Heart (symbol)

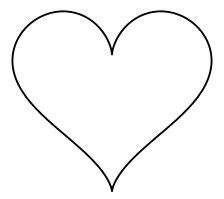

The "heart shape" (♥) is an ideograph used to express the idea of the "heart" in its metaphorical or symbolic sense as the center of emotion, including affection and love, especially (but not exclusively) romantic love.

The "wounded heart" indicating love sickness came to be depicted as a heart symbol pierced with an arrow (Cupid's), or heart symbol "broken" in two or more pieces.

History

Earliest use

The combination of the "heart shape" and its use within the "heart" metaphor developed at the end of the Middle Ages. With possible early examples or direct predecessors in the 13th to 14th century, the familiar symbol of the heart representing love developed in the 15th century, and became widely popular in the 16th.[1] Before the 14th century, the "heart shape" was not associated with the meaning of the "heart" metaphor. The geometric shape itself is found in much earlier sources, but in such instances does not depict a "heart", but typically foliage: in examples from antiquity fig leaves, and in medieval iconography and heraldry typically the leaves of ivy and of the water-lily.

The first known depiction of a heart as a symbol of romantic love dates to the 1250s. It occurs in a miniature decorating a capital S in a manuscript of the French Roman de la poire (National Library FR MS. 2086, plate 12). In the miniature, a kneeling lover (or more precisely, an allegory of the lover's "sweet gaze" or douz regart) offers his heart to a damsel. The heart here resembles a pine-cone (held "upside-down", the point facing downward), in accord with medieval anatomical descriptions.[2] Giotto in his 1305 painting in the Scrovegni Chapel (Padua) shows an allegory of charity handing her heart to Christ, and this heart is depicted in the pine-cone shape based on anatomical descriptions (still held "upside-down"). Giotto's painting exerted considerable influence on later painters, and the motive of Caritas offering a heart is shown by Taddeo Gaddi in Santa Croce, by Andrea Pisano on the bronze door of the south porch of the Baptisterium in Florence (c. 1337), by Ambrogio Lorenzetti in the Palazzo Publico in Siena (c. 1340) and by Andrea da Firenze in Santa Maria Novella in Florence (c. 1365). The convention of showing the heart point-upward switches in the late 14th century and becomes rare in the first half of the 15th century.[2]

The "scalloped" shape of the now-familiar heart symbol, with a dent in its base, first arises in the early 14th century, at first only lightly dented, as in the miniatures in Francesco Barberino's Documenti d'amore (before 1320); a slightly later example with a more pronounced dent is found in a manuscript from the Cistercian monastery in Brussels (MS 4459–70, fol 192v. Royal Library of Belgium). The convention of showing a dent at the base of the heart thus spread at about the same time as the convention of showing the heart with its point downward.[3] The modern indented red heart has been used on playing cards since the late 15th century.[4]

Various hypotheses attempted to connect the "heart shape" as it evolved in the late medieval period with instances of the geometric shape in antiquity.[5] Such theories are modern, proposed from the 1960s onward, and they remain speculative, as no continuity between the supposed ancient predecessors and the late medieval tradition can be shown. Specific suggestions include: the shape of the seed of the silphium plant, used in ancient times as an herbal contraceptive,[5][6] and stylized depictions of features of the human female body, such as the female's buttocks, pubic mound, or spread vulva.[7]

Renaissance and early modern

Hearts can be seen on the bible Jesus holds in the Empress Zoe mosaic in the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. It probably dates from 1239.

Hearts can also be seen on various stucco reliefs and wall panels excavated from the ruins of Ctesiphon, the Persian capital (circa 90 BC – 637 AD).[8][9][10]

The Luther rose was the seal that was designed for Martin Luther at the behest of Prince John Frederick, in 1530, while Luther was staying at the Coburg Fortress during the Diet of Augsburg. Luther wrote an explanation of the symbol to Lazarus Spengler: "a black cross in a heart, which retains its natural color, so that I myself would be reminded that faith in the Crucified saves us. 'For one who believes from the heart will be justified' (Romans 10:10)."[11]

The aorta remains visible, as a protrusion at the top centered between the two "chambers" indicated in the symbol, in some depictions of the Sacred Heart well into the 18th century, and is partly still shown today (although mostly obscured by elements such as a crown, flames, rays, or a cross) but the "hearts" suit did not have this element since the 15th century.

