Health care finance in the United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Healthcare reform in the United States of America |

|---|

|

|

|

Third-party payment models |

| United States portal |

Health care spending in the United States is characterized as the most costly compared to all OECD (developed) countries, measured both per person and as a share of GDP.[1] Despite this spending, the quality of health care overall is low by some measures.[2]

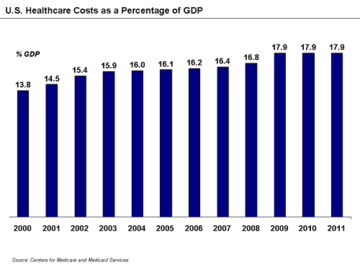

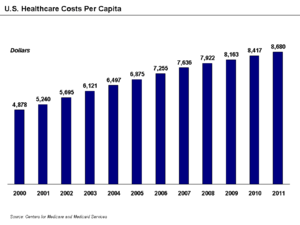

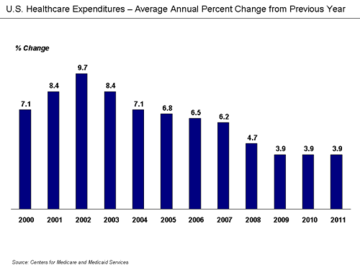

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid reported in 2014 that U.S. healthcare costs were 17.4% GDP in 2013, similar to 2009-2012 but up from 13.4% GDP in 2000. Healthcare costs per capita have risen steadily from $4,881 in 2000 to $9,255 in 2013, a 5% average annual increase. The annual rate of increase in total healthcare costs has been declining, falling steadily from a 9.6% increase in 2002 to 3.8% for 2009 and has been steady since, to a 3.6% increase in 2013.[3]

The Congressional Budget Office reported in January 2015 that Medicare costs were 3.5% GDP in 2014, steady from 2009 but up from 2.1% GDP in 2000. Medicaid costs were 1.7% GDP in 2014, steady from 2009 but up from 1.2% GDP in 2000.[4] CBO projected in June 2015 that federal spending on healthcare programs will rise from 5.2% GDP in 2015 to 8.0% GDP by 2040. This would be driven by a significant increase in the number of program beneficiaries due to the retirement of the Baby Boomers and expanded coverage under the Affordable Care Act, along with healthcare cost inflation.[5]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), total health care spending in the U.S. was 17% of its GDP in 2012, the highest in the world.[6] The Health and Human Services Department expects that the health share of GDP will continue its historical upward trend, reaching 19.6% of GDP by 2024.[7][8] Of each dollar spent on health care in the United States, 31% goes to hospital care, 21% goes to physician/clinical services, 10% to pharmaceuticals, 4% to dental, 6% to nursing homes and 3% to home health care, 3% for other retail products, 3% for government public health activities, 7% to administrative costs, 7% to investment, and 6% to other professional services (physical therapists, optometrists, etc.).[9] The Commonwealth Fund ranked the United States last in the quality of health care among similar countries,[10] and notes U.S. care costs the most.[11]

Around 84.7% of Americans have some form of health insurance; either through their employer or the employer of their spouse or parent (59.3%), purchased individually (8.9%), or provided by government programs (27.8%; there is some overlap in these figures).[12] All government health care programs have restricted eligibility, and there is no government health insurance company which covers all Americans. Americans without health insurance coverage in 2007 totaled 15.3% of the population, or 45.7 million people.[12]

Among those whose employer pays for health insurance, the employee may be required to contribute part of the cost of this insurance, while the employer usually chooses the insurance company and, for large groups, negotiates with the insurance company. Government programs directly cover 27.8% of the population (83 million),[12] including the elderly, disabled, children, veterans, and some of the poor, and federal law mandates public access to emergency services regardless of ability to pay. Public spending accounts for between 45% and 56.1% of U.S. health care spending.[13]

Some Americans do not qualify for government-provided health insurance, are not provided health insurance by an employer, and are unable to afford, cannot qualify for, or choose not to purchase, private health insurance. When charity or "uncompensated" care is not available, they sometimes simply go without needed medical treatment. This problem has become a source of considerable political controversy on a national level.

Spending

As percentage of GDP

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid reported in 2014 that U.S. healthcare costs were 17.4% GDP in 2013, flat since 2009 but up from 13.4% GDP in 2000.[3] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), total health care spending in the U.S. was 17% of its GDP in 2012, the highest in the world.[6] The Health and Human Services Department expects that the health share of GDP will continue its historical upward trend, reaching 19.6% of GDP by 2024.[7][8] Of each dollar spent on health care in the United States, 31% goes to hospital care, 21% goes to physician/clinical services, 10% to pharmaceuticals, 4% to dental, 6% to nursing homes and 3% to home health care, 3% for other retail products, 3% for government public health activities, 7% to administrative costs, 7% to investment, and 6% to other professional services (physical therapists, optometrists, etc.).[9]

The Congressional Budget Office reported in 2008 that "about half of all growth in health care spending in the past several decades was associated with changes in medical care made possible by advances in technology." Other factors included higher income levels, changes in insurance coverage, and rising prices.[14] Hospitals and physician spending take the largest share of the health care dollar, while prescription drugs take about 10%.[15] The use of prescription drugs is increasing among adults who have drug coverage.[16]

In 2009, the average private room in a nursing home cost $219 daily. Assisted living costs averaged $3,131 monthly. Home health aides averaged $21 per hour. Adult day care services averaged $67 daily.[17]

Per capita

The Office of the Actuary (OACT) of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services publishes data on total health care spending in the United States, including both historical levels and future projections.[18] In 2007, the U.S. spent $2.26 trillion on health care, or $7,439 per person, up from $2.1 trillion, or $7,026 per capita, the previous year.[19] Spending in 2006 represented 16% of GDP, an increase of 6.7% over 2004 spending. Growth in spending is projected to average 6.7% annually over the period 2007 through 2017.

