Heat pump

A heat pump is a device that provides heat energy from a source of heat to a destination called a "heat sink". Heat pumps are designed to move thermal energy opposite to the direction of spontaneous heat flow by absorbing heat from a cold space and releasing it to a warmer one. A heat pump uses some amount of external power to accomplish the work of transferring energy from the heat source to the heat sink.

While air conditioners and freezers are familiar examples of heat pumps, the term "heat pump" is more general and applies to many HVAC (heating, ventilating, and air conditioning) devices used for space heating or space cooling. When a heat pump is used for heating, it employs the same basic refrigeration-type cycle used by an air conditioner or a refrigerator, but in the opposite direction - releasing heat into the conditioned space rather than the surrounding environment. In this use, heat pumps generally draw heat from the cooler external air or from the ground.[1] In heating mode, heat pumps are three to four times more efficient in their use of electric power than simple electrical resistance heaters. Typically installed cost for a heat pump is about 20 times greater than for resistance heaters.[2][3]

Overview

In heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) applications, the term heat pump usually refers to easily reversible vapor-compression refrigeration devices optimized for high efficiency in both directions of thermal energy transfer.

Heat spontaneously flows from warmer places to colder spaces. A heat pump can absorb heat from a cold space and release it to a warmer one. "Heat" is not conserved in this process, which requires some amount of external high grade (low-entropy) energy, such as electricity.

Heat pumps are used to provide heating because less high-grade energy is required for their operation than appears in the released heat. Most of the energy for heating comes from the external environment, and only a fraction comes from electricity (or some other high-grade energy source required to run a compressor). In electrically powered heat pumps, the heat transferred can be three or four times larger than the electrical power consumed, giving the system a coefficient of performance (COP) of 3 or 4, as opposed to a COP of 1 for a conventional electrical resistance heater, in which all heat is produced from input electrical energy.

Heat pumps use a refrigerant as an intermediate fluid to absorb heat where it vaporizes, in the evaporator, and then to release heat where the refrigerant condenses, in the condenser. The refrigerant flows through insulated pipes between the evaporator and the condenser, allowing for efficient thermal energy transfer at relatively long distances.

Reversible heat pumps

Reversible heat pumps work in either thermal direction to provide heating or cooling to the internal space. They employ a reversing valve to reverse the flow of refrigerant from the compressor through the condenser and evaporation coils.

- In heating mode, the outdoor coil is an evaporator, while the indoor is a condenser. The refrigerant flowing from the evaporator (outdoor coil) carries the thermal energy from outside air (or soil) indoors, after the vapour temperature has been augmented by compressing it. The indoor coil then transfers thermal energy (including energy from the compression) to the indoor air, which is then moved around the inside of the building by an air handler. Alternatively, thermal energy is transferred to water, which is then used to heat the building via radiators or underfloor heating. The heated water may also be used for domestic hot water consumption. The refrigerant is then allowed to expand, cool, and absorb heat to reheat to the outdoor temperature in the outside evaporator, and the cycle repeats. This is a standard refrigeration cycle, save that the "cold" side of the refrigerator (the evaporator coil) is positioned so it is outdoors where the environment is colder. In cold weather, the outdoor unit is intermittently defrosted by briefly switching to the cooling mode. This will cause the auxiliary or Emergency heating elements (located in the air-handler) to be activated. At the same time, the frost on the outdoor coil will quickly be melted due to the warm refrigerant. The condenser/evaporator fan will not run during defrost mode.

- In cooling mode the cycle is similar, but the outdoor coil is now the condenser and the indoor coil (which reaches a lower temperature) is the evaporator. This is the familiar mode in which air conditioners operate.

Operating principles

Mechanical heat pumps exploit the physical properties of a volatile evaporating and condensing fluid known as a refrigerant. The heat pump compresses the refrigerant to make it hotter on the side to be warmed, and releases the pressure at the side where heat is absorbed.

The working fluid, in its gaseous state, is pressurized and circulated through the system by a compressor. On the discharge side of the compressor, the now hot and highly pressurized vapor is cooled in a heat exchanger, called a condenser, until it condenses into a high pressure, moderate temperature liquid. The condensed refrigerant then passes through a pressure-lowering device also called a metering device. This may be an expansion valve, capillary tube, or possibly a work-extracting device such as a turbine. The low pressure liquid refrigerant then enters another heat exchanger, the evaporator, in which the fluid absorbs heat and boils. The refrigerant then returns to the compressor and the cycle is repeated.

