Henry Ince

Henry Ince (1736–1808) was a sergeant-major (and later lieutenant) in the British Army who achieved fame as the author of a plan to tunnel through the North Face of the Rock of Gibraltar in 1782, during the Great Siege of Gibraltar. As a result of his work, by the end of the 18th century Gibraltar had almost 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of tunnels in which dozens of cannons were mounted overlooking the isthmus linking the peninsula to Spain. He was one of the first members of the Soldier Artificer Company, a predecessor to today's Royal Engineers, and rose to be the Company's senior non-commissioned officer. He was also a founder of Methodism in Gibraltar through his activities as a Methodist lay preacher. Ince spent most of his life in the Army and served for 36 years in Gibraltar before retiring to Devon four years before he died at the age of 72.

Early life and posting to Gibraltar

Born in Penzance in Cornwall in 1736, Ince first worked as a nailor (a nail-maker) before turning his hand to mining. He enlisted in the 2nd (The Queen's Royal) Regiment of Foot in 1755 and served in Galway, Ireland. The Regiment remained in Ireland until June 1765, when it was posted to the Isle of Man. It was subsequently sent to Gibraltar in March 1768, where Ince was able to put his mining skills to use.[1][2]

He was also a highly active Methodist lay preacher, and may have met John Wesley during the latter's preaching in Ireland between 1756–65. Although no record of such a meeting has survived, Wesley's journal records that he often preached to soldiers in Irish towns where Ince's regiment happened to be stationed at the time. On 3 April 1769 Ince wrote to Wesley from Gibraltar in terms which suggest that the two men did know each other:[1]

At our first coming to this place, I found a people of such abominable practices, as I never before had seen. However, I and two or three more took a room to meet in, and we were soon joined by some of the Royal Scotch: but this continued only a short time; the reason was, they would not allow your hymns to be sung, neither your works to be read. Upon this I was obliged to declare, that while I could get any of your writings to make use of, I would use them; since I had found them agreeable to the word of God. And as God gave me a word to speak, I cared not who heard, so He might be glorified. On this many were offended, and separated from us.Yet, in about two months, we were thirty-seven in number, till a little persecution came, then we were reduced to about eighteen. But, blessed be God! he is reviving his work again. We are now thirty-two, fifteen of whom can rejoice in the pardoning love of God, and most of the others are pressing hard after it. Several Officers come to hear, and God gives favour in the sight of all men. There is one Gentleman of the town who has joined us lately, and is a very great help to us.

As to myself, God is ever gracious to me, who am less than the least of his children. I am astonished that he should work by me! O, that I may be found faithful unto death! and that he may carry on his work in this barren place! So prays your unworthy Friend, Henry Ince.[1]

Ince's comments indicate that the Methodists of Gibraltar were initially ill-treated by members of other denominations. This certainly seems to have been the case, as only a couple of months after Ince wrote his letter the Governor of Gibraltar, Lieutenant General Edward Cornwallis, issued an order that "no person whatever [shall] presume to molest them nor go into their meeting to behave indecently there."[3]

According to Gibraltarian Methodist tradition, the colony's first regular Methodist meeting place was Ince's old home on Prince Edward's Road – a claim which is made on a plaque that was originally mounted in the Methodist Church on Prince Edward's Road and is now in the modern Gibraltar Methodist Church on Main Street. However, there is no evidence to support this; according to Ince's own correspondence to Wesley, he hired a room in which the Methodists could meet, rather than using his own home, and the site on Prince Edward's Road where the first Methodist Church was built was leased to another man during Ince's lifetime. He is recorded as owning property elsewhere in Gibraltar, on the east side of Main Street.[4]

Service with the Soldier Artificer Company

On 26 June 1772, Ince joined the Army's first unit of military artificers and labourers, the Soldier Artificer Company, and was promoted to sergeant on the same day.[2] The Company was established by Lieutenant Colonel William Green to assist his programme of improvements to the fortifications of Gibraltar. He was posted to the fortress in 1761 as its Senior Engineer and in 1769 he put forward improvement plans which were eventually approved.[5] The works were initially carried out by civilians recruited from England and elsewhere in Europe, but this proved slow, expensive and unsatisfactory.[6] To resolve these problems, Green was authorised to raise a 68-man company consisting of one sergeant-adjutant, three sergeants, three corporals, one drummer and 60 privates working variously as stonecutters, masons, miners, lime-burners, carpenters, smiths, gardeners and wheel-makers.[7]

Ince was one of the first two sergeants mustered into the Company on 30 June 1772.[8] Seven years later, the Great Siege began as a French and Spanish army laid siege to Gibraltar in what was to become the longest siege ever endured by a British garrison. The members of the Company carried out extensive work on the fortifications to repair damage caused by enemy bombardments and strengthen Gibraltar's defences.[9] They also participated in a highly successful sortie against the Spanish lines on 27 November 1781, though it is not known whether Ince himself participated. This led to them being praised in dispatches by the new Governor, General George Eliott.[10][11]