In 2009, the United States federal, state and local governments, corporations and individuals, together spent $2.5 trillion, $8,047 per person, on health care.[20] This amount represented 17.3% of the GDP, up from 16.2% in 2008.[20] Health insurance costs are rising faster than wages or inflation,[21] and medical causes were cited by about half of bankruptcy filers in the United States in 2001.[22]

Rate of increase

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reported in 2013 that the rate of increase in annual healthcare costs has fallen since 2002. However, costs relative to GDP and per capita continue to rise. Per capita cost increases have averaged 5.4% since 2000.[23]

Several studies have attempted to explain the reduction in the rate of annual increase. Reasons include, among others:

- Higher unemployment due to the 2008-2012 recession, which has limited the ability of consumers to purchase healthcare;

- Rising out-of-pocket payments;

- Deductibles (the amount a person pays before insurance begins to cover claims) have risen sharply. Workers must pay a larger share of their own health costs, and generally forces them to spend less; and

- The proportion of workers with employer-sponsored health insurance enrolled in a plan that required a deductible climbed to about three-quarters in 2012 from about half in 2006.[24][25]

In September 2008 The Wall Street Journal reported that consumers were reducing their health care spending in response to the current economic slow-down. Both the number of prescriptions filled and the number of office visits dropped between 2007 and 2008. In one survey, 22% of consumers reported going to the doctor less often, and 11% reported buying fewer prescription drugs.[26]

Relative to other countries

One analysis of international spending levels in the year 2000 found that while the U.S. spends more on health care than other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the use of health care services in the U.S. is below the OECD median by most measures. The authors of the study concluded that the prices paid for health care services are much higher in the U.S.[27] Economist Hans Sennholz has argued that the Medicare and Medicaid programs may be the main reason for rising health care costs in the U.S.[28]

Concentration

Health care spending in the United States is concentrated. An analysis of the 2008 and 2009 data by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) found that the 1% of the population with the highest spending accounted for 27% of aggregate health care spending. The highest-spending 5% of the population accounted for more than half of all spending. This reflects spending in 2009, as well.[29][30] In both 2008 and 2009, the top 30 percent of the population ranked by expenditures accounted for nearly 89 percent of health care expenditures.[29] Further, the bottom 50 percent of the population ranked by their expenditures accounted for only 3.1 percent and 2.9 percent of the total for 2008 and 2009.[29] Relative to the overall population, those who remained in the top 10% of spenders between 2008 and 2009 were more likely to be in fair or poor health, elderly, female, non-Hispanic whites and those with public-only coverage. Those who remained in the bottom half of spenders were more likely to be in excellent health, children and young adults, men, Hispanics, and the uninsured. These patterns were stable through the 1970s and 1980s, and some data suggest that they may have been typical of the mid-to-early 20th century as well.[31]

An earlier study by AHRQ the found significant persistence in the level of health care spending from year to year. Of the 1% of the population with the highest health care spending in 2002, 24.3% maintained their ranking in the top 1% in 2003. Of the 5% with the highest spending in 2002, 34% maintained that ranking in 2003. Individuals over age 45 were disproportionately represented among those who were in the top decile of spending for both years.[32]

Seniors spend, on average, far more on health care costs than either working-age adults or children. The pattern of spending by age was stable for most ages from 1987 through 2004, with the exception of spending for seniors age 85 and over. Spending for this group grew less rapidly than that of other groups over this period.[33]

The 2008 edition of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care[34] found that providing Medicare beneficiaries with severe chronic illnesses with more intense health care in the last two years of life—increased spending, more tests, more procedures and longer hospital stays—is not associated with better patient outcomes. There are significant geographic variations in the level of care provided to chronically ill patients, only 4% of which are explained by differences in the number of severely ill people in an area. Most of the differences are explained by differences in the amount of "supply-sensitive" care available in an area. Acute hospital care accounts for over half (55%) of the spending for Medicare beneficiaries in the last two years of life, and differences in the volume of services provided is more significant than differences in price. The researchers found no evidence of "substitution" of care, where increased use of hospital care would reduce outpatient spending (or vice versa).[34][35]

Hospitalization Costs

According to a report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), aggregate U.S. hospital costs in 2011 were $387.3 billion—a 63% increase since 1997 (inflation adjusted). Costs per stay increased 47% since 1997, averaging $10,000 in 2011.[36]

Cost forecasts

The Congressional Budget Office reported in February 2013 that Medicare costs were 3.5% GDP in 2012, down from 3.7% GDP in 2011 but up from 2.2% GDP in 2000. Medicaid costs were 1.6% GDP in 2012, down from 1.8% GDP in 2011 but up from 1.2% GDP in 2000.[4]

CBO projected in June 2012 that federal spending on healthcare programs will rise from 5.4% GDP in 2012 to 9.6% GDP by 2037. This would be driven by a significant increase in the number of program beneficiaries due to the retirement of the Baby Boomers, along with healthcare cost inflation.[5]

The Medicare Trustees provide an annual report of the program's finances. The forecasts from 2009 and 2015 differ materially, mainly due to changes in the projected rate of healthcare cost increases, which have moderated considerably. Rather than rising to nearly 12% GDP over the forecast period (through 2080) as forecast in 2009, the 2015 forecast has Medicare costs rising to 6% GDP, comparable to the Social Security program.[37]

The increase in healthcare costs is one of the primary drivers of long-term budget deficits. The long-term budget situation has considerably improved in the 2015 forecast versus the 2009 forecast per the Trustees Report.[38]

Payment

Doctors and hospitals are generally funded by payments from patients and insurance plans in return for services rendered (fee-for-service or FFS).

