Health care in Australia

Health care in Australia is provided by both private and government institutions. The federal Minister for Health, currently Sussan Ley, administers national health policy, and state and territory governments administer elements of health care within their jurisdictions, such as the operation of hospitals.

Medicare, administered by the federal government, is the publicly funded universal health care system in Australia which was instituted in 1984. It coexists with a private health system. Medicare is funded partly by a 2% Medicare levy[1] (with exceptions for low-income earners), with the balance being provided by government from general revenue. An additional levy of 1% is imposed on high-income earners without private health insurance. As well as Medicare, there is a separate Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme also funded by the federal government which considerably subsidises a range of prescription medications.

The funding model for health care in Australia has seen political polarisation, with governments being crucial in shaping national health care policy.[2]

Statistics

In 2005/2006 Australia had (on average) 1 doctor per 322 people and 1 hospital bed per 244 people.[3] At the 2011 Australian Census 70,200 medical practitioners (including doctors and specialist medical practitioners) and 257,200 nurses were recorded as currently working.[4]

In a sample of 13 developed countries Australia was eighth in its population weighted usage of medication in 14 classes in 2009 and also in 2013. The drugs studied were selected on the basis that the conditions treated had high incidence, prevalence and/or mortality, caused significant long-term morbidity and incurred high levels of expenditure and significant developments in prevention or treatment had been made in the last 10 years. The study noted considerable difficulties in cross border comparison of medication use.[5]

National health policy

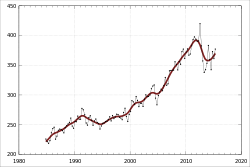

| Financial year | % of GDP | Current price ($ billions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1981–82 | 6.3 | 10.8 |

| 1991–92 | 7.2 | 30.5 |

| 2001–02 | 8.4 | 63.1 |

| 2008–09 | 9.0 | 114.4 |

| 2009–10 | 9.4 | 121.7 |

| 2010–11 | 9.3 | 131.6 |

| 2011–12 | 9.5 | 142.0 |

| 2012–13 | 9.7 | 147.0 |

| 2013–14 | 9.8 | 154.6 |

| Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [6] | ||

Australia has a universal health care structure, with the federal government paying a large part of the cost of health services, including those in public hospitals. The amount paid by the federal government includes:

- patient health costs based on the Medicare benefits schedule. Typically, Medicare covers 75% of general practitioner, 85% of specialist and 100% of public in-hospital costs.

- patients may be entitled to other concessions or benefits[7]

- patients may be entitled to further benefits once they have crossed a so-called safety net threshold, based on total health expenditure for the year.[7]

Government expenditure on healthcare is about 67% of the total, below the OECD average of 72%.[8]

The remainder of health costs (called out of pocket costs or the copayment) are paid by the patient, unless the provider of the service chooses to use bulk billing, charging only the scheduled fee, leaving the patient with no out of pocket costs. Where a particular service is not covered, such as dentistry, optometry, and ambulance transport,[9] patients must pay the full amount, unless they hold a Low Income Earner card, which may entitle them to subsidised access.

Individuals can take out private health insurance to cover out-of-pocket costs, with either a plan that covers just selected services, to a full coverage plan. In practice, a person with private insurance may still be left with out-of-pocket payments, as services in private hospitals often cost more than the insurance payment.

The government encourages individuals with income above a set level to privately insure. This is done by charging these (higher income) individuals a surcharge of 1% to 1.5% of income if they do not take out private health insurance, and a means-tested rebate. This is to encourage individuals who are perceived as able to afford private insurance not to resort to the public health system,[10] even though people with valid private health insurance may still elect to use the public system if they wish.

