Heinz Guderian

| Heinz Wilhelm Guderian | |

|---|---|

|

Heinz Guderian on the Eastern Front, July 1941 | |

| Nickname(s) |

Schneller Heinz (Fast Heinz) Hammering Heinz[1] |

| Born |

17 June 1888 Kulm, West Prussia, German Empire now Chełmno, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland |

| Died |

14 May 1954 (aged 65) Schwangau, Allgäu, Bavaria, West Germany |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1907–45 |

| Rank | Generaloberst |

| Commands held |

2. Panzer Division XVI. Armeekorps XIX. Armeekorps Panzergruppe Guderian/Panzergruppe 2/2. Panzerarmee |

| Battles/wars | |

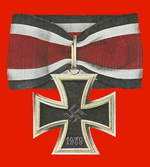

| Awards | Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub |

| Relations | Heinz-Günther Guderian |

Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (German: [ɡuˈdeʀi̯an]; 17 June 1888 – 14 May 1954) was a German general during World War II, noted for his success as a leader of Panzer units in Poland and France and for partial success in the Soviet Union.

Guderian had pioneered motorized tactics in the pre-war army, while keeping himself well-informed about tank development in other armies. In particular, he promoted the use of radio communication between tank-crews, and devised shock-tactics that proved highly effective. In 1940, he led the Panzers that broke the French defences at Sedan, France, leading to the surrender of France. In 1941, his attack on Moscow was delayed by orders from Hitler with whom he disagreed sharply. After the German defeat at the Battle of Moscow he was transferred to the reserve. This marked the end of his ascendancy.

After the defeat at Stalingrad, Hitler appointed him to a new post, rebuilding the shattered Panzer forces, but he feuded with many other generals, who managed to get his responsibilities re-allocated. He was then appointed Chief of the General Staff of the Army, but this was largely a symbolic post, since Hitler had effectively become his own Chief of Staff. From 1945-48, Guderian was held in U.S. custody, but released without charge. He then advised on the re-establishment of military forces in West Germany.

Early life and education

Guderian was born in Kulm, West Prussia (now Chełmno, Poland), the son of Clara (Kirchoff) and Friedrich Guderian.[2][3] From 1901 to 1907 Guderian attended various military schools. He entered the Army in 1907 as an ensign-cadet in the (Hanoverian) Jäger-Bataillon No. 10, commanded at that point by his father. After attending the war academy in Metz he was made a Leutnant (full Lieutenant) in 1908. In 1911 Guderian joined the 3rd Telegraphen-Battalion of the Prussian Army Signal Corps. On 1 October 1913 he married Margarete Goerne with whom he had two sons, Heinz-Günter (2 August 1914 – 2004) and Kurt (17 September 1918 – 1984). Both sons became highly decorated Wehrmacht officers during World War II; Heinz-Günter became a Panzer general in the Bundeswehr after the war.

First World War

At the outset of World War I Guderian served as a Signals Officer in the 5th Cavalry Division. After completing a practical war course, on 28 February 1918 Guderian was appointed to the General Staff Corps, which he described as 'the proudest moment of my life'.[4] This allowed him to get an overall view of battlefield conditions. He often disagreed with his superior officers. He was transferred to the intelligence department of the army, where he remained until the end of the war. Like many Germans, he disagreed with Germany signing the armistice in 1918, believing the German Empire should have continued the fight.[5]

Interwar period

Early in 1919, Guderian was selected as one of the four thousand officers to continue on in military service for the reduced size German army, the Reichswehr. He was assigned to serve on the staff of the central command of the Eastern Frontier Guard Service. This Guard Service was intended to control and coordinate the independent Freikorps units in the defense of Germany's eastern frontiers against Polish and Soviet forces engaged in the Russian Civil War.[6] In June 1919, Guderian joined the Iron Brigade (later known as the Iron Division) as its second General Staff officer.[7] The commanders of the regular German army had intended that this move would allow the army to reassert its control over the Iron Division; however, their hopes were disappointed. Rather than restrain the Freikorps, Guderian's anti-communism caused him to empathize with the Iron Division's efforts to defend Prussia against the Soviet threat. The Iron Division waged a ruthless campaign in Lithuania and pushed into Latvia; however, traditional German anti-Slavic attitudes prevented the division's full cooperation with the White Russian and Baltic forces opposing the Bolsheviks.[8]

