William Gillette

| William Gillette | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

William Hooker Gillette July 24, 1853 Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died |

April 29, 1937 (aged 83) Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor, playwright, inventor, stage manager, |

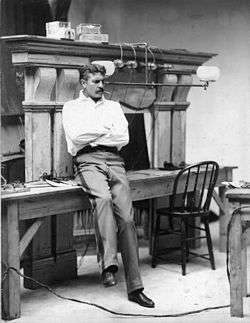

William Hooker Gillette (July 24, 1853 – April 29, 1937) was an American actor-manager, playwright, and stage-manager in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is best remembered for portraying Sherlock Holmes on stage and in a 1916 silent film long thought lost.

Gillette's most significant contributions to the theater were in devising realistic stage settings and special sound and lighting effects, and as an actor in putting forth what he called the "Illusion of the First Time". His portrayal of Holmes helped create the modern image of the detective. His use of the deerstalker cap (which first appeared in some Strand illustrations by Sidney Paget) and the curved pipe became enduring symbols of the character.[1] He assumed the role on stage more than 1,300 times over thirty years, starred in the silent motion picture based on his Holmes play, and voiced the character twice on radio.[2]

His first Civil War drama Held by the Enemy (1886) was a major step toward modern theater, in that it abandoned many of the crude devices of 19th century melodrama and introduced realism into the sets, costumes, props, and sound effects. It was produced at a time when the British had a very low opinion of American art in any form, and it was the first wholly American play with a wholly American theme to be a critical and commercial success on British stages.[3]

Youth

William Gillette was born in Nook Farm, Hartford, Connecticut, a literary and intellectual center with residents such as Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Charles Dudley Warner.[4]

Gillette's father Francis was a former United States Senator and a crusader public education, temperance, for the abolition of slavery, and women's suffrage.[5] His mother Elisabeth Daggett Hooker was a descendant of the Reverend Thomas Hooker, the Puritan leader who founded the town of Hartford and either wrote or inspired the first written constitution in history to form a government.[6] Gillette had three brothers and a sister. Another sister named Mary died as a small child.[7]

His eldest brother Frank Ashbell Gillette went to California and died there in 1859 from consumption (tuberculosis).[8] The third oldest brother Robert joined the Union Army and served in the Antietam campaign, was invalided home sick, recovered, and joined the Navy.[9] Robert Gillette was assigned to the U.S.S. Gettysburg and took part in both assaults on Fort Fisher. He was killed the morning after the surrender of the fort when the powder magazine exploded.[10] His brother Edward moved to Iowa and his sister Elisabeth married George Henry Warner, both in 1863, after which William was the only child in the household.

At the age of 20, he left Hartford to begin his apprenticeship as an actor. He briefly worked for a stock company in New Orleans and then returned to New England where, on Mark Twain's own recommendation, he debuted at the Globe Theater of Boston with Twain's stage-play The Gilded Age in 1875. Afterward, he was a stock actor for six years through Boston, New York, and the Midwest. He irregularly attended classes at a few institutions, although he never completed their programs. His father Francis had held the strongest objections to the theater in general, but he offered the least resistance and drove him to the train station, telling his son that he had driven two other sons to this same station and they had never returned; William was to make sure that he was the exception.[11] Francis supplied him with an allowance on which to subsist (his apprenticeship was without pay).[12]

His father's health began to fail in 1878, and William forsook the stage for more than a year to care for him in his final illness. Upon his father's death, he and George Henry Warner were named executors of Francis' estate, and they, Elisabeth, and Edward shared in the inheritance.[13]

Marriage

In 1882, Gillette married Helen Nichols of Detroit. She died in 1888 from peritonitis caused by a ruptured appendix.[14] He never remarried.

Playwright, director, actor

Gillette was hired as playwright, director, and actor for $50 per week in 1881, while performing at Cincinnati, by two of the Frohman brothers, Gustave and Daniel. The first play that he wrote and produced was The Professor. It debuted in the Madison Square Theatre, lasting 151 performances, with a subsequent tour through many states (as far west as St. Louis, Missouri). That same year, he produced Esmeralda, written together with Frances Hodgson Burnett.[15]

Early in his career, Gillette realised that it would be in the triple role of playwright, director, and actor that he could make the most money. He was among the premier matinee idols of his day, and was described by Amy Leslie as "one of Gibson's notables materialized".[16] Lewis Strang observed that "he rarely gesticulates, and his bodily movements often seem purposely slow and deliberate. His composure is absolute and his mental grasp of a situation is complete."[17]

He could mesmerize an audience simply by standing motionless and in complete silence, or by indulging in any one of his grand gestures or subtle mannerisms. He did not gesture often but, when he did, it meant everything. He would steal a scene with a mere nod, a shrug, a glance, a twitching of the fingers, a compression of his lips, or a hardening of his face. Slight inflections in his voice spoke wonders. "Occasionally", Georg Schuttler pointed out, "when it was least expected, he gestured or moved his body so quickly that the speed of the action was compared to the swift opening and closing of a camera’s shutter."[18]

S. E. Dahlinger, leading expert on the play Sherlock Holmes, summed him up: "Without seeming to raise his voice or ever to force an emotion, he could be thrilling without bombast or infinitely touching without descending to sentimentality. One of his greatest strengths as an actor was the ability to say nothing at all on the stage, relying instead on an involved, inner contemplation of an emotional or comic crisis to hold the audience silent, waiting for the moment when he would speak again."[19]

He was an unemotional actor, unable to emote, even in love scenes, about which Montrose Moses commented, "he made appeal through the sentiment of situation, through the exquisite sensitiveness of outward detail, rather than through romantic attitude and heart fervor."[20]

Ward Morehouse described Gillette's style as "dry, crisp, metallic, almost shrill."[21] Gretchen Finletter recalled that it was "a dry, almost monotonous voice admirably suited to the great Holmes".[22] The New York Times noted in 1937 that "it would be hard to convince that portion of the American public that knew and followed him that any better actor had ever trod the American stage ... It would be conservative to say that Mr. Gillette was the most successful of all American actors."[23]

He had a heightened sense of the dramatic, and his two most riveting scenes are still considered to be among the most dramatic scenes in the history of the American theater: the hospital scene in Held by the Enemy and the Telegraph Office scene in Secret Service.[24]