It is essential that the refrigerant reaches a sufficiently high temperature, when compressed, to release heat through the "hot" heat exchanger (the condenser). Similarly, the fluid must reach a sufficiently low temperature when allowed to expand, or else heat cannot flow from the ambient cold region into the fluid in the cold heat exchanger (the evaporator). In particular, the pressure difference must be great enough for the fluid to condense at the hot side and still evaporate in the lower pressure region at the cold side. The greater the temperature difference, the greater the required pressure difference, and consequently the more energy needed to compress the fluid. Thus, as with all heat pumps, the coefficient of performance (amount of thermal energy moved per unit of input work required) decreases with increasing temperature difference.

Insulation is used to reduce the work and energy required to achieve a low enough temperature in the space to be cooled.

To operate in different temperature conditions, different refrigerants are available. Refrigerators, air conditioners, and some heating systems are common applications that use this technology.

Heat transport

Heat is typically transported through engineered heating or cooling systems by using a flowing gas or liquid. Air is sometimes used, but quickly becomes impractical under many circumstances because it requires large ducts to transfer relatively small amounts of heat. In systems using refrigerant, this working fluid can also be used to transport heat a considerable distance, though this can become impractical because of increased risk of expensive refrigerant leakage. When large amounts of heat are to be transported, water is typically used, often supplemented with antifreeze, corrosion inhibitors, and other additives.

Heat sources/sinks

A common source or sink for heat in smaller installations is the outside air, as used by an air-source heat pump. A fan is needed to improve heat exchange efficiency.

Larger installations handling more heat, or in tight physical spaces, often use water-source heat pumps. The heat is sourced or rejected in water flow, which can carry much larger amounts of heat through a given pipe or duct cross-section than air flow can carry. The water may be heated at a remote location by boilers, solar energy, or other means. Alternatively when needed, the water may be cooled by using a cooling tower, or discharged into a large body of water, such as a lake, stream or an ocean.

Geothermal heat pumps or ground-source heat pumps use shallow underground heat exchangers as a heat source or sink, and water as the heat transport medium. This is possible because below ground level, the temperature is relatively constant across the seasons, and the earth can provide or absorb a large amount of heat. Ground source heat pumps work in the same way as air-source heat pumps, but exchange heat with the ground via water pumped through pipes in the ground. Ground source heat pumps are more simple and therefore more reliable than air source heat pumps as they do not need fan or defrosting systems and can be housed inside. Although a ground heat exchanger requires a higher initial capital cost, the annual running costs are lower, because well-designed ground source heat pump systems operate more efficiently.

Heat pump installations may be installed alongside an auxiliary conventional heat source such as electrical resistance heaters, or oil or gas combustion. The auxiliary source is installed to meet peak heating loads, or to provide a back-up system.

Applications

There are millions of domestic installations using common air source electric heat pumps.[4] They are used in climates with moderate space heating and cooling needs (HVAC) and may also provide domestic hot water.[5] The purchase costs are supported in various countries by consumer rebates.[6]

HVAC

In HVAC applications, a heat pump is typically a vapor-compression refrigeration device that includes a reversing valve and optimized heat exchangers so that the direction of heat flow (thermal energy movement) may be reversed. The reversing valve switches the direction of refrigerant through the cycle and therefore the heat pump may deliver either heating or cooling to a building. In cooler climates, the default setting of the reversing valve is heating. The default setting in warmer climates is cooling. Because the two heat exchangers, the condenser and evaporator, must swap functions, they are optimized to perform adequately in both modes. Therefore, the efficiency of a reversible heat pump is typically slightly less than two separately optimized machines.

Plumbing

In plumbing applications, a heat pump is sometimes used to heat or preheat water for swimming pools or domestic water heaters; the heat energy removed from an air-conditioned space may be recovered for heating water.

District heating

Commissioned in 2011 this district heating extracts heat from a pond whose temperature is around 8 °C using 3 systems giving a combined capacity of 14 megawatts to town center residences and businesses. A city ordinance mandates this heating system for many new buildings.

Refrigerants

Until the 1990s, the refrigerants were often chlorofluorocarbons such as R-12 (dichlorodifluoromethane), one in a class of several refrigerants using the brand name Freon, a trademark of DuPont. Its manufacture was discontinued in 1995 because of the damage that CFCs cause to the ozone layer if released into the atmosphere [citation needed].

One widely adopted replacement refrigerant is the hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) known as R-134a (1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane). Heat pumps using R-134a are not as efficient as those using R-12 that they replace (in automotive applications) and therefore, more energy is required to operate systems utilizing R-134a than those using R-12. Other substances such as liquid R-717 ammonia are widely used in large-scale systems, or occasionally the less corrosive but more flammable propane or butane, can also be used.

