Ulysses (novel)

1922 first edition cover | |

| Author | James Joyce |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Modernist Novel |

| Publisher | Sylvia Beach |

Publication date | 2 February 1922 |

| Media type | Print book |

Ulysses is a modernist novel by Irish writer James Joyce. It was first serialised in parts in the American journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920, and then published in its entirety by Sylvia Beach in February 1922, in Paris. It is considered to be one of the most important works of modernist literature,[1] and has been called "a demonstration and summation of the entire movement".[2] According to Declan Kiberd, "Before Joyce, no writer of fiction had so foregrounded the process of thinking."[3]

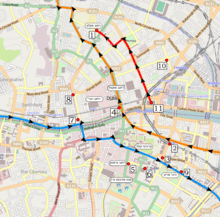

Ulysses chronicles the peripatetic appointments and encounters of Leopold Bloom in Dublin in the course of an ordinary day, 16 June 1904.[4] Ulysses is the Latinised name of Odysseus, the hero of Homer's epic poem Odyssey, and the novel establishes a series of parallels between the poem and the novel, with structural correspondences between the characters and experiences of Leopold Bloom and Odysseus, Molly Bloom and Penelope, and Stephen Dedalus and Telemachus, in addition to events and themes of the early twentieth century context of modernism, Dublin, and Ireland's relationship to Britain. The novel imitates registers of centuries of English literature and is highly allusive.

Ulysses is approximately 265,000 words in length, uses a lexicon of 30,030 words (including proper names, plurals and various verb tenses),[5] and is divided into eighteen episodes. Since publication, the book has attracted controversy and scrutiny, ranging from early obscenity trials to protracted textual "Joyce Wars". Ulysses' stream-of-consciousness technique, careful structuring, and experimental prose — full of puns, parodies, and allusions — as well as its rich characterisation and broad humour, made the book a highly regarded novel in the modernist pantheon. Joyce fans worldwide now celebrate 16 June as Bloomsday. In 1998, the American publishing firm Modern Library ranked Ulysses first on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[6]

Background

Joyce first encountered the figure of Odysseus/Ulysses in Charles Lamb's Adventures of Ulysses—an adaptation of the Odyssey for children, which seemed to establish the Roman name in Joyce's mind. At school he wrote an essay on the character, entitled "My Favourite Hero".[7][8] Joyce told Frank Budgen that he considered Ulysses the only all-round character in literature.[9] He thought about calling his short-story collection Dubliners by the name Ulysses in Dublin,[10] but the idea grew from a story in Dubliners in 1906, to a "short book" in 1907,[11] to the vast novel that he began in 1914.

Structure

Joyce divided Ulysses into 18 chapters or "episodes". At first glance much of the book may appear unstructured and chaotic; Joyce once said that he had "put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant", which would earn the novel "immortality".[12] The two schemata which Stuart Gilbert and Herbert Gorman released after publication to defend Joyce from the obscenity accusations made the links to the Odyssey clear, and also explained the work's internal structure.

Every episode of Ulysses has a theme, technique, and correspondence between its characters and those of the Odyssey. The original text did not include these episode titles and the correspondences; instead, they originate from the Linati and Gilbert schemata. Joyce referred to the episodes by their Homeric titles in his letters. He took the idiosyncratic rendering of some of the titles, e.g. "Nausikaa" and the "Telemachia". from Victor Bérard's two-volume Les Phéniciens et l'Odyssée which he consulted in 1918 in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Part I: The Telemachid

Episode 1, Telemachus

It is 8 a.m. Buck Mulligan, a boisterous medical student, calls Stephen Dedalus (a young writer encountered as the principal subject of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man) up to the roof of the Sandycove Martello tower where they both live. There is tension between Stephen and Mulligan, stemming from a cruel remark Stephen has overheard Mulligan making about his recently deceased mother, May Dedalus, and from the fact that Mulligan has invited an English student, Haines, to stay with them. The three men eat breakfast and walk to the shore, where Mulligan demands from Stephen the key to the tower and a loan. Departing, Stephen declares that he will not return to the tower tonight, as Mulligan, the "usurper", has taken it over.

Episode 2, Nestor

Stephen is teaching a history class on the victories of Pyrrhus of Epirus. After class, one student, Cyril Sargent, stays behind so that Stephen can show him how to do a set of arithmetic exercises. Stephen looks at the aesthetically unappealing Sargent and tries to imagine Sargent's mother's love for him. Stephen then visits school headmaster, Garrett Deasy, from whom he collects his pay and a letter to take to a newspaper office for printing. The two discuss Irish history and the role of Jews in the economy. As Stephen leaves, Deasy makes a final derogatory remark against the Jews, stating that Ireland has never extensively persecuted the Jews because they were never let in to the country. This episode is the source of some of the novel's most famous lines, such as Dedalus's claim that "history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake" and that God is "a shout in the street."