The heart symbol reached Japan with the Nanban trade of 1543 to 1614, as evidenced by an Edo period Samurai helmet (dated c. 1630), which includes both the rounded and indented forms of the heart symbol, representing the heart of Marishiten, goddess of archers.[12]

-

The chanson Belle, Bonne, Sage by Baude Cordier, written in the shape of a heart, in the Chantilly Codex. This is one of two dedicatory pieces placed at the beginning of the older (late 14th century) corpus, probably to replace the original first fascicle, which is missing.

-

Early depiction of the Heart of Jesus in the context of the Five Wounds (the wounded heart here depicting Christ's wound inflicted by the Lance of Longinus) in a 15th-century manuscript (Cologne Mn Kn 28-1181 fol. 116)

-

1486 depiction of the Five Wounds

-

Miniature from the Petit Livre d'Amour (c. 1500), showing the author Pierre Sala depositing his heart in a marguerite flower (symbolizing his mistress, who was called Marguerite). Also worth mentioning is the miniature on fol. 13r, showing two women catching winged hearts in a net.

-

The Luther rose, 1706 print after the 1530 design.

-

Hearts suit in a 1540s German deck of playing cards

-

The Danish "Heart Book", a heart-shaped manuscript of love ballads from the 1550s.

-

Saint Augustine holding a heart in his hand which is set alight by a ray emanating from divine Truth (Veritas), painting by Philippe de Champaigne, ca. 1650.

-

Allegorical painting of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The central heart radiates hearts gathered up by Putti. By Robert la Longe, ca. 1705.

-

Leaden heart of Raesfeld chapel (funerary casket containing the heart of Christoph Otto von Velen, d. 1733)

-

18th-century depiction of the Sacred Heart from the vision of Marguerite Marie Alacoque (d. 1690). The heart is both "heart shaped" and drawn anatomically correct, with both the aorta and the pulmonary artery visible, with the crucifix placed inside the aorta.

-

Another anatomically correct Sacred Heart, painted in c. 1770 by José de Páez.

Modern

Since the 19th century, the symbol has often been used on St. Valentine's Day cards, candy boxes, and similar popular culture artifacts as a symbol of romantic love.

The use of the heart symbol as a logograph for the English verb "to love" derives from the use in "I ♥ NY", introduced in 1977.[13]

Heart symbols were used to symbolize "health" or "lives" in video games; influentially so in The Legend of Zelda (1986). Super Mario Bros. 2 (1987, 1988) did have a "life bar" composed of hexagons, but in 1990s remakes of these games, the hexagons were replaced by heart shapes. Since the 1990s, the heart symbol has also been used as an ideogram indicating "health" outside of the video gaming context, e.g. used by restaurants to indicate "heart-healthy" nutrient content claim (e.g. "low in cholesterol"). A copyrighted "heart-check" symbol to indicate healthy food was introduced by the American Heart Association in 1995.[14]

-

A heart-shaped "Map of Woman's Heart" (1830s)

-

Two burning hearts, coloured pink, illustration on a Victorian-era Valentine's Day card.

-

A "Vinegar Valentine" card from the 1870s, with a red heart symbol pierced by six arrows.

-

The traditional "heart shape" appears on a 1910 Valentine's Day card.

-

Sheet music cover of "Look in His Eyes", from the musical Have a Heart (1913).

Heraldry

The earliest "heart-shaped" charges in heraldry appear in the 12th century; the hearts in the coat of arms of Denmark go back to the royal banner of the kings of Denmark, in turn based on a seal used as early as the 1190s. However, while the charges are clearly "heart-shaped", they did not in origin depict hearts, or symbolize any idea related to "love". Instead, they are assumed to have depicted the leaves of the water-lily. Early heraldic "heart-shaped" charges depicting the leaves of waterlilies are found in various other designs related to territories close to rivers or a coastline (e.g. Flags of Frisia).

Inverted heart symbols have been used in heraldry as stylized testicles (coglioni in Italian) as in the canting arms of the Colleoni family of Milan.[15]

A seal attributed to William, Lord of Douglas (of 1333) shows a heart shape, identified as the heart of Robert the Bruce. The authenticity of this seal is "very questionable",[16] i.e. it could possibly date to the late 14th or the 15th century.[17]

Heraldic charges actually representing hearts become more common in the early modern period, with the Sacred Heart depicted in ecclesiastical heraldry, and hearts representing love in bourgeois coats of arms. Hearts later also become popular elements in municipal coats of arms.