Insurance

Funding of the health system in Australia is a combination of government funding and private health insurance. Government funding is through the Medicare scheme, which subsidises out-of-hospital medical treatment and funds free universal access to hospital treatment. Medicare is funded by a 2% tax levy on taxpayers with incomes above a threshold amount, with an extra 1% levy on high income earners without private health insurance, and the balance being provided by the government from general revenue.[11]

Private health insurance funds private health and is provided by a number of private health insurance organisations, called health funds. The largest health fund with a 30% market share is Medibank. Medibank was set up to provide competition to private "for-profit" health funds. Although government owned, the fund has operated as a government business enterprise since 2009, operating as a fully commercialised business paying tax and dividends under the same regulatory regime as do all other registered private health funds. Highly regulated regarding the premiums it can set, the fund was designed to put pressure on other health funds to keep premiums at a reasonable level.[12][13] The Coalition Howard Government had announced that Medibank would be sold in a public float if it won the 2007 election,[14] however they were defeated by the Australian Labor Party under Kevin Rudd which had already pledged that it would remain in government ownership. The Coalition under Tony Abbott made the same pledge to privatise Medibank if it won the 2010 election but was again defeated by Labor. Privatisation was again a Coalition policy for the 2013 election, which the Coalition won. However, public perception that privatisation would lead to reduced services and increased costs makes privatising Medibank a "political hard sell."[13]

Some private health insurers are "for profit" enterprises, and some are non-profit organisations such as HCF Health Insurance and CBHS Health Fund. Some have membership restricted to particular groups, some focus on specific regions – like HBF which centres on Western Australia, but the majority have open membership as set out in the PHIAC annual report.[15] Membership to most of these funds is also accessible using a comparison websites or the decision assistance sites. These sites operate on a commission-basis by agreement with their participating health funds and allow consumers to compare policies before joining online.

Most aspects of private health insurance in Australia are regulated by the Private Health Insurance Act 2007. Complaints and reporting of the private health industry is carried out by an independent government agency, the Private Health Insurance Ombudsman.[16] The ombudsman publishes an annual report that outlines the number and nature of complaints per health fund compared to their market share.[17]

The private health system in Australia operates on a "community rating" basis, whereby premiums do not vary solely because of a person's previous medical history, current state of health, or (generally speaking) their age (but see Lifetime Health Cover below).[18] Balancing this are waiting periods, in particular for pre-existing conditions (usually referred to within the industry as PEA, which stands for "pre-existing ailment"). Funds are entitled to impose a waiting period of up to 12 months on benefits for any medical condition the signs and symptoms of which existed during the six months ending on the day the person first took out insurance. They are also entitled to impose a 12-month waiting period for benefits for treatment relating to an obstetric condition, and a 2-month waiting period for all other benefits when a person first takes out private insurance.[18] Funds have the discretion to reduce or remove such waiting periods in individual cases. They are also free not to impose them to begin with, but this would place such a fund at risk of "adverse selection", attracting a disproportionate number of members from other funds, or from the pool of intending members who might otherwise have joined other funds. It would also attract people with existing medical conditions, who might not otherwise have taken out insurance at all because of the denial of benefits for 12 months due to the PEA Rule. The benefits paid out for these conditions would create pressure on premiums for all the fund's members, causing some to drop their membership, which would lead to further rises, and a vicious cycle would ensue.

There are a number of other matters about which funds are not permitted to discriminate between members in terms of premiums, benefits or membership – these include racial origin, religion, sex, sexual orientation, nature of employment, and leisure activities. Premiums for a fund's product that is sold in more than one state can vary from state to state, but not within the same state.

The Australian government has introduced a number of incentives to encourage adults to take out private hospital insurance. These include:

- Lifetime Health Cover: If a person has not taken out private hospital cover by 1 July after their 31st birthday, then when (and if) they do so after this time, their premiums must include a loading of 2% per annum. Thus, a person taking out private cover for the first time at age 40 will pay a 20 per cent loading. The loading continues for 10 years. The loading applies only to premiums for hospital cover, not to ancillary (extras) cover.

