Health system

A health system, also sometimes referred to as health care system or healthcare system, is the organization of people, institutions, and resources that deliver health care services to meet the health needs of target populations.

There is a wide variety of health systems around the world, with as many histories and organizational structures as there are nations. Implicitly, nations must design and develop health systems in accordance with their needs and resources, although common elements in virtually all health systems are primary healthcare and public health measures.[1] In some countries, health system planning is distributed among market participants. In others, there is a concerted effort among governments, trade unions, charities, religious organizations, or other co-ordinated bodies to deliver planned health care services targeted to the populations they serve. However, health care planning has been described as often evolutionary rather than revolutionary.[2][3]

Goals

The World Health Organization (WHO), the directing and coordinating authority for health within the United Nations system, is promoting a goal of universal health care: to ensure that all people obtain the health services they need without suffering financial hardship when paying for them. According to WHO, healthcare systems' goals are good health for the citizens, responsiveness to the expectations of the population, and fair means of funding operations. Progress towards them depends on how systems carry out four vital functions: provision of health care services, resource generation, financing, and stewardship.[4] Other dimensions for the evaluation of health systems include quality, efficiency, acceptability, and equity.[2] They have also been described in the United States as "the five C's": Cost, Coverage, Consistency, Complexity, and Chronic Illness.[5] Also, continuity of health care is a major goal.[6]

Definitions

Often health system has been defined with a reductionist perspective, for example reducing it to healthcare system. In many publications, for example, both expressions are used interchangeably. Some authors[7] have developed arguments to expand the concept of health systems, indicating additional dimensions that should be considered:

- Health systems should not be expressed in terms of their components only, but also of their interrelationships;

- Health systems should include not only the institutional or supply side of the health system, but also the population;

- Health systems must be seen in terms of their goals, which include not only health improvement, but also equity, responsiveness to legitimate expectations, respect of dignity, and fair financing, among others;

- Health systems must also be defined in terms of their functions, including the direct provision of services, whether they are medical or public health services, but also "other enabling functions, such as stewardship, financing, and resource generation, including what is probably the most complex of all challenges, the health workforce."[7]

World Health Organization definition

The World Health Organization defines health systems as follows:

A health system consists of all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore or maintain health. This includes efforts to influence determinants of health as well as more direct health-improving activities. A health system is therefore more than the pyramid of publicly owned facilities that deliver personal health services. It includes, for example, a mother caring for a sick child at home; private providers; behaviour change programmes; vector-control campaigns; health insurance organizations; occupational health and safety legislation. It includes inter-sectoral action by health staff, for example, encouraging the ministry of education to promote female education, a well known determinant of better health.[8]

Providers

Healthcare providers are institutions or individuals providing healthcare services. Individuals including health professionals and allied health professions can be self-employed or working as an employee in a hospital, clinic, or other health care institution, whether government operated, private for-profit, or private not-for-profit (e.g. non-governmental organization). They may also work outside of direct patient care such as in a government health department or other agency, medical laboratory, or health training institution. Examples of health workers are doctors, nurses, midwives, dietitians, paramedics, dentists, medical laboratory technologists, therapists, psychologists, pharmacists, chiropractors, optometrists, community health workers, traditional medicine practitioners, and others.

Financial resources

Aug2005.jpg)

There are generally five primary methods of funding health systems:[9]

- general taxation to the state, county or municipality

- social health insurance

- voluntary or private health insurance

- out-of-pocket payments

- donations to charities

Most countries' systems feature a mix of all five models. One study [10] based on data from the OECD concluded that all types of health care finance "are compatible with" an efficient health system. The study also found no relationship between financing and cost control.

The term health insurance is generally used to describe a form of insurance that pays for medical expenses. It is sometimes used more broadly to include insurance covering disability or long-term nursing or custodial care needs. It may be provided through a social insurance program, or from private insurance companies. It may be obtained on a group basis (e.g., by a firm to cover its employees) or purchased by individual consumers. In each case premiums or taxes protect the insured from high or unexpected health care expenses.

By estimating the overall cost of health care expenses, a routine finance structure (such as a monthly premium or annual tax) can be developed, ensuring that money is available to pay for the health care benefits specified in the insurance agreement. The benefit is typically administered by a government agency, a non-profit health fund or a corporation operating seeking to make a profit.[11]

Many forms of commercial health insurance control their costs by restricting the benefits that are paid by through deductibles, co-payments, coinsurance, policy exclusions, and total coverage limits and will severely restrict or refuse coverage of pre-existing conditions. Many government schemes also have co-payment schemes but exclusions are rare because of political pressure. The larger insurance schemes may also negotiate fees with providers.