Gillette treated both sides of the American Civil War equally, bestowing integrity, loyalty, and honor on both North and South, even as he made a spy each play's sympathetic hero. Yet, what set Gillette apart from all the rest was not simply his reliance on realism, his imperturbable naturalistic acting, or his superior sense of the dramatic. He "was also a pioneer in making American drama ‘American’, rejecting what had been up until that time a pervasive European influence on American theater" at a time when American art of all kinds was held in very low esteem by the British.[25]

Inventor

During an 1886–87 production of Held by the Enemy, Gillette introduced a new method of simulating the galloping of a horse. Men formerly had slammed halves of coconut shells on a slab of marble to simulate the sound, but Gillette found this clumsy and unrealistic. Patent No. 389,294 was applied for on June 9 and issued to him on September 11, entitled "Method of Producing Stage Effects". It was a method, not a mechanical device, so there were no illustrations in the two-page document. And the patent was very broad, introducing "a new and useful method of imitating the sound of a horse or horses approaching, departing, or passing at a gallop, trot, or any other desired gait, the same to be used in producing stage effects in theatrical or other performances or entertainments, exhibitions, &c."

His method consisted in "beating with clappers, that represent the hoofs of a horse, upon some material that serves to represent the road-bed over which the horse is supposed to be traveling" as well as "stamping, pawing, or jumping about in a restive manner while the rider is mounting, and then starting off, first at a trot, then a gallop, and finally a run, or at any gait desired, in any order". He could also imitate the sounds of the hoofs pounding on different surfaces: "stone, brick, clay, gravel, greensward, or when crossing bridges."[26]

It was not the first patent which he had applied for and received. In 1883, he filed the first of four patent requests with the United States Patent and Trademark Office for a Time-Stamp "as stamps upon the upper surface of papers a dial and one or more dial-pointers, representing the time of day at which the papers stamped by it were respectively so stamped." All four requests were granted.[27]

Comeback

Charles Frohman was a young Broadway producer who had been successful exchanging theater productions between the U.S. and the UK. After he produced some of Gillette's plays, the two formed a greater partnership. Their productions had great success, sweeping Gillette into London's society spot, which had been historically reluctant to accept American theatre. With Held by the Enemy in 1887, Gillette became the first American playwright to achieve true success on British stages with an authentic American play.[28]

Gillette finally came fully out of retirement in October 1894 in Too Much Johnson, adapted from the French farce La Plantation Thomassin by Maurice Ordonneau. Its debut was at the Park Theatre in Waltham, Massachusetts, then it opened on October 29 at the Columbia Theatre in Brooklyn. This farce was extremely popular, and has been produced on stage several times in the century since its debut.

In 1895, he wrote Secret Service, which was first performed in the Broad Street Theatre in Philadelphia for two weeks beginning on May 13, 1895, with Maurice Barrymore in the lead role. Gillette rewrote some of the script and starred in the play when it opened at the Garrick Theatre on October 5, 1896. It was the first time that he had taken on the role of the romantic hero in one of his own plays. The production ran until March 6, 1897 and was an enormous critical and popular success. Following its American success, Frohman booked Secret Service to open at the Adelphi Theatre on the West End in London on May 15, 1897, and it became the cornerstone of Frohman's achievements in England.

Sherlock Holmes

Meanwhile, Arthur Conan Doyle felt that the character of Sherlock Holmes was stifling him and keeping him from more worthy literary work. He had finished his Holmes saga and killed him off in The Final Problem published in 1893. Afterwards, however, Conan Doyle found himself in need of further income, as he was planning to build a new home called "Undershaw". He decided to take his character to the stage and wrote a play. Holmes had appeared in two earlier stage works by other authors in Charles Brookfield's skit Under the Clock (1893) and John Webb's play Sherlock Holmes (1894); nevertheless, Doyle now wrote a new five-act play with Holmes and Watson in their freshmen years as detectives.

Doyle offered the role first to Herbert Beerbohm Tree and then to Henry Irving. But Irving turned it down and Tree demanded that Doyle readapt Holmes to his peculiar acting profile; he also wanted to play both Holmes and Professor Moriarty. Doyle turned down the deal, considering that this would debase the character.

Literary agent A. P. Watt noted that the play needed a lot of work and sent the script to Charles Frohman, who traveled to London to meet Conan Doyle. There Frohman suggested the prospect of an adaptation by Gillette. Doyle endorsed this and Frohman obtained the staging-copyright. Doyle insisted on only one thing: there was to be no love interest in Sherlock Holmes. Frohman uttered a Victorian rendition of "Trust me!"

Gillette then read the entire collection for the first time, outlining the piece in San Francisco while still touring in Secret Service. On one occasion, after they had exchanged numerous telegrams about the play, Gillette telegraphed Conan Doyle: "May I marry Holmes?" Doyle responded: "You may marry him, or murder or do what you like with him."[29]

Milestones

New Holmes Play

Gillette's Sherlock Holmes consisted of four acts combining elements from several of Doyle's stories. He mainly utilized the plots "A Scandal in Bohemia" and "The Final Problem". Also, it had elements from A Study in Scarlet, The Sign of Four, The Boscombe Valley Mystery, and The Greek Interpreter. However, all the characters in the play were Gillette's own creations with the exception of Holmes, Watson, and Moriarty. His creation of Billy the Buttons (Pageboy) was later used by Doyle for "The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone". Gillette portrayed Holmes as brave and open to express his feelings, which was substantially different from the intellectual-only original, "a machine rather than a man". He wore the deerstalker cap on stage, which was originally featured in illustrations by Sidney Paget.

Props and Famous Phrase

Gillette introduced the curved or bent briar pipe instead of the straight pipe pictured by Strand Magazine's illustrator Sidney Paget, most likely so that Gillette could pronounce his lines more easily; a straight pipe can wiggle or fall when speaking, or cause problems with declaring lines while it is clenched between the teeth. It is less difficult to pronounce lines clearly with a curved pipe. Some have lately theorized that a straight pipe may have obscured Gillette's face. This could not happen with a curved briar in his mouth.

Gillette also made use of a magnifying-glass, a violin, and a syringe, which all came from the Canon and which were all now established as "props" to the Sherlock Holmes character. Gillette formulated the complete phrase: "Oh, this is elementary, my dear fellow", which was later reused by Clive Brook, the first spoken-cinema Holmes, as: "Elementary, my dear Watson", Holmes's best known line and one of the most famous expressions in the English language.