Episode 3, Proteus

Stephen finds his way to Sandymount Strand and mopes around for some time, mulling various philosophical concepts, his family, his life as a student in Paris, and his mother's death. As Stephen reminisces and ponders, he lies down among some rocks, watches a couple and a dog, scribbles some ideas for poetry, picks his nose and urinates behind a rock. This chapter is characterised by a stream of consciousness narrative style that changes focus wildly. Stephen's education is reflected in the many obscure references and foreign phrases employed in this episode, which have earned it a reputation for being one of the book's most difficult chapters.

Part II: The Odyssey

Episode 4, Calypso

The narrative shifts abruptly. The time is again 8 am, but the action has moved across the city and to the second protagonist of the book, Leopold Bloom, a part-Jewish advertising canvasser. Bloom, after starting to prepare breakfast, decides to walk to a butcher to buy a pork kidney. Returning home, he prepares breakfast and brings it with the mail to his wife Molly as she lounges in bed. One of the letters is from her concert manager Blazes Boylan. Bloom is aware that Molly will welcome Boylan into her bed later that day, and is tormented by the thought. Bloom reads a letter from their daughter Milly Bloom. The chapter closes with Bloom defecating in the outhouse.

Episode 5, Lotus Eaters

Bloom makes his way to Westland Row post office where he receives a love letter from one 'Martha Clifford' addressed to his pseudonym, 'Henry Flower'. He meets an acquaintance, and while they chat, Bloom attempts to ogle a woman wearing stockings, but is prevented by a passing tram. Next, he reads the letter and tears up the envelope in an alley. He wanders into a Catholic church service and muses on theology. The priest has the letters I.N.R.I. or I.H.S. on his back; Molly had told Bloom that they meant I have sinned or I have suffered, and Iron nails ran in.[13] He goes to a chemist where he buys a bar of lemon soap. He then meets another acquaintance, Bantam Lyons, who mistakenly takes him to be offering a racing tip for the horse Throwaway. Finally, Bloom heads towards the baths.

Episode 6, Hades

The episode begins with Bloom entering a funeral carriage with three others, including Stephen's father. They drive to Paddy Dignam's funeral, making small talk on the way. The carriage passes both Stephen and Blazes Boylan. There is discussion of various forms of death and burial, and Bloom is preoccupied by thoughts of his dead son, Rudy, and the suicide of his own father. They enter the chapel into the service and subsequently leave with the coffin cart. Bloom sees a mysterious man wearing a mackintosh during the burial. Bloom continues to reflect upon death, but at the end of the episode rejects morbid thoughts to embrace 'warm fullblooded life'.

Episode 7, Aeolus

At the office of the Freeman's Journal, Bloom attempts to place an ad. Although initially encouraged by the editor, he is unsuccessful. Stephen arrives bringing Deasy's letter about 'foot and mouth' disease, but Stephen and Bloom do not meet. Stephen leads the editor and others to a pub, relating an anecdote on the way about 'two Dublin vestals'. The episode is broken into short segments by newspaper-style headlines, and is characterised by an abundance of rhetorical figures and devices.

Episode 8, Lestrygonians

Bloom's thoughts are peppered with references to food as lunchtime approaches. He meets an old flame and hears news of Mina Purefoy's labour. He enters the restaurant of the Burton Hotel where he is revolted by the sight of men eating like animals. He goes instead to Davy Byrne's pub, where he consumes a gorgonzola cheese sandwich and a glass of burgundy, and muses upon the early days of his relationship with Molly and how the marriage has declined: 'Me. And me now.' Bloom's thoughts touch on what goddesses and gods eat and drink. He ponders whether the statues of Greek goddesses in the National Museum have alimentary-canal exits as do mortals. On leaving the pub Bloom heads toward the museum, but spots Boylan across the street and, panicking, rushes into the gallery across the street from the museum.

Episode 9, Scylla and Charybdis

At the National Library, Stephen explains to various scholars his biographical theory of the works of Shakespeare, especially Hamlet, which he claims are based largely on the posited adultery of Shakespeare's wife. Bloom enters the National Library to look up an old copy of the ad he has been trying to place. He encounters Stephen briefly and unknowingly at the end of the episode.

Episode 10, Wandering Rocks

In this episode, nineteen short vignettes depict the wanderings of various characters, major and minor, through the streets of Dublin. The episode ends with an account of the cavalcade of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, William Ward, Earl of Dudley, through the streets, which is encountered by various characters from the novel.

Episode 11, Sirens

In this episode, dominated by motifs of music, Bloom has dinner with Stephen's uncle at a hotel, while Molly's lover, Blazes Boylan, proceeds to his rendezvous with her. While dining, Bloom watches the seductive barmaids and listens to the singing of Stephen's father and others.

Episode 12, Cyclops

This chapter is narrated by an unnamed denizen of Dublin. The narrator goes to Barney Kiernan's pub where he meets a character referred to only as "The Citizen". When Leopold Bloom enters the pub, he is berated by the Citizen, who is a fierce Fenian and anti-Semite. The episode ends with Bloom reminding the Citizen that his Saviour was a Jew. As Bloom leaves the pub, the Citizen, in anger, throws a biscuit tin at Bloom's head, but misses. The chapter is marked by extended tangents made in voices other than that of the unnamed narrator: these include streams of legal jargon, Biblical passages, and elements of Irish mythology.