Despite British counter-fire, the Spanish were able to advance slowly along the isthmus linking Gibraltar with Spain by extending their trenches towards the British lines. The closer they came, the more difficult it was for the British to aim their cannon down into the Spanish lines. The near-vertical cliff of the North Front of the Rock of Gibraltar greatly restricted the space in which the British cannon could be deployed.[12] By May 1782 the Spanish had been able to knock out many of the British batteries on the North Front without the British being able to return fire adequately.[13]

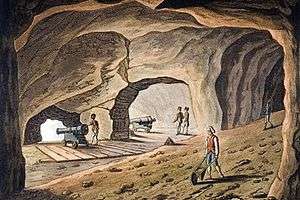

General Eliott offered a bounty of 1,000 Spanish dollars to "any one who can suggest how I am to get a flanking fire upon the enemy's works". In response, Henry Ince – who had been promoted to the rank of Sergeant-Major in September 1781 – proposed to tunnel a gallery through the Rock. It would start from a position above Farringdon's Battery to reach an outcrop called the Notch, so that a cannon could be mounted there to cover the entire North Front.[14] His suggestion was immediately approved and Colonel Green issued an order on 22 May 1782: "A gallery 6 feet high, and 6 feet wide, through the rock, leading towards the notch nearly under the Royal Battery, to communicate with a proposed battery to be established at the said notch, is immediately to be undertaken and commenced upon by 12 miners, under the executive direction of Sergeant-major Ince."[14]

Construction of the Gibraltar siege tunnels

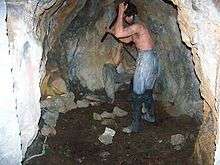

The task of excavating the tunnels began on 25 May 1782, carried out entirely by hand.[14] The miners broke up the limestone rock using a variety of methods, including gunpowder blasting, fire-setting (building a fire against the face of the rock to heat it, then quenching it with cold water to cause it to shatter), quicklime (used to fill boreholes which were then slaked with water, causing it to expand and so shattering the surrounding rock) and hammering in wooden wedges which were expanded by soaking them with water, again causing the rock to shatter. The fragments were then removed with crowbars and sledgehammers. Progress was slow, advancing at a rate of only about 200 metres (660 ft) per year, but the tunnels thus excavated have proved extremely stable and are still readily accessible today.[15]

The miners suffered from poor ventilation until the decision was taken to blast a small opening in the cliff face to provide them with a supply of fresh air. It was immediately realised that this would offer an excellent firing position. By the end of the siege, the newly created Upper Gallery housed four guns, mounted on specially developed "depressing carriages" to allow them to fire downwards into the Spanish positions. The Notch was not reached until after the siege had ended; instead of mounting a gun above it, the outcrop was hollowed out to create a broad firing position.[12]

It is unclear whether Ince actually received his thousand-dollar reward, but according to a story handed down by the descendants of soldiers who had served in the company, he received one guinea per running foot. This would have amounted to a substantial sum;[14] by the time the siege had ended in 1783, the Windsor Gallery leading to the Notch measured between 500 and 600 feet in length.[16] In his Journal of the Siege of Gibraltar, Captain John Spilsbury recorded: "Ince's gallery has 10 embrasures and an air hole cut, and is about 600 and odd feet long; the 9th chamber or cave is large enough for a guard room, has 2 doors, and is tolerably dry."[11] When the French general commanding the Franco-Spanish army, the Duc de Crillon,[17] visited the tunnels after a ceasefire had been declared, he is said to have exclaimed, "These works are worthy of the Romans."[16]

The tunnelling continued after the end of the siege under Ince's supervision and by 1799 the tunnels had reached a total length of nearly 4,000 feet (1,200 m).[18] They were constructed in two tiers, known as the Upper (or Windsor) and Lower (or Union) Galleries, mounting around 40 heavy cannon and with magazines and bombproof shelters constructed adjoining them.[16] The Upper Galleries are today a popular tourist attraction called the Great Siege Tunnels.[19]

Later career and death

In January 1787 Ince was granted a plot of ground on the Queen's Road, some distance up the Rock of Gibraltar, which is still called Ince's Farm. During the siege he had turned it into a small cultivated plot with the permission of the Governor.[20] The original grant still survives and states:

Whereas Henry Ince Sergeant Major in the Royal Military Artificer Company having at his own expense, during the late blockade and with my consent and permission for the improvement and benefit of the place, enclosed and cultivated a certain extent of ground situated on the center of the Hill above the town which ground the said Henry Ince hath partly planted with trees, erected some buildings thereon and otherwise improved and converted the same into kitchen garden for raising greens and other esculent plants and roots for market, that have ever since proved to be of great utility to the Garrison in General. Wherefor for the encouragement of so usefull an undertaking and the increase of vegetables, roots and fruits for the benefit and consumption of the Troops and Community, as well as the increase of the King's Revenue, I do, by virtue of the power and authority to me given by His Majesty hereby let and grant the said ground and appurtenances unto the same Henry Ince,.... for the space and term of forty one years.[21]

He was charged a rent of 12 reals a month for which he was required to fulfil certain conditions, including building a fence around the farm and planting as many lemon trees as possible.[21] The lease was renewed for a further 66 years in January 1803 "on account of his former and meritorious services." Perhaps appropriately, by the mid-20th century it had been turned into a store depot for the Soldier Artificers' successors, the Royal Engineers.[22]

