Henry Barber (rock climber)

_-_5.jpg)

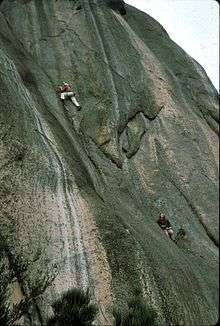

Henry Barber (born 1953 in Boston, Massachusetts) was a leading American rock climber and ice climber in the 1970s. Known by the nickname "Hot Henry", Barber was an advocate of clean climbing, a prolific first ascenscionist and free soloist. He was one of the first American rock climbers to travel widely to climb in different countries. Barber was one of the first "professional" American rock climbers, supporting himself as a sales representative for outdoor equipment companies including Chouinard Equipment and Patagonia, and by giving lectures and slide shows. He was an integral member of the "Front Four" quartet of the 1970s: "Hot Henry", John Stannard, Steve Wunsch, and John Bragg.

Initial climbs

At age 17, Barber started climbing with the Boston chapter of the Appalachian Mountain Club. Although initially not athletically gifted, he became obsessed with the sport, and persevered, climbing as much as possible. By his own account, Henry climbed approximately 270 days in 1972, and 325 in 1973.

In 1973, Henry did the second ascent of Foops, a 5.11 climbing route in the Gunks; this was five years after John Stannard had done the pioneering first ascent. In rock climbing, especially at popular crags like the Gunks, a second ascent is normally done soon after the first, usually in a matter of days or weeks.

Hot Henry

Barber was known for climbing in trademark white golfer's cap and white painter's pants, as well as his abrasive and arrogant demeanor. He was one of the few climbers of his era to actively seek and use media attention. His repertoire of moves, creativity, and problem-solving abilities, and his tremendous self-confidence and mental control, set him apart from his contemporaries.

Henry Barber was an early advocate of clean climbing, climbing with only nuts for protection. Henry was an active climber before the era of spring-loaded camming devices that made protecting cracks without pitons feasible. One of Barber's specialties was doing the first free ascent of established aid climbs.

Barber was a prolific soloist, specializing in on-sight solo ascents. In 1973, Barber soloed the Steck-Salathé Route on Sentinel Rock in Yosemite National Park. The solo ascent, done on-sight in 2½ hours, first brought Barber to prominence as a leading rock climber.[1]

International travel

In 1976 Henry (with Steve Wunsch and Fritz Wiessner) traveled to Dresden, East Germany as the first American climbing visitors. Wiessner had learned rock climbing around Dresden early in the century. Tradition (and soft, fragile sandstone) demanded that rock climbers use no metal for protection, relying instead only on knotted nylon slings jammed into cracks to hold a leader's fall. Climbers were expected to climb barefoot, and to abstain from the use of gymnasts' chalk. Barber was impressed with the rigours and difficulty of climbing around Dresden; the Dresden climbers were impressed with Henry's ability, although they also thought him too reckless, especially in the area of free soloing.

Barber was well-traveled at a time when rock climbers generally did not stray far from their home crags. His style was to show up at an area and greatly exceed local standards. In one trip he single-handedly jumped technical standards in Australia by more than a number grade. Other accomplishments include first ascent of the often-tried Butterballs in Yosemite; blazing a trail of desperate first ascents in the Gunks; and on-sight free-soloing dozens of routes on many different rock types in many different countries, up to hard 5.10, at a time when the 5.11 grade was only starting to solidify. Barber climbed at Mount Arapiles in Australia; Dresden; Great Britain; Scotland; Russia; Mexico; as well as climbing all over the United States, from the crags of New England to Yosemite in California, and (seemingly) most crags in between.

Ice climbing

In 1977, Barber travelled with Rob Taylor to Scotland and Norway to climb waterfalls. They did the (likely) first ascent of the Vettisfossen near Ardal, Norway (300m, WI5), among other climbs.[2]

In early 1978, Henry and partner Rob Taylor attempted the first ascent of the Breach Wall on Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Taylor fell while leading steep ice, and broke his ankle very badly. The details of what happened following the accident vary depending on which of the two parties is telling the story. Barber's party says that Barber helped Taylor descend; got him to a hospital; and then left to fly back to the United States to keep a speaking commitment. Taylor's party says that Barber abandoned him on the mountain, forcing him to climb down alone with his leg mangled. He somehow reached the rainforest at the base of the mountain and was rescued by local tribesman. Taylor nearly lost his leg at the hospital, and felt abandoned by his partner. After he recovered, Taylor wrote articles and a book (The Breach, Putnam, 1981) painting Barber in a very unflattering light.

This incident effectively ended Barber's career as a top climber. Barber continued to climb at a very high level after the Taylor incident, for example making the first free ascent of Women in Love (5.12), Cathedral Ledge, New Hampshire. Barber continues to travel worldwide, climbing in his own style and learning other's styles. He eschews modern camming devices and harnesses, preferring the simpler, more rigorous style of nuts and swami belt.

Barber currently lives near North Conway, New Hampshire. He still climbs, and presents climbing slide shows and lectures.

Bibliography

- Lee, Chip (1982). On Edge the life and climbs of Henry Barber. Boston, MA, USA: Appalachian Mountain Club. pp. 169–171. ISBN 0-910146-35-7.

- Waterman, Laura; Guy Waterman; S Peter Lewis (2002). Yankee Rock & Ice: A History of Climbing in the Northeastern United States. Mechanicsburg, PA, USA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3103-0.

- Williams, Richard (2005) Shawangunk Rock Climbs: The Trapps, esp. History

- Taylor, Rob (1981). The Breach: Kilimanjaro and the Conquest of Self. Putnam Pub Group. ISBN 0-698-11086-2.