Harbin

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Harbin (![]() [Listen]) is the capital and largest city of Heilongjiang province, China.[5] Holding sub-provincial administrative status,[6] Harbin has direct jurisdiction over nine metropolitan districts, two county-level cities and seven counties. Harbin is the eighth most populous Chinese city and the most populous city in Northeast China.[7] According to the 2010 census, the built-up area made of seven out of nine urban districts (all but Shuangcheng and Acheng not urbanized yet) had 5,282,093 inhabitants, while the total population of the sub-provincial city was up to 10,635,971.[4] Harbin serves as a key political, economic, scientific, cultural and communications hub in Northeast China, as well as an important industrial base of the nation.[8]

[Listen]) is the capital and largest city of Heilongjiang province, China.[5] Holding sub-provincial administrative status,[6] Harbin has direct jurisdiction over nine metropolitan districts, two county-level cities and seven counties. Harbin is the eighth most populous Chinese city and the most populous city in Northeast China.[7] According to the 2010 census, the built-up area made of seven out of nine urban districts (all but Shuangcheng and Acheng not urbanized yet) had 5,282,093 inhabitants, while the total population of the sub-provincial city was up to 10,635,971.[4] Harbin serves as a key political, economic, scientific, cultural and communications hub in Northeast China, as well as an important industrial base of the nation.[8]

Harbin, which was originally a Manchu word meaning "a place for drying fishing nets",[8] grew from a small rural settlement on the Songhua River to become one of the largest cities in Northeast China. Founded in 1898 with the coming of the Chinese Eastern Railway, the city first prospered as a region inhabited by an overwhelming majority of the immigrants from the Russian Empire.[9]

Having the most bitterly cold winters among major Chinese cities, Harbin is heralded as the Ice City for its well-known winter tourism and recreations.[10] Harbin is notable for its beautiful ice sculpture festival in the winter.[11] Besides being well known for its historical Russian legacy, the city serves as an important gateway in Sino-Russian trade today, containing a sizable population of Russian diaspora.[12] In the 1920s, the city was considered China's fashion capital since new designs from Paris and Moscow reached here first before arriving in Shanghai.[13] The city has been voted "China Top Tourist City" by China National Tourism Administration in 2004.[8] On 22 June 2010, Harbin was appointed a UNESCO "City of Music" as part of the Creative Cities Network.[14]

History

Early history

Human settlement in Harbin area dates from at least 2200 BC during the late Stone Age. Wanyan Aguda, the founder and first emperor of Jin dynasty from 1115 to 1123, was born in the Jurchen Wanyan tribes who resided near the Ashi River in this region.[15] In 1115 CE, Aguda established Jin's capital Shangjing (Upper Capital) Huining Fu in today's Acheng District of Harbin.[16] After Aguda's death, the new emperor Wanyan Sheng ordered to build a new city on uniform plan. The planning and construction emulated major Chinese cities, in particular Bianjing (Kaifeng), although the Jin capital was smaller than its Northern Song prototype.[17] Huining Fu served as the first superior capital of the empire until the capital was moved to Yanjing (now Beijing) in 1153 by Wanyan Liang (the fourth emperor of Jin Dynasty).[18] Liang even went so far as to destroy all palaces in his former capital in 1157.[18] Wanyan Liang's successor Wanyan Yong (Emperor Shizong) restored the city and established it as a secondary capital in 1173.[19] Ruins of the Shangjing Huining Fu were discovered and excavated at about 2 km from present-day Acheng's central urban area.[16][20] The site of the old Jin capital ruins is a national historic reserve, and includes the Jin Dynasty History Museum. The museum is open to public and renovated in the late 2005.[20] Mounted statues of Aguda and his chief commander Wanyan Zonghan (also Nianhan) have been erected on the grounds of the museum.[21] Many of the artifacts found there are on display in nearby Harbin.

After the Mongol conquest of the Jin Empire, Huining Fu was abandoned. Building materials of Huining Fu's ruin was later exploited by the Manchus in the 1600s to build their new stronghold in Alchuka. The region of Harbin remained largely rural until the 1800s, with only over ten villages and about 30,000 people in today's urban districts of the city by the end of the 19th century.[22]

International city

A small village in 1898 grew into the modern city of Harbin.[23] Polish engineer Adam Szydłowski drew plans for the city following the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway, which the Russian Empire had financed.[9] The Russians selected Harbin as the base of their administration over this railway and the Chinese Eastern Railway Zone. The Chinese Eastern Railway extended the Trans-Siberian Railway: substantially reducing the distance from Chita to Vladivostok and also linking the new port city of Dalny (Dalian) and the Russian Naval Base Port Arthur (Lüshun).