Episode 13, Nausicaa

Gerty MacDowell, a young woman on Sandymount strand, contemplates love, marriage and femininity as night falls. The reader is gradually made aware that Bloom is watching her from a distance, and as she exposes her legs and underwear to him it is unclear how much of the narrative is actually Bloom’s sexual fantasy. Bloom’s masturbatory climax is echoed by the fireworks at the nearby bazaar. As Gerty leaves, Bloom realises that she has a lame leg. After several digressions of thought he decides to visit Mina Purefoy at the hospital. The style of the first half of the episode borrows from (and parodies) romance magazines and novelettes.

Episode 14, Oxen of the Sun

Bloom visits the maternity hospital where Mina Purefoy is giving birth, and finally meets Stephen, who has been drinking with his medical student friends and is awaiting the promised arrival of Buck Mulligan. They continue on to a pub to continue drinking, following the successful birth of the baby. This chapter is remarkable for Joyce's wordplay, which, among other things, recapitulates the entire history of the English language. After a short incantation, the episode starts with latinate prose, Anglo-Saxon alliteration, and moves on through parodies of, among others, Malory, the King James Bible, Bunyan, Defoe, Sterne, Walpole, Gibbon, Dickens, and Carlyle, before concluding in a haze of nearly incomprehensible slang.

Episode 15, Circe

Episode 15 is written as a play script, complete with stage directions. The plot is frequently interrupted by "hallucinations" experienced by Stephen and Bloom—fantastic manifestations of the fears and passions of the two characters. Stephen and Lynch walk into Nighttown, Dublin's red-light district. Bloom pursues them and eventually finds them at Bella Cohen's brothel, where in the company of her workers including Zoe Higgins, Florry Talbot and Kitty Ricketts he has a series of hallucinations regarding his sexual fetishes, fantasies, and transgressions. Bloom is put in the dock to answer charges by a variety of sadistic, accusing women including Mrs Yelverton Barry, Mrs Bellingham and The Hon Mrs Mervyn Talboys. When Bloom witnesses Stephen overpaying for services received, Bloom decides to hold onto the rest of Stephen's money for safekeeping. Stephen hallucinates that the rotting cadaver of his mother has risen up from the floor to confront him. Terrified, Stephen uses his walking stick to smash a chandelier and then runs out. Bloom quickly pays Bella for the damage, then runs after Stephen. Bloom finds Stephen engaged in a heated argument with an English soldier, Private Carr, who, after a perceived insult to the King, punches Stephen. The police arrive and the crowd disperses. As Bloom is tending to Stephen, Bloom has a hallucination of Rudy, his deceased child.

Part III: The Nostos

Episode 16, Eumaeus

Bloom and Stephen go to the cabman's shelter to restore the latter to his senses. At the cabman's shelter, they encounter a drunken sailor named D. B. Murphy (W. B. Murphy in the 1922 text). The episode is dominated by the motif of confusion and mistaken identity, with Bloom, Stephen and Murphy's identities being repeatedly called into question. The rambling and laboured style of the narrative in this episode reflects the nervous exhaustion and confusion of the two protagonists.

Episode 17, Ithaca

Bloom returns home with Stephen, makes him a cup of cocoa, discusses cultural and lingual differences between them, considers the possibility of publishing Stephen's parable stories, and offers him a place to stay for the night. Stephen refuses Bloom's offer and is ambiguous about Bloom's proposal of future meetings. The two men urinate in the backyard, Stephen departs and wanders off into the night,[14] and Bloom goes to bed, where Molly is sleeping. She awakens and questions him about his day. The episode is written in the form of a rigidly organised and "mathematical" catechism of 309 questions and answers, and was reportedly Joyce's favourite episode in the novel. The deep descriptions range from questions of astronomy to the trajectory of urination and include a famous list of 25 men perceived as Molly's lovers (apparently corresponding to the suitors slain at Ithaca by Odysseus and Telemachus in The Odyssey), including Boylan, and Bloom's psychological reaction to their assignation. While describing events apparently chosen randomly in ostensibly precise mathematical or scientific terms, the episode is rife with errors made by the undefined narrator, many or most of which are volitional by Joyce.[15]

Episode 18, Penelope

The final episode consists of Molly Bloom's thoughts as she lies in bed next to her husband. The episode uses a stream-of-consciousness technique in eight sentences and lacks punctuation. Molly thinks about Boylan and Bloom, her past admirers, including Lieutenant Stanley G. Gardner, the events of the day, her childhood in Gibraltar, and her curtailed singing career. These thoughts are occasionally interrupted by distractions, such as a train whistle or the need to urinate. The episode famously concludes with Molly's remembrance of Bloom's marriage proposal, and of her acceptance: "he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said yes I will Yes."