Guderian was assigned as a company commander for the 10th Jäger-Battalion. Later he joined the Truppenamt ("Troop Office"), which was a clandestine form of the Army's General Staff which had been officially forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles. In 1927 Guderian was promoted to major and transferred to the command of Army transport and motorized tactics in Berlin. This placed Guderian at the center of German development of armoured forces. Guderian, who was fluent in both English and French, studied the works of British maneuver warfare theorists J. F. C. Fuller, Giffard Martel and B.H. Liddell Hart. In 1931, he was promoted to Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) and became chief of staff to the Inspectorate of Motorized Troops under Oswald Lutz. In 1933 he was promoted to Oberst or Colonel.

Guderian wrote many papers on mechanized warfare during this period. These papers were based on extensive study of the lessons of the First World War, research on foreign literature on the use of armour, and wargaming done with dummy tanks and later with early armoured vehicles. Some of these trial maneuveres were conducted in Soviet Russia. Britain at this time was experimenting with tanks under General Hobart, and Guderian kept abreast of Hobart's writings using, at his own expense, someone to translate all the articles being published in Britain.[9]

In October 1935 he was made commander of the newly created 2nd Panzer Division (one of three). On 1 August 1936 he was promoted to Generalmajor, and on 4 February 1938 he was promoted to Generalleutnant and given command of the XVI Army Corps.[10]

In 1936 General Lutz asked Guderian to write a book on the developing panzer arm and the theories that had been developed on its use in war.[11] The book produced, Achtung - Panzer!, was his most important work. It reviewed the state of armoured development in the European nations and Soviet Russia, and presented Guderian's theories on the effective use of armoured formations and combined-arms warfare ideas of other general staff officers. The book included the importance of airpower in support of the panzer units for future ground combat.

Germany's panzer forces were created largely along the lines laid down by Guderian in Achtung - Panzer!

Mobile warfare

Toward the end of World War I, the German army had increasingly adopted infiltration tactics — the idea of breaking through a defensive front with special combat teams or sturmtruppen, who would bypass strong points and get behind the enemy position to cause it to collapse. These methods were used in its 1918 Spring Offensive, but the breakthroughs achieved could not be capitalized upon because the forces lacked the mobility to exploit the move and create a deep penetration of the enemy defenses. Ultimately they failed to gain decisive results as they were unable to sustain the impetus of the initial attack.

Motorized infantry was the key to sustaining a breakthrough, and until the 1920s the extent of motorization necessary was not possible. Soviet marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky pursued the idea, but he was executed in 1937 as a part of Stalin's "Great Purge" of his military's leadership.

Guderian developed and advocated the strategy of concentrating armoured formations at the point of attack (Schwerpunkt) and deep penetration. In "Achtung Panzer" he described what he believed were essential elements for a successful panzer attack. Three elements were listed: surprise, deployment in mass, and suitable terrain.[12] He proposed and created armoured divisions whose motorized infantry and artillery supported the armoured units to achieve a decisive success. In his book Panzer Leader he wrote:

In this year (1929) I became convinced that tanks working on their own or in conjunction with infantry could never achieve decisive importance. My historical studies; the exercises carried out in England and our own experience with mock-ups had persuaded me that the tanks would never be able to produce their full effect until weapons on whose support they must inevitably rely were brought up to their standard of speed and of cross-country performance. In such formation of all arms, the tanks must play the primary role, the other weapons being subordinated to the requirements of the armour. It would be wrong to include tanks in infantry divisions: what were needed were armoured divisions which would include all the supporting arms needed to fight with full effect. [13]