Characters

Irene Adler was "The Woman" of the Holmes canon, but she was replaced by Alice Faulkner, a young and beautiful lady who was planning to avenge her sister's murder but eventually fell in love with Holmes; and the pageboy, nameless in the Canon, was given the name Billy by Gillette, a name that he carried over into the Basil Rathbone films and has retained ever since. Sherlock Holmes, or The Strange Case of Miss Faulkner (later renamed Sherlock Holmes – A Drama in Four Acts) was finished.

Baldwin Hotel and Theater Fire

The Secret Service company was playing in San Francisco and staying in the Baldwin Hotel when a fire swept from the property room of the Baldwin Theatre through the hotel in the early morning hours of November 23. The play's script was in the possession of Gillette's secretary William Postance, in his room at the Baldwin Hotel. The financial loss was estimated at nearly $1,500,000. Only two deaths were known at first, though several people were missing. The flames were confined to the Baldwin, smoke and water damaged the adjoining structures.[30]

Gillette's secretary barely escaped, but the entire script was reduced to ashes. Postance went to the Palace Hotel where Gillette was sound asleep, and awakened him at 3:30 in the morning to break the bad news. Gillette was not overly happy about being disturbed in the middle of the night and simply asked, "Is this hotel on fire?" Assured that it was not, he told Postance, "Well, come and tell me about it in the morning."[31] Both manuscripts were destroyed — Conan Doyle's original and Gillette's adaptation — but Gillette rewrote the piece in a month, either from notes or an extra copy. Conan Doyle and Gillette had never met, so Conan Doyle's shock was understandable, once the two finally arranged a meeting, when the train carrying Gillette came to a halt and Sherlock Holmes himself stepped onto the platform instead of the actor, complete with deerstalker cap and gray ulster. Sitting in his landau, Conan Doyle contemplated the apparition with open-mouthed awe until the actor whipped out a magnifying lens, examined Doyle's face closely, and declared (precisely as Holmes himself might have done), "Unquestionably an author!"[32] Conan Doyle broke into a hearty laugh and the partnership was sealed with the mirth and hospitality of a weekend at Undershaw. The two men became lifelong friends.

Holmes tour

_(edit).jpg)

Lithograph – 1900

Library of Congress Collection

After a copyright performance in England, Sherlock Holmes debuted on October 23, 1899 at the Star Theatre in Buffalo, followed by appearances in Rochester and Syracuse, New York and in Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Sherlock Holmes made its Broadway debut at the Garrick Theater on November 6, 1899, performing until June 16, 1900. It was an instant success. Gillette applied all his dazzling special effects over the massive audience.

The company also toured nationally along the western United States from October 8, 1900 until March 30, 1901. This was bolstered by another company with Cuyler Hastings touring through minor cities and Australia. After a pre-debut week in Liverpool, the company debuted in London (September 9, 1901) at the Lyceum Theatre, performing in Duke of York's Theatre later.

It was another hit with its audience, despite not convincing the critics. The 12 weeks originally appointed were at full-hall. The production was extended until April 12, 1902 (256 presentations), including a gala for King Edward VII on February 1. Then it toured England and Scotland[33] with two ancillary groups: North (with H. A. Saintsbury) and South (with Julian Royce). At the same time, the play was produced in foreign countries (such as Australia, Sweden, and South Africa).

Sir Henry Irving was touring America when Sherlock Holmes opened at the Garrick Theatre, and Irving saw Gillette as Holmes. The two actors met and Irving concluded negotiations for Sherlock Holmes to begin an extended season at the Lyceum Theatre in London beginning in early May. Gillette was the first American actor ever to be invited to perform on that illustrious stage, which was an enormous honor. Irving was the dean of British actors, the first ever to be knighted, and the Lyceum was his theater.[34]

Sherlock Holmes made its British debut at the Shakespeare Theatre in Liverpool on September 2, 1901. It was the beginning of a major triumph. Gillette then opened Sherlock Holmes at the Lyceum in London on September 9. The Lyceum tour alone netted Gillette nearly $100,000, and it made the most money of all the productions in the final years of Irving's tenure at the Lyceum. In the United States, Gillette again toured from 1902 until November 1903, starring in The Admirable Crichton by James M. Barrie. Gillette's own play Electricity appeared in 1910, and he starred in Victorien Sardou's Diplomacy in 1914, Clare Kummer's A Successful Calamity in 1917, Barrie's Dear Brutus in 1918, and Gillette's The Dream Maker in 1921. A brief revival of Sherlock Holmes in early 1923 did not generate enough interest to return to Broadway, so he retired to his Hadlyme estate.[35]

Worldwide fame

In his lifetime, Gillette presented Sherlock Holmes approximately 1,300 times (third in the historical stage-record), before American and English audiences. He was also shown widely, through appearances in many editions of the Sherlock Holmes canon and in magazines by way of photographs or illustrations, and was also well represented on the covers of theater programs.

Around the world, other productions took place, based on Gillette's Sherlock Holmes. These were often satirical or parodical, which were sometimes successful enough to last several seasons. Frohman's lawyers tried to curb the illegal phenomenon exhaustedly, traveling overseas, from court to court. Legitimate productions were also produced throughout Europe and Australia for many years.[36]

Even Gillette parodied it once. The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes – the first of a handful of one-act plays he would write – was written for two benefits, and was performed for the first time at the Joseph Jefferson Holland Benefit at the Metropolitan Opera House on March 24. Holland was an actor who had been forced to retire the year before due to illness. The skit featured five characters: Holmes, Billy the page boy (played by Henry McArdle), the madwoman Gwendolyn Cobb (who had nearly all of the dialogue and was played by Ethel Barrymore), and the two "valuable assistants" who come to take the madwoman away. Its original title was A fantasy in about one-tenth of an act, and the entire scene transpires in Holmes' Baker Street room "somewhere about the date of day before yesterday."[37] Retitled The Harrowing Predicament of Sherlock Holmes, it was performed again on April 14 for the benefit of the Actors Society of America at the Criterion Theatre (with Jessie Busley as Gwendolyn Cobb and McArdle again as Billy), and again at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London when Gillette inserted it on October 3 as a curtain-raiser for Clarice. Playing Billy in the curtain-raiser was young Charlie Chaplin. When Clarice was replaced with Sherlock Holmes, Chaplin continued as Billy.[38]

Models for Holmes' portrait

The magazines Collier's Weekly (USA) and The Strand (UK) pushed Conan Doyle avidly, offering to continue the Sherlock Holmes series for a generous salary. The new stories were resumed in 1901, first with a prequel (The Hound of the Baskervilles) and then with Holmes actually revived in 1903 (in The Empty House). The Holmes series continued for another quarter-century, culminating with the bound edition of The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes in 1927.