Editions

Publication history

The publication history of Ulysses is disputed and obscure. There have been at least 18 editions, and variations in different impressions of each edition. Joyce's handwritten manuscripts were typed by a number of amateur typists (one of whom was Robert McAlmon).[16]

According to Joyce scholar Jack Dalton, the first edition of Ulysses contained over two thousand errors but was still the most accurate edition published.[17] As each subsequent edition attempted to correct these mistakes, it incorporated more of its own, a task made more difficult by deliberate errors (See "Episode 17, Ithaca" above) devised by Joyce to challenge the reader.[15]

Notable editions include:

- the first edition published in Paris on 2 February 1922 by Sylvia Beach at Shakespeare and Company (only 1000 copies printed) and printed by Darantiere in Dijon

- the pirated Roth edition, published in New York in 1929

- the Odyssey Press edition of 1932 (including some revisions generally attributed to Stuart Gilbert, and therefore sometimes considered the most accurate edition)

- the 1934 Random House US edition

- the first British edition, of Bodley Head in 1936

- the revised Bodley Head edition of 1960

- the revised Modern Library edition of 1961 (reset from the Bodley Head 1960 edition)

- the Gabler critical and synoptic edition of 1984.

Gabler's "corrected edition"

Hans Walter Gabler's 1984 edition was the most sustained attempt to produce a corrected text, but it received much criticism, most notably from John Kidd. Kidd's main theoretical criticism is of Gabler's choice of a patchwork of manuscripts as his copy-text (the base edition with which the editor compares each variant), but this fault stems from an assumption of the Anglo-American tradition of scholarly editing rather than the blend of French and German editorial theories that actually lay behind Gabler's reasoning.[18] The choice of a multiple copy-text is seen to be problematic in the eyes of some American editors, who generally favour the first edition of any particular work as copy-text.[18] Less subject to differing national editorial theories, however, is the claim that for hundreds of pages—about half the episodes of Ulysses—the extant manuscript is purported to be a "fair copy" which Joyce made for sale to a potential patron. (As it turned out, John Quinn, the Irish-American lawyer and collector, purchased the manuscript.) Diluting this charge somewhat is the fact that the theory of (now lost) final working drafts is Gabler's own. For the suspect episodes, the existing typescript is the last witness. Gabler attempted to reconstruct what he called "the continuous manuscript text", which had never physically existed, by adding together all of Joyce's accretions from the various sources. This allowed Gabler to produce a "synoptic text" indicating the stage at which each addition was inserted. Kidd and even some of Gabler's own advisers believe this method meant losing Joyce's final changes in about two thousand places.[18] Far from being "continuous", the manuscripts seem to be opposite. Jerome McGann describes in detail the editorial principles of Gabler in his article for the journal Criticism, issue 27, 1985. In the wake of the controversy, still other commentators charged that Gabler's changes were motivated by a desire to secure a fresh copyright and another seventy-five years of royalties beyond a looming expiration date.

In June 1988 John Kidd published "The Scandal of Ulysses" in the New York Review of Books,[18] charging that not only did Gabler's changes overturn Joyce's last revisions, but in another four hundred places Gabler failed to follow any manuscript whatever, making nonsense of his own premises. Kidd accused Gabler of unnecessarily changing Joyce's spelling, punctuation, use of accents, and all the small details he claimed to have been restoring. Instead, Gabler was actually following printed editions such as that of 1932, not the manuscripts. More sensationally, Gabler was found to have made genuine blunders, the most famous being his changing the name of the real-life Dubliner Harry Thrift to 'Shrift' and cricketer Captain Buller to 'Culler' on the basis of handwriting irregularities in the extant manuscript. (These "corrections" were undone by Gabler in 1986.) Kidd stated that many of Gabler's errors resulted from Gabler's use of facsimiles rather than original manuscripts.

In December 1988, Charles Rossman's "The New Ulysses: The Hidden Controversy" for the New York Review revealed that Gabler's own advisers felt too many changes were being made, but that the publishers were pushing for as many alterations as possible. Then Kidd produced a 174-page critique that filled an entire issue of the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, dated the same month. This "Inquiry into Ulysses: The Corrected Text" was the next year published in book format and on floppy disk by Kidd's James Joyce Research Center at Boston University. Gabler and others rejected Kidd's critique, and the scholarly community remains divided.

Gabler edition dropped; publishers revert to 1960/61 editions

In 1990, Gabler's American publisher Random House, after consulting a committee of scholars,[19] replaced the Gabler edition with its 1961 version, and in the United Kingdom the Bodley Head press revived its 1960 version. In both the UK and USA, Everyman's Library also republished the 1960 Ulysses. In 1992, Penguin dropped Gabler and reprinted the 1960 text. The Gabler version remained available from Vintage International. Reprints of the 1922 first edition are also now widely available, largely due to the expiration of the copyright for that edition in the United States.