Many forms of social insurance schemes control their costs by using the bargaining power of their community they represent to control costs in the health care delivery system. For example, by negotiating drug prices directly with pharmaceutical companies negotiating standard fees with the medical profession, or reducing unnecessary health care costs. Social schemes sometimes feature contributions related to earnings as part of a scheme to deliver universal health care, which may or may not also involve the use of commercial and non-commercial insurers. Essentially the more wealthy pay proportionately more into the scheme to cover the needs of the relatively poor who therefore contribute proportionately less. There are usually caps on the contributions of the wealthy and minimum payments that must be made by the insured (often in the form of a minimum contribution, similar to a deductible in commercial insurance models).

In addition to these traditional health care financing methods, some lower income countries and development partners are also implementing non-traditional or innovative financing mechanisms for scaling up delivery and sustainability of health care,[12] such as micro-contributions, public-private partnerships, and market-based financial transaction taxes. For example, as of June 2011, UNITAID had collected more than one billion dollars from 29 member countries, including several from Africa, through an air ticket solidarity levy to expand access to care and treatment for HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria in 94 countries.[13]

Payment models

In most countries, wage costs for healthcare practitioners are estimated to represent between 65% and 80% of renewable health system expenditures.[14][15] There are three ways to pay medical practitioners: fee for service, capitation, and salary. There has been growing interest in blending elements of these systems.[16]

Fee-for-service

Fee-for-service arrangements pay general practitioners (GPs) based on the service.[16] They are even more widely used for specialists working in ambulatory care.[16]

There are two ways to set fee levels:[16]

- By individual practitioners.

- Central negotiations (as in Japan, Germany, Canada and in France) or hybrid model (such as in Australia, France's sector 2, and New Zealand) where GPs can charge extra fees on top of standardized patient reimbursement rates.

Capitation

In capitation payment systems, GPs are paid for each patient on their "list", usually with adjustments for factors such as age and gender.[16] According to OECD, "these systems are used in Italy (with some fees), in all four countries of the United Kingdom (with some fees and allowances for specific services), Austria (with fees for specific services), Denmark (one third of income with remainder fee for service), Ireland (since 1989), the Netherlands (fee-for-service for privately insured patients and public employees) and Sweden (from 1994). Capitation payments have become more frequent in "managed care" environments in the United States."[16]

According to OECD, "Capitation systems allow funders to control the overall level of primary health expenditures, and the allocation of funding among GPs is determined by patient registrations. However, under this approach, GPs may register too many patients and under-serve them, select the better risks and refer on patients who could have been treated by the GP directly. Freedom of consumer choice over doctors, coupled with the principle of "money following the patient" may moderate some of these risks. Aside from selection, these problems are likely to be less marked than under salary-type arrangements."[16]

Salary arrangements

In several OECD countries, general practitioners (GPs) are employed on salaries for the government.[16] According to OECD, "Salary arrangements allow funders to control primary care costs directly; however, they may lead to under-provision of services (to ease workloads), excessive referrals to secondary providers and lack of attention to the preferences of patients."[16] There has been movement away from this system.[16]

Information resources

Sound information plays an increasingly critical role in the delivery of modern health care and efficiency of health systems. Health informatics – the intersection of information science, medicine and healthcare – deals with the resources, devices, and methods required to optimize the acquisition and use of information in health and biomedicine. Necessary tools for proper health information coding and management include clinical guidelines, formal medical terminologies, and computers and other information and communication technologies. The kinds of data processed may include patients' medical records, hospital administration and clinical functions, and human resources information.

The use of health information lies at the root of evidence-based policy and evidence-based management in health care. Increasingly, information and communication technologies are being utilised to improve health systems in developing countries through: the standardisation of health information; computer-aided diagnosis and treatment monitoring; informing population groups on health and treatment.[17]

Management

The management of any health system is typically directed through a set of policies and plans adopted by government, private sector business and other groups in areas such as personal healthcare delivery and financing, pharmaceuticals, health human resources, and public health.

Public health is concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based on population health analysis. The population in question can be as small as a handful of people, or as large as all the inhabitants of several continents (for instance, in the case of a pandemic). Public health is typically divided into epidemiology, biostatistics and health services. Environmental, social, behavioral, and occupational health are also important subfields.

Today, most governments recognize the importance of public health programs in reducing the incidence of disease, disability, the effects of ageing and health inequities, although public health generally receives significantly less government funding compared with medicine. For example, most countries have a vaccination policy, supporting public health programs in providing vaccinations to promote health. Vaccinations are voluntary in some countries and mandatory in some countries. Some governments pay all or part of the costs for vaccines in a national vaccination schedule.