Around 84.7% of Americans have some form of health insurance; either through their employer or the employer of their spouse or parent (59.3%), purchased individually (8.9%), or provided by government programs (27.8%; there is some overlap in these figures).[12] All government health care programs have restricted eligibility, and there is no government health insurance company which covers all Americans. Americans without health insurance coverage in 2007 totaled 15.3% of the population, or 45.7 million people.[12]

Among those whose employer pays for health insurance, the employee may be required to contribute part of the cost of this insurance, while the employer usually chooses the insurance company and, for large groups, negotiates with the insurance company.

In 2004, private insurance paid for 36% of personal health expenditures, private out-of-pocket 15%, federal government 34%, state and local governments 11%, and other private funds 4%.[39] Due to "a dishonest and inefficient system" that sometimes inflates bills to ten times the actual cost, even insured patients can be billed more than the real cost of their care.[40]

Insurance for dental and vision care (except for visits to ophthalmologists, which are covered by regular health insurance) is usually sold separately. Prescription drugs are often handled differently from medical services, including by the government programs. Major federal laws regulating the insurance industry include COBRA and HIPAA.

Individuals with private or government insurance are limited to medical facilities which accept the particular type of medical insurance they carry. Visits to facilities outside the insurance program's "network" are usually either not covered or the patient must bear more of the cost. Hospitals negotiate with insurance programs to set reimbursement rates; some rates for government insurance programs are set by law. The sum paid to a doctor for a service rendered to an insured patient is generally less than that paid "out of pocket" by an uninsured patient. In return for this discount, the insurance company includes the doctor as part of their "network", which means more patients are eligible for lowest-cost treatment there. The negotiated rate may not cover the cost of the service, but providers (hospitals and doctors) can refuse to accept a given type of insurance, including Medicare and Medicaid. Low reimbursement rates have generated complaints from providers, and some patients with government insurance have difficulty finding nearby providers for certain types of medical services.

Charity care for those who cannot pay is sometimes available, and is usually funded by non-profit foundations, religious orders, government subsidies, or services donated by the employees. Massachusetts and New Jersey have programs where the state will pay for health care when the patient cannot afford to do so.[41] The City and County of San Francisco is also implementing a citywide health care program for all uninsured residents, limited to those whose incomes and net worth are below an eligibility threshold. Some cities and counties operate or provide subsidies to private facilities open to all regardless of the ability to pay. Means testing is applied, and some patients of limited means may be charged for the services they use.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act requires virtually all hospitals to accept all patients, regardless of the ability to pay, for emergency room care. The act does not provide access to non-emergency room care for patients who cannot afford to pay for health care, nor does it provide the benefit of preventive care and the continuity of a primary care physician. Emergency health care is generally more expensive than an urgent care clinic or a doctor's office visit, especially if a condition has worsened due to putting off needed care. Emergency rooms are typically at, near, or over capacity. Long wait times have become a problem nationally, and in urban areas some ERs are put on "diversion" on a regular basis, meaning that ambulances are directed to bring patients elsewhere.[42]

Private

Most Americans under age 65 (59.3%) receive their health insurance coverage through an employer (which includes both private as well as civilian public-sector employers) under group coverage, although this percentage is declining. Costs for employer-paid health insurance are rising rapidly: since 2001, premiums for family coverage have increased 78%, while wages have risen 19% and inflation has risen 17%, according to a 2007 study by the Kaiser Family Foundation.[21] Workers with employer-sponsored insurance also contribute; in 2007, the average percentage of premium paid by covered workers is 16% for single coverage and 28% for family coverage.[21] In addition to their premium contributions, most covered workers face additional payments when they use health care services, in the form of deductibles and copayments.

Just less than 9% of the population purchases individual health care insurance.[12] Insurance payments are a form of cost-sharing and risk management where each individual or their employer pays predictable monthly premiums. This cost-spreading mechanism often picks up much of the cost of health care, but individuals must often pay up-front a minimum part of the total cost (a deductible), or a small part of the cost of every procedure (a copayment). Private insurance accounts for 35% of total health spending in the United States, by far the largest share among OECD countries. Beside the United States, Canada and France are the two other OECD countries where private insurance represents more than 10% of total health spending.[43]

Provider networks can be used to reduce costs by negotiating favorable fees from providers, selecting cost effective providers, and creating financial incentives for providers to practice more efficiently.[44] A survey issued in 2009 by America's Health Insurance Plans found that patients going to out-of-network providers are sometimes charged extremely high fees.[45][46]

Defying many analysts' expectations, PPOs have gained market share at the expense of HMOs over the past decade.[47]

Just as the more loosely managed PPOs have edged out HMOs, HMOs themselves have also evolved towards less tightly managed models. The first HMOs in the U.S., such as Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, California, and the Health Insurance Plan (HIP) in New York, were "staff-model" HMOs, which owned their own health care facilities and employed the doctors and other health care professionals who staffed them. The name health maintenance organization stems from the idea that the HMO would make it its job to maintain the enrollee's health, rather than merely to treat illnesses. In accordance with this mission, managed care organizations typically cover preventive health care. Within the tightly integrated staff-model HMO, the HMO can develop and disseminate guidelines on cost-effective care, while the enrollee's primary care doctor can act as patient advocate and care coordinator, helping the patient negotiate the complex health care system. Despite a substantial body of research demonstrating that many staff-model HMOs deliver high-quality and cost-effective care, they have steadily lost market share. They have been replaced by more loosely managed networks of providers with whom health plans have negotiated discounted fees. It is common today for a physician or hospital to have contracts with a dozen or more health plans, each with different referral networks, contracts with different diagnostic facilities, and different practice guidelines.