While much ink has been spilt over the faults and theoretical underpinnings of the Gabler edition, the long-awaited Kidd edition has yet to be published, as of 2015. In 1992 W. W. Norton announced that a Kidd edition of Ulysses was to be published as part of a series called "The Dublin Edition of the Works of James Joyce". This book had to be withdrawn, however, when the Joyce estate objected. The estate refused to authorise any further editions of Joyce's work for the immediate future, but signed a deal with Wordsworth Editions to bring out a bargain version of the novel in January 2010, ahead of copyright expiration in 2012.[20][21]

Literary significance and critical reception

In a review in The Dial, T. S. Eliot said of Ulysses: "I hold this book to be the most important expression which the present age has found; it is a book to which we are all indebted, and from which none of us can escape." He went on to assert that Joyce was not at fault if people after him did not understand it: "The next generation is responsible for its own soul; a man of genius is responsible to his peers, not to a studio full of uneducated and undisciplined coxcombs."[22] The book has its critics; Virginia Woolf stated that "Ulysses was a memorable catastrophe—immense in daring, terrific in disaster."[23]

| "What is so staggering about Ulysses is the fact that behind a thousand veils nothing lies hidden; that it turns neither toward the mind nor toward the world, but, as cold as the moon looking on from cosmic space, allows the drama of growth, being, and decay to pursue its course." |

| —Carl Jung [24] |

Ulysses has been called "the most prominent landmark in modernist literature", a work where life's complexities are depicted with "unprecedented, and unequalled, linguistic and stylistic virtuosity".[25] That style has been stated to be the finest example of the use of stream-of-consciousness in modern fiction, with the author going deeper and farther than any other novelist in handling interior monologue.[26] This technique has been praised for its faithful representation of the flow of thought, feeling, mental reflection, and shifts of mood.[27] Critic Edmund Wilson noted that Ulysses attempts to render "as precisely and as directly as it is possible in words to do, what our participation in life is like—or rather, what it seems to us like as from moment to moment we live."[28] Stuart Gilbert said that the "personages of Ulysses are not fictitious",[29] but that "these people are as they must be; they act, we see, according to some lex eterna, an ineluctable condition of their very existence".[30] Through these characters Joyce "achieves a coherent and integral interpretation of life".[30]

Joyce uses metaphors, symbols, ambiguities, and overtones which gradually link themselves together so as to form a network of connections binding the whole work.[27] This system of connections gives the novel a wide, more universal significance, as "Leopold Bloom becomes a modern Ulysses, an Everyman in a Dublin which becomes a microcosm of the world."[31] Eliot described this system as the "mythic method": "a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history".[32]

In April 2013 the Central Bank of Ireland issued a silver €10 commemorative coin in honour of Joyce that misquoted a famous line from the novel,[33] despite being warned on at least two occasions by the Department of Finance over difficulties with copyright and design.[34]

Censorship

Written over a seven-year period from 1914 to 1921, the novel was serialised in the American journal The Little Review from 1918 to 1920,[35] when the publication of the Nausicaä episode led to a prosecution for obscenity.[36] In 1919, sections of the novel also appeared in the London literary journal, The Egoist, but the novel itself was banned in the United Kingdom until the 1930s.[37] The novel was first published in its entirety by Sylvia Beach in February 1922, in Paris.[38]

The 1920 prosecution in the US was brought after The Little Review serialised a passage of the book dealing with the main character masturbating. Legal historian Edward de Grazia has argued that few readers would have been fully aware of the orgasmic experience in the text, given the metaphoric language.[39] Irene Gammel extends this argument to suggest that the obscenity allegations brought against The Little Review were influenced by the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's more explicit poetry, which had appeared alongside the serialization of Ulysses.[40] The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, which objected to the book's content, took action to attempt to keep the book out of the United States. At a trial in 1921 the magazine was declared obscene and, as a result, Ulysses was effectively banned in the United States. Throughout the 1920s, the United States Post Office Department burned copies of the novel.[41]

In 1933, the publisher Random House and lawyer Morris Ernst arranged to import the French edition and have a copy seized by customs when the ship was unloaded, which it then contested. In United States v. One Book Called Ulysses, U.S. District Judge John M. Woolsey ruled on 6 December 1933 that the book was not pornographic and therefore could not be obscene,[42] a decision that was called "epoch-making" by Stuart Gilbert.[43] The Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the ruling in 1934.[44] The US therefore became the first English-speaking country where the book was freely available. Although Ulysses was never banned in Ireland, neither was it available there.[38][45]

Media adaptations

Theatre

Ulysses in Nighttown, based on Episode 15 ("Circe"), premiered off-Broadway in 1958, with Zero Mostel as Bloom; it debuted on Broadway in 1974.

In 2006, playwright Sheila Callaghan's Dead City, a contemporary stage adaptation of the book set in New York City, and featuring the male figures Bloom and Dedalus re-imagined as female characters Samantha Blossom and Jewel Jupiter, was produced in Manhattan by New Georges.[46]

In 2013, a new stage adaptation of the novel, Gibraltar, was produced in New York by the Irish Repertory Theatre. It was written by and starred Patrick Fitzgerald and directed by Terry Kinney. This two-person play focused on the love story of Bloom and Molly, played by Cara Seymour.[47]

Film

In 1967, a film version of the book was directed by Joseph Strick. Starring Milo O'Shea as Bloom, it was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.

In 2003, a movie version Bloom was released starring Stephen Rea and Angeline Ball.