Ince was discharged from the Company in 1791 but continued to work on the tunnels as "overseer of the mines", in charge of blasting, mining and battery construction. He was commissioned as an ensign on 2 February 1796. In March 1801 he was posted to the Channel Islands but the Governor intervened to prevent this and Ince was promoted to lieutenant on 24 March 1801.[23] He was described as "active, prompt, and persevering, very short in stature, but wiry and hardy in constitution; was greatly esteemed by his officers, and frequently the subject of commendation from the highest authorities at Gibraltar."[16]

According to one story, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn replaced Ince's worn-out nag with a fine new horse "more in keeping with your worth and your duties." However, the next time the Duke saw Ince, the latter was still riding his old horse. The Duke asked why, to which Ince replied that he was unable to manage such a spirited animal and asked if he could give the horse back. "No, no, overseer," the Duke is said to have replied; "if you can't ride him easily, put him into your pocket!" Ince grasped the Duke's meaning and sold the horse for a tidy sum of doubloons.[24]

Ince was married, though it is not known when or how many times. His wife's name is recorded variously as Jane in a baptismal record of August 1788, Joanna in another record of October 1792 and Fanny in his will of 8 August 1807, suggesting that he may have married at least twice. He may well have married before he came to Gibraltar, but this is unclear as the territory's marriage records do not start until 1771. The baptism of a son, Joseph Ince, is recorded on 5 February 1771 though no mother's name is given. Mrs Ince and a child are recorded as having left Gibraltar for England on 2 January 1782 aboard the Mercury, a transport ship. Another son, Robert, was baptised in Gibraltar in August 1788 and a second son, Henry, in October 1792. There were clearly other children whose births are not recorded; Thomas Ince, who worked as a clerk in the garrison's Commissariat, had three children baptised between 1795 and 1803 but died with his wife Eliza in the yellow fever epidemic of 1804. His eldest daughter Augusta married another lieutenant in the garrison.[24] In his will, Ince lists his surviving children as Joseph, William Boyd, Robert, Harriet, Henry and George.[25]

Ince returned to England in 1804 and died on 9 October 1808 in Gittisham, Devon.[26] His gravestone, which was later renovated by the Institution of Royal Engineers,[23] bears the inscription:

In Memory of Lieut HENRY INCE, late of the Royal Garrison Battn, Gibraltar, the works of which Fortress bear lasting testimony to his skill industry and zeal. After serving his Majesty 49 Years he retired full of honor to this place and closing in piety, the remains of a useful life, died October 9th, 1808, Aged 72. His principal service was in the Soldier Artificer Company, the first unit of the Corps of Royal Engineers.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 Jackson, pp. 17–18

- 1 2 Connolly, p. 29

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Hills, p. 308

- ↑ Connolly, p. 1

- ↑ Connolly, p. 3

- ↑ Connolly, p. 5

- ↑ Connolly, p. 10

- ↑ Connolly, pp. 12–13

- 1 2 Jackson, p. 21

- 1 2 Fa & Finlayson, p. 30

- ↑ Connolly, p. 13

- 1 2 3 4 Connolly, p. 14

- ↑ Rose, p. 255

- 1 2 3 4 Connolly, p. 27

- ↑ Courcelles, p. 295

- ↑ Hughes & Migos, p. 248

- ↑ Fa & Finlayson, p. 54

- ↑ Gilbard, p. 54

- 1 2 Jackson, p. 23

- ↑ Neame, p. 29

- 1 2 Jackson, p. 25

- 1 2 Connolly, p. 30

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 24–5

- ↑ "Great Siege Tunnels". Visit Gibraltar. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ↑ "Gravestone of Henry Ince". October 1808. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Connolly, Thomas William John (1855). The History of the Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners, Volume 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans.

- de Courcelles, Jean Baptiste Pierre Jullien (1820). Dictionnaire historique et biographique des généraux français. Paris: Arthus Bertrand.

- Fa, Darren; Finlayson, Clive (2006). The Fortifications of Gibraltar. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 1-84603016-1.

- Gilbard, George James (1888). A Popular History of Gibraltar, its Institutions, and its Neighbourhood on Both Sides of the Straits. Gibraltar: Garrison Library. OCLC 12225618.

- Hills, George (1974). Rock of Contention: A History of Gibraltar. London: Robert Hale & Company. p. 308. ISBN 0-7091-4352-4.

- Hughes, Quentin; Migos, Athanassios (1995). Strong as the Rock of Gibraltar. Gibraltar: Exchange Publications. OCLC 48491998.

- Jackson, Susan Irene (2000). "Methodism in Gibraltar and its mission in Spain, 1769–1842" (PDF). Durham University.

- Neame, Philip. Playing with Strife: The Autobiography of a Soldier. London: George G. Harrap. OCLC 1541023.

- Rose, Edward P.F. (2000). "Fortress Gibraltar". In Rose, Edward P.F.; Nathanail, C. Paul. Geology and Warfare: Examples of the Influence of Terrain and Geologists on Military Operations. Geological Society. ISBN 9781862390652.