Since 2001, carbon dioxide, R-744, has increasingly been used, utilizing the transcritical cycle, although it requires much higher working pressures. In residential and commercial applications, the hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) R-22 is still widely used, however, HFC R-410A does not deplete the ozone layer and is being used more frequently; however, it is a powerful greenhouse gas which contributes to climate change.[7][8] Hydrogen, helium, nitrogen, or plain air is used in the Stirling cycle, providing the maximum number of options in environmentally friendly gases.

More recent refrigerators use R600A which is isobutane, and does not deplete the ozone and is friendly to the environment.

Dimethyl ether (DME) is also gaining popularity as a refrigerant.[9]

Noise

Both indoor and outdoor heat pump units contain moving mechanical components which produce noise. In 2013, the CEN started work on standards for protection from noise pollution caused by heat pump outdoor units.[10] Although the CEN/TC 113 Business Plan outset was that "consumers increasingly require a low acoustic power of these units as the users and their neighbours now reject noisy installations", no standards for noise barriers or other means of noise protection were developed by January 2016.

Noise from outdoor units sometimes exceeds noise levels permitted by the legislation. For example, the 2015 data sheet of "Mr Slim" Zubadan Inverter Heat Pump informs whoever reads it, including the pump's owner neighbors, that Mr Slim's outdoor unit generates 52 dB(A) in the heating mode.[11] This is more than permitted by legislation in some countries, for example UK,[12] where this or similar pumps are used. Another example is Poland, where the noise level permitted in residential areas is 40 dB at night,[13] which is more than the UK limit (35 dB), but still makes Mr Slim's outdoor unit 12 dB beyond the limit. In the United States, the allowed nighttime noise level was defined in 1974 as "an average 24-hr exposure limit of 55 A-weighted decibels (dBA) to protect the public from all adverse effects on health and welfare in residential areas (U.S. EPA 1974). This limit is a day–night 24-hr average noise level (LDN), with a 10-dBA penalty applied to nighttime levels between 2200 and 0700 hours to account for sleep disruption and no penalty applied to daytime levels.[14] The 10-dB(A) penalty makes the permitted U.S. nighttime noise level equal to 45 dB(A) which is more than what is accepted in some European countries but less than the noise produced by some heat pumps.

Therefore, it is important to pay special attention to those heat pumps which are advertised as being extremely efficient and generating noise at a very low level, supposedly, at the same time. The simultaneousity of the two conditions being met together can be tested on the example of Toshiba Residential Super Daiseikai G2KVP Inverter Hiwall Heat Pump.[15] The product is advertised as having "extremely high efficiencies with 5.15 and a noise level of only 20 dB in ultra-low fan speed for the RAS-10G2KVP". It is possible to download a brochure by clicking at a pdf at the bottom of the site. The Technical Specifications are given on the last page of the Brochure and one can verify the correctness of the initial commercial information. The detail missing at the beginning is that the value of 20 dB(A) for RAS-10G2KVP only refers to the indoor unit in the quiet mode (42 dB(A) in the high mode) whereas the external unit produces 61 dB(A) in the Heating mode which is not reported in the commercial introduction. The level of 61 dB (A) exceeds the environmental noise limits worldwide.

The location of an outdoor unit in relation to the building wall has a meaning. The unit (1) shown on page 7 of the Heat Pump Product Brochure[16] published by American Standard® Heating&Conditioning is placed close to the center of the house wall, like a musician of the Symphony Orchestra playing a concerto. Shells and walls made of hard material are used behind a sound source if passive sound amplification is necessary. Such a location of the outdoor unit adds some extra dB(A) of noise reflected from the wall. The dB level is not reported in the brochure and the location of the neighbors' house is not shown in the picture, but this type of location should not be used close to a place planned as a quiet place even if the unit is quiet. The heat pump outdoor unit is not a musician performing in front of the audience.

Another feature of ASHP external heat exchangers is their need to stop the fan from time to time for a period of several minutes in order to get rid of frost[17] that accumulates in the outdoor unit in the heating mode. After that the heat pump starts to work again. This part of the work cycle results in two sudden changes of the noise made by the fan. The acoustic effect of such disruption on neighbors is especially powerful in quiet environment where background nighttime noise may be as low as 0 to 10dBA This is included in legislation in France. According to French notion of noise nuisance, the "noise emergence" is the difference between the ambient noise including the disturbing noise and the ambient noise without the disturbing noise.[18] [19] The emergence should be below 3 dB(A) at night (between 10.00 pm and 7.00 am), so the pump in France, once stopped at night, theoretically should not be allowed to switch on again until morning. In addition, the level of ambient noise including the disturbing noise must be below 30 dB(A) in France, which is definitely the condition impossible to be met without an effective sound barrier by most ASHPs which were commercially available by the end of 2015.