Guderian believed that among those things needed for success was the ability of commanders to communicate with their mobile units. Guderian insisted in 1933 that the tanks in the German armoured force be equipped with radio- and visual equipment in order to enable each tank commander to communicate with his crew and with the tanks in his platoon and company.[14] Inside the individual tanks, the German tank crews worked as a team, and the tank commander had the means to communicate with each of his crew members. Moreover, the German tanks worked collectively as a team, working together for mutual protection and increased firepower.[15] Said Hermann Balck: "The decisive breakthrough into modern military thinking came with Guderian, and it came not only in armour, but in communication."[16] Of those things Guderian contributed, Balck considered some of the most important were the five man tank crew, with a dedicated radio operator in the hull of the tank, and the operation of the signal organization in the division to allow the commander to direct the division from any unit. This allowed forward control of the division, which was critical to mobile warfare.[17] The German victories from 1939 through 1941 were not due to superior equipment, but to superior tactics in the use of that equipment, and superior command and control which allowed the German panzer forces to operate at a much higher pace.

Second World War

Poland

Guderian led the XIX Corps during the invasion of Poland. This corps comprised a panzer division and two motorized infantry divisions. Guderian led his corps in the Battle of Wizna and the Battle of Kobryn. In each of these his theories of rapid maneuver in combat proved highly successful.

Following the completion of the campaign in Poland the armoured forces were transferred to the west to prepare for the next set of operations. The four light divisions had proved to have inadequate firepower, and they were brought up to strength to full panzer divisions, one of which was given to Erwin Rommel. With this change the total number of panzer divisions in the Heer stood at ten. Guderian continued to work in development of the panzer arm. Said Hans von Luck of the 7th Panzer Division in his memoir: "In the middle of February we were transferred to Dernau on the Ahr, hence practically in to the western front. Rommel visited every unit. He told us that he was proud to be permitted to lead a panzer division. Guderian too came to inspect and talk to us. 'You are the cavalry' he told us. 'Your job is to break through and keep going.'"[18]

France

In the planning for the Invasion of France, Guderian supported the change in the attack plan from a massive headlong invasion through the Low Countries to the Manstein Plan shifting the weight of the armoured formations to the Ardennes. Guderian's corps spearheaded the drive and were through the Ardennes and over the Meuse in three days. He led the attack that broke the French lines at Sedan, resulting in a general collapse of the French defenses. His guidance of the panzer formations earned him the nickname "Der schnelle Heinz" (Fast Heinz).[19] Guderian's panzer group led the "race to the sea" that split the Allied armies in two, depriving the French armies and the BEF in Northern France and Belgium of their fuel, food, spare parts and ammunition. Faced with orders from nervous superiors to halt on one occasion, he managed to continue his advance by stating he was performing a 'reconnaissance in force'. Guderian's column was famously denied the chance to destroy the Allied forces trapped in the pocket at Dunkirk by an order coming from high command.

Soviet Union

In 1941 he commanded Panzergruppe 2, also known as Panzergruppe Guderian, during Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The unit later was redesignated Second Panzer Army. He became the 24th recipient of the Oak Leaves to his previously-awarded Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross on 17 July of that year after his armoured spearhead captured Smolensk. Poised to launch the final assault on Moscow, he was ordered to turn his army south in an effort to encircle the Soviet forces to the south. He protested the decision.