During the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5), Russia used Harbin as its base for military operations in Northeastern China. Following Russia's defeat, its influence declined. Several thousand nationals from 33 countries, including the United States, Germany, and France moved to Harbin. Sixteen countries established consulates to serve their nationals, who established several hundred industrial, commercial and banking companies. Churches were rebuilt for Russian Orthodox, Ukrainian Orthodox, Lutheran/German Protestant, and Polish Catholic Christians. Chinese capitalists also established businesses, especially in brewing, food and textiles. Harbin became the economic hub of northeastern China and an international metropolis.[22]

Rapid growth of the city challenged the public healthcare system. The worst-ever recorded outbreak of pneumonic plague was spread to Harbin through the Trans-Manchurian railway from the border trade port of Manzhouli.[24] The plague lasted from late autumn of 1910 to the spring of 1911 and killed 1,500 Harbin residents (mostly ethnic Chinese), or about five percent of its population at the time.[25] This turned out to be the beginning of the large pneumonic plague pandemic of Manchuria and Mongolia which ultimately claimed 60,000 victims. In the winter of 1910, Dr. Wu Lien-teh (later the founder of Harbin Medical University) was given instructions from the Foreign Office, Peking, to travel to Harbin to investigate the plague. Dr. Wu asked for imperial sanction to cremate plague victims, as cremation of these infected victims turned out to be the turning point of the epidemic. The suppression of this plague pandemic changed medical progress in China. Bronze statues of Dr. Wu Lien-teh are built in Harbin Medical University to remember his contributions in promoting public health, preventive medicine and medical education.[26]

After the plague epidemic Harbin's population continued to increased sharply, especially inside the Chinese Eastern Railway Zone. In 1913 the Chinese Eastern Railway census showed its ethnic composition as: Russians – 34313, Chinese (that is, including Hans, Manchus etc.) – 23537, Jews – 5032, Poles – 2556, Japanese – 696, Germans – 564, Tatars – 234, Latvians – 218, Georgians – 183, Estonians – 172, Lithuanians – 142, Armenians – 124; there were also Karaims, Ukrainians, Bashkirs, and some Western Europeans. In total, 68549 citizens of 53 nationalities, speaking 45 languages.[27] Research shows that only 11.5 percent of all residents were born in Harbin.[28] By 1917, Harbin's population exceeded 100,000, with over 40,000 of them were ethnic Russians.[29]

After Russia's Great October Socialist Revolution in November 1917, more than 100,000 defeated Russian White Guards and refugees retreated to Harbin, which became a major center of White Russian émigrés and the largest Russian enclave outside the Soviet Union.[29] The city had a Russian school system, as well as publishers of Russian-language newspapers and journals. Russian 'Harbintsy'[30] community numbered around 120,000 at its peak in the early 1920s.[31] In the early 1920s, according to Chinese scholars' recent studies, over 20,000 Jews lived in Harbin.[32] After 1919, Dr. Abraham Kaufman played a leading role in Harbin's large Russian Jewish community.[33] The Republic of China discontinued diplomatic relations with Imperial Russia in 1920, so many Russians found themselves stateless. When the Chinese Eastern Railway and government in Beijing announced in 1924 that they agreed the railroad would only employ Russian or Chinese nationals, the emigrees were forced to announce their ethnic and political allegiance. Most accepted Soviet citizenship. The Chinese warlord Zhang Xueliang seized the Chinese Eastern Railway in 1929. Soviet military force quickly put an end to the crisis and forced the Nationalist Chinese to accept restoration of joint Soviet-Chinese administration of the railway.[34]

Japanese invasion period

Japan invaded Manchuria outright after the Mukden Incident in September 1931. After the Japanese captured Qiqihar in the Jiangqiao Campaign, the Japanese 4th Mixed Brigade moved toward Harbin, closing in from the west and south. Bombing and strafing by Japanese aircraft forced the Chinese army to retreat from Harbin. Within a few hours the Japanese occupation of Harbin was complete.[35]

With the establishment of the puppet state of Manchukuo, the pacification of Manchukuo began, as volunteer armies continued to fight the Japanese. Harbin became a major operations base for the infamous medical experimenters of Unit 731, who killed people of all ages and ethnicities. All these units were known collectively as the Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army.[36] The main facility of the Unit 731 was built in 1935 at Pingfang District, approximately 24 km (15 mi) south of Harbin urban area at that time.[37] Between 3,000 and 12,000 citizens including men, women, and children[38][39]—from which around 600 every year were provided by the Kempeitai[40]—died during the human experimentation conducted by Unit 731 at the camp based in Pingfang alone, which does not include victims from other medical experimentation sites.[41] Almost 70 percent of the victims who died in the Pingfang camp were Chinese, including both civilian and military.[42] Close to 30 percent of the victims were Russian.[43] Some others were South East Asians and Pacific Islanders, at the time colonies of the Empire of Japan, and a small number of the prisoners of war from the Allies of World War II[44] (although many more Allied POWs were victims of Unit 731 at other sites). Prisoners of war were subjected to vivisection without anesthesia, after infected with various diseases.[45] Prisoners were injected with inoculations of disease, disguised as vaccinations, to study their effects. Unit 731 and its affiliated units (Unit 1644 and Unit 100 among others) were involved in research, development, and experimental deployment of epidemic-creating biowarfare weapons in assaults against the Chinese populace (both civilian and military) throughout World War II. Human targets were also used to test grenades positioned at various distances and in different positions. Flame throwers were tested on humans. Humans were tied to stakes and used as targets to test germ-releasing bombs, chemical weapons, and explosive bombs.[46][47] Twelve Unit 731 members were found guilty in the Khabarovsk War Crime Trials but later repatriated; others received secret immunity by the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers Douglas MacArthur before the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal in exchange for biological warfare work in the Cold War for the American Force.[48]