Television

In 1988, a documentary, the episode "James Joyce's Ulysses" in a series titled The Modern World: Ten Great Writers, was shown on Channel 4, where some of the most famous scenes from the novel were dramatised. David Suchet played Leopold Bloom.[48]

Audio

On Bloomsday 1982, RTÉ, Ireland's national broadcaster, aired a full-cast, unabridged, dramatised radio production of Ulysses,[49] that ran uninterrupted for 29 hours and 45 minutes. It has been commercially released as a boxed set of 32 CDs, and as an MP3 set on three CDs.

BBC Radio broadcast a highly abridged dramatisation of Ulysses read by Sinéad Cusack, James Greene, Stephen Rea, Norman Rodway, and others in 1993.[50] This performance had a running time of 5 hours and 50 minutes.

The unabridged text of Ulysses has been performed by Jim Norton, with Marcella Riordan. This recording was released by Naxos Records on 22 audio CDs in 2004. It follows an earlier abridged recording with the same actors.[50]

On Bloomsday 2010, author Frank Delaney launched a series of short weekly podcasts called Re:Joyce that take listeners through Ulysses page-by-page discussing its allusions, historical context and references.[51]

BBC Radio 4 aired a new nine-part adaptation dramatised by Robin Brooks and produced/directed by Jeremy Mortimer, and starring Stephen Rea as the Narrator, Henry Goodman as Leopold Bloom, Niamh Cusack as Molly Bloom and Andrew Scott as Stephen Dedalus, for Bloomsday 2012, beginning on 16 June 2012.[52]

Music

The song "ReJoyce", by Grace Slick (originally released on Jefferson Airplane's 1967 album After Bathing at Baxter's), may be taken as a condensed (and fragmentary) musical evocation of Molly Bloom's soliloquy. While the song includes allusions and themes not obviously related, clear references are made to numerous characters and situations from the novel. Notably, while Molly's soliloquy in the book ends in the affirmative, Grace's "Molly", having mused over the conditions of her life in a way similar to Joyce's, concludes with the stoically despairing "it all falls apart."

The song "Flower of the Mountain" by Kate Bush (originally the eponymous track off The Sensual World) sets to music the end of Molly Bloom's soliloquy.[53]

The Joyce novel is mentioned in the lyrics of the title track of Ulysses, a 2014 album by Canadian indie rock band Current Swell. The album cover art is also an homage to the first edition cover of the book. The novel is also directly alluded to by indie folk singer Mason Jennings in his song entitled "Ulysses", on his 2004 album Use Your Voice.

Prose

Jacob Appel's novel, The Biology of Luck (2013), is a retelling of Ulysses set in New York City. The novel features an inept tour guide, Larry Bloom, whose adventures parallel those of Leopold Bloom through Dublin.

Notes

- ↑ Harte, Tim (Summer 2003). "Sarah Danius, The Senses of Modernism: Technology, Perception, and Aesthetics". Bryn Mawr Review of Comparative Literature 4 (1). Retrieved 2001-07-10. (review of Danius book).

- ↑ Beebe (1971), p. 176.

- ↑ Kiberd, Declan (16 June 2009). "Ulysses, modernism's most sociable masterpiece". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ↑ Keillor, Garrison, "The Writer's Almanac", 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Vora, Avinash (20 October 2008). "Analyzing Ulysses". Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- ↑ "100 Best Novels". Random House. 1999. Retrieved 2007-06-23. This ranking was by the Modern Library Editorial Board of authors and critics; readers ranked it 11th. Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was ranked third by the board.

- ↑ Gorman (1939), p. 45.

- ↑ Jaurretche, Colleen (2005). Beckett, Joyce and the art of the negative. European Joyce studies 16. Rodopi. p. 29. ISBN 978-90-420-1617-0. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- ↑ Budgen (1972), p.

- ↑ Borach (1954), p. 325.

- ↑ Ellmann (1982), p. 265.

- ↑ "The bookies' Booker...". The Observer (London). 5 November 2000. Retrieved 2002-02-16.

- ↑ Text of Ulysses; search for "I.N.R.I."

- ↑ Hefferman, James A. W. (2001) Joyce’s Ulysses. Chantilly, VA: The Teaching Company LP.

- 1 2 McCarthy, Patrick A., "Joyce's Unreliable Catechist: Mathematics and the Narrative of 'Ithaca'", ELH, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Autumn 1984), pp. 605-606, quoting Joyce in Letters From James Joyce. A famous example is Joyce's apparent rendering of the year 1904 into the impossible Roman numeral MXMIV (p. 669 of the 1961 Modern Library edition)

- ↑ Robert McAlmon biography.

- ↑ Dalton, pp. 102, 113

- 1 2 3 4 Kidd, John (June 1988). "The Scandal of Ulysses". New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ↑ McDowell, Edwin, "Corrected 'Ulysses' Sparks Scholarly Attack", The New York Times, 15 June 1988

- ↑ Max, D.T. (19 June 2006). "The Injustice Collector". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ↑ Battles, Jan (9 August 2009). "Budget Ulysses to flood the market". The Sunday Times (London). Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ Eliot, T. S. (1975). "'Ulysses', Order and Myth". In Selected Prose of T.S. Eliot (London: Faber and Faber, 1975), 175.