Following the completion of the encirclement and the Battle of Kiev, Guderian was ordered to make a drive for Moscow in mid-September 1941.[20] With winter fast approaching, the effort seemed fraught with the risk of over-extending and leaving his command subject to counter-attack. He was ordered to proceed anyway. The offensive weakened and though several units under Guderian's command made it to the outskirts of Moscow, the city remained in Soviet control. The Soviets then launched a counterattack that sent the German forces reeling and threatened a general collapse. [21] Guderian was not allowed to pull his forces back, but instead was ordered to "stand fast" in their current positions. He disputed the order, going personally to Adolf Hitler's headquarters. The order was not changed. After returning to his command, he carried out a series of withdrawals anyway, in direct contradiction of his orders. A heated series of disputes with Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge, the commander of Army Group Centre, then followed. After a final clash with von Kluge, Guderian asked to be relieved of his command. On 26 December 1941 Guderian was relieved, along with 40 other generals. He was transferred to the reserve pool. Guderian held hard feelings on the matter against von Kluge, whom he felt failed to support him.

In September 1942, when Erwin Rommel was recuperating in Germany from health problems, he suggested Guderian to OKW as the only man suitable to replace him in Africa. The response from OKW came in the same night: "Guderian is not accepted".[22][N 1]

Inspector General of Armoured Troops

After the German defeat at Stalingrad Hitler realized he was in need of Guderian's expertise. He personally requested Guderian to take a new position as "Inspector General of Armoured Troops". Guderian made a number of stipulations to ensure that he would have the requisite authority to perform his duties. Hitler agreed to these conditions, and on 1 March 1943 he was appointed to the newly created position. His responsibilities were to oversee the rebuilding of the greatly weakened panzer arm, to oversee tank design and production, and the training of Germany's panzer forces, and he was to advise Hitler on their use. His new position allowed him to bypass much of the Nazi bureaucracy and report to Hitler directly.

Guderian was opposed by a number of officers in the Wehrmacht who did not want to see the scope of their own power and influence curtailed. Said Hermann Balck, who had worked with Guderian at the Inspectorate of Mobile Troops "Guderian was always in conflict with everybody else. He was very hard to get along with, and it's a tribute to the German Army, as well as to Guderian's own remarkable abilities, that he was able to rise as high as he did within the German Army."[16] The primary area of resistance to Guderian came from the artillery branch.[24] In an effort to curtail Guderian's influence an adjective was added to his areas of oversight, changing the term "assault guns", which was becoming an increasingly important area of firepower for the panzer divisions, to "heavy assault guns" which was far more limited. The addition of the qualifier "heavy" removed the Stug III, Wespe and Hummel from Guderian's responsibility, meaning that 90% of assault gun production, training and use would be outside of Guderian's influence.[25]

Operation Citadel, the last major German offensive operation in the east, was an attempt by the German army to regain the initiative. Unfortunately for German planners, their designs were known by the Soviet defenders, who spent months building up a defense in depth to sap the strength of the attacking panzer units. The operation violated two of the three tenets for successful tank operations that Guderian had laid out in Achtung – Panzer!, namely that terrain for the operation had to be chosen that was open, and not built up with heavy defenses. Secondly, and more importantly, the strike had to be delivered in a manner that took the defenders by surprise. In light of the obvious heavy defenses the Soviets had been preparing for the attack; the operation was a clear misuse of the Panzerwaffe. The result would be a significant weakening of the panzer forces, forces that Guderian had been trying to rebuild. In a conversation with Hitler on 14 May 1943 Guderian pointed out the futility of the operation, asking: "My Führer, why do you want to attack in the East at all this year?" To which Hitler responded: "You are quite right. Whenever I think of this attack my stomach turns over." Guderian concluded, "In that case your reaction to the problem is the correct one. Leave it alone."[26]

When the head of the OKW General Wilhelm Keitel explained the political importance of the offensive, Guderian remarked "How many people do you think even know where Kursk is? It's a matter of profound indifference to the world whether we hold Kursk or not..."[27]

The attack, originally planned for May, was not launched until July. It went on for a week before Soviet pressures on the Orel salient to the north and the necessity to respond to the allied invasion of Sicily resulted in the operation being halted. The Soviets then seized the initiative, which they held for the remainder of the war.