- Medicare Levy Surcharge: People whose taxable income is greater than a specified amount (in the 2011/12 financial year $80,000 for singles and $168,000 for couples[19]) and who do not have an adequate level of private hospital cover must pay a 1% surcharge on top of the standard 1.5% Medicare Levy. The rationale is that if the people in this income group are forced to pay more money one way or another, most would choose to purchase hospital insurance with it, with the possibility of a benefit in the event that they need private hospital treatment – rather than pay it in the form of extra tax as well as having to meet their own private hospital costs.

- The Australian government announced in May 2008 that it proposes to increase the thresholds, to $100,000 for singles and $150,000 for families. These changes require legislative approval. A bill to change the law has been introduced but was not passed by the Senate. A changed version was passed on 16 October 2008. There have been criticisms that the changes will cause many people to drop their private health insurance, causing a further burden on the public hospital system, and a rise in premiums for those who stay with the private system. Other commentators believe the effect will be minimal.[20]

- Private Health Insurance Rebate: The government subsidises the premiums for all private health insurance cover, including hospital and ancillary (extras), by 10%, 20% or 30%. In May 2009, The Labor Government under Kevin Rudd announced that as of June 2010, the Rebate would become means-tested and offered on a sliding scale.

Programs and bodies

Federal initiatives

Medicare Australia is responsible for administering Medicare, which provides subsidies for health services. It is primarily concerned with the payment of doctors and nursing staff, and the financing of state-run hospitals.

The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme provides subsidised medications to patients. The level of subsidy depends on the above noted tests. Low income earners may receive a card that entitles the holder to cheaper medicines under the PBS. A National Immunisation Program Schedule that provides many immunisations free of charge by the federal government, the Australian Organ Donor Register, a national register which registers those who elect to be organ donors. Registration is voluntary in Australia and is commonly recorded on a driver's licence or proof of age card are also managed by the federal government.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration is the regulatory body for medicines and medical devices in Australia. At the borders the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service is responsible for maintaining a favourable health status by minimising risk from goods and people entering the country.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) is Australia's national agency for health and welfare statistics and information. Its biennial publication Australia's Health is a key national information resource in the area of health care. The Institute publishes over 140 reports each year on various aspects of Australia's health and welfare. The Food Standards Australia New Zealand and Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency also play a role in protecting and improving the health of Australians.[21]

State programmes

Public Hospitals Each state is responsible for the operation of public hospitals.

Healthcare Initiatives State based projects are regularly set up to target specific problems such as breast cancer screening programs, indigenous youth health programs or school dental health

Non-government organisations

The Australian Red Cross Blood Service collects blood donations and provides them to Australian Healthcare Providers. Other health services such as Medical imaging (MRI and so on) are often provided by private corporations, but patients can still claim from the government if they are covered by the Medicare Benefits Schedule. The National Health and Medical Research Council funds public health research as well as develops statements on policy issues.[21]

Issues

Workforce

In a report published by HealthWorkforce Australia in March 2012, a shortage of nearly 3,000 doctors, over 100,000 nurses and more than 80,000 registered nurses was predicted in the year 2025. In the conclusion of the report, the HWA explains: "For nurses, given the size of the projected workforce shortages presented in this report, HWA will conduct an economic analysis to quantify the cost to allow an assessment of the relative affordability of the modelled scenarios to close the projected gap." Governments, Higher Education and Training, Professions and Employers are also identified as key players in the process of addressing future challenges.[22]

Quality of care

In an international comparative study of the health care systems in six countries (Australia, Canada, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States), found that "Australia ranks highest on healthy lives, scoring first or second on all of the indicators", although its overall ranking in the study was below the UK and Germany systems, tied with New Zealand's and above those of Canada and far above the U.S.[23][24]

A global study of end of life care, conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit, part of the group which publishes The Economist magazine, published the compared end of life care, gave the highest ratings to Australia and the UK out of the 40 countries studied, the two country's systems receiving a rating of 7.9 out of 10 in an analysis of access to services, quality of care and public awareness.[25]

