Harlem riot of 1964

On Thursday, July 16, 1964, James Powell was shot and killed by police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan. The second bullet of three fired by Lieutenant Gilligan killed the 15-year-old African American in front of his friends and about a dozen other witnesses. The incident immediately rallied about 300 students from a nearby school who were informed by the principal. This incident set off six consecutive nights of rioting that affected the New York City neighborhoods of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant. In total, 4,000 New Yorkers participated in the riots which led to attacks on the New York City Police Department, vandalism, and looting in stores. At the end of the conflict, reports counted one dead rioter, 118 injured, and 465 arrested. It is said that the Harlem race riot of 1964 is the precipitating event for riots in July and August in cities such as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Rochester, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Jersey City, New Jersey; Paterson, New Jersey; and Elizabeth, New Jersey.

Background

Investigation

The events of the Harlem riot of 1964 are based on the writings of two newspaper reporters, Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan. They assembled testimonies from other reporters and from residents of each of the boroughs, and gave testimony of their presence at the riots.[1][2]

Consistently annoyed by the presence of young students on his stoops, Patrick Lynch, the superintendent of three apartment houses in Yorkville, at the time a predominately working-class white area on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, voluntarily hosed down the black students while insulting them according to them: “Dirty niggers, I'll wash you clean”;[3] this statement had been denied by Lynch. The angry wet black students started to pick up bottles and garbage-can lids and threw them at the superintendent. This immediately drew the attention of three Bronx boys, including James Powell. Lynch then retreated to the inside of the building pursued by Powell, who according to a witness, “didn't stay two minutes.”[4] As Powell exited the vestibule, off-duty police Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan, who witnessed the scene from a nearby shop, ran to the scene and shot at the 15 year-old James Powell three times. The first round, said to be the warning shot, hit the apartment's window. The next shot hit Powell in the right forearm reaching the main artery just above the heart. The bullet lodged in his lungs. Finally, the last one went through his abdomen and out his back. The autopsy concluded on the fatality of the chest wound in almost any circumstance. However, the pathologist said that Powell could have been saved suffering only the abdominal perforation with a fast response of the ambulance. The sequence of events is still unclear on many aspects such as the spacing of the shots and, crucially, Powell's possession of a knife.[1][2]

Lieutenant Gilligan's version of the events

To the sound of broken glass, Gilligan ran to the apartment building holding his badge and gun. He first yelled, “I'm a police lieutenant. Come out and drop it.”[5] He then fired the warning shot as he saw Powell raising the knife. With his gun, Gilligan blocked Powell's second attack deflecting the knife to his arm. The apparent attack led Gilligan to fire a third round that killed the young Powell.[1][2]

Witnesses's version of the events

In opposition, witnesses saw Powell ran into the building not carrying any knife. As he exited the vestibule, some said he was laughing until the lieutenant shot him. From the point of view of the French class which according to New York Times' reporter, Theodore Jones, “have had the best view of the ensuing tragedy”;[6] when Gilligan pulled his gun, the young Powell threw up his right arm, not holding a knife but as a defensive gesture.[1][2]

The most controversial episode remains the testimony of Cliff Harris, Powell's Bronx friend, interviewed the day following the death of James Powell. On that morning, they, James Powell, Cliff Harris and Carl Dudley, left the Bronx around 7:30 A.M. Powell carried two knives on that day which he gave to each of his friends to be held for him. On the scene he asked for the knives back. Upon Dudley's refusal he asked Cliff who asked him why he wanted it back? and then handed it over.[1][2]

The knife which was not seen on the crime scene at the moment of the incident was found by a teacher reported school principal Francke. The knife was situated in the gutter at about eight feet of the body

People

Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan

Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan served seventeen years in the Police Department and had a few notable entries to his record. Before the Powell incident, he had shot two other men. One of those men was trying to push him off a roof and the other much younger was looting cars in front of his apartment. Citations in the New York Daily News reported that Gilligan had disarmed suspects in the past. In addition, he rescued women and children from a fire, stopped a man from a suicidal jump as well as used mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to revive a woman who had attempted suicide. Physically Gilligan was a man of six feet tall.[1][2]