In his role as Inspector General of Armoured Troops, Guderian observed that Hitler was prone to experiment with too many designs, rather than finding an effective design and produce it in large numbers. He believed this resulted in supply-, logistical-, and repair problems for German forces in the Soviet Union.[28] Guderian would have preferred the production of larger numbers of Panzer IVs and Panthers, and less energy and engineering effort spent on such projects as the Jagdtiger, the super tank Panzer VIII Maus, and the 800 mm railway gun the Schwerer Gustav.

Chief of Staff of the Army

On 21 July 1944, after the failure of the 20 July Plot to assassinate Hitler, in which Guderian had no direct involvement, Guderian was appointed Chief of Staff of the Army (Chef des Generalstabs des Heeres) succeeding Kurt Zeitzler who had departed on 1 July after multiple conflicts with Adolf Hitler.

Later life and death

Guderian and his staff surrendered to U.S. forces on 10 May 1945. He remained as a prisoner of war in U.S. custody until his release on 17 June 1948. His conduct was investigated and no charges were brought. After the war he was often invited to attend meetings of British veterans' groups, where he analyzed past battles with his old foes. During the early 1950s he advised on the reestablishment of military forces in West Germany. The reformed military was called the Bundeswehr.

Guderian died on 14 May 1954 at the age of 65, in Schwangau near Füssen in (Southern Bavaria) and is buried at the Friedhof Hildesheimer Straße in Goslar.

Notes written by Erwin Rommel while convalescing from injuries suffered in Normandy offered the following perspective into the development of armoured warfare in Germany:

In Germany the elements of modern armoured warfare had already crystallized into a doctrine before the war—thanks mainly to the work of General Guderian—and had found practical expression in the organization and training of armoured formations.[29]

A documentary about his life aired on French television in 2000. Titled Guderian, it was directed by Anton Vassil and featured Guderian's son Heinz-Günther, Field Marshal Lord Carver and historians Kenneth Macksey and Heinz Wilhelm.

The Enigma machine used by Guderian is on display at the Intelligence Corps museum in Chicksands, Bedfordshire, England.

Controversies

Disputes with Hitler

Guderian was one of the few generals to openly challenge Hitler over the way in which Germany was pursuing the war. A number of conflicts arose. Following the German victory in the Battle of France, Hitler ordered an increase in the number of panzer divisions from ten to twenty. This was accomplished by splitting up their panzer regiments. More formations were created but their strength was diluted. This decreased their power, while doubling the need for support equipment and personnel. Guderian opposed the weakening of the panzer formations. Later, in his efforts to rebuild the panzer forces, Guderian argued for the removal of the panzer crews from Africa in early 1943, as their skill and experience were difficult to replace and their tanks had been lost in the conflict, but Hitler refused to take them off the continent.[30] In addition, over the course of the war, as material and replacement crews became available, Hitler ordered the creation of new panzer formations. Guderian wanted the men and material to be used to bring the existing formations up to strength.[31] Hitler believed the creation of new formations gave him a political advantage, in that it gave the appearance that Germany was still strong. However, these formations and their inexperienced crews were not nearly as effective as the veteran formations, and the result was many unnecessary losses.[32] Most importantly, Hitler was unwilling to give up any ground that his soldiers had taken. This resulted in a rigid defense that did not allow his forces the opportunity to maneuver to better counter the moves of their enemy, or to withdraw to shorten their frontage or prevent encirclement. Positions were held onto until it was no longer possible for them to withdraw. The result was that a great number of German formations were surrounded and destroyed unnecessarily. Guderian was outspoken in his opposition to these policies which placed so little value on the lives of the German soldiers.

Guderian was dismissed twice, first on 26 December 1941 and again on 28 March 1945. The last dismissal followed a shouting-match over the loss of the German forces encircled at Küstrin. The forces trapped there were not allowed to break out, and General Theodor Busse's 9th Army was unable to fight their way through the Soviets to reach them. Guderian was informed that "your physical health requires that you immediately take six weeks convalescent leave".[33] He was replaced by General Hans Krebs.