-

.svg.png)

Royal Banner of the Kings of Denmark (12th or 13th century).

-

Coat of arms of the Principality of Lüneburg, originating with William of Winchester, Lord of Lüneburg (d. 1213) who married Helena, daughter of Valdemar I of Denmark, and therefore adopted the "Danish tincture" to the arms of his father, Henry the Lion.[1]

-

14th-century fresco showing Valdemar IV of Denmark. Here the Danish coat of arms is shown without the water-lily leaves ("hearts"), but they are shown on the king's surcoat and on the crest drawn above his shield.

-

Arms of the Earl of Douglas (created 1358, forfeited 1455), and in use in the armorials of all branches of the House of Douglas to the present day.

-

A tomb dated 1693 from southern Germany (Lake Constance region) showing a heart with two arrows as part of the deceased woman's coat of arms

-

Coat of arms of the city of Glinsk, Poltava Governorate (now Sumy Oblast, Ukraine) in the Russian Empire (1782)

-

A heart in a Polish coat of arms, dated to ca. 1750.

-

A heart pierced with an arrow in a Polish coat of arms (recorded 1897)

-

The Sacred Heart in the episcopal coat of arms of Ivan Ljavinec, Apostolic Exarch of the Apostolic Exarchate in the Czech Republic from 1996 to 2003.

- ^ C. Weyers in: Stengel (ed.), Archiv für Diplomatik: Schriftgeschichte, Siegel, und Wappenkunde, Volume 54, 2008, p. 100.

Encoding

A common emoticon for the heart is <3. In Unicode several heart symbols are available:

| Glyph | Description | HTML code | Alt codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ♡ | U+2661 WHITE HEART SUIT | ♡ or ♡ |

|

| ♥ | U+2665 BLACK HEART SUIT | ♥ or ♥ or ♥ |

Alt + 3 |

| ❤ | U+2764 HEAVY BLACK HEART | ❤ |

|

| ❥ | U+2765 ROTATED HEAVY BLACK HEART BULLET | ❥ |

|

| ❣ | U+2763 HEAVY HEART EXCLAMATION MARK ORNAMENT | ❣ |

And from the Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs range associated with emoji:

| Glyph | Description | HTML code |

|---|---|---|

| 🎔 | U+1F394 HEART WITH TIP ON THE LEFT | 🎔 |

| 💑 | U+1F491 COUPLE WITH HEART | 💑 |

| 💓 | U+1F493 BEATING HEART | 💓 |

| 💔 | U+1F494 BROKEN HEART | 💔 |

| 💕 | U+1F495 TWO HEARTS | 💕 |

| 💖 | U+1F496 SPARKLING HEART | 💖 |

| 💗 | U+1F497 GROWING HEART | 💗 |

| 💘 | U+1F498 HEART WITH ARROW | 💘 |

| 💙 | U+1F499 BLUE HEART | 💙 |

| 💚 | U+1F49A GREEN HEART | 💚 |

| 💛 | U+1F49B YELLOW HEART | 💛 |

| 💜 | U+1F49C PURPLE HEART | 💜 |

| 💝 | U+1F49D HEART WITH RIBBON | 💝 |

| 💞 | U+1F49E REVOLVING HEARTS | 💞 |

| 💟 | U+1F49F HEART DECORATION | 💟 |

In Code page 437, the original character set of the IBM PC, the value of 3 (hexadecimal 03) represents the heart symbol. This value is shared with the non-printing ETX control character, which overrides the glyph in many contexts.

The Unicode character of the letter ghan of the Georgian alphabet (ღ) has seen some use as a surrogate "heart symbol" in online communication.

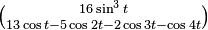

Parametrisation

A number of parametrisations of approximately heart-shaped curves have been described. The best-known of these is the cardioid, which is an epicycloid with one cusp;[18] however, since this lacks the point, it may rather be seen as a stylized water-lily leaf, a so-called seeblatt. Other curves, such as the implicit curve (x2+y2−1)3−x2y3=0, may produce better approximations of the heart shape.[19]

(animated)

(x2 + y2 − 1)3 − x2y3 = 0

-

heart curve on ti-89 graphics calculator

-

parametric equation of heart curve on ti-89 graphics calculator

See also

References

General references

- Martin Kemp, "The Heart" in Christ to Coke: How Image Becomes Icon, Oxford University Press, 2011, 81–113.