James Powell

James Powell was a ninth grader in the Bronx attending summer school at the Robert F. Wagner, Sr., Junior High School on East 76th Street. After his father's death, neighbours said the young boy had become “a little wild”.[7] He had four minor altercations with the law: twice attempted to board a subway or bus without paying, broke a car window and attempted robbery from which he was cleared. Physically he was five feet, six inches and weighed 122 pounds.[1][2]

Location

In the early 1900s appeared the first signs of resurgence in the north of Manhattan. After the construction of new subway routes that go as far as 145th street, speculators and real estate agencies took advantage of this opportunity and invested large sums of money in what is now called Harlem. Houses were bought and then sold over and over to a much higher price, upbringing the neighbourhood for high-income households. By the year 1905, too many habitations had been constructed and many stayed uninhabited which led landlords to compete with each other lowering rents. To avoid the upcoming total financial destruction of the area, many housing buildings opened up to Black Americans. The next step to the creation of a black neighborhood was strengthened by the ever-increasing migration of Blacks from southern states which resulted in the founding of the Afro-American Realty Company opening more and more homes for the black community. The "Negro" churches took over Harlem's development after the fall of the Afro-American Realty, being the most stable and prosperous black institution of the now segregated area. They made their profit by selling properties at high price while relocating the neighborhood uptown. Consequently, the Church is the reason why Harlem was so prolific in the 20th century. In the early 1920s, many Black American institution such as NAACP, Odd Fellows, The United Order of True Reformers started moving their headquarters to Harlem which, with the continuous migration of Blacks, received the name of “Greater Harlem.”[8][9]

The cultural aspect of Harlem was predominated by Jazz music and a very envious nightlife reserved for Whites. Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong were part of “Greater Harlem” [8] at the time. With its saturated concentration of Afro-American, public figures like Father Divine, Daddy Grace and Marcus Garvey started spreading their ideas of salvation for the negro community. After World War II, the rich portion of the “Harlem Negroes” moved to the suburbs. Tension within the neighborhood raised year after year between residents, welfare workers and policemen. In daylight, the neighborhood was quite charming, the architecture added a high-class cachet and children looked joyful playing in the streets. At night, it was quite the opposite. Homicides were six times more frequent than the average of New York City. Prostitution, junkies and muggers were part of Harlem's nightlife.[9]

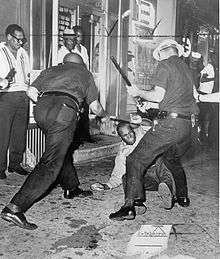

Rioting

Day 1: Thursday, July 16, 1964

Day 1 of the riot had been contained by 75 police officers. Briefly, it happened right after the shooting of James Powell and the Police Department were securing the crime scene from approximately 300 people, the majority of whom were students. The confrontations between students and policemen foreshadowed on the next morning protest.[1][2]

Day 2: Friday, July 17, 1964

On the morning after the shooting, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) showed up at the school nearby the scene. They demanded a civilian review board to discipline the police, but they were greeted by 50 officers holding nightsticks. 200 pickets, mainly whites and Puerto Ricans, were situated in front of the school by noon, chanting “Stop killer cops!”, “We want legal protection” and “End police brutality.”[1][2][10]