Appropriation of estate

After the invasion of Poland a large number of estates were seized by the German government. Hitler attempted to engender loyalty in key commanders by offering them financial gifts. Following his success in Poland Guderian was given 2,000 acres (810 ha) at Deipenhof (now Głębokie) in the Warthegau area of occupied Poland. The occupants were evicted.[34] Guderian told Erich von Manstein that he was given a list of Polish estates that he studied for a few days before deciding which to claim for his own. After the war Guderian allegedly changed the dates and circumstances of the situation in his memoirs to present the takeover of the estate as a legitimate retirement gift.[35][36]

Other

Following their disagreement over the defeat before Moscow, Günther von Kluge challenged Heinz Guderian to a duel in 1943. Günther von Kluge requested Adolf Hitler to act as his second. Duels were illegal in Germany at this time, and Hitler forbade it.

Many years later in 1997 Israeli military theorist Shimon Naveh cast aspersions on Guderian, stating he was complicit in supporting a false claim by B.H. Liddell Hart. This was part of Naveh's efforts to undermine Liddell Hart's influence over the Israeli military, and on closer inspection his accusations proved to be groundless (see the Naveh controversy).

Awards and decorations

- Iron Cross (1914)

- Knight 2nd class of the Friedrich Order with Swords (Württemberg) (15 December 1915)[37]

- Saxe-Ernestine House Order Commander 2nd Class with Swords (1 July 1935)[37]

- Wehrmacht Long Service Award 1st Class (1 October 1936)[37]

- Royal Hungarian War Memorial Medal with Swords (14 January 1937)[37]

- Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918[37]

- War Memorial Medal with Swords (Austria) (9 March 1937)[38]

- Anschluss Medal (13 March 1938)[38]

- Sudetenland Medal with Prague Castle Bar (1 October 1938)[39]

- Order of St. Sava 1st Class (21 November 1939)[38]

- Clasp to the Iron Cross (1939)

- Panzer Badge in Silver[39]

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves

- Knight's Cross on 27 October 1939 as General der Panzertruppe and commander of the XIX Army Corps[39][40]

- 24th Oak Leaves on 17 July 1941 as Generaloberst and commander of Panzer Gruppe 2[39][41]

- Mentioned 5 times in the Wehrmachtbericht (6 August 1941, 7 August 1941, 21 September 1941, 18 October 1941 and 19 October 1941)[39]

Wehrmachtbericht references

| Date | Original German Wehrmacht Report wording | Direct English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Thursday, 7 August 1941 | Am Verlauf dieser gewaltigen Schlacht waren die Armeen des Generalfeldmarschalls von Kluge und der Generalobersten Strauß und Freiherr von Weichs, die Panzergruppen der Generalobersten Guderian und Hoth sowie die Luftwaffenverbände der Generale der Flieger Loerzer und Freiherr von Richthofen ruhmreich beteiligt.[42] | During the course of this great battle, the armies of Field Marshal von Kluge and the Colonel General Strauß and Freiherr von Weichs, the Panzer groups of Colonel-General Guderian and Hoth, and the Luftwaffe detachments of the generals of the Air Loerzer and Freiherr von Richthofen were involved gloriously. |

| Saturday, 18 October 1941 | (Sondermeldung) An der Durchführung dieser Operationen waren die Armeen des Generalfeldmarschalls von Kluge, der Generalobersten Freiherr von Weichs und Strauß sowie Panzerarmeen der Generalobersten Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner und des Generals der Panzertruppen Reinhardt beteiligt.[43] | (Special Bulletin) In the execution of these operations were involved, the armies of Field Marshal von Kluge, the Colonel-Generals Freiherr von Weichs and Strauss as well as tank armies of Colonel-General Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner and General of Panzer Troops Reinhardt. |

| Sunday, 19 October 1941 | An der Durchführung dieser Operationen waren die Armeen des Generalfeldmarschalls von Kluge, der Generalobersten Freiherr von Weichs und Strauß sowie Panzerarmeen der Generalobersten Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner und des Generals der Panzertruppen Reinhardt beteiligt.[44] | In the execution of these operations were involved, the armies of Field Marshal von Kluge, the Colonel-Generals Freiherr von Weichs and Strauss as well as tank armies of Colonel-General Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner and General of Panzer Troops Reinhardt. |