- ↑ The Concise Cambridge History of English Literature, Sampson G. Churchill

- ↑ Jung, Carl. Ulysses: A Monologue. Translation by W.S. Dell of Jung’s Wirklichkeit der Seele, published in Nimbus, vol. 2, no. 1, June–August 1953.

- ↑ The New York Times guide to essential knowledge

- ↑ History of English literature, N Jayapalan. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 2001

- 1 2 Blamires, Henry, Short History of English literature

- ↑ Paul Grey, "The Writer James Joyce". Time magazine

- ↑ Gilbert (1930), p. 21.

- 1 2 Gilbert (1930), p. 22.

- ↑ Routledge History of Literature in English

- ↑ Armstrong, Tim (2005). Modernism: A Cultural History, p. 35. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-7456-2982-7.

- ↑ "Error in Ulysses line on special €10 coin issued by Central Bank". RTÉ News. 10 April 2013.

- ↑ "Bank alerted to Joyce coin risk". Evening Herald. 25 May 2013.

- ↑ The Little Review at The Modernist Journals Project (Searchable digital edition of volumes 1–9: March 1914 – Winter 1922)

- ↑ Ellmann, Richard (1982). James Joyce. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 502–04. ISBN 0-19-503103-2.

- ↑ McCourt (2000); p. 98.

- 1 2 "75 Years Since First Authorised American Ulysses!". Dublin: The James Joyce Center (2006).

- ↑ De Grazia, Edward. Girls Lean Back Everywhere: The Law of Obscenity and the Assault on Genius. New York: Vintage (1992); p. 10.

- ↑ Gammel, Irene. Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (2002); pp. 252-53.

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn. (2011). "Books: A Living History." Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications; p. 200; ISBN 978-1606060834.

- ↑ United States v. One Book Called "Ulysses", 5 F.Supp. 182 (S.D.N.Y. 1933).

- ↑ "Ulysses (first American edition)". James Joyce, Ulysses: The Classic Text: Traditions and Interpretations. University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. 2002. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses by James Joyce, 72 F.2d 705 (2nd Cir. 1934)

- ↑ "Ireland set for festival of Joyce" BBC, 11 June 2004. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ↑ Robertson, Campbell (16 June 2006). "Playwright of 'Dead City' Substitutes Manhattan for Dublin". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ "Gibraltar", IrishRep.org, New York: Irish Repertory Theatre (2013). Retrieved on 2013-12-15 from http://www.irishrep.org/gibraltar.html.

- ↑ "The Modern World: Ten Great Writers: James Joyce's 'Ulysses'". IMDb. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ↑ "Reading Ulysses". RTÉ.ie. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- 1 2 Williams, Bob. "James Joyce's Ulysses". the modern world. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ↑ "Frank Delaney: Archives". Blog.frankdelaney.com. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- ↑ "James Joyce's Ulysses". BBC Radio. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ↑ Kellogg, Carolyn (6 April 2011). "After 22 years, Kate Bush gets to record James Joyce". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

References

- Beebe, Maurice (Fall 1972). "Ulysses and the Age of Modernism". James Joyce Quarterly (University of Tulsa) 10 (1): 172–88.

- Borach, Georges. Conversations with James Joyce, translated by Joseph Prescott, College English, 15 (March 1954)

- Burgess, Anthony. Here Comes Everybody: An Introduction to James Joyce for the Ordinary Reader (1965); also published as Re Joyce.

- Burgess, Anthony. Joysprick: An Introduction to the Language of James Joyce (1973).

- Budgen, Frank. James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, (1960).

- Budgen, Frank (1972). James Joyce and the making of 'Ulysses', and other writings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211713-0.

- Dalton, Jack. The Text of Ulysses in Fritz Senn, ed. New Light on Joyce from the Dublin Symposium. Indiana University Press (1972).

- Ellmann, Richard. James Joyce. Oxford University Press, revised edition (1983).

- Ellmann, Richard, ed. Selected Letters of James Joyce. The Viking Press (1975).

- Gilbert, Stuart. James Joyce's Ulysses: A study, Faber and Faber (1930).

- Gorman, Herbert. James Joyce: A Definitive Biography (1939).

- McCourt, John (2000). James Joyce: A Passionate Exile. London: Orion Books Ltd. ISBN 0-7528-1829-5.

Further reading

- Arnold, Bruce. The Scandal of Ulysses: The Life and Afterlife of a Twentieth Century Masterpiece. Rev. ed. Dublin: Liffey Press, 2004. ISBN 1-904148-45-X.

- Attridge, Derek, ed. James Joyce's Ulysses: A Casebook. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP, 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-515830-4.

- Benstock, Bernard. Critical Essays on James Joyce's Ulysses. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1989. ISBN 978-0-8161-8766-9.

- Birmingham, Kevin. The Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce's Ulysses. London: Head of Zeus Ltd., 2014. ISBN 9781101585641

- Duffy, Enda, The Subaltern Ulysses. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8166-2329-5.

- Ellmann, Richard. Ulysses on the Liffey. New York: Oxford UP, 1972. ISBN 978-0-19-519665-8.