Public

Government programs directly cover 27.8% of the population (83 million),[12] including the elderly, disabled, children, veterans, and some of the poor, and federal law mandates public access to emergency services regardless of ability to pay. Public spending accounts for between 45% and 56.1% of U.S. health care spending.[13] Per-capita spending on health care by the U.S. government placed it among the top ten highest spenders among United Nations member countries in 2004.[48]

However, all government-funded healthcare programs exist only in the form of statutory law, and accordingly can be amended or revoked like any other statute. There is no constitutional right to healthcare. The U.S. Supreme Court explained in 1977 that "the Constitution imposes no obligation on the States to pay ... any of the medical expenses of indigents."[49]

Government funded programs include:

- Medicare, generally covering citizens and long-term residents 65 years and older and the disabled.

- Medicaid, generally covering low income people in certain categories, including children, pregnant women, and the disabled. (Administered by the states.)

- State Children's Health Insurance Program, which provides health insurance for low-income children who do not qualify for Medicaid. (Administered by the states, with matching state funds.)

- Various programs for federal employees, including TRICARE for military personnel (for use in civilian facilities)

- The Veterans Administration, which provides care to veterans, their families, and survivors through medical centers and clinics.[50]

- Title X which funds reproductive health care

- State and local health department clinics

- Indian health service

- National Institutes of Health treats patients who enroll in research for free.

- Medical Corps of various branches of the military.

- Certain county and state hospitals

- Government run community clinics

The exemption of employer-sponsored health benefits from federal income and payroll taxes distorts the health care market.[51] The U.S. government, unlike some other countries, does not treat employer funded health care benefits as a taxable benefit in kind to the employee. The value of the lost tax revenue from a benefits in kind tax is an estimated $150 billion a year.[52] Some regard this as being disadvantageous to people who have to buy insurance in the individual market which must be paid from income received after tax.[53]

Health insurance benefits are an attractive way for employers to increase the salary of employees as they are nontaxable. As a result, 65% of the non-elderly population and over 90% of the privately insured non-elderly population receives health insurance at the workplace.[54] Additionally, most economists agree that this tax shelter increases individual demand for health insurance, leading some to claim that it is largely responsible for the rise in health care spending.[54]

In addition the government allows full tax shelter at the highest marginal rate to investors in health savings accounts (HSAs). Some have argued that this tax incentive adds little value to national health care as a whole because the most wealthy in society tend also to be the most healthy. Also it has been argued, HSAs segregate the insurance pools into those for the wealthy and those for the less wealthy which thereby makes equivalent insurance cheaper for the rich and more expensive for the poor.[55] However, one advantage of health insurance accounts is that funds can only be used towards certain HSA qualified expenses, including medicine, doctor's fees, and Medicare Parts A and B. Funds cannot be used towards expenses such as cosmetic surgery.[56]

There are also various state and local programs for the poor. In 2007, Medicaid provided health care coverage for 39.6 million low-income Americans (although Medicaid covers approximately 40% of America's poor),[57] and Medicare provided health care coverage for 41.4 million elderly and disabled Americans.[12] Enrollment in Medicare is expected to reach 77 million by 2031, when the baby boom generation is fully enrolled.[58]

It has been reported that the number of physicians accepting Medicaid has decreased in recent years due to relatively high administrative costs and low reimbursements.[59] In 1997, the federal government also created the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), a joint federal-state program to insure children in families that earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but cannot afford health insurance.[60] SCHIP covered 6.6 million children in 2006,[61] but the program is already facing funding shortfalls in many states.[62] The government has also mandated access to emergency care regardless of insurance status and ability to pay through the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), passed in 1986,[63] but EMTALA is an unfunded mandate.[64]

The uninsured

Number of uninsured

Some Americans do not qualify for government-provided health insurance, are not provided health insurance by an employer, and are unable to afford, cannot qualify for, or choose not to purchase, private health insurance. When charity or "uncompensated" care is not available, they sometimes simply go without needed medical treatment. This problem has become a source of considerable political controversy on a national level.

According to the US Census Bureau, in 2007, 45.7 million people in the U.S. (15.3% of the population) were without health insurance for at least part of the year. This number was down slightly from the previous year, with nearly 3 million more people receiving government coverage and a slightly lower percentage covered under private plans than the year previous.[12] Other studies have placed the number of uninsured in the years 2007–2008 as high as 86.7 million, about 29% of the US population.[65][66]

Among the uninsured population, the Census Bureau says, nearly 37 million were employment-age adults (ages 18 to 64), and more than 27 million worked at least part-time. About 38% of the uninsured live in households with incomes of $50,000 or more.[12] According to the Census Bureau, nearly 36 million of the uninsured are legal U.S citizens. Another 9.7 million are noncitizens, but the Census Bureau does not distinguish in its estimate between legal noncitizens and illegal immigrants.[12] Nearly one fifth of the uninsured population is able to afford insurance, almost one quarter is eligible for public coverage, and the remaining 56% need financial assistance (8.9% of all Americans).[67] Extending coverage to all who are eligible remains a fiscal challenge.[68]