Gillette was the model for pictures by the artist Frederic Dorr Steele, which were featured in Collier's Weekly then and reproduced by American media. Steele contributed to Conan Doyle's book-covers, later doing marketing when Gillette made his farewell performances. Conan Doyle's series were widely printed throughout the USA, with either Steele's illustrations or photographs of Gillette on stage.[39]

In 1907 Gillette was caricatured in Vanity Fair by Sir Leslie Ward (who signed his work "Spy") (see above),[40] and later became the subject of such famous American caricaturists as Pamela Colman Smith,[41] Ralph Barton and Al Freuh.[42]

Gillette Castle

While most of Gillette's work has long been forgotten, his last great masterpiece is still well known today: Gillette Castle in Hadlyme, Connecticut.

The castle sits atop a hill, part of the Seven Sisters chain, over the Chester–Hadlyme Ferry's peir. The design of the castle and its grounds features numerous innovative designs, and the entire castle was designed, to the smallest details, by Gillette.

The material for the castle was carried up by a tramway designed by him. During the five years of construction from 1914 to 1919,[43] he lived aboard his houseboat, the Aunt Polly, named after a mountain woman in South Carolina who tended to him when he was sick, or at a home he had purchased in Greenport, Long Island. The mansion was finished in 1919, at a cost of USD $1.1 million. Gillette called it "Seventh Sister."

His miniature railroad was his personal pride. The train's layout was 3 miles (4.8 km) long, and it traveled all around the property, crossing several bridges and going through one tunnel designed by Gillette.[44][45] The train was relocated after his death to an amusement park, Lake Compounce in Bristol, Connecticut, from 1943 through the mid-90s. Since then, both locomotives have been returned to the Castle, where one has been restored and is on display in the Visitors Center.

Gillette had no children and, after he died, his will stated

"I would consider it more than unfortunate for me – should I find myself doomed, after death, to a continued consciousness of the behavior of mankind on this planet – to discover that the stone walls and towers and fireplaces of my home – founded at every point on the solid rock of Connecticut; – that my railway line with its bridges, trestles, tunnels through solid rock, and stone culverts and underpasses, all built in every particular for permanence (so far as there is such a thing); – that my locomotives and cars, constructed on the safest and most efficient mechanical principles; – that these, and many other things of a like nature, should reveal themselves to me as in the possession of some blithering saphead who had no conception of where he is or with what surrounded."[46]

In 1943, the Connecticut state government bought the property,[43] renaming it Gillette's Castle and Gillette Castle State Park. Located in 67 River Road, East Haddam, Connecticut, it was reopened in 2002. After a four-year restoration costing $11 million, it now includes a museum, park, and many theatrical celebrations. It receives 100,000 annual visitors. The castle is No. 86002103 on the National Register of Historic Places.[47] It remains one of the top three tourist attractions in the state.

For some thirty years, Harold and Theodora Niver, both former members of the Baker Street Irregulars of New York, have impersonated William and Helen Gillette for various celebrations at Gillette Castle.[48]

Last years and farewell tour

Gillette announced his retirement many times throughout his career, despite not actually accomplishing this until his death. The first announced retirement took place after the start of the 20th century, after he purchased the boat Aunt Polly which was 144 feet (44 m) in length and weighed 200 tons.

Sherlock Holmes was Gillette's foremost production with 1,300 performances (in 1899–1901, 1905, 1906, 1910, 1915, 1923, and 1929–1932). While performing on other tours, he was always forced by popular demand to include at least one extra performance of Sherlock Holmes. In 1929, at the age of 76, Gillette started the farewell tour of Sherlock Holmes, in Springfield, Massachusetts. Scheduled for two seasons, it was eventually extended into 1932. The first run of the tour included in the cast Theatre Guild actress Peg Entwistle as Gillette's female lead. Entwistle was the tragic young actress who committed suicide by jumping from the Hollywoodland sign in 1932.[49]

In the New Amsterdam Theater of New York, on November 25, 1929, a great ceremony took place. Gillette received a signature book, autographed by 60 different world eminences. In a letter to Gillette, Arthur Conan Doyle stated: "I consider the production a personal gratification ... My only complaint is that you made the poor hero of the anemic printed page a very limp object as compared with the power of your own personality which you infuse into his stage presentment". Former President Calvin Coolidge commented that the production was a "public service". Booth Tarkington told him, "I would rather see you play Sherlock Holmes than be a child again on Christmas morning."[50]

Gillette's last appearance on stage was in Austin Strong's Three Wise Fools in 1936.[51]

Death

Gillette died on April 29, 1937, aged 83, in Hartford, due to a pulmonary hemorrhage.[52] He was buried in the Hooker family plot at Riverside Cemetery, Farmington, Connecticut, next to his wife.

Bibliography

Gillette wrote 13 original plays, 7 adaptations and some collaborations, encompassing farce, melodrama and novel adaption. Two pieces based on the Civil War remain his greatest works: Held by the Enemy (1886) and Secret Service (1896). Both were successful with both the public and the critics, and Secret Service remains the only one of his plays available today on commercial VHS and DVD from a 1977 Broadway Theater Archive production starring John Lithgow and Meryl Streep.

His own bibliography follows:

- Bullywingle the Beloved (performed in Hartford, Connecticut, October 3, 1872, again in March 1873)

- The Twins of Siam (July 1879; never produced)

- The Professor (Summer 1879 tryout in Columbus, Ohio)

- Esmeralda (adapted from short story by Frances Hodgson Burnett, October 29, 1881, Madison Square Theatre, New York; published by the Madison Square Theatre in 1881)

- Digby’s Secretary, also known as The Private Secretary (adapted from Gustave Von Moser's Der Bibliothekar, September 29, 1884, New York Comedy Theatre, New York).