Day 3: Saturday, July 18, through early morning Sunday, July 19, 1964

On July 18, the temperature went up to 92 degrees in Central Park and much higher on the pavement. 250 persons attended James Powell's funeral under strict supervision of barricaded policemen. At the same time, another patrol was watching over a demonstration on the rising crime rate in Harlem. Both events ended peacefully with no incident. The CORE rally happened rather peacefully until the majority of the press corps had left. Paul L. Montgomery stayed behind; except for a UPI summer intern on his first field assignment, Montgomery worked alone for most of the evening and became the source of information for what is to follow. Reverend Nelson C. Dukes then called for action leading the march to the 28th precinct supported by Black Nationalist Edward Mills Davis and James Lawson. After meeting with Inspector Pendergast, the committee addressed the crowd, but it was already too late. The crowd began to throw bottles and debris at the police line. Soon the rioters took over rooftops which is said to have been the number one police's enemy at the time. Easily accessible, rooftops were in bad shape and bricks, tiles and mortar were used as weapons. The policemen rapidly secured the rooftops arresting CORE members. The rioters filled with emotion could not be controlled anymore and they continued to throw bottles which hit Michael Doris in the face; the first police officer to be injured during the Harlem riot of 1964. Subsequently, Inspector Pandergast instructed the force to clear the street after declaring that the crowd had become a disorderly gathering. By 10 P.M., a thousand people had assembled at the intersection of the Seventh Avenue and 125th Street. “Go home, go home”[11] shouted an officer in a way to disperse the crowd, but the crowd answered: “We are home, Baby.”[11] The Tactical Patrol Force arrived on site and were attacked by bricks flying from rooftops. They started to break the crowd into smaller mobs which created an uncontrollable chaos. The mobs started running away from the intersection, beating “Whities”, as they used to call the White American. The most violent mob went down to 123rd Street and could be followed the next morning by its destruction path. Around 10:30 P.M. a group of rioters stopped in front of the Theresa hotel where a Molotov cocktail was thrown on a police car injuring one officer. Police officers received permission to draw their firearms and fired into the air to repel the aggressors from rooftops. Later TPF (Tactical Police Force) found one dead man due to the firing of a .38 caliber. It was after the first round had been fired that reporters were sent back to Harlem. Shortly after the force started firing, an ordnance truck from the Bronx was loaded with ammunition to support the officers. Many Harlemites, exiting the subway and bars, got caught up in the riot and later realized that they were being pursued by the police. The chaos finally ended at 8 o'clock in the morning on Lenox Street, where what was left of the mobs had regrouped and then were dispersed by massive reinforcement. According to Inspector Pandergast's announcement, one rioter died, 12 policemen and 19 civilians were injured and 30 were arrested. Over 22 stores had been looted. The report of Pandergast was hotly contested by the hospital that counted 7 gunshot wounds and 110 persons who considered their injuries worth intensive care.[1][2]

CORE rally

A scheduled rally organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (or CORE) in the afternoon of Saturday, July 18 changed its focus upon the arrival of Louis Smith, a CORE field secretary. The rally had for objective to clarify on the missing of three civil right workers in Mississippi, thus looked over the shooting of James Powell as well as pointed out police brutality as a plague upon the Black community. The gathering seemed to end quietly leaving “the crowd excited, but not unruly.”[12] After most of the reporters had left, Judith Howell, a young high-school student and a member of the Bronx chapter of CORE climbed on a chair and said: “We got a civil rights bill and along with the bill we got Barry Goldwater and a dead black boy, This shooting of James Powell was murder!”[13] After her speech the cry was for action and was followed by Reverend Nelson C. Dukes from the Fountain Springs Baptist Church who, after his 20 minutes long speech, led the crowd to the 28th precinct supported by Black Nationalist Edward Mills Davis and James Lawson. Upon arrival, the police department was in motion and Inspector Pandergast accommodated the committee formed by Dukes, Charles Russell (East River CORE), Charles Taylor and Newton Sewell (Black Nationalist). Their only demand was the suspension of Lieutenant Gilligan.[1][2]

Day 4: Sunday, July 19, through Monday, July 20, 1964

Commissioner Murphy distributed a statement to every church in Harlem after the incident of Saturday night. He stated: “In our estimation, this is a crime problem and not a social problem!"[14] Later that day, Malcolm X, Black Nationalist Leader answered, “There are probably more armed Negroes in Harlem than in any other spot on earth” - “If the people who are armed get involved in this, you can bet they'll really have something on their hands.”[15] This feeling of hatred against whites and especially against the New York Police Department was present in the majority of the Black community. Blacks were actually threatening policemen as well as firemen in broad daylight throughout Sunday.[1][2]

The NYPD conceded the ineffectiveness of tactical techniques, such as mounted police and tear gas, which were having no actual effect on the rooftop threat. James L. Farmer, Jr., national director of CORE, who attended the riot, confirmed the assumption of police brutality and testified to seeing bullet holes in windows and walls of the Theresa Hotel. He also claimed Inspector Pandergast was at the origin of the riot.[1][2]