However, ASHP outdoor units are still installed in residential areas worldwide without any noise protection, as no recognized standards for heat pump outdoor noise barriers are available yet, as of January 2016.

Performance Considerations

When comparing the performance of heat pumps, it is best to avoid the word "efficiency", which has a very specific thermodynamic definition. The term coefficient of performance (COP) is used to describe the ratio of useful heat movement per work input. Most vapor-compression heat pumps use electrically powered motors for their work input.

According to the US EPA, geothermal heat pumps can reduce energy consumption up to 44% compared with air-source heat pumps and up to 72% compared with electric resistance heating.[20] Heatpumps in general have a COP of 4.2 to 4.6 which places it behind cogeneration with a COP of 9.[21]

When used for heating a building with an outside temperature of, for example, 10 °C, a typical air-source heat pump (ASHP) has a COP of 3 to 4, whereas an electrical resistance heater has a COP of 1.0. That is, one joule of electrical energy will cause a resistance heater to produce only one joule of useful heat, while under ideal conditions, one joule of electrical energy can cause a heat pump to move three or four joules of heat from a cooler place to a warmer place. Note that an air source heat pump is more efficient in hotter climates than cooler ones, so when the weather is much warmer the unit will perform with a higher COP (as it has a smaller temperature gap to bridge). When there is a wide temperature differential between the hot and cold reservoirs, the COP is lower (worse). In extreme cold weather the COP will go down to 1.0.

On the other hand, ground-source heat pumps (GSHP) benefit from the moderate temperature underground, as the ground acts naturally as a store of thermal energy.[22] Their year-round COP is therefore normally in the range of 2.5 to 5.0.

When there is a high temperature differential (e.g., when an air-source heat pump is used to heat a house with an outside temperature of, say, 0 °C (32 °F)), it takes more work to move the same amount of heat to indoors than on a milder day. Ultimately, due to Carnot efficiency limits, the heat pump's performance will decrease as the outdoor-to-indoor temperature difference increases (outside temperature gets colder), reaching a theoretical limit of 1.0 at −273 °C. In practice, a COP of 1.0 will typically be reached at an outdoor temperature around −18 °C (0 °F) for air source heat pumps.

Also, as the heat pump takes heat out of the air, some moisture in the outdoor air may condense and possibly freeze on the outdoor heat exchanger. The system must periodically melt this ice; this defrosting translates into an additional energy (electricity) expenditure.

When it is extremely cold outside, it is simpler to heat using an alternative heat source (such as an electric resistance heater, oil furnace, or gas furnace) rather than to run an air-source heat pump. Also, avoiding the use of the heat pump during extremely cold weather translates into less wear on the machine's compressor.

The design of the evaporator and condenser heat exchangers is also very important to the overall efficiency of the heat pump. The heat exchange surface areas and the corresponding temperature differential (between the refrigerant and the air stream) directly affect the operating pressures and hence the work the compressor has to do in order to provide the same heating or cooling effect. Generally, the larger the heat exchanger, the lower the temperature differential and the more efficient the system becomes.

Heat exchangers are expensive, requiring drilling for some heat-pump types or large spaces to be efficient, and the heat pump industry generally competes on price rather than efficiency. Heat pumps are already at a price disadvantage when it comes to initial investment (not long-term savings) compared to conventional heating solutions like boilers, so the drive towards more efficient heat pumps and air conditioners is often led by legislative measures on minimum efficiency standards. Electricity rates will also influence the attractiveness of heat pumps.[23]

In cooling mode, a heat pump's operating performance is described in the US as its energy efficiency ratio (EER) or seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER), and both measures have units of BTU/(h·W) (1 BTU/(h·W) = 0.293 W/W). A larger EER number indicates better performance. The manufacturer's literature should provide both a COP to describe performance in heating mode, and an EER or SEER to describe performance in cooling mode. Actual performance varies, however, and depends on many factors such as installation details, temperature differences, site elevation, and maintenance.

As with any piece of equipment that depends on coils to transfer heat between air and a fluid, it is important for both the condenser and evaporator coils to be kept clean. If deposits of dust and other debris are allowed to accumulate on the coils, the efficiency of the unit (both in heating and cooling modes) will suffer.

Heat pumps are more effective for heating than for cooling an interior space if the temperature differential is held equal. This is because the compressor's input energy is also converted to useful heat when in heating mode, and is discharged along with the transported heat via the condenser to the interior space. But for cooling, the condenser is normally outdoors, and the compressor's dissipated work (waste heat) must also be transported to outdoors using more input energy, rather than being put to a useful purpose. For the same reason, opening a food refrigerator or freezer has the net effect of heating up the room rather than cooling it, because its refrigeration cycle rejects heat to the indoor air. This heat includes the compressor's dissipated work as well as the heat removed from the inside of the appliance.