A 2003 study in Health Affairs estimated that uninsured people in the U.S. received approximately $35 billion in uncompensated care in 2001.[69] The study noted that this amount per capita was half what the average insured person received. The study found that various levels of government finance most uncompensated care, spending about $30.6 billion on payments and programs to serve the uninsured and covering as much as 80–85% of uncompensated care costs through grants and other direct payments, tax appropriations, and Medicare and Medicaid payment add-ons. Most of this money comes from the federal government, followed by state and local tax appropriations for hospitals. Another study by the same authors in the same year estimated the additional annual cost of covering the uninsured (in 2001 dollars) at $34 billion (for public coverage) and $69 billion (for private coverage). These estimates represent an increase in total health care spending of 3–6% and would raise health care's share of GDP by less than one percentage point, the study concluded.[70] Another study published in the same journal in 2004 estimated that the value of health forgone each year because of uninsurance was $65–$130 billion and concluded that this figure constituted "a lower-bound estimate of economic losses resulting from the present level of uninsurance nationally."[71]

The health insurance system in America, in contrast with health insurance in almost all other developed nations, is fundamentally a voluntary one. There are many perspectives on the purpose of health insurance in the United States. For consumers, health insurance serves two main purposes: it provides access to affordable health care through preferential pricing and it offers financial protection from unexpected health care costs. For clinicians and other health care providers, insurance ensures financial stability of the practice/office. Health insurance was first developed by Baylor University Hospital for exactly that purpose.[72]

Effects on uninsured

From 2000 to 2004, the Institute of Medicine's Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance issued a series of six reports that reviewed and reported on the evidence on the effects of the lack of health insurance coverage.[73]

The reports concluded that the committee recommended that the nation should implement a strategy to achieve universal health insurance coverage. As of 2011, a comprehensive national plan to address what universal health plan supporters terms "America's uninsured crisis", has yet to be enacted. A few states have achieved progress towards the goal of universal health insurance coverage, such as Maine, Massachusetts, and Vermont, but other states including California, have failed attempts of reforms.[74]

The six reports created by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) found that the principal consequences of uninsurance were the following: Children and Adults without health insurance did not receive needed medical care; they typically live in poorer health and die earlier than children or adults who have insurance. The financial stability of a whole family can be put at risk if only one person is uninsured and needs treatment for unexpected health care costs. The overall health status of a community can be adversely affected by a higher percentage of uninsured people within the community. The coverage gap between the insured and the uninsured has not decreased even after the recent federal initiatives to extend health insurance coverage.[74]

The last report was published in 2004 and was named Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations. This report recommended the following: The President and Congress need to develop a strategy to achieve universal insurance coverage and establish a firm schedule to reach this goal by the year 2010. The committee also recommended that the federal and state governments provide sufficient resources for Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) to cover all persons currently eligible until the universal coverage takes effect. They also warned that the federal and state governments should prevent the erosion of outreach efforts, eligibility, enrollment, and coverage of these specific programs.[74]

Some people think that not having health insurance will have adverse consequences for the health of the uninsured.[75] On the other hand, some people believe that children and adults without health insurance have access to needed health care services at hospital emergency rooms, community health centers, or other safety net facilities offering charity care.[76] Some observers note that there is a solid body of evidence showing that a substantial proportion of U.S. health care expenditures is directed toward care that is not effective and may sometimes even be harmful.[77] At least for the insured population, spending more and using more health care services does not always yield better health outcomes or increase life expectancy.[78]

Children in America are typically perceived as in good health relative to adults, due to the fact that most serious health problems occur later in one's life. Certain conditions including asthma, diabetes, and obesity have become much more prevalent among children in the past few decades.[74] There is also a growing population of vulnerable children with special health care needs that require ongoing medical attention, which would not be accessible without health insurance. More than 10 million children in the United States meet the federal definition of children with special health care needs "who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, development, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally".[79] These children require health related services of an amount beyond that required by the average children in America. Typically when children acquire health insurance, they are much less likely to experience previously unmet health care needs, this includes the average child in America and children with special health care needs.[74] The Committee on Health Insurance Status and Its Consequences concluded that the effects of health insurance on children's health outcomes: Children with health insurance receive more timely diagnosis of serious health conditions, experience fewer hospitalizations, and miss fewer days of school.

The same committee analyzed the effects of health insurance on adult's health outcomes: adults who do not have health insurance coverage who acquire Medicare coverage at age 65, experience substantially improved health and functional status, particularly those who have cardiovascular disease or diabetes. Adults who have cardiovascular disease or other cardiac risk factors that are uninsured are less likely to be aware of their condition, which leads to worse health outcomes for those individuals. Without health insurance, adults are more likely to be diagnosed with certain cancers that would have been detectable earlier by screening by a clinician if they had regularly visited a doctor. As a consequence, these adults are more likely to die from their diagnosed cancer or suffer poorer health outcomes.[74]

Many towns and cities in the United States have high concentrations of people under the age of 65 who lack health insurance.[80] There are implications of high rates of uninsurance for communities and for insured people in those communities. Institute of Medicine committee warned of the potential problems of high rates of uninsurance for local health care, including reduced access to clinic-based primary care, specialty services, and hospital-based emergency services.[81]

Expenditures by the uninsured

Estimates for 2008 reported that the uninsured would spend $30 billion for healthcare and receive $56 billion in uncompensated care, and that if everyone were covered by insurance then overall costs would increase by $123 billion.[82] A 2003 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report estimated total cost of health care provided to the uninsured at $98.9 billion in 2001, including $26.4 billion in out-of-pocket spending by the uninsured, with $34.5 billion in "free" "uncompensated" care covered by government subsidies of $30.6 billion to hospitals and clinics and $5.1 billion in donated services by physicians.[83]