- Der Bibliothekar, February 9, 1885, Madison Square Theatre, New York)

- Held by the Enemy (February 22, 1886, Criterion Theatre, Brooklyn, New York; published by Samuel French Ltd. in 1898)

- She (Dramatization of novel by Rider Haggard, November 29, 1887, Niblo's Garden, New York)

- A Legal Wreck (August 14, 1888, Madison Square Theatre, New York; published by the Rockwood Publishing Company in 1890)

- A Legal Wreck (Novelization, Rockwood Pub. Co., 1888)

- A Confederate Casualty (1888; never produced)

- Robert Elsmere (Partial dramatization of novel by Mary Augusta Ward; unable to obtain Mrs. Ward's permission, Gillette discontinued work on the project, and it was dramatized by other playwrights and produced without his participation)

- "Mr. William Gillette Surveys the Field", Harper's Weekly, Vol. XXXIII, No. 1676, February 2, 1889, Supplement, pp. 98–99

- All the Comforts of Home (adapted from Carl Lauf's Ein Toller Einfall, March 3, 1890, Boston Museum, Boston, Massachusetts; published by H. Roorbach in 1897)

- Maid of All Work (1890; never produced)

- Mr. Wilkinson's Widows (adapted from Alexandre Bisson's Feu Toupinel, March 23, 1891, National Theatre, Washington, D.C.)

- Settled Out of Court (adapted from Alexandre Bisson's La Famille Pont-Biquet, August 8, 1892, Fifth Avenue Theatre, New York)

- The War of the American Revolution (January 1893, "nine scenes with historical commentary, written for the ‘Barnum & Baily people’, for a libretto to use with their ‘Vast Episodic Drama of the Revolution")

- Ninety Days (February 6, 1893, Broadway Theatre, New York)

- Too Much Johnson (adapted from Maurice Ordonneau's La Plantation Thomassin, November 26, 1894, Standard Theatre, New York; published in 1912)

- Secret Service (May 13, 1895, Broad Street Theatre, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; published in 1898; published by Samuel French Ltd. in 1898)

- "The Tale of My First Success," New York Dramatic Mirror, The Christmas Number 1886, December 26, 1896, pg. 30

- Because She Loved Him So (October 28, 1898, Hyperion Theatre, New Haven, Connecticut)

- Sherlock Holmes (with Arthur Conan Doyle, October 23, 1899, Star Theatre, Buffalo, New York; published by Samuel French, Ltd., in 1922, by Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., in 1935, and by Doubleday in 1976 and 1977)

- "The House-Boat in America," The Outlook Magazine, Vol. 65, No. 5, June 2, 1900

- The Frightful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes (March 24, 1905, Joseph Jefferson Holland Benefit, Metropolitan Opera House; later retitled The Harrowing Predicament of Sherlock Holmes and finally The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes, published by Ben Abramson of The Argus Book Shop in Chicago in 1955)

- Clarice (September 4, 1905, Liverpool, England)

- Ticey, or That Little Affair of Boyd’s (June 15, 1908, originally retitled A Private Theatrical, then retitled A Maid-of-All Work, later retitled That Little Affair of Boyd’s, Columbia Theatre, Washington, D.C.)

- Samson (adapted from Henri Bernstein's Samson, October 19, 1908, Criterion Theatre, New York)

- The Red Owl, originally titled The Robber (One-Act Play, August 9, 1909, London Coliseum; published in One-Act Plays for Stage and Study, Second Series, Samuel French, Ltd., 1925, pp. 47–80)

- Among Thieves (One-Act Play, September 6, 1909, Palace Theatre, London; published in One-Act Plays for Stage and Study, Second Series, Samuel French, Ltd., 1925, pp. 246–267)

- Electricity (September 26, 1910, Park Theatre, Boston, Massachusetts; published by Samuel French Ltd. in 1924)

- Theatrical managers exposed; A few words from Mr. William Gillette at the annual dinner of the Theatrical Managers' Association of Greater New York, at the Knickerbocker Hotel, January 10, 1910 (New York, 1910).

- Secret Service: Being the Happenings of a Night in Richmond in the Spring of 1865 (Novelization, Dodd, Mead and Company, New York, and Kessinger Publishing in the United Kingdom, 1912)

- Butterfly on the Wheel (1914; never produced)

- Diplomacy (adapted from Victorien Sardou’s Dora, October 20, 1914, Empire Theatre, New York)

- William Hooker Gillette: The Illusion of the First Time in Acting (The Dramatic Museum of Columbia University in Papers on Acting, Second Series, Number 1, 1915)

- "When a Play Is Not a Play", Vanity Fair, Vol. 5, Nos. 5–7 – vol. 6, Nos. 2–4, January–June 1916, pg. 53

- Introduction to How to Write a Play, edited by Miles Dudley, Papers on Playmaking II (Dramatic Museum of Columbia University, 1916), pp. 1–8

- How Well George Does It (1919, never produced; published by Samuel French Ltd. in 1936)

- "America's Great Opportunity", The World War: Utterances Concerning Its Issues and Conduct by Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Printed for It's Archives and For Free

- The Dream Maker (November 21, 1921, Empire Theatre, New York)

- Sherlock Holmes, A Play (Samuel French, Ltd., 1922).

- Winnie and the Wolves (dramatized from Bertram Atkey's stories in the Saturday Evening Post, May 14, 1923, Lyric Theatre, Philadelphia, PA)

- The Astounding Crime on Torrington Road (Harper & Brothers, 1927)

- The Crown Prince of the Incas (1932–36; never completed)

- Sherlock Holmes, A Play (Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1935); Introduction by Vincent Starrett; Preface by William Gillette; Reminiscent notes and drawings by Frederic Dorr Steele

- Secret Service: Being the Happenings of a Night in Richmond in the Spring of 1865, Novelization with Cyrus Townsend Brady (Grosset & Dunlap in New York, 1936)

- Sherlock Holmes a Play: Wherein is Set Forth the Strange Case of Miss Alice Faulkner (Helan Halbach, Publisher, Santa Barbara, California, 1974), reprint of the 1935 edition; Introduction by Vincent Starrett; Preface by William Gillette; Reminiscent notes and drawings by Frederic Dorr Steele

- Sherlock Holmes: A Play (Doubleday & Company, 1976; hardcover).

- Sherlock Holmes: A Play (Samuel French, 1976; softcover)

- Sherlock Holmes: A Play (Doubleday & Company, 1977; hardcover)[53]

Patents issued by United States Patent and Trademark Office

Time-Stamp

- Letters patent No. 289,404, filed April 25, 1883, granted December 4, 1883.

- Letters Patent No. 300,966, filed May 2, 1883, granted June 24, 1884.

- Letters Patent No. 302,559, filed on May 14, 1883, and granted July 29, 1884.

- Letters Patent No. 309,537, filed December 5, 1883, and granted December 23, 1884.