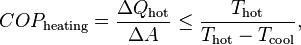

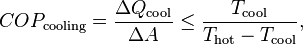

The COP for a heat pump in a heating or cooling application, with steady-state operation, is:

where

-

is the amount of heat extracted from a cold reservoir at temperature

is the amount of heat extracted from a cold reservoir at temperature  ,

, -

is the amount of heat delivered to a hot reservoir at temperature

is the amount of heat delivered to a hot reservoir at temperature  ,

, -

is the compressor's dissipated work.

is the compressor's dissipated work. - All temperatures are absolute temperatures usually measured in kelvins or degrees Rankine.

Coefficient of performance (COP) and lift

The COP increases as the temperature difference, or "lift", decreases between heat source and destination. The COP can be maximized at design time by choosing a heating system requiring only a low final water temperature (e.g. underfloor heating), and by choosing a heat source with a high average temperature (e.g. the ground). Domestic hot water (DHW) and conventional heating radiators require high water temperatures, reducing the COP that can be attained, and affecting the choice of heat pump technology.

| Pump type and source | Typical use | 35 °C (e.g. heated screed floor) |

45 °C (e.g. heated screed floor) |

55 °C (e.g. heated timber floor) |

65 °C (e.g. radiator or DHW) |

75 °C (e.g. radiator and DHW) |

85 °C (e.g. radiator and DHW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-efficiency air source heat pump (ASHP), air at −20 °C[24] | 2.2 | 2.0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Two-stage ASHP, air at −20 °C[25] | Low source temperature | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.9 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| High efficiency ASHP, air at 0 °C[24] | Low output temperature | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.0 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Prototype transcritical CO 2 (R744) heat pump with tripartite gas cooler, source at 0 °C[26] |

High output temperature | 3.3 | ‐ | ‐ | 4.2 | ‐ | 3.0 |

| Ground source heat pump (GSHP), water at 0 °C[24] | 5.0 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 2.4 | ‐ | ‐ | |

| GSHP, ground at 10 °C[24] | Low output temperature | 7.2 | 5.0 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 2.4 | ‐ |

| Theoretical Carnot cycle limit, source −20 °C | 5.6 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.4 | |

| Theoretical Carnot cycle limit, source 0 °C | 8.8 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 4.2 | |

| Theoretical Lorentzen cycle limit (CO 2 pump), return fluid 25 °C, source 0 °C[26] |

10.1 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 6.1 | |

| Theoretical Carnot cycle limit, source 10 °C | 12.3 | 9.1 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 |

One observation is that while current "best practice" heat pumps (ground source system, operating between 0 °C and 35 °C) have a typical COP around 4, no better than 5, the maximum achievable is 8.8 because of fundamental Carnot cycle limits. This means that in the coming decades, the energy efficiency of top-end heat pumps could roughly double. Cranking up efficiency requires the development of a better gas compressor, fitting HVAC machines with larger heat exchangers with slower gas flows, and solving internal lubrication problems resulting from slower gas flow. Depending on the working fluid, the expansion stage can be important also. Work done by the expanding fluid cools it and is available to replace some of the input power. (An evaporating liquid is cooled by free expansion through a small hole, but an ideal gas is not.)

Types

Compression vs. absorption

The two main types of heat pumps are compression and absorption. Compression heat pumps operate on mechanical energy (typically driven by electricity), while absorption heat pumps may also run on heat as an energy source (from electricity or burnable fuels).[27] An absorption heat pump may be fueled by natural gas or LP gas, for example. While the gas utilization efficiency in such a device, which is the ratio of the energy supplied to the energy consumed, may average only 1.5, that is better than a natural gas or LP gas furnace, which can only approach 1.

Heat sources and sinks

By definition, all heat sources for a heat pump must be colder in temperature than the space to be heated. Most commonly, heat pumps draw heat from the air (outside or inside air) or from the ground (groundwater or soil).[28]

The heat drawn from ground-sourced systems is in most cases stored solar heat, and it should not be confused with direct geothermal heating, though the latter will contribute in some small measure to all heat in the ground. True geothermal heat, when used for heating, requires a circulation pump but no heat pump, since for this technology the ground temperature is higher than that of the space that is to be heated, so the technology relies only upon simple heat convection.

Other heat sources for heat pumps include water; nearby streams and other natural water bodies have been used, and sometimes domestic waste water (via drain water heat recovery) which is often warmer than cold winter ambient temperatures (though still of lower temperature than the space to be heated).