- P. J. Vinken (2000), The Shape of the Heart: A Contribution to the Iconology of the Heart (illustrated ed.), Elsevier Health Sciences, ISBN 978-0-444-82987-0

- Vinken, P (2001), "How the heart was held in medieval art", The Lancet 358 (9299): 2155–2157, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07224-5, PMID 11784647

Inline citations

- ↑ Kemp (2011), 96–99.

- 1 2 Vinken (2001).

- ↑ Vinken (2001): "The change from the spherical to the scalloped form of the heart base happened more or less in train with the differing way in which the heart was held, and has dominated visual representations of the heart ever since."

- ↑ A Breef History of Playing Cardes, by Charles Knutson, Renaissance Magazine 2001

- 1 2 The Shape of My Heart: Where did the ubiquitous Valentine's symbol come from? by Keelin McDonell, Slate.com, Tuesday, Feb. 13, 2007.

- ↑ Sowing the seeds of love, The Age, by Luke Benedictus, February 12, 2006; use as contraceptive: Pliny the Elder, XXII, Ch. 49

- ↑ proposed by Gloria Steinem in the 1998 introduction to the Vagina Monologues online copy; "For example, the shape we call a heart—whose symmetry resembles the vulva far more than the asymmetry of the organ that shares its name—is probably a residual female genital symbol. It was reduced from power to romance by centuries of male dominance.", based on an earlier suggestion by Tanzer (1969) that the shape was used as a symbol indicating brothels in ancient Pompeii). Tanzer (1969). The Common People of Pompeii. A study of the graffiti. With illustrations and a map

- ↑ Roundel with radiating palmettes. (n.d.). Retrieved April 7, 2015, from http://metmuseum.org/exhibitions/view?exhibitionId={60853040-AE7E-4162-8FA7-525505D6B633}&oid=322631

- ↑ Fragments of stucco roundels in situ, Taq-i Kisra, south building, Ctesiphon, Iraq, 1931–32. (n.d.). Retrieved April 7, 2015, from http://www.metmuseum.org/met-around-the-world/images/wb_large/wb_Ctesiphon2.jpg

- ↑ "Wall panel with a guinea fowl [Sasanian] (32.150.13)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/32.150.13 (March 2012)

- ↑ gamesmuseum.uwaterloo.ca, i-p-c-s.org antiquemapsandprints.com, obviously more research is needed here.

- ↑ Samurai helmet representing the flaming jewel, by Unkai Mitsuhisa ca 1630, Ann and Gabriel Barbier-Mueller Collection, exhibited at Boston Fine Arts Museum, April–August 2013.

- ↑ "Subsequently the heart symbol became a shorthand for enthusiasm for everything form software to Yorkshire terriers. It was a stamp that validated lifestyles. People could ♥ their grandchildren or line dancing or Buddha." Stephen Amidon, Thomas Amidon, The Sublime Engine: A Biography of the Human Heart (2011), p. 193.

- ↑ "the heart-check mark that began to appear on a wide array of food packaging in 1995. The symbol consists of a heart branded with a bold, efficient check mark. It is copyrighted by the American Heart Association (AHA) which licences it for a nominal fee to companies whose products meet the organization's criteria for saturated fat and cholesterol content." Stephen Amidon, Thomas Amidon, The Sublime Engine: A Biography of the Human Heart (2011), p. 193.

- ↑ Woodward, John and George Burnett (1969). Woodward's a treatise on heraldry, British and foreign, page 203. Originally published 1892, Edinburgh: W. & A. B. Johnson. ISBN 0-7153-4464-1. LCCN 02-20303

- ↑ McAndrew, Scotland's Historic Heraldry, 2006, p. 141

- ↑ McAndrew 2006, p. 213.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Cardioid" from MathWorld.

- ↑ Eric W. Weisstein, "Heart Curve." From MathWorld

- ↑ "Hamid Naderi Yeganeh, "Heart" (November 2014)". American Mathematical Society. November 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Heart |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heart symbols. |

- The Heart Symbol – Origin, History And Significance (essay by cardiologist Armin Dietz)