The rapid emergence of many chronic diseases, which require costly long-term care and treatment, is making many health managers and policy makers re-examine their healthcare delivery practices. An important health issue facing the world currently is HIV/AIDS.[18] Another major public health concern is diabetes.[19] In 2006, according to the World Health Organization, at least 171 million people worldwide suffered from diabetes. Its incidence is increasing rapidly, and it is estimated that by the year 2030, this number will double. A controversial aspect of public health is the control of tobacco smoking, linked to cancer and other chronic illnesses.[20]

Antibiotic resistance is another major concern, leading to the reemergence of diseases such as tuberculosis. The World Health Organization, for its World Health Day 2011 campaign, is calling for intensified global commitment to safeguard antibiotics and other antimicrobial medicines for future generations.

Health systems performance

Since 2000, more and more initiatives have been taken at the international and national levels in order to strengthen national health systems as the core components of the global health system. Having this scope in mind, it is essential to have a clear, and unrestricted, vision of national health systems that might generate further progresses in global health. The elaboration and the selection of performance indicators are indeed both highly dependent on the conceptual framework adopted for the evaluation of the health systems performances.[22] Like most social systems, health systems are complex adaptive systems where change does not necessarily follow rigid epidemiological models. In complex systems path dependency, emergent properties and other non-linear patterns are under-explored and unmeasured,[23] which can lead to the development of inappropriate guidelines for developing responsive health systems.[24]

An increasing number of tools and guidelines are being published by international agencies and development partners to assist health system decision-makers to monitor and assess health systems strengthening[26] including human resources development[27] using standard definitions, indicators and measures. In response to a series of papers published in 2012 by members of the World Health Organization's Task Force on Developing Health Systems Guidance, researchers from the Future Health Systems consortium argue that there is insufficient focus on the 'policy implementation gap'. Recognizing the diversity of stakeholders and complexity of health systems is crucial to ensure that evidence-based guidelines are tested with requisite humility and without a rigid adherence to models dominated by a limited number of disciplines.[24][28]

Health Policy and Systems Research (HPSR) is an emerging multidisciplinary field that challenges 'disciplinary capture' by dominant health research traditions, arguing that these traditions generate premature and inappropriately narrow definitions that impede rather than enhance health systems strengthening.[29] HPSR focuses on low- and middle-income countries and draws on the relativist social science paradigm which recognises that all phenomena are constructed through human behaviour and interpretation. In using this approach, HPSR offers insight into health systems by generating a complex understanding of context in order to enhance health policy learning.[30] HPSR calls for greater involvement of local actors, including policy makers, civil society and researchers, in decisions that are made around funding health policy research and health systems strengthening.[31]

International comparisons

Health systems can vary substantially from country to country, and in the last few years, comparisons have been made on an international basis. The World Health Organization, in its World Health Report 2000, provided a ranking of health systems around the world according to criteria of the overall level and distribution of health in the populations, and the responsiveness and fair financing of health care services.[4] The goals for health systems, according to the WHO's World Health Report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance (WHO, 2000),[32] are good health, responsiveness to the expectations of the population, and fair financial contribution. There have been several debates around the results of this WHO exercise,[33] and especially based on the country ranking linked to it,[34] insofar as it appeared to depend mostly on the choice of the retained indicators.

Direct comparisons of health statistics across nations are complex. The Commonwealth Fund, in its annual survey, "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall", compares the performance of the health systems in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Germany, Canada and the U.S. Its 2007 study found that, although the U.S. system is the most expensive, it consistently underperforms compared to the other countries.[35] A major difference between the U.S. and the other countries in the study is that the U.S. is the only country without universal health care. The OECD also collects comparative statistics, and has published brief country profiles.[36][37][38] Health Consumer Powerhouse makes comparisons between both national health care systems in the Euro health consumer index and specific areas of health care such as diabetes [39] or hepatitis.[40]

| Country | Life expectancy | Infant mortality rate[41] | Preventable deaths per 100,000 people in 2007[42] | Physicians per 1000 people | Nurses per 1000 people | Per capita expenditure on health (USD PPP) | Healthcare costs as a percent of GDP | % of government revenue spent on health | % of health costs paid by government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 81.4 | 4.49 | 57 | 2.8 | 10.1 | 3,353 | 8.5 | 17.7 | 67.5 |