Method of Producing Stage Effects

- Letters Patent No. 389,294, filed June 9, 1887, granted September 11, 1887.[54]

Audio/Visual

- Fox Movietone News: "Sherlock Holmes" Turns Engineer [Newsclip of William Gillette], featuring William Gillette (Fox, 1927, two minutes, sound, b&w, 35mm). Also heard in William Gillette: A Connecticut Yankee and the American Stage, Connecticut Heritage Productions, Peter Loffredo, Producer, SDF-V7, debuted on Connecticut Public Television on July 11, 1994.

- Sherlock Holmes (1934), recorded by G. Robert Vincent for his private collection; Gillette reads excerpts from Sherlock Holmes; Dr. F.C. Packard from Harvard University takes the part of Dr. Watson. Running Time: 9.8 min; from An Inventory of Spoken Word Audio Recordings in the Vincent Voice Library, Michigan State University (DB7455).3; also in the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

- William Gillette, Voice of: Selections from Sherlock Holmes and The Celebrated Jumping Frog (1934), addressing Professor F. C. Packard's class at Harvard University, imitates his old friend and neighbor Mark Twain in a reading of the early sentences of The Celebrated Frog of Calaveras County, Harvard Vocarium.[55]

Filmography

- 1915 – Esmeralda, directed by James Kirkwood and starring Mary Pickford, released on September 6, 1915, and re-released July 27, 1919

- 1916 – Sherlock Holmes, starring Gillette in the first cinema-adaptation of his Sherlock Holmes, albeit not the first film about Holmes. It was a seven-reel silent film by Essanay Film Manufacturing Co. directed by Arthur Berthelet.[56] Marjorie Kay played Alice Faulkner and Ernest Maupain was Moriarty. After years of being thought a lost film, a copy of the film was found in October 2014 at the Cinematheque Francaise and is undergoing restoration. It is believed to be the only record of Gillette playing the role on camera.[57]

- 1919 – Secret Service, Paramount Pictures, directed by Hugh Ford with Robert Warwick in Gillette's role of Captain Thorne and Shirley Mason as the female lead.

- 1919 – Too Much Johnson, Paramount Pictures – Director: Donald Crisp; Writers: William Gillette and Thomas J. Geraghty; Release Date: December 1919; Starring Bryant Washburn as Augustus Billings, Lois Wilson as Mrs. Billings, and Adele Farrington as Mrs. Batterson; 5 reels, 4,431 feet

- 1920 – Held by the Enemy, Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, Paramount Pictures – Director: Donald Crisp; Writers: William Gillette and Beulah Marie Dix; Release Date: October 24, 1920; Starring Agnes Ayers as Rachel Hayne, Wanda Hawley as Emmy McCreery, Lewis Stone as Capt. Gordon Haine, Jack Holt as Colonel Charles Prescott, and Robert Cain as Brigade Surgeon Fielding; 6 reels

- 1922 – Sherlock Holmes, Goldwyn Pictures, based on Gillette's play, directed by Albert Parker. John Barrymore played Holmes. William Powell made his screen debut as Foreman Wells in this film, restored by the George Eastman House

- 1931 – Secret Service, Radio Pictures, directed by J. Walter Ruben with Richard Dix as Captain Thorne

- 1937 – Too Much Johnson, Mercury Theatre Company, Director: Orson Welles; Writers: William Gillette and Orson Welles; Starring Joseph Cotten as Augustus Billings and Ruth Ford as Mrs. Billings. It was to be inserted into a stage production of the play but was never shown in public. Though Welles' print was destroyed in 1970, another one was discovered in 2013 and became available online the next year.

- 1977 – Secret Service, Broadway Theatre Archive, starring John Lithgow as Captain Thorne and Meryl Streep as Edith Varney. This was the first time Streep was seen on film, and it is the only play by Gillette still available on commercial VHS or DVD

- 1981 – Sherlock Holmes, Home Box Office in collaboration with the Williamstown Theater Festival and artistic director Nikos Psacharopoulos, and was broadcast on November 19, 1981, with repeats on November 23, 27, 29, and December 1 and 5. This production starred Frank Langella as Holmes, Stephen Collins as James Larrabee, Susan Clark as Madge Larrabee, Richard Woods as Dr. Watson, and 12-year-old Christian Slater in his film debut as Billy the Pageboy. This production is not available on commercial VHS or DVD.[58]

- 1982 – Sherlock Holmes, Guy Dumur translated Gillette’s play into French for the 1982 filming of Sherlock Holmes, starring fifty-four-year-old Paul Guers as Holmes. Directed by Jean Hennin, it was broadcast on October 5, 1982[59]

Radio

- On October 20, 1930, Gillette performed the first serial radio-version of Sherlock Holmes: The Adventure of the Speckled Band. It was based on the original theater version by Conan Doyle, re-adapted by Edith Meiser, and was the first time Holmes was portrayed on radio as part of a continuing series. It was transmitted by WEAF-NBC (New York) and sponsored by G. Washington Coffee Co.. This show became the pilot of a series and, after Gillette, Richard Gordon took over the part for the remaining 34 programs in the series.[60]

- On November 18, 1935, Gillette, now 82 years old, performed his own Sherlock Holmes on WABC radio of New York. His play was again re-adapted by Meiser. Reginald Mason played Dr. Watson and Charles Bryant played Professor Moriarty. Its duration was 50 minutes. This play was the pilot for a new Holmes series by Lux Radio Theater. The New York Times said that Gillette was "still the best, with all his shades and improvisation".[61]

As novelist

- 1927, The Astounding Crime on Torrington Road—his only mystery novel.[62]

Tryon, North Carolina

In 1891, after first visiting Tryon, North Carolina, Gillette began building his bungalow, which he later enlarged into a house. He named it Thousand Pines and it is privately owned today. In past years, in November, the town of Tryon celebrated the William Gillette Festival, honoring Gillette. The Polk County Historical Museum there displays Gillete's pipe and slippers from his farewell tour of Sherlock Holmes, as well as china, some letters and other items left behind at the actor's North Carolina home.[63]

New York City

On December 7, 1934, Gillette attended the first dinner meeting of the Baker Street Irregulars in New York. As of 2011, the BSI continues its William Gillette Memorial Luncheon on the Friday afternoon of their annual January meeting in New York City (Baker Street Irregulars Weekend, The Annual Gathering of the oldest Literary Society dedicated to Sherlock Holmes).