Role of government in health care market

Numerous publicly funded health care programs help to provide for the elderly, disabled, military service families and veterans, children, and the poor,[84] and federal law ensures public access to emergency services regardless of ability to pay;[85] however, a system of universal health care has not been implemented nationwide. However, as the OECD has pointed out, the total U.S. public expenditure for this limited population would, in most other OECD countries, be enough for the government to provide primary health insurance for the entire population.[43] Although the federal Medicare program and the federal-state Medicaid programs possess some monopsonistic purchasing power, the highly fragmented buy side of the U.S. health system is relatively weak by international standards, and in some areas, some suppliers such as large hospital groups have a virtual monopoly on the supply side.[86] In most OECD countries, there is a high degree of public ownership and public finance.[87] The resulting economy of scale in providing health care services appears to enable a much tighter grip on costs.[87] The U.S., as a matter of oft-stated public policy, largely does not regulate prices of services from private providers, assuming the private sector to do it better.[88]

Massachusetts has adopted a universal health care system through the Massachusetts 2006 Health Reform Statute. It mandates that all residents who can afford to do so purchase health insurance, provides subsidized insurance plans so that nearly everyone can afford health insurance, and provides a "Health Safety Net Fund" to pay for necessary treatment for those who cannot find affordable health insurance or are not eligible.[89]

In July 2009, Connecticut passed into law a plan called SustiNet, with the goal of achieving health-care coverage of 98% of its residents by 2014.[90]

Impact on U.S. economic productivity

On March 1, 2010, billionaire investor Warren Buffett said that the high costs paid by U.S. companies for their employees' health care put them at a competitive disadvantage. He compared the roughly 17% of GDP spent by the U.S. on health care with the 9% of GDP spent by much of the rest of the world, noted that the U.S. has fewer doctors and nurses per person, and said, "[t]hat kind of a cost, compared with the rest of the world, is like a tapeworm eating at our economic body."[91]

Proposed solutions

Increased spending on disease prevention is often suggested as a way of reducing health care spending.[92] Whether prevention saves or costs money depends on the intervention. Childhood vaccinations,[92] or contraceptives[93] save much more than they cost. Research suggests that in many cases prevention does not produce significant long-term cost savings.[92] Some interventions may be cost-effective by providing health benefits, while others are not cost-effective.[92] Preventive care is typically provided to many people who would never become ill, and for those who would have become ill is partially offset by the health care costs during additional years of life.[92] On the other hand, research conducted by Novartis argues that the countries that have excelled in getting the highest value for healthcare spending are the ones who have invested more in prevention, early diagnosis and treatment. The trick is to avoid getting patients to hospital, which is where highest healthcare dollars are being consumed. Not all preventive measures have good ROI (EG. Global vaccination campaign for a rare infectious diseases). However, preventive measures such as diet, exercises and reduction of tobacco intake would have broad impact on many diseases and will offer good return of investment.[94]

Eliminating waste is another solution. In December 2011, the outgoing Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Dr. Donald Berwick, asserted that 20% to 30% of health care spending is waste. He listed five causes for the waste: (1) overtreatment of patients, (2) the failure to coordinate care, (3) the administrative complexity of the health care system, (4) burdensome rules and (5) fraud.[95]

Further reading

- Goodman, John C. Priceless : curing our healthcare crisis. Oakland, Calif.: Independent Institute. ISBN 978-1-59813-083-6.

- Flower, Joe. Healthcare beyond reform : doing it right for half the cost. Boca Raton, FL.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-4665-1121-7.

- Reid, T.R. (2010). The healing of America : a global quest for better, cheaper, and fairer health care. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-0-14-311821-3.

- Makary, Marty. Unaccountable : what hospitals won't tell you and how transparency can revolutionize health care (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-60819-836-8.

- Herzlinger, Regina (2007). Who killed health care? : America's $2 trillion medical problem--and the consumer-driven cure. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-148780-1.

References

- ↑ OECD Statistical Database-Healthcare Spending Per Capital PPP or USD Basis-Retrieved January 2016

- ↑ OECD-Briefing Note-OECD Health Statistics 2014 How does the United States compare?-Retrieved January 11, 2016

- 1 2 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services-Statistics, Trends and Reports Retrieved September 23, 2015

- 1 2 CBO-Budget And Economic Outlook: 2015 To 2025-January 2015

- 1 2 CBO-Long Term Budget Outlook 2015-June 2015

- 1 2 WHO (2015). World health statistics 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 069443 9.

- 1 2 "National Health Expenditure Data: NHE Fact Sheet," Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, referenced September 23, 2015

- 1 2 Sean Keehan, Andrea Sisko, Christopher Truffer, Sheila Smith, Cathy Cowan, John Poisal, M. Kent Clemens, and the National Health Expenditure Accounts Projections Team, "Health Spending Projections Through 2017: The Baby-Boom Generation Is Coming To Medicare", Health Affairs Web Exclusive, February 26, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- 1 2 U.S. Healthcare Costs: Background Brief. KaiserEDU.org. See also Trends in Health Care Costs and Spending, March 2009 - Fact Sheet. Kaiser Permanente.

- ↑ Roehr, Bob (2008). "Health care in US ranks lowest among developed countries". BMJ 337 (jul21 1): a889. doi:10.1136/bmj.a889. PMID 18644774.

- ↑ Davis, Karen, Schoen, Cathy, and Stremikis, Kristof (June 2010). "Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, 2010 Update". The Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2007." U.S. Census Bureau. Issued August 2008.