See also

Works

- Guderian, Heinz (1937). Achtung - Panzer! (reissue ed.). Sterling Press. ISBN 0-304-35285-3. Guderian reviews the development of armoured forces in the European nations and Soviet Russia, and describes what he felt was essential for the effective use of armoured forces.

- Guderian, Heinz (1942). Mit Den Panzern in Ost und West. Volk & Reich Verlag.

- Guderian, Heinz (1950). Kann Westeuropa verteidigt werden?. Plesse-Verlag.

- Guderian, Heinz (1952). Panzer Leader. Da Capo Press Reissue edition, 2001. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81101-4. Guderian describes his time as an officer in charge of various German armoured forces. Originally published in German, titled Erinnerungen eines Soldaten (Memories of a Soldier) (Kurt Vowinckel Verlag, Heidelberg 1950; 10th edition 1977).

Notes

- ↑ The exchange was recalled by General Fritz Bayerlein, who related it to Liddell Hart.[23]

References

Citations

- ↑ Boot 2006, p. 223.

- ↑ Guderian 1937, p. 7.

- ↑

- ↑ Barnett 1989, p. 442.

- ↑ Hargreaves 2009, p. 29.

- ↑ Hart 2006, p. 16.

- ↑ Hart 2006, p. 17.

- ↑ Hart 2006, p. 18.

- ↑ Shepperd 1990, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Guderian 1952, p. 47.

- ↑ Zimmer 2013, p. 13.

- ↑ Guderian 1937, p. 205.

- ↑ Guderian 1952, p. 15.

- ↑ Zimmer 2013, p. 12.

- ↑ Guderian 1952, p. 20.

- 1 2 Balck 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ Balck 2000, p. 18.

- ↑ Luck 1989, p. 36.

- ↑ Guderian 1952, p. 108.

- ↑ Barnett 1989, p. 453.

- ↑ Barnett 1989, p. 454.

- ↑ Lewin p. 153

- ↑ Rommel 1982, p. 227.

- ↑ Balck 2000, p. 31.

- ↑ Clark 1965, p. 313.

- ↑ Healy p. 23

- ↑ Clark 1965, p. 325.

- ↑ Guderian 1952.

- ↑ Rommel 1982, p. 520.

- ↑ Guderian 1952, p. 304.

- ↑ Guderian 1952, pp. 297, 303.

- ↑ Balck 2000, p. 47.

- ↑ Guderian 1952, pp. 427–428.

- ↑ James V. Koch, review of Guderian: Panzer General by Kenneth Macksey

- ↑ Corrupt Histories Emmanuel Kreike, William Chester Jordan, page 123, University of Rochester Press 2005

- ↑ Beevor 2002, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wegmann 2009, p. 204.

- 1 2 3 Wegmann 2009, p. 205.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miller, Michael D. "Generaloberst Heinz Guderian". Axis Biographical Research. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 171.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 50.

- ↑ Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, p. 639.

- ↑ Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, pp. 701–702.

- ↑ Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, p. 702.

Bibliography

- Alman, Karl (2008). Panzer vor - Die dramatische Geschichte der deutschen Panzerwaffe und ihre tapferen Soldaten [Panzer ahead - The dramatic story of the German Panzer force and their brave soldiers] (in German). Würzburg, Germany: Flechsig Verlag. ISBN 978-3-88189-638-2.

- Balck, Hermann (2000). General Hermann Balck : an interview 12 January 1979. Bennington, Vermont: Merriam Press.