Famous namesake

Among Gillette's friends was actress Gertrude Berkeley. Gertrude had a son whom she apparently named after two of her friends, actress Amy Busby and William Gillette, after Busby and Gillette agreed to be the boy's godparents. The son's name was Busby Berkeley William Enos who, as Busby Berkeley, became one of Hollywood's greatest directors and choreographers.[64]

Quotations

- "Elementary, my dear fellow! Elementary!"[65]

- "There isn’t any reason in the world why we can’t do as well in this farewell business as any other country on the face of the globe. We have the farewellers and the people to say farewell to. If I can only keep it up I will be even with my competitors by the Spring of 1922, and by the Winter of 1937 I will be well in the lead."[66]

- "It just seems, somehow, that every five years finds me back again, so you can expect me back at it again once more in 1941. Probably in 1976, when they are celebrating the two-hundredth anniversary of the beginning of the Declaration of Independence, or what ever it is, 40 years from now, I'll still be farewelling. I should apologize for being here, but I am a man among Yankees, and they take promises with a grain of salt – in fact they usually take them home and pickle them in brine, so they probably knew I'd be back. Besides I have several good excuses – but they really don't count. And besides – and you men who follow horse racing will know what I mean – I'm not running against anyone, they're merely letting me trot around the track."[67]

- "Farewell, Good Luck, and Merry Christmas."[67]

References

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes (Xlibris Press, 2011), pp. 7, 9, 28, 328, 581.

- ↑ Riley, Dick; Pam McAllister (2005). The Bedside Companion to Sherlock Holmes. Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-0-7607-7156-3.; Zecher website, ibid.

- ↑ Hartford Courant, "Mr. Gillette’s Play In London", April 4, 1887, pg. 1; The Times, "Princess's Theatre", April 4, 1887, pg. 5; Price, E. D., FGS, Editor, Hazell;s Annual Cyclopedia (Hazell, Watson, and Viney, 1888), pg. 191; Deshler, Welch, Editor, The Theatre, Vol. III, No. 6, April 25, 1887, Whole No. 58, in The Theatre (Theatre Publishing Company, 1888), pg. 107; New York Times, "Old World News by Cable", May 15, 1887, pg. 1; New York Morning Journal, "‘Held by the Enemy’, the Story of Its Phenomenal Success", September 11, 1887, pg. 9; Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 161–163.

- ↑ See Andrews, Kenneth R., Nook farm, Mark Twain's Hartford Circle (Harvard University Press, 1950) and Van Why, Joseph S., Nook Farm (Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT, 1975).

- ↑ Andrews, Kenneth R., Nook Farm, Mark Twain's Hartford Circle (Harvard University Press, 1950).

- ↑ Hooker, Edward W., The Descendants of Rev. Thomas Hooker: Hartford, Connecticut, 1586–1908 (Edited by Margaret Huntington Hooker and printed for her at Rochester, N.Y., 1909; Legacy Reprint Series, Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007).

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, p. 51.

- ↑ Sacramento Daily Union, August 8, 1859, notice, compiled by David Murray, Superintendent of the City Cemetery, reads: Mortality of the City. In the 1860 Mortality Schedule Index at the California State Library in Sacramento is an entry under Gillett, Frank A.; age 23; male; CT listed for state of birth; died Aug; listed as Farmer for occupation; died Sacramento County; enumeration district 2; township Sacramento City.

- ↑ Burton, Nathaniel J., A Discourse Delivered January 29th, 1865, in Memory of Robert H. Gillette (Press of Wiley, Waterman & Eaton), 1865.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles M., III, Hurricane of Fire, the Union Assault on Fort Fisher (Naval Institute Press, 1998), pg. 184; Gragg, Rod, Confederate Goliath, the Battle of Fort Fisher (Harper Collins, 1991), pg. 235; Hartford Courant, "Death of Paymaster Gillette", January 21, 1865, pg. 2; Burton, Nathaniel J., A Discourse Delivered January 29, 1865, in Memory of Robert H. Gillette; Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, p. 55-56.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, p. 77; Duffy, Richard, "Gillette, Actor and Playwright", Ainslee's Magazine, Vol. VI, No. 1, August 1900, pg. 54.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, p. 77; Letter to George Warner, Gillette Correspondence, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

- ↑ Last Will of Francis Gillette, Signed October 12, 1877, City of Hartford Probate Records, 1876–1880, Microfilm #LDS1314362, CSL #986, continued on LDS #987, pp. 435–436, 539–541.

- ↑ Helen Gillette Death Certificate, Office of Vital Statistics, Office of the Town Clerk, Town Hall, Greenwich, Connecticut, September 1, 1888.

- ↑ Frohman, Daniel, Daniel Frohman Presents An Autobiography (Claude Kendall & Willoughby Sharp, 1935), pg. 51; Gerzina, Gretchen, Frances Hodgson Burnett (Chatto & Windus,2004), pp. 89, 93–95, 99; Gillette, William, Esmeralda in The Century Magazine, Vol. XXIII, New Series VOL I, November 1881 to April 1882 (The Century Co., 1882), pp. 513–531; Hartford Courant, "Amusements, ‘Esmeralda’", November 6, 1882, pg. 3; New York Times, "Mrs. Burnett's New Play", October 30, 1881, pg. 8

- ↑ Leslie, Amy, Some Players (Hebert S. Stone & Company, 1899), pg. 302

- ↑ Strang, Lewis C., Famous Actors of the Day in America (L.C. Page and Company, 1900), pg. 178.

- ↑ Schuttler, George William, William Gillette, Actor and Director (An unpublished thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Speech Communication in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, 1975), pg. 97; Schuttler, Georg William, (1983) "William Gillette: Marathon Actor and Playwright," The Journal of Popular Culture, Vol. 17, Issue 3, Winter 1983, pp. 115–29. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1983.1703_115.x, pp. 124–5.

- ↑ Dahlinger, S. E., "The Sherlock Holmes We Never Knew," Baker Street Journal, Vol. 49, No. 3, September 1999, pg. 10.