- 1 2 Thomas M. Selden and Merrile Sing, "The Distribution Of Public Spending For Health Care In The United States, 2002," Health Affairs 27, no. 5 (2008): w349-w359 (published online 29 July 2008)

- ↑ U.S. Congressional Budget Office, "Technological Change and the Growth of Health Care Spending," January 2008

- ↑ California HealthCare Foundation. http://www.chcf.org/documents/insurance/HealthCareCosts07.pdf "Health Care Costs 101" 2007 Edition. Katherine B. Wilson. April 2007.

- ↑ Emily Cox, Doug Mager, Ed Weisbart, "Geographic Variation Trends in Prescription Use: 2000 to 2006", Express Scripts, January 2008

- ↑ "Long term care costs rise across the board from 2008 to 2009" (PDF). metlife.com. 27 October 2009.

- ↑ "National Health Expenditure Data: Overview," Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ↑ "National Health Expenditures, Forecast summary and selected tables", Office of the Actuary in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- 1 2 Jones, Brent (2010-02-04). "Medical expenses have 'very steep rate of growth'". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- 1 2 3 "Health Insurance Premiums Rise 6.1 Percent In 2007, Less Rapidly Than In Recent Years But Still Faster Than Wages And Inflation" (Press release). Kaiser Family Foundation. 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ↑ "Illness And Injury As Contributors To Bankruptcy", by David U. Himmelstein, Elizabeth Warren, Deborah Thorne, and Steffie Woolhandler, published at Health Affairs journal in 2005, Accessed 10 May 2006.

- ↑ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services-Statistics, Trends and Reports-Retrieved June 9, 2013

- ↑ Annie Lowrey (May 2013). "Slowdown in Rise of Healthcare Costs May Persist". The New York Times. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ↑ Yuval Levin (May 2013). "Healthcare Costs and Budget". National Review Online. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ↑ Vanessa Fuhrmans, "Consumers Cut Health Spending, As Economic Downturn Takes Toll," The Wall Street Journal, September 22, 2008

- ↑ Gerard F. Anderson, Uwe E. Reinhardt, Peter S. Hussey and Varduhi Petrosyan, "It's The Prices, Stupid: Why The United States Is So Different From Other Countries", Health Affairs, Volume 22, Number 3, May/June 2003. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ↑ Sennholz, Hans. Why is Medical Care so Expensive?. August 22, 2006.

- 1 2 3 AHRQ Report

- ↑ "5% of patients account for half of health care spending". USA Today. January 11, 2012.

- ↑ Marc L. Berk and Alan C. Monheit, "The Concentration Of Health Care Expenditures, Revisited", Health Affairs, Volume 20, Number 2, March/April 2001. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- ↑ Steven B. Cohen and William Yu, "The Persistence in the Level of Health Expenditures over Time: Estimates for the U.S. Population, 2002–2003," MEPS Statistical Brief #124, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, May 2006

- ↑ Micah Hartman, Aaron Catlin, David Lassman, Jonathan Cylus and Stephen Heffler, "U.S. Health Spending By Age, Selected Years Through 2004", Health Affairs web exclusive, November 6, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- 1 2 John E. Wennberg, Elliott S. Fisher, David C. Goodman, and Jonathan S. Skinner, "Tracking the Care of Patients with Severe Chronic Illness: the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care 2008." The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, May 2008, ISBN 978-0-9815862-0-5 (Executive Summary)

- ↑ "Coverage & Access | More Aggressive Hospital Care Does Not Lead to Improved Patient Outcomes in All Cases, Study Finds," Kaiser Daily Health Policy Report, Kaiser Family Foundation, May 30, 2008

- ↑ Pfuntner A., Wier L.M., Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #166. November 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. .

- ↑ 2015 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medicare Insurance Trust Funds-Retrieved July 28, 2015

- ↑ NYT-Paul Krugman-The Disappearing Entitlements Crisis-July 26, 2015

- ↑ Health, United States, 2007. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- ↑ Lopez, Steve (November 22, 2009). "The emergency room bill is enough to make you sick". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ See Massachusetts health care reform for Massachusetts and charity care for New Jersey.

- ↑ See emergency department for details.

- 1 2 "OECD Health Data 2009" (pdf). How Does the United States Compare. OECD. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ Managed Care: Integrating the Delivery and Financing of Health Care - Part A, Health Insurance Association of America, 1995, p. 9 ISBN 978-1-879143-26-5

- ↑ THE VALUE OF PROVIDER NETWORKS AND THE ROLE OF OUT-OF-NETWORK CHARGES IN RISING HEALTH CARE COSTS: A SURVEY OF CHARGES BILLED BY OUT-OF-NETWORK PHYSICIANS, America's Health Insurance Plans, August 2009

- ↑ Gina Kolata, "Survey Finds High Fees Common in Medical Care", The New York Times, August 11, 2009

- ↑ Hurley RE, Strunk BC, White JS (2004). "The puzzling popularity of the PPO". Health Aff (Millwood) 23 (2): 56–68. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.56. PMID 15046131.

- ↑ Core Health Indicators: Per capita government expenditure on health at average exchange rate World Health Organization. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Maher v. Roe, 432 U.S. 464 (1977).

