left Cambridge and went travelling in Europe, South America and the United States.[9] While he was in the US, Labouchère (without his prior knowledge) was found a place in the British diplomatic service by his family. Between 1854 and 1864, Labouchère served as a minor diplomat in Washington, Munich, Stockholm, Frankfurt, St. Petersburg, Dresden, and Constantinople. He was, however, not known for his diplomatic demeanour, and acted impudently on occasion.[5] He went too far when he wrote to the Foreign Secretary to refuse a posting offered to him, "I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your Lordship's despatch, informing me of my promotion as Second Secretary to Her Majesty's Legation at Buenos Ayres. I beg to state that, if residing at Baden-Baden I can fulfil those duties, I shall be pleased to accept the appointment." He was politely told that there was no further use for his services.[10]

The year after his dismissal, Labouchère was elected at the 1865 general election as a member of parliament (MP) for Windsor,[11] as a Liberal. However, that election was overturned on petition,[5] and in April 1867 he was elected at a by-election as an MP for Middlesex.[12] At the 1868 election he narrowly lost his seat, winning only 90 votes less than his Conservative opponent's total of 6,487.[13] Labouchère did not return to the House of Commons for 12 years.[5]

In 1867, Labouchère and his partners engaged the architect C. J. Phipps and the artists Albert Moore and Telbin to remodel the large St. Martins Hall to create Queen's Theatre, Long Acre.[14] A new company of players was formed, including Charles Wyndham, Henry Irving, J. L. Toole, Ellen Terry, and Henrietta Hodson. By 1868, Hodson and Labouchère were living together out of wedlock,[15] as they could not marry until her first husband died in 1887.[16] Labouchère bought out his partners and used the theatre to promote Hodson's talents;[17] the theatre made a loss, Hodson retired, and the theatre closed in 1879. The couple finally married in 1887.[1] Their one child together, Mary Dorothea (Dora) Labouchère, had been born in 1884 and later was a daughter-in-law of Emanuele Ruspoli, 1st Prince of Poggio Suasa. Hodson's cousin was the theatre producer George Musgrove.[18]

Journalist and writer; 1879 altercation

During the break in his Parliamentary career, Labouchère gained renown as a journalist, editor, and publisher, sending witty dispatches from Paris during the siege in 1870. His unflinching style gained a large audience for first his reporting, and later his personal weekly journal, Truth (started in 1877), which was often sued for libel.[19] With his inherited wealth, he could afford to defend such suits.[5] Labouchère's claims to being impartial were ridiculed by his critics, including W. S. Gilbert (who had been an object of Labouchère's theatrical criticism) in Gilbert's comic opera His Excellency (see illustration at right). In 1877, Gilbert had engaged in a public feud with Labouchère's lover, Henrietta Hodson.[20]

Labouchère was a vehement opponent of feminism; he campaigned in Truth against the suffrage movement, ridiculing and belittling women who sought the right to vote.[21] He was also a virulent anti-semite, opposed to Jewish participation in British life, using Truth to campaign against "Hebrew barons" and their supposedly excessive influence, "Jewish exclusivity" and "Jewish cowardice".[21] One of the victims of his attacks was Edward Levy-Lawson, proprietor of The Daily Telegraph.[21] In 1879 there was a much-reported court case following a fracas on the doorstep of the Beefsteak Club between Labouchère and Levy-Lawson. The committee of the club expelled Labouchère, who successfully sought a court ruling that they had no right to do so.[22]

Return to Parliament

Labouchère returned to Parliament in the 1880 election, when he and Charles Bradlaugh, both Liberals, won the two seats for Northampton. (Bradlaugh's then-controversial atheism led Labouchère, a closet agnostic, to refer sardonically to himself as "the Christian member for Northampton".)[5]