| Canada | 81.4 | 4.78 | 77[43] | 2.2 | 9.0 | 3,844 | 10.0 | 16.7 | 70.2 |

| France | 81.0 | 3.34 | 55 | 3.3 | 7.7 | 3,679 | 11.0 | 14.2 | 78.3 |

| Germany | 79.8 | 3.48 | 76 | 3.5 | 10.5 | 3,724 | 10.4 | 17.6 | 76.4 |

| Italy | 82.1 | 3.33 | 60 | 4.2 | 6.1 | 2,771 | 8.7 | 14.1 | 76.6 |

| Japan | 82.6 | 2.17 | 61 | 2.1 | 9.4 | 2,750 | 8.2 | 16.8 | 80.4 |

| Norway | 80.0 | 3.47 | 64 | 3.8 | 16.2 | 4,885 | 8.9 | 17.9 | 84.1 |

| Sweden | 81.0 | 2.73 | 61 | 3.6 | 10.8 | 3,432 | 8.9 | 13.6 | 81.4 |

| UK | 80.1 | 4.5 | 83 | 2.5 | 9.5 | 3,051 | 8.4 | 15.8 | 81.3 |

| USA | 78.1 | 5.9 | 96 | 2.4 | 10.6 | 7,437 | 16.0 | 18.5 | 45.1 |

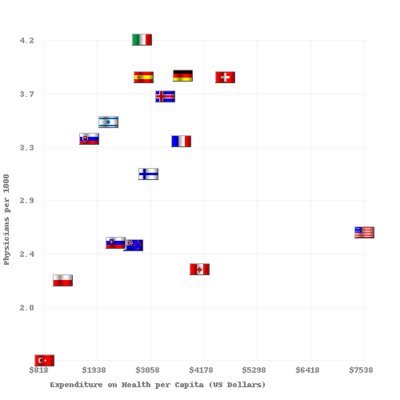

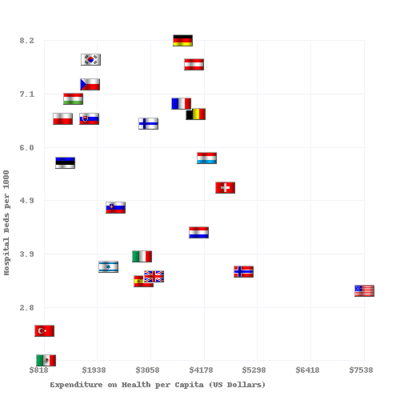

Physicians and hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants vs Health Care Spending in 2008 for OECD Countries. The data source is http://www.oecd.org.[37][38]

See also

- Acronyms in healthcare

- Catholic Church and health care

- Community health

- Comparison of the health care systems in Canada and the United States

- Consumer-driven health care

- Cultural competence in health care

- Global health

- Health administration

- Health care

- Health care provider

- Health care reform

- Health crisis

- Health economics

- Health human resources

- Health insurance

- Health policy

- Health services research

- Healthy city

- Medicine

- National health insurance

- Occupational safety and health

- Philosophy of healthcare

- Primary care

- Primary health care

- Public health

- Publicly funded health care

- Single-payer health care

- Social determinants of health

- Socialized medicine

- Two-tier health care

- Universal health care

References

- ↑ White F. Primary health care and public health: foundations of universal health systems. Med Princ Pract 2015;24:103-116. doi:10.1159/000370197

- 1 2 "Health care system". Liverpool-ha.org.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ New Yorker magazine article: "Getting there from here." 26 January 2009

- 1 2 World Health Organization. (2000). World Health Report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance. Geneva, WHO http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/index.html

- ↑ Remarks by Johns Hopkins University President William Brody: "Health Care '08: What's Promised/What's Possible?" 7 September 2007

- ↑ Cook, R. I.; Render, M.; Woods, D. (2000). "Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety". BMJ 320 (7237): 791–794. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7237.791. PMC 1117777. PMID 10720370.

- 1 2 Frenk J, The Global Health System : strengthening national health systems as the next step for global progress, Plos Medicine, January 2010, Vol 7, issue 1, 3pp., available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2797599/

- ↑ "Everybody's business. Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes : WHO's framework for action" (PDF). WHO. 2007.

- ↑ "Regional Overview of Social Health Insurance in South-East Asia, World Health Organization. And . Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- ↑ Glied, Sherry A. "Health Care Financing, Efficiency, and Equity." National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2008. Accessed 20 March 2008.

- ↑ How Private Insurance Works: A Primer by Gary Claxton, Institution for Health Care Research and Policy, Georgetown University, on behalf of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

- ↑ Bloom, G; et al. (2008). "Markets, Information Asymmetry And Health Care: Towards New Social Contracts". Social Science and Medicine 66 (10): 2076–2087. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.034. PMID 18316147. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ UNITAID. Republic of Guinea Introduces Air Solidarity Levy to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria. Geneva, 30 June 2011. Accessed 5 July 2011.