A number of sources have been used for the heat source for heating private and communal buildings.[29]

Air (ASHP)

- Air source heat pump (extracts heat from outside air)

- Air–air heat pump (transfers heat to inside air)

- Air–water heat pump (transfers heat to a heating circuit and a tank of domestic hot water)

Air-air heat pumps, that extract heat from outside air and transfer this heat to inside air, are the most common type of heat pumps and the cheapest. These are similar to air conditioners operating in reverse. Air-water heat pumps are otherwise similar to air-air heat pumps, but they transfer the extracted heat into a water heating circuit, floor heating being the most efficient, and they can also transfer heat into a domestic hot water tank for use in showers and hot water taps of the building. However, ground-water heat pumps are more efficient than air-water heat pumps, and therefore they are often the better choice for providing heat for the floor heating and domestic hot water systems.

Air source heat pumps are relatively easy and inexpensive to install and have therefore historically been the most widely used heat pump type. However, they suffer limitations due to their use of the outside air as a heat source. The higher temperature differential during periods of extreme cold leads to declining efficiency. In mild weather, COP may be around 4.0, while at temperatures below around 0 °C (32 °F) an air-source heat pump may still achieve a COP of 2.5. The average COP over seasonal variation is typically 2.5-2.8, with exceptional models able to exceed this in mild climates.

In areas where only fossil fuels are available (e.g. heating oil only; no natural gas pipes available) air source heat pumps could be used as an alternative, supplemental heat source to reduce a building's dependence on fossil fuel. Depending on fuel and electricity prices, using the heat pump for heating may be less expensive than using fossil fuel. A backup fossil-fuel, solar hot water or biomass heat source may still be required for the coldest days.

The heating output of low temperature optimized heat pumps (and hence their energy efficiency) still declines dramatically as the temperature drops, but the threshold at which the decline starts is lower than conventional pumps, as shown in the following table (temperatures are approximate and may vary by manufacturer and model):

| Air Source Heat Pump Type | Full heat output at or above this temperature | Heat output down to 60% of maximum at |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional | 47 °F (8.3 °C) | 32 °F (0 °C) |

| Low Temp Optimized | 41 °F ( 5 °C) | 17 °F (-8.3 °C) |

Ground (GSHP)

- Ground source heat pump (extracts heat from the ground or similar sources)

- Ground–air heat pump (transfers heat to inside air)

- Soil–air heat pump (soil as a source of heat)

- Rock–air heat pump (rock as a source of heat)

- Water–air heat pump (body of water as a source of heat, can be groundwater, lake, river etc.)

- Ground–water heat pump (transfers heat to a heating circuit and a tank of domestic hot water)

- Soil–water heat pump (ground as a source of heat)

- Rock–water heat pump (rock as a source of heat)

- Water–water heat pump (body of water as a source of heat)

- Ground–air heat pump (transfers heat to inside air)

Ground-source heat pumps, also called geothermal heat pumps, typically have higher efficiencies than air-source heat pumps. This is because they draw heat from the ground or groundwater which is at a relatively constant temperature all year round below a depth of about 30 feet (9 m).[30] This means that the temperature differential is lower, leading to higher efficiency. Well maintained ground-source heat pumps typically have COPs of 4.0[31] at the beginning of the heating season, with lower seasonal COPs of around 3.0 as heat is drawn from the ground. The tradeoff for this improved performance is that a ground-source heat pump is more expensive to install, due to the need for the drilling of boreholes for vertical placement of heat exchanger piping or the digging of trenches for horizontal placement of the piping that carries the heat exchange fluid (water with a little antifreeze).

When compared, groundwater heat pumps are generally more efficient than heat pumps using heat from the soil. Closed loop soil or ground heat exchangers tend to accumulate cold if the ground loop is undersized. This can be a significant problem if nearby ground water is stagnant or the soil lacks thermal conductivity, and the overall system has been designed to be just big enough to handle a "typical worst case" cold spell, or is simply undersized for the load.[32] One way to fix cold accumulation in the ground heat exchanger loop, is to use ground water to cool the floors of the building on hot days, thereby transferring heat from the dwelling into the ground loop. There are several other methods for replenishing a low temperature ground loop; one way is to make large solar collectors, for instance by putting plastic pipes just under the roof, or by putting coils of black polyethylene pipes under glass on the roof, or by piping the tarmac of the parking lot.[33]

Exhaust air (EAHP)

- Exhaust air heat pump (extracts heat from the exhaust air of a building, requires mechanical ventilation)

- Exhaust air-air heat pump (transfers heat to intake air)

- Exhaust air-water heat pump (transfers heat to a heating circuit and a tank of domestic hot water)

Water source heat pumps (WSHP)