Meanwhile a meeting of the Black Citizens Council had taken place at the Mount Morris Presbyterian Church. The overall voice was for action. More precisely “Guerilla warfare!”,[16] but the vast majority agreed on thoughtful action. “If we must die, we must die scientifically.”[17] Bayard Rustin, engineer of the March on Washington and the New York's first school boycott, received cries of disapproval from the crowd and then decided to lead a crew of 75 volunteers to keep an outpost on the 125th Street and 8th Avenue, constituting an aide for teenagers and women in the closing riot. Other speakers at the rally tried to reason with the crowd to join in a peaceful protest, but the crowd exiting the church was an ugly one. The mob started to argue with two white reporters. An individual didn't want to be photographed and brought the crowd into a struggle, beating the two reporters.The police line on the sidewalk witnessed the scene but decided not to move or to intervene. Junius Griffin, a black reporter for The New York Times, appeared and managed to control the crowd and saved the two men. The mob moved to the Delany Funeral Home where a service for Powell's death had been scheduled for 8 P.M. At that point someone threw a bottle at the police and the police threw it back at the crowd. The riot had started once again. Bricks and bottles were falling from rooftops like rain from clouds. Bayard Rustin and other speakers were trying to convince the rioters to save their souls, but they were booed and the crowd shouted back at them: “Tom, Uncle Tom.”[18] After a Molotov cocktail had been thrown, some police lowered their guns and wounded two young men as they charged. The riot was scattered by midnight and grew out of proportion once again after some disturbance. Many Molotov Cocktails were used and one got into the second floor of a housing project. Firemen got to the fire quickly and brought a lady to the hospital. Two more young men were wounded by bullets and one policeman had a heart attack. The violence ended around 1.30 A.M. and reports counted 27 policemen and 93 civilians injured, 108 arrested and 45 stores looted. Hospitals however counted more than 200 entries in their registries.[1][2]

Day 5: Monday, July 20, through Tuesday Evening, July 21

The situation was quieter in the street of Harlem on Monday. Paul R. Screvane confirmed that a New York County grand jury would look into the murder of James Powell and at the same time, announced Mayor Wagner's hasty return.[1][2]

The riot started after the UN demonstration to protest terrorism and genocide committed against Black Americans. The events that followed greatly resembled those of the Sunday riot, although at the end of the night, a reinforcement call was made for Bedford-Stuyvesant, foreshadowing the growing social issue that it became.[1][2]

The Brooklyn CORE branch had prepared an all-day march for Monday in support of the rioters in Harlem. They protested the shooting of the young Powell and denounced police brutality against Harlemites. After blocking four main intersections of Bedford-Stuyvesant, the CORE members and Brooklynites assembled at Nostrand and Fulton where they set up a rally. As the speakers changed, the crowd became more emotional and was no longer paying attention to the rally. The police enforcement, which had kept a low profile in Bedford-Stuyvesant, suddenly called for reinforcements. CORE members tried to control the crowd and in a last attempt told them to go back home. At that point, a thousand people were standing on the street corner, infuriated and ready for action. Bottles were thrown and cops' heads were the target. To the sound of sirens and tires, the reinforcements arrived at their destination and the police charged the mob, making no apparent distinction between innocents and enemies. The tumult stopped a little after 7 A.M. and CORE announced a new rally in not less than twelve hours.[1][2]

Day 6: Tuesday night, July 21, through Wednesday, July 22

Tuesday in Brooklyn started by a meeting of all V.I.P. of Black organizations with Captain Edward Jenkins, commanding officer of the 79th precinct, at the Bedford YMCA. Over the day, they looked at plausible explanations of the riot's cause and also at Lieutenant Gilligan's case.[1][2]

That night, CORE's demonstration was replaced by Black Nationalist speakers who, every week, were present at this very same spot. The difference is that on a regular Tuesday there was no crowd to listen to them. Tuesday, July 21, was certainly an opportunity out of the ordinary for the Black Nationalist Party to spread its ideas to the Black community. After a 20-minute speech, the crowd started to be agitated even though the speaker, becoming worried about the situation, changed the tone of what he was saying and tried to convince the crowd to remain calm. The riot started again and police charged the mob while angry rioter threw bottles and debris at them. Everything was under control by 2 A.M. on Wednesday.[1][2]