In 1884, Labouchère unsuccessfully proposed legislation to extend the existing laws against cruelty to animals.[23] In 1885, Labouchère, whose libertarian stances did not preclude a fierce homophobia,[5] drafted the Labouchère Amendment as a last-minute addition to a Parliamentary Bill that had nothing to do with homosexuality.[n 1] His amendment outlawed "gross indecency"; sodomy was already a crime, but Labouchère's Amendment now criminalised any sexual activity between men.[n 2] Ten years later the Labouchère Amendment allowed for the prosecution of Oscar Wilde, who was given the maximum sentence of two years' imprisonment with hard labour.[5] Labouchère expressed regret that Wilde's sentence was so short, and would have preferred the seven-year term he had originally proposed in the Amendment.[5]

During the 1880s, the Liberal Party faced a split between a Radical wing (led by Joseph Chamberlain) and a Whig wing (led by the Marquess of Hartington), with its party leader, William Ewart Gladstone straddling the middle. Labouchère was a firm and vocal Radical, who tried to create a governing coalition between the Radicals and the Irish Nationalists that would exclude or marginalise the Whigs. This plan was wrecked in 1886, when, after Gladstone came out for Home Rule, a large contingent of both Radicals and Whigs chose to leave the Liberal Party to form a "Unionist" party allied with the Conservatives.[5]

Between 1886 and 1892, a Conservative government was in power, and Labouchère worked tirelessly to remove them from office. When the government was turned out in 1892, and Gladstone was called to form an administration, Labouchère expected to be rewarded with a cabinet post. Queen Victoria refused to allow Gladstone to offer Labouchère an office, however (he had insulted the Royal Family). According to the historian Vernon Bogdanor, this was the last time a British monarch vetoed a prime minister's appointment of a cabinet minister.[28][n 3] Likewise, the new foreign secretary, Lord Rosebery, a personal enemy of Labouchère, declined to offer him the ambassadorship to Washington for which Labouchère had asked.[5]

In 1897, Labouchère was accused in the press of share-rigging, using Truth to disparage companies, advising shareholders to dispose of their shares and, when the share prices fell as a result, buying them himself at a low price. When he failed to reply to the accusations, his reputation suffered accordingly.[31] After being snubbed for a second time by the Liberal leadership after their victory in the 1906 election, Labouchère resigned his seat and retired to Florence. He died there seven years later, leaving a fortune of some two million pounds sterling to his daughter Dora, who was by then married to Carlo, Marchese di Rudini.[5]

Notes and references

- Notes

- ↑ The Criminal Law Amendment Bill, 1885 was introduced to outlaw sex between men and underage girls.[24]

- ↑ Labouchère's contemporary Frank Harris wrote that Labouchère proposed the amendment to make the law seem "ridiculous" and so discredit it in its entirety; some historians agree, citing Labouchère's habitual obstructionism and other attempts to sink this bill by the same means. Others write that Labouchère's role in the Cleveland Street scandal makes it plain that he was strongly in favour of using the criminal law to control male sexuality, despite his own irregular private life.[25][26][27]

- ↑ Francis Beckett (quoting from the diaries of Sir Alan Lascelles) claims otherwise, suggesting that George VI vetoed the appointment of Hugh Dalton as foreign secretary by Clement Attlee in 1945.[29] Roy Jenkins, however, notes that Attlee ignored the king's advice, which was given on 26 July 1945, and offered the foreign secretaryship to Dalton the following day, later changing his mind after receiving representations from Herbert Morrison and senior civil servants.[30]

- References

- 1 2 "Henry Du Pre Labouchere", The Twickenham Museum, accessed 3 March 2014

- ↑ Thorold, p. 13

- ↑ Thorold, p. 16

- ↑ Booth, Michael R. "Terry, Dame Ellen Alice (1847–1928)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition, January 2008, accessed 4 January 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sidebotham, Herbert, H. C. G. Matthew. "Labouchere, Henry Du Pré (1831–1912)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2009 accessed 26 May 2011 (subscription required)

- ↑ "Labouchere, Henry Dupré (LBCR850HD)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Thorold, p. 22

- ↑ Thorold, p. 26

- ↑ Thorold, pp. 38–45

- ↑ Thorold, p. 65

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 22991. p. 3529. 14 July 1865. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 23242. p. 2310. 16 April 1867. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ Craig, F. W. S. (1989) [1977]. British parliamentary election results 1832–1885 (2nd ed.). Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services. ISBN 0-900178-26-4.