- Uses flowing water as source or sink for heat

- Single-pass vs. recirculation

- Single-pass — water source a body of water or a stream

- Recirculation

- When cooling, closed-loop heat transfer medium to central cooling tower or chiller (typically in a building or industrial setting)

- When heating, closed-loop heat transfer medium from central boilers generating heat from combustion or other sources

Hybrid (HHP)

Hybrid (or twin source) heat pumps: when outdoor air is above 4 to 8 Celsius, (40-50 Fahrenheit, depending on ground water temperature) they use air; when air is colder, they use the ground source. These twin source systems can also store summer heat, by running ground source water through the air exchanger or through the building heater-exchanger, even when the heat pump itself is not running. This has dual advantage: it functions as a low running cost for air cooling, and (if ground water is relatively stagnant) it cranks up the temperature of the ground source, which improves the energy efficiency of the heat pump system by roughly 4% for each degree in temperature rise of the ground source.

Air/water-brine/water heat pump (hybrid heat pump)

The air/water-brine/water heat pump is a hybrid heat pump, developed in Rostock, Germany, that uses only renewable energy sources. Unlike other hybrid systems, which usually combine both conventional and renewable energy sources, it combines air and geothermal heat in one compact device. The air/water-brine/water heat pump has two evaporators — an outside air evaporator and a brine evaporator — both connected to the heat pump cycle. This allows use of the most economical heating source for the current external conditions (for example, air temperature). The unit automatically selects the most efficient operating mode — air or geothermal heat, or both together. The process is controlled by a control unit, which processes the large amounts of data delivered by the complex heating system.

The control unit comprises two controllers, one for the air heat cycle and one for the geothermal circulation, in one device. All components communicate over a common bus to ensure they interact to enhance the efficiency of the hybrid heating system. The German Patent and Trade Mark Office in Munich granted the air/water-brine/water heat pump a patent in 2008, under the title “Heat pump and method for controlling the source inlet temperature to the heat pump”. This hybrid heat pump can be combined with a solar thermal system or with an ice-storage. It trades and is marketed under the name ThermSelect. In the United Kingdom, ThermSelect won the 2013 Commercial Heating Product of the Year award of the HVR Awards for Excellence, organised by Heating and Ventilating Review, an industry magazine.

Heat distribution

Heat pumps are only highly efficient when they generate heat at a low temperature differential, ideally around or below 32 °C (90 °F). Normal steel plate radiators are not practical, because they would need to be four to six times their current size. Underfloor heating is one ideal solution. When wooden floors or carpets would spoil efficiency, wall heaters (plastic pipes covered with a thick layer of chalk) and piped ceilings can be used. These systems have the disadvantage that they are slow starters, and that they would require extensive renovation in existing buildings.

The alternative is a warm air system. Such a setup can either complement slower floor heating during warm up, or it can be a quick and economical way to implement a heat pump system into existing buildings. Oversizing the fans and ductwork can reduce the acoustic noise they produce. To efficiently distribute warm water or air from a heat pump, water pipes or air shafts must have significantly larger diameters than in conventional, hotter-source systems, and underfloor heaters should have much more pipes per square meter.

Solid state heat pumps

Magnetic

In 1881, the German physicist Emil Warburg put a block of iron into a strong magnetic field and found that it increased very slightly in temperature. Some commercial ventures to implement this technology are underway, claiming to cut energy consumption by 40% compared to current domestic refrigerators.[34] The process works as follows: Powdered gadolinium is moved into a magnetic field, heating the material by 2 to 5 °C (4 to 9 °F). The heat is removed by a circulating fluid. The material is then moved out of the magnetic field, reducing its temperature below its starting temperature.

Thermoelectric

Solid state heat pumps using the thermoelectric effect have improved over time to the point where they are useful for certain refrigeration tasks. Thermoelectric (Peltier) heat pumps are generally only around 10-15% as efficient as the ideal refrigerator (Carnot cycle), compared with 40–60% achieved by conventional compression cycle systems (reverse Rankine systems using compression/expansion);[35] however, this area of technology is currently the subject of active research in materials science. A reason why this is popular is because it has a "long lifetime" as there are no moving parts and it does not use potentially hazardous refrigerants.

Thermoacoustic

Near-solid-state heat pumps using thermoacoustics are commonly used in cryogenic laboratories.

Historical development

Milestones:

- 1748: William Cullen demonstrates artificial refrigeration.

- 1834: Jacob Perkins builds a practical refrigerator with diethyl ether.

- 1852: Lord Kelvin describes the theory underlying heat pump.