- ↑ Moses, Montrose J., The American Dramatist (Little, Brown, and Company, 1925), pg. 369

- ↑ Morehouse, Ward, Matinee Tomorrow (Whittlesey House, 1949), pg. 23

- ↑ Finletter, Gretchen, From the Top of the Stairs (Little, Brown, 1946), pg. 44

- ↑ New York Times, "William Gillette, Actor, Dead at 81", April 30, 1937, pg. 21

- ↑ Murphy, Brenda, American Realism and American Drama, 1880–1940 (Cambridge University Press, 1987), pg. 162; Dithmar, Edward, "Secret Service", Harper's Weekly, October 10, 1896, pg. 215

- ↑ Films for the Humanities & Sciences

- ↑ Letters Patent No. 389,294, "Method of Producing Stage Effects", September 11, 1887, U.S. Patent Office

- ↑ United States Patent and Trademark office, Letters Patent No. 289,404, Filed April 25, 1883, granted December 4, 1883; Letters Patent No. 300,966, filed May 2, 1883, granted June 24, 1884; Letters Patent No. 302,559, filed on May 14, 1883, and approved July 29, 1884; and Letters Patent No. 309,537, filed December 5, 1883, and issued December 23, 1884.

- ↑ New York Sun Journal, September 11, 1887, quoted in Schuttler, Georg William, William Gillette, Actor and Playwright, p. 11; Price, E. D., FGS, Editor, Hazell's Annual Cyclopedia (London: Hazell, Watson, and Viney, 1888), p. 191; Deshler, Welch, Editor, The Theatre, Vol. III, No. 6, April 25, 1887, Whole No. 58, in The Theatre (Theatre Publishing Company, 1888), p. 107; London Times, "Princess's Theatre", April 4, 1887, pp. 3, 5; London Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan, Memories and Adventures (Wordsworth Editions Limited, 2007), pg. 87; Starrett, Vincent, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes(The MacMillan Company, 1933), pg. 139

- ↑ New York Times, "San Francisco Hotel Fire, ‘Lucky’ Baldwin's House Laid in Ruins by Flames, Loss of Life May Be Great, Only Two Victims' Bodies So Far Recovered – Theatre in the Building Also Burned", November 24, 1898, pg. 1

- ↑ Shepstone, Harold J., "Mr. William Gillette as Sherlock Holmes", The Strand Magazine, April 1901, pg. 615

- ↑ Higham, Charles, The Adventures of Conan Doyle, the life of the creator of Sherlock Holmes (W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1976), pp. 153–4; Encyclopedia Sherlockiana, "Gillette, William" (MacMillan, 1994), pg. 90

- ↑ Cullen, Rosemary, & Don B. Wilmeth, Plays by William Hooker Gillette (Cambridge University Press, 1983), pg. 16 Plays by William Gillette, Rosemary Cullen, Don B. Wilmeth.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, ‘’William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes,’’ pp. 314–316; London Times, "Death or Sir Henry Irving," October 14, 1904, p. 6.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, ‘’William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes,’’ p. 488.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, ‘’William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes,’’ pp. 329–31.

- ↑ Gillette, William H., The Painful Predicament of Sherlock Holmes (Ben Abramson, 1955).

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 356, 358–59; Chaplin, Charlie, My Autobiography (Simon & Schuster, 1964), p. 89

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, p. 327.

- ↑ "Sherlock Holmes", Vanity Fair, February 27, 1907, Front Cover

- ↑ Smith, Pamela Colman, William Gillette As Sherlock Holmes (R. H. Russell, 1900)

- ↑ Celebrity Caricature in America

- 1 2 http://www.connecticutmag.com/Connecticut-Magazine/June-2014/Gillette-King-of-Connecticut-Castles-Opens-for-Summer-Season/

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 423–37, 503–08

- ↑ "Sherlock Holmes Builds Miniature Railroad", October 1930, Popular Mechanics

- ↑ Gillette, William, Last Will and Testament, 1/27/37; Hartford Courant, "Gillette Will Requests His Home Not Be Sold To ‘Blithering Saphead’", May 4, 1937, pg. 1

- ↑ 9 National Register of Historic Places www.nationalregisterof historicplaces.com/CT/New+London/state4.html.

- ↑ http://sherlockholmesct.com/testimonials.html

- ↑ Los Angeles Times, "Girl Leaps To Death From Sign," September 19, 1932, p. A1.

- ↑ Letters of Salutation and Felicitation Received by William Gillette on the Occasion of His Farewell to the Stage in Sherlock Holmes (1929)

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 557–68.

- ↑ William Gillette Medical Certificate of Death, Connecticut State Department of Health, signed by Dr. John A. Wentworth, April 29, 1937

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 591–93.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, p. 595

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 595–96.

- ↑ Andrew Pulver; Kim Willsher (2 October 2014). "'Holy grail' of Sherlock Holmes films discovered at Cinémathèque Française". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ↑ "Lost Sherlock Holmes film found in France after 100 years". CBC News. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J., "TV: H.B.O. Offers 'Sherlock Holmes'", The New York Times, November 19, 1981.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 593–595.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 531–38.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 555–557.

- ↑ Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes, pp. 496–503.

- ↑ Read about Tryon's 1998 Festival

- ↑ Spivak, Jeffrey, Buzz: The Life and Art of Busby Berkeley (University Press of Kentucky, 2010), pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Gillette, William, Sherlock Holmes, A Play, Wherein Is set forth The Strange Case of Miss Alice Faulkner (Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1935), pg. 82

- ↑ New York Times, "The Au Revoir Tour," October 17, 1915, Fashions Society Queries Summer White House Music & Drama Pages Hotels & Restaurants, p. X8

- 1 2 Hartford Courant, "Death Seals Last Gillette Retirement", April 30, 1937, pp. 1, 6

Sources

- Cook, Doris E., Sherlock Holmes & Much More (The Connecticut Historical Society, 1970).

- Doyle, Arthur Conan, & Jack Tracy, editor, Sherlock Holmes: The Published Apocrypha (Houghton Mifflin; 1st Ed. Edition, 1980).

- Haining, Peter, The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Apocryphile Press, 2005).

- Zecher, Henry, William Gillette, America's Sherlock Holmes (Xlibris Press, 2011).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Gillette. |

- William Gillette at the Internet Movie Database

- William Gillette Introduction

- The Baker Street Journal – writings about Sherlock Holmes

- Gillette Castle State Park in East Haddam, Connecticut

- William Gillette at Find a Grave

- Gillette Castle Train Restored & Unveiled on YouTube

- Portrait of William Gillette; University of Washington, Sayre collection

- William Gillette Portrait gallery; NY Public Library, Billy Rose collection

- William Gillette; PeriodPaper.com about 1910

- Website for biographer Henry Zecher.

- Theatre posters from performances of Held by the Enemy at Royal Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh in 1887

- Works by William Gillette at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Gillette at Internet Archive

|