- ↑ Saltman RB, Von Otter C. Implementing Planned Markets in Health Care: Balancing Social and Economic Responsibility. Buckingham: Open University Press 1995.

- ↑ Kolehamainen-Aiken RL. Decentralization and human resources: implications and impact. Human Resources for Health Development 1997, 2(1):1–14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Elizabeth Docteur and Howard Oxley (2003). "Health-Care Systems: Lessons from the Reform Experience" (PDF). OECD.

- ↑ Lucas, H (2008). "Information And Communications Technology For Future Health Systems In Developing Countries". Social Science and Medicine 66 (10): 2122–2132. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.033. PMID 18343005. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ "European Union Public Health Information System – HIV/Aides page". Euphix.org. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "European Union Public Health Information System – Diabetes page". Euphix.org. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "European Union Public Health Information System – Smoking Behaviors page". Euphix.org. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "OECD.StatExtracts, Health, Non-Medical Determinants of Health, Body weight, Overweight or obese population, self-reported and measured, Total population" (Online Statistics). http://stats.oecd.org/. OECD's iLibrary. 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Handler A, Issel M, Turnock B. A conceptual framework to measure performance of the public health system. American Journal of Public Health, 2001, 91(8): 1235–39.

- ↑ Paina, Ligia; David Peters (5 August 2011). "Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems". Health Policy and Planning 26 (5): 365. doi:10.1093/heapol/czr054. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- 1 2 Peters, David; Sara Bennet (2012). "Better Guidance Is Welcome, but without Blinders". PLoS Med 9 (3): e1001188. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001188. PMC 3308928. PMID 22448148. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ↑ "OECD.StatExtracts, Health, Non-Medical Determinants of Health, Body weight, Obese population, self-reported and measured, Total population" (Online Statistics). http://stats.oecd.org/. OECD's iLibrary. 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ World Health Organization. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva, WHO Press, 2010.

- ↑ Dal Poz MR et al. Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health. Geneva, WHO Press, 2009

- ↑ Hyder, A; et al. (2007). "Exploring health systems research and its influence on policy processes in low income countries". BMC Public Health 7: 309. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-309. PMC 2213669. PMID 17974000. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ↑ Sheikh, Kabir; Lucy Gilson; Irene Akua Agyepong; Kara Hanson; Freddie Ssengooba; Sara Bennett (2011). "Building the Field of Health Policy and Systems Research: Framing the Questions". PLoS Medicine 8 (8): e1001073. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001073. PMC 3156683. PMID 21857809. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ Gilson, Lucy; Kara Hanson; Kabir Sheikh; Irene Akua Agyepong; Freddie Ssengooba; Sara Bennet (2011). "Building the Field of Health Policy and Systems Research: Social Science Matters". PLoS Medicine 8 (8): e1001079. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001079. PMC 3160340. PMID 21886488. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ Bennet, Sara; Irene Akua Agyepong; Kabir Sheikh; Kara Hanson; Freddie Ssengooba; Lucy Gilson (2011). "Building the Field of Health Policy and Systems Research: An Agenda for Action". PLoS 8 (8): e1001081. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001081. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2000) World Health Report 2000 – Health systems: improving performance. Geneva, WHO Press.

- ↑ World Health Organization. Health Systems Performance: Overall Framework. Accessed 15 March 2011.

- ↑ Navarro V. Assessment of the World Health Report 2000. Lancet 2000; 356: 1598–601

- ↑ "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International Update on the Comparative Performance of American Health Care". The Commonwealth Fund. 15 May 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ↑ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. "OECD Health Data 2008: How Does Canada Compare" (PDF). Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- 1 2 "Updated statistics from a 2009 report". Oecd.org. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 "OECD Health Data 2009 – Frequently Requested Data". Oecd.org. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Euro Consumer Diabetes Index 2008". Health Consumer Powerhouse. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "Euro Hepatitis Care Index 2012". Health Consumer Powerhouse. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ CIA – The World Factbook: Infant Mortality Rate. Archived from the original on 18 December 2012 (Older data). Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "Mortality amenable to health care" Nolte, Ellen. "Variations in Amenable Mortality—Trends in 16 High-Income Nations". Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ↑ data for 2003

Nolte, Ellen. "Measuring the Health of Nations: Updating an Earlier Analysis". Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

Further reading

| Library resources about Health system |

- Morrisey, Michael A. (2008). "Health Care". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

External links

- World Health Organization: Health Systems

- HRC/Eldis Health Systems Resource Guide research and other resources on health systems in developing countries

- OECD: Health policies, a list of latest publications by OECD

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|