- ↑ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Medicare

- ↑ How the Tax Code Distorts Health Care Cato Institute

- ↑ "The Health Care Crisis and What to Do About It" By Paul Krugman, Robin Wells, New York Review of Books, March 23, 2006

- ↑ http://www.setaxequity.org/ Equity for Our Nation's Self-Employed

- 1 2 Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance: Past, Present and Future Journal of Forensic Economics

- ↑ LATEST ENROLLMENT DATA STILL FAIL TO DISPEL CONCERNS ABOUT HEALTH SAVINGS ACCOUNTS: The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

- ↑ "Health Savings Accounts FAQ". Health 401k. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ Unsettling Scores: A Ranking of State Medicaid Programs, P. 15

- ↑ "Health and Human Services Statistics 2006" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ↑ Cunningham P, May J (August 2006). "Medicaid patients increasingly concentrated among physicians". Track Rep (16): 1–5. PMID 16918046.

- ↑ "SCHIP Overview". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ↑ "SCHIP Ever Enrolled in Year" (PDF). U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ↑ "President's FY 2008 Budget and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)" (PDF). Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ↑ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act

- ↑ Rowes, Jeffrey (2000). "EMTALA: OIG/HCFA Special Advisory Bulletin Clarifies EMTALA, American College of Emergency Physicians Criticizes It". Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 28 (1): 9092. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720x.2000.tb00324.x. Archived from the original on 2008-01-29. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ↑ Families USA (2009) press release summarizing a Lewin Group (wholly owned by United Healthcare insurance company) study: "New Report Finds 86.7 Million Americans Were Uninsured at Some Point in 2007-2008"

- ↑ http://www.familiesusa.org/assets/pdfs/americans-at-risk.pdf

- ↑ Dubay L, Holahan J and Cook A.,The Uninsured and the Affordability of Health Insurance Coverage, Health Affairs (Web Exclusive), November 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Characteristics of the Uninsured: Who is Eligible for Public Coverage and Who Needs Help Affording Coverage?" (PDF). Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ↑ Jack Hadley and John Holahan,How Much Medical Care Do the Uninsured Use and Who Pays for It?, Health Affairs Web Exclusive, 2003-02-13. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Jack Hadley and John Holahan, Covering The Uninsured: How Much Would It Cost?, Health Affairs Web Exclusive, 2003-06-04. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Wilhelmine Miller, Elizabeth Richardson Vigdor, and Willard G. Manning, Covering The Uninsured: What Is It Worth?, Health Affairs Web Exclusive, 2004-03-31. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Porter, M.E., and E.O. Teisberg. 2006. Redefining health care: Creating value-based competition on results. Cambridge, Ma: Harvard Business Press.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine. Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance (January 13, 2004). Insuring America's health: principles and recommendations. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-309-52826-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Committee on Health Insurance Status and Its Consequences (Author). America's Uninsured Crisis : Consequences for Health and Health Care. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press, 2009

- ↑ Fisher E. S., Wennberg D. E., Stukel T. A., Gottlieb D. J., Lucas F. L., Pinder E. L. (2003). "The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: The content, quality, and accessibility of care". Annals of Internal Medicine 138 (4): 273–287. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. PMID 12585825.

- ↑ Fuchs, V. R. 2004. Perspective: More variation in use of case, more flat-of-the-curve medicine. Health Affairs 104.

- ↑ Wennberg, D. E., and J. E. Wennberg. 2003. Perspective: Addressing variations: Is there hope for the future? Health Affairs w3.614-w3.617

- ↑ Wennberg, J. E., and E. S. Fisher, and S. M. Sharp. 2006. The care of patients with severe chronic illness. Lebanon, NH: The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care.

- ↑ American Academy of Pediatrics. 2008. Definition of children with special health care needs (CSHCN), http://www.medicalhomeinfo.org/about/def_cshcn.html (accessed December 4, 2011).

- ↑ DeNavas-Walt, C., B. D. Proctor, and J. Smith. 2008. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2007. Washington, DC. U.S Census Bureau.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine. Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance (March 3, 2003). A shared destiny: community effects of uninsurance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-08726-1.

- ↑ http://www.kff.org/uninsured/kcmu082508pkg.cfm

- ↑ Institute of Medicine. Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance (June 17, 2003). Hidden costs, value lost: uninsurance in America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. pp. 47–55. ISBN 978-0-309-08931-9.

- ↑ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Programs & Information.. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ↑ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act.. Retrieved August 30, 2006.

- ↑ Anderson, Gerard F.; Uwe E. Reinhardt; Peter S. Hussey; Varduhi Petrosyan (2009). "It's the prices Stupid: Why the United States is so different from other countries" (pdf). Health Affairs Volume 22, Number 3. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- 1 2 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. "OECD Health Data 2008: How Does Canada Compare?" (PDF). Archived from the original (pdf) on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ Wangsness, Lisa (June 21, 2009). "Health debate shifting to public vs. private". The Boston Globe. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ↑ Fahrenthold DA. "Mass. Bill Requires Health Coverage."

- ↑ http://www.aarp.org/states/ct/advocacy/articles/in_historic_vote_legislature_overrides_sustinet_veto.html

- ↑ Funk, Josh (March 1, 2010). "Buffett says economy recovering but at slow rate". San Francisco Chronicle (SFGate.com). Retrieved Apr 3, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 David Brown, "In the Balance: Some Candidates Disagree, but Studies Show It's Often Cheaper To Let People Get Sick," The Washington Post, April 8, 2008

- ↑ Tsui AO, McDonald-Mosley R, Burke AE (April 2010). "Family planning and the burden of unintended pregnancies". Epidemiol Rev 32 (1): 152–74. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxq012. PMC 3115338. PMID 20570955.

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K7mnJBWb-rE

- ↑ Pear, Robert (Dec 3, 2011). "Health Official Takes Parting Shot at 'Waste'". New York Times. Retrieved Dec 20, 2011.