- Beevor, Antony (2002). Berlin: The Downfall 1945. Viking-Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.

- Boot, Max (2006). War made new: technology, warfare, and the course of history, 1500 to today. New York: Gotham Books. ISBN 9781592402229. LCCN 2006015518.

- Clark, Alan (1965). Barbarossa: The Russian-German Conflict 1941-45. New York: HarpersCollins. ISBN 978-0-688-04268-4.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Barnett, Correlli, ed. (1989). Hitler's Generals. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-79462-0.

- Guderian, Heinz (1937). Achtung - Panzer!. Sterling Press. ISBN 0-304-35285-3.

- Guderian, Heinz (1952). Panzer Leader. New York: Da Capo. ISBN 0-306-81101-4.

- Hargreaves, Richard (2009). Blitzkrieg w Polsce wrzesien 1939. Warsaw: Bellona.

- Hart, Russell A. (2006). Guderian: Panzer pioneer or myth maker?. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-59797-453-0.

- Luck, Hans von (1989). Panzer Commander: The Memoirs of Colonel Hans von Luck. Cassel Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-36401-0.

- Rommel, Erwin (1982) [1953]. Liddell Hart, B. H., ed. The Rommel Papers. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80157-0.

- Schaulen, Fritjof (2003). Eichenlaubträger 1940 – 1945 Zeitgeschichte in Farbe I Abraham – Huppertz [Oak Leaves Bearers 1940 – 1945 Contemporary History in Color I Abraham – Huppertz] (in German). Selent, Germany: Pour le Mérite. ISBN 978-3-932381-20-1.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Miltaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Shepperd, Alan (1990). France, 1940: Blitzkrieg in the West. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-958-6.

- Thomas, Franz (1997). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 1: A–K [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 1: A–K] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2299-6.

- Wegmann, Günter (2009). Die Ritterkreuzträger der Deutschen Wehrmacht 1939–1945 Teil VIIIa: Panzertruppe Band 2: F–H [The Knight's Cross Bearers of the German Wehrmacht 1939–1945 Part VIIIa: Panzer Force Volume 2: F–H] (in German). Bissendorf, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2389-4.

- Williamson, Gordon and Bujeiro, Ramiro (2004). Knight's Cross and Oak Leaves Recipients 1939-40. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-84176-641-0.

- Young, Desmond (1950). Rommel The Desert Fox. New York: Harper & Row. OCLC 48067797.

- Zimmer, Phil (October 2013). "Blitzkrieg Author". World War II History XII (6): 10–15.

- Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, 1. September 1939 bis 31. Dezember 1941 [The Wehrmacht Reports 1939–1945 Volume 1, 1 September 1939 to 31 December 1941] (in German). München, Germany: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. 1985. ISBN 978-3-423-05944-2.

Further reading

- Beevor, Antony, Berlin: The Downfall (2002)

- Corum, James, The Roots of Blitzkrieg (1992)

- Kershaw, Ian, Hitler 1936–1945: Nemesis (2001)

- Macksey, Kenneth, Guderian: Panzer General (1992, revision of Guderian, Creator of the Blitzkrieg, 1976)

- Searle, Alaric, Wehrmacht Generals, West German Society, and the Debate on Rearmament, 1949-1959, Praeger Pub., (2003).

- Walde, Karl J., Guderian (1978)

External links

- Heinz Guderian in the German National Library catalogue

- Personality Profile - General Heinz Guderian by the Journal of the Singapore Armed Forces

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by — |

Commander of 2. Panzer-Armee 5 October 1941 – 25 December 1941 |

Succeeded by Generaloberst Rudolf Schmidt |

| Preceded by Kurt Zeitzler |

Chief of Staff of the OKH July 1944 – March 1945 |

Succeeded by Hans Krebs |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Alexander Novikov |

Cover of Time Magazine 7 August 1944 |

Succeeded by Sir Arthur Coningham |

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|