On Wednesday night, a troop of mounted police was set at the four corners of the intersection of Fulton and Nostrand. The buildings were lower and the street wider, reducing the risk of using horses for crowd control. A sound truck with a NAACP logo had been driving down the streets of Bedford-Stuyvesant during the day and parked where the Black Nationalists had set a podium on the day before. When the crowd that had formed in front of the truck was of a reasonable size, Fleary, one of the NAACP workers, addressed the crowd. He claimed that Bedford-Stuyvesant was a “community of law”.[19] Furthermore he insisted that riots weren't how they were going to get what they wanted. The mob seemed to generally agree with him until a group of men, among them four were wearing a green beret, appeared across the street and approached the sound truck. They started to rock the truck while the mob got more and more agitated. Fleary will remain the only community leader affirming the presence of external agitators. When Fleary lost the control of the microphone, the police charge to rescue the NAACP crew had the effect of starting another riot.[1][2]

Aftermath

Statistics vary but it is estimated that 500 persons were injured, one man died and 465 men and women were arrested.[20] Property damage was estimated to be between $500,000 and $1 million.

In September, Gilligan was cleared of any wrongdoing by a grand jury and charges were dropped. He always maintained Powell had lunged at him with a knife.[20]

Lloyd Sealy was named commander of the 28th Precinct; he was the NYPD's first African American precinct commander.[21]

Project Uplift (1965)

Project Uplift was a major short-term program of the Johnson administration's Great Society suite of social welfare programs.[22] An experimental anti-poverty program in Harlem, New York, in the summer of 1965, it was intended to prevent the recurrence of the riots that had hit the community the summer before.[22]

Thousands of young Harlemites were employed in a variety of jobs intended in the short run to keep them busy and, in the long run, to give them skills and opportunities to break out of poverty.[22] Young people were employed running a summer camp, planting trees, repairing damaged buildings, and printing a newspaper. Projects included a Project Uplift theater program, run by LeRoi Jones, and a dance program.[22]

See also

- Harlem riot of 1935, trouble that began after rumors circulated that a young child had been severely beaten by a shopkeeper.

- Harlem riot of 1943, disturbances that began after a policeman shot and wounded a black U.S. Army soldier.

- The Progressive Labor Party, whose members were accused by New York City law enforcement of leading the 1964 riots.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Abu-Lughod, Janet L. (2007). Race, space, and riots in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 4.

- ↑ Abu-Lughod, Janet L. (2007). Race, space, and riots in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 14.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 9.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 5.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 3.

- 1 2 Meister, Richard J. (1971; 1972). The Black ghetto: promised land or colony?. Lexington, Mass: Heath. p. 58. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 Meister, Richard J. (1971; 1972). The Black ghetto: promised land or colony?. Lexington, Mass.: Heath. ISBN 0669742600. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 13.

- 1 2 Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 50.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 45.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 44.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 65.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 67.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 74.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 75.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 80.

- ↑ Fred C. Shapiro and James W. Sullivan (1964). Race riots, New York, 1964. New York: Crowell. p. 162.

- 1 2 Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton. Preview this book Encyclopedia of American race riots. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ↑ New York City Police Museum: A History of African Americans in the NYPD

- 1 2 3 4 Poverty and Politics in Harlem, Alphonso Pinkney & Roger Woock, College & University Press Services, Inc., 1970, p.82

Further reading

- RW Apple, "Police Defend the Use of Gunfire in Controlling Riots in Harlem", The New York Times, 7/21/64.

- Peter Kihss, "Screvane Links Reds to Rioting", The New York Times, 7/22/64; and letters in response on 7/24/64.

- Barbara Benson, Letter to Editor, "Why Harlem Negroes Riot", The New York Times, 7/22/64.

- "'Casualty' List in Battle of Harlem", Amsterdam News, 7/25/64

- "Injured in the Battle of Harlem", Amsterdam News, 7/25/64

- George Barner, "The Negro Cop in a Race Riot", Amsterdam News, 7/25/64

- "The Total in Riots", Amsterdam News, 8/l/64.

- "Rioting follows a common pattern", The New York Times, 8/30/64.

- A history of the Congress of Racial Equality in New York City