- ↑ Sherson, p. 201

- ↑ Labby and Dora (Labouchere genealogy site) accessed 1 April 2008

- ↑ London Facts and Gossip 17 January 1883 The New York Times accessed 1 April 2008

- ↑ Feature on Hodson in Footlights Notes

- ↑ Gittins, Jean. "Musgrove, George (1854–1916)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1974, accessed 26 May 2011

- ↑ The Times, 31 December 1957, p. 6

- ↑ Vorder Bruegge, Andrew (Winthrop University). "W. S. Gilbert: Antiquarian Authenticity and Artistic Autocracy" . Paper presented at the Victorian Interdisciplinary Studies Association of the Western United States annual conference in October 2002, accessed 26 March 2008

- 1 2 3 Hirshfield, Claire. "Labouchere, Truth and the Uses of Antisemitism", Victorian Periodicals Review, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Fall, 1993), pp. 134–142

- ↑ "High Court of Justice, Nov. 28, Chancery Division", The Times, 29 November 1879, p. 4

- ↑ "Cruelty to Animals Acts Extension Bill", Hansard, 7 February 1884

- ↑ Text of the 1885 Act, accessed 7 March 2012

- ↑ Kaplan, Morris B. (2005). Sodom on the Thames: sex, love, and scandal in Wilde times. Cornell University Press. p. 175.

- ↑ Aldrich, Robert; Wotherspoon, Garry, eds. (2003). Who's who in gay and lesbian history: from antiquity to World War II. Psychology Press. p. 298.

- ↑ Cohen, Ed (1993). Talk on the Wilde side: toward a genealogy of a discourse on male sexualities. Psychology Press. p. 92.

- ↑ Bogdanor, p. 34

- ↑ Beckett, p. 199

- ↑ Jenkins, pp. 447–448

- ↑ "The stock-jobbing of Henry Labouchere" LSE Selected Pamphlets, 1897, accessed 28 May 2011 (subscription required)

Sources

- Beckett, Francis (2000). Clem Attlee. Politico's Publishing Limited. p. 199. ISBN 1-902301-70-6.

- Bogdanor, Vernon (1997). The Monarchy and the Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829334-8.

- Jenkins, Roy (1998). The Chancellors. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-73057-7.

- Sherson, Erroll (1925). London's Lost Theatres of the Nineteenth Century. London: Bodley Head. OCLC 51413815.

- Thorold, Algar (1913). The Life of Henry Labouchere. New York and London: G. P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 400277.

Further reading

- Russell, George W. E. (1916). Portraits of the Seventies. London: Fisher Unwin. OCLC 221085405.

- "Henry Du Pre Labouchere". The Twickenham Museum.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Labouchère. |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Henry Labouchère

- Works by Henry Labouchere at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Labouchère at Internet Archive

- "The Brown Man's Burden" (1899), a parody by Labouchère of Rudyard Kipling's "The White Man's Burden"; published in Truth, a London journal

- Henry Labouchère materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Richard Vyse William Vansittart |

Member of Parliament for Windsor 1865 – 1866 With: Sir Henry Hoare, Bt |

Succeeded by Charles Edwards Roger Eykyn |

| Preceded by Robert Culling Hanbury George Byng |

Member of Parliament for Middlesex 1867 – 1868 With: George Byng |

Succeeded by Lord George Hamilton George Byng |

| Preceded by Pickering Phipps Charles George Merewether |

Member of Parliament for Northampton 1880 – 1906 With: Charles Bradlaugh 1880–1891 Moses Manfield 1891–1895 Charles Drucker 1895–1900 John Greenwood Shipman from 1900 |

Succeeded by Herbert Paul John Greenwood Shipman |

|