- 1855–1857: Peter von Rittinger develops and builds the first heat pump.[36]

- 1948: Robert C. Webber is credited as developing and building the first ground heat pump.[37]

See also

References

- ↑ Air-source heat pumps National Renewable Energy Laboratory June 2011

- ↑ http://www.canadiantire.ca/en/home/heating-air-conditioning/baseboard-wall-heaters.html?cid=KWGoogle_Eclipse_Home&gclid=CJaKlLq338oCFQeRfgodap8CQg&gclsrc=aw.ds

- ↑ http://www.heatpumppriceguides.com/#sizes 18000btu/hr

- ↑ https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/buildings_roadmap.pdf pg16

- ↑ http://energy.gov/energysaver/heat-pump-systems

- ↑ http://www.energysavingtrust.org.uk/domestic/air-source-heat-pumps

- ↑ R-410A#Environmental effects

- ↑ Ecometrica.com. "Calculation of green house gas potential of R-410A". Retrieved 2015-07-13.

- ↑ r404a & dme eco-refrigerant blend as a new solution to limit the global warming effect archive 2012.03.14

- ↑ "HEAT PUMPS AND AIR CONDITIONING UNITS, Social Factors, CEN/TC 113 Business Plan, p. 2" (PDF). Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "Mr Slim New Product Information PLA-RP125BA2" (PDF). Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "Hiil innovating Justice "How to determine acceptable levels of noise nuisance (UK)". Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ "Obwieszczenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 15 października 2013 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia jednolitego tekstu rozporządzenia Ministra Środowiska w sprawie dopuszczalnych poziomów hałasu w środowisku, Dz.U. 2014 poz. 112(Polish Ministry of Environment regulation on the publication of Single Noise Level Act for noise levels permitted in environment, 15 October 2014 (in Polish)". Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "Monica S. Hammer, Tracy K. Swinburn, and Richard L. Neitzel "Environmental Noise Pollution in the United States: Developing an Effective Public Health Response" Environmental Health Perspectives V122,I2,2014". Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ "Toshiba Heat Pumps General News on The Super Daiseikai "G2KVP" Series". Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ "American Standard® Heating&Conditioning Heat Pump Product Brochure". Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ "Hannabery HVAC "Commonly Reported HVAC Problems: Outdoor unit makes strange or loud noises"". Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ "Hiil innovating Justice "How to determine acceptable levels of noise nuisance (France)". Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ "Code de la santé publique - Article R1334-33 (in French)". Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Choosing and Installing Geothermal Heat Pumps". Energy.gov. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Lowe, Robert (2011). "Combined heat and power considered as a virtual steam cycle heat pump". Energy Policy 39 (9): 5528–5534. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.05.007. ISSN 0301-4215.

- ↑ Thermal Banks store heat between seasons | Seasonal Heat Storage | Rechargeable Heat Battery | Thermogeology | UTES | Solar recharge of heat batteries

- ↑ BSRIA, "European energy legislation explained", www.bsria.co.uk, May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 The Canadian Renewable Energy Network 'Commercial Earth Energy Systems', Figure 29. . Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ↑ Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences 'State of the Art of Air-source Heat Pump for Cold Region', Figure 5. . Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- 1 2 SINTEF Energy Research 'Integrated CO2 Heat Pump Systems for Space Heating and DHW in low-energy and passive houses', J. Steen, Table 3.1, Table 3.3. . Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ↑ Warmtepompen voor woningverwarming brochure 9-10-2013

- ↑ "Heat pumps sources including groundwater, soil, outside and inside air)" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-02.

- ↑ "Homeowners using heat pump systems" (PDF). United States Department of Energy. September 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on -32 January 2008. Check date values in:

|archive-date=(help) - ↑ Earth Temperature and Site Geology

- ↑ Performance of Ground Source Heat Pumps in Manitoba Rob Andrushuk, Phil Merkel, June 2009

- ↑ Geothermalhelp.com

- ↑ Asphalt Solar Collector Renewable Heat for IHT | Solar Collectors | Solar Recharge for GSHP | Pavement Solar Collectors | Road Solar Thermal Collector

- ↑ Guardian Unlimited, December 2006 'A cool new idea from British scientists: the magnetic fridge'

- ↑ - The Prospects of Alternatives to Vapor Compression Technology for Space Cooling and Food Refrigeration Applications DR Brown, N Fernandez, JA Dirks, TB Stout. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory March 2010

- ↑ Banks, David L. An Introduction to Thermogeology: Ground Source Heating and Cooling (PDF). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-7061-1.

- ↑ "History of Geothermal Technology" Furnace Repair Edmonton, 2014

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heat pumps. |

- Heat pump (engineering) at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Practical information on setting up geothermal heat pump systems at home

- International Energy Agency Heat Pump Programme, Information site for heat pumping technology

|