Rural and Remote Health Care

Health care services, their availability and the health outcomes of those who live in rural and remote parts of Australia can differ greatly from metropolitan areas. In recent reports, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare noted that "compared with those in Major Cities, people in regional and remote areas were less likely to report very good or excellent health"[6], with life expectancy decreasing with increasing remoteness: "[c]ompared with Major Cities, the life expectancy in regional areas is 1–2 years lower and in remote areas is up to 7 years lower."[7] It was also noted that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experienced worse health than non-Indigenous Australians.[8]

Initiatives

- DisabilityCare Australia

- Healthdirect – Healthdirect provides easy access to trusted, quality health information. Healthdirect is funded by the Australian Governments.[26]

- DoctorConnect – To encourage overseas doctors to work in Australia.[27]

- HealthcareLink – Australia's first healthcare and medical job board was created to eliminate the challenges faced by many Australian healthcare employers and employees in both sourcing quality candidates and finding suitable job opportunity.[28]

Peak bodies

See also

- Australian paradox

- Emergency medical services in Australia

- Euthanasia in Australia

- Health care compared

- Health care systems

- Medical education in Australia

- Nursing in Australia

- Paramedics in Australia

References

- ↑ https://www.ato.gov.au/Individuals/Medicare-levy/

- ↑ Behan, Pamela (2007). Solving the Health Care Problem: How Other Nations Have Succeeded and Why The United States Has Not. SUNY Press. p. 53. ISBN 0791468380. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ↑ "Britannica World Data, Australia". 2009 Book of the Year. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2009. pp. 516–517. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ↑ "Doctors and Nurses". 4102.0 – Australian Social Trends, April 2013. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 24 July 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ Office of health Economics. "International Comparison of Medicines Usage: Quantitative Analysis" (PDF). Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ↑ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Expenditure data. Retrieved on 10 July 2012.

- 1 2 Thresholds and Concession Calculated Amounts. Medicare Australia.

- ↑ Britnell, Mark (2015). In Search of the Perfect Health System. London: Palgrave. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-137-49661-4.

- ↑ Examples of Services Not Covered by Medicare. Medicare Australia.

- ↑ "Medicare Levy Surcharge". Private Health Insurance Ombudsman. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Australian Health Care System: The national healthcare funding system". The Medicare Levy. Australian Department of Health and Aging. 4 February 2005. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Opposition plans to sell Medibank Private". ABC News. 21 February 2010. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- 1 2 Reece, Nicholas (16 February 2013). "Hanging on to Medibank is a national health hazard". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ↑ Ben Packham (13 September 2006). "Election fight over $2b Medibank plan". The Herald Sun (News Limited). Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ↑ Private Health Insurance Administration Council, Annual Report 2009-10 (PDF), Private Health Insurance Administration Council, retrieved 18 March 2012

- ↑ Private Health Insurance Ombudsman (PHIO)

- ↑ PHIO's Annual Reports

- 1 2 Private Health Insurance in Australia

- ↑ Medicare Levy Surcharge. Private Health Insurance Ombudsmen. Retrieved on 10 July 2012.

- ↑ Medicare levy surcharge effect 'trivial': inquiry ABC News. 12 August 2008.

- 1 2 Louise Fleming, Mary; Elizabeth Anne Parker (2011). Introduction to Public Health. Elsevier Australia. pp. 16–17. ISBN 072954091X. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "Health Workforce 2025 Doctors, Nurses and Midwives – Volume 1" (PDF). HealthWorkforce Australia. Health Workforce 2025 – Doctors, Nurses and Midwives. March 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ rnational_update_final.pdf Figure 2. Six Nation Summary Scores on Health System Performance

- ↑ Davis, Karen; Cathy Schoen; et al. (May 2007). l_update_final.pdf "MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL: AN INTERNATIONAL UPDATE ON THE COMPARATIVE PERFORMANCE OF AMERICAN HEALTH CARE" Check

|url= - ↑ UK comes top on end of life care – report

- ↑ Healthdirect

- ↑ DoctorConnect

- ↑ HealthcareLink

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||