- French, Marilyn. The Book as World: James Joyce's Ulysses. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1976. ISBN 978-0-674-07853-6.

- Gillespie, Michael Patrick and A. Nicholas Fargnoli, eds. Ulysses in Critical Perspective. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006 . ISBN 978-0-8130-2932-0.

- Goldberg, Samuel Louis. The Classical Temper: A Study of James Joyce's Ulysses. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1961 and 1969.

- Henke, Suzette. Joyce's Moraculous Sindbook: A Study of Ulysses. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 1978. ISBN 978-0-8142-0275-3.

- Kiberd, Declan. Ulysses and Us: the art of everyday living. London: Faber and Faber, 2009 ISBN 978-0-571-24254-2

- Killeen, Terence. Ulysses Unbound: A Reader's Companion to James Joyce's Ulysses. Bray, County Wicklow, Ireland: Wordwell, 2004. ISBN 978-1-869857-72-1.

- McKenna, Bernard. James Joyce's Ulysses: A Reference Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-313-31625-8.

- Murphy, Niall. A Bloomsday Postcard. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1-84351-050-5.

- Norris, Margot. A Companion to James Joyce's Ulysses: Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays From Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Boston: Bedford Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0-312-21067-0.

- Rickard, John S. Joyce's Book of Memory: The Mnemotechnic of Ulysses. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0822321583.

- Schutte, William M. James Index of Recurrent Elements in James Joyce's Ulysses. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8093-1067-8.

- Vanderham, Paul. James Joyce and Censorship: The Trials of Ulysses. New York: New York UP, 1997. ISBN 978-0-8147-8790-8.

- Weldon, Thornton. Allusions in Ulysses: An Annotated List. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968 and 1973. ISBN 978-0-8078-4089-4.

List of Editions in print

Facsimile texts of the manuscript

- Ulysses, A three volume, hardcover, with slip-case, facsimile copy of the only complete, handwritten manuscript of James Joyce's Ulysses. Three volumes. Quarto. Critical introduction by Harry Levin. Bibliographical preface by Clive Driver. The first two volumes comprise the facsimile manuscript, while the third contains a comparison of the manuscript and the first printings, annotated by Clive Driver. These volumes were published in association with the Philip H. &. A.S.W. Rosenbach Foundation (now known as the Rosenbach Museum & Library), Philadelphia. New York: Octagon Books (1975).

Serial text published in the Little Review, 1918-1920

- The Little Review Ulysses, edited by Mark Gaipa, Sean Latham and Robert Scholes, Yale University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-300-18177-7

Facsimile texts of the 1922 first edition

- Ulysses, The 1922 Text, with an introduction and notes by Jeri Johnson, Oxford University Press (1993). A World Classics paperback edition with full critical apparatus. ISBN 0-19-282866-5

- Ulysses: A Facsimile of the First Edition Published in Paris in 1922, Orchises Press (1998). This hardback edition closely mimics the first edition in binding and cover design. ISBN 978-0-914061-70-0

- Ulysses: With a new Introduction by Enda Duffy - An unabridged republication of the original Shakespeare and Company edition, published in Paris by Sylvia Beach, 1922, Dover Publications (2009). Paperback. ISBN 978-0-486-47470-0

Based on the 1932 Odyssey Press edition

- Ulysses, Wordsworth Classics (2010). Paperback. Introduction by Cedric Watts. ISBN 978-1-840-22635-5

Based on the 1939 Odyssey Press edition

- Ulysses, Alma Classics (2012), with an introduction and notes by Sam Slote, Trinity College, Dublin. Hardback. ISBN 978-1-84749-217-3

Based on the 1960 Bodley Head/1961 Random House editions

- Ulysses, Vintage International (1990). Paperback. ISBN 978-0-679-72276-2

- Ulysses: Annotated Student's Edition, with an introduction and notes by Declan Kiberd, Penguin Twentieth Century Classics (1992). Paperback. ISBN 978-0-141-18443-2

- Ulysses: The 1934 Text, As Corrected and Reset in 1961, Modern Library (1992). Hardback. With a foreword by Morris L. Ernst. ISBN 978-0-679-60011-4

- Ulysses, Everyman's Library (1997). Hardback. ISBN 978-1-85715-100-8

- Ulysses, Penguin Modern Classics (2000). Paperback. With an introduction by Declan Kiberd. ISBN 978-0-14118-280-3

Based on the 1984 Gabler edition

- Ulysses: The corrected text, Edited by Hans Walter Gabler with Wolfhard Steppe and Claus Melchior, and a new preface by Richard Ellmann, Vintage International (1986). This follows the disputed Garland Edition. ISBN 978-0-39474-312-7

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ulysses (novel) |

- Ulysses at Project Gutenberg

- Ulysses online audiobook.

-

Ulysses public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Ulysses public domain audiobook at LibriVox - The Little Review at The Modernist Journals Project includes all 23 serialised instalments of Ulysses

- Schemata of Ulysses

- The text of Joseph Collins's 1922 New York Times review of Ulysses

- Publication history of Ulysses

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|