Chinese revolutionaries including Zhao Shangzhi, Yang Jingyu, Li Zhaolin, Zhao Yiman continued to struggle against the Japanese in Harbin and its administrative area, commanding the main anti-Japanese guerrilla army-Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army which was originally organized by the Manchurian branch of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The army was supported by the Comintern after the CPC Manchurian Provincial Committee was dissolved in 1936.

Under the Manchukuo régime and Japanese occupation, Harbin Russians had a difficult time. In 1935, the Soviet Union sold the Chinese Eastern Railway (KVZhD) to the Japanese, and many Russian emigres left Harbin (48133 of them were arrested during the Soviet Great Purge between 1936 and 1938 as "Japanese spies"[49]).[29] Most departing Russians returned to the Soviet Union, but a substantial number moved south to Shanghai or emigrated to the United States and Australia. By the end of the 1930s, the Russian population of Harbin had dropped to around 30,000.[50]

Many of Harbin's Jews (13,000 in 1929) fled after the Japanese occupation as the Japanese associated closely with militant anti-Soviet Russian Fascists, whose ideology of anti-Bolshevism and nationalism was laced with virulent anti-Semitism.[51] Most left for Shanghai, Tianjin, and the British Mandate of Palestine.[52] In the late 1930s, some German Jews fleeing the Nazis moved to Harbin. Japanese officials later facilitated Jewish emigration to several cities in western Japan, notably Kobe, which came to have Japan's largest synagogue.

Post World War II

The Soviet Army took the city on 20 August 1945[53] and Harbin never came under the control of the Kuomintang, whose troops stopped 60 km (37 mi) short of the city.[54] The city's administration was transferred by the departing Soviet Army to the Chinese People's Liberation Army in April 1946. On April 28, 1946, the Communist Government of Harbin was established, making the 700,000-citizen-city the first large city under Chinese Communist force rule.[22] During the short occupation of Harbin by the Soviet Army (August 1945 to April 1946), thousands of Russian emigres who have been identified as members of the Russian Fascist Party and fled communism after the Russian October Revolution,[31] were forcibly deported to the Soviet Union. After 1952 the Soviet Union launched a second wave of immigration back to Russia.[31] By 1964, the Russian population in Harbin had been reduced to 450.[50] The rest of the European community (Russians, Germans, Poles, Greeks, etc.) emigrated during the years 1950–54 to Australia, Brazil, Canada, Israel and the USA, or were repatriated to their home countries.[31] By 1988 the original Russian community numbered just thirty, all of them elderly. Modern Russian living in Harbin mostly moved there in the 1990s and 2000s, and have no relation to the first wave of emigration.

Harbin was among one of the key construction cities of China during the First Five-Year Plan period from 1951 to 1956. 13 of the 156 key construction projects were aid-constructed by the Soviet Union in Harbin. This project made Harbin an important industrial base of China. During the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1961, Harbin experienced a very tortuous development course as several Sino-Soviet contracts were cancelled by the Soviet Union.[55] During the Cultural Revolution many foreign and Christian things were uprooted, such as the St. Nicholas church which was destroyed by Red Guards in 1966. As the normal economic and social order was seriously disrupted, Harbin's economy also suffered from serious setbacks. One of the main reasons of this setback is with its Soviet ties deteriorating and the Vietnam War escalating, China became concerned of a possible nuclear attack. Mao Zedong ordered an evacuation of military and other key state enterprises away from the northeastern frontier, with Harbin being the core zone of this region, bordering the Soviet Union. During this Third Front Development Era of China, several major factories of Harbin were relocated to Southwestern Provinces including Gansu, Sichuan, Hunan and Guizhou, where they would be strategically secure in the event of a possible war. Some major universities of China were also moved out of Harbin, including Harbin Military Academy of Engineering (predecessor of Changsha's National University of Defense Technology) and Harbin Institute of Technology (Moved to Chongqing in 1969 and relocated to Harbin in 1973).[56]

National economy and social service have obtained significant achievements since the Chinese economic reform first introduced in 1979. Harbin holds the China Harbin International economic and Trade Fair each year since 1990.[22] Harbin once housed one of the largest Jewish communities in the Far East before World War II. It reached its peak in the mid-1920s when 25,000 European Jews lived in the city. Among them were the parents of Ehud Olmert, the former Prime Minister of Israel. In 2004, Olmert came to Harbin with an Israeli trade delegation to visit the grave of his grandfather in Huang Shan Jewish Cemetery,[57] which had over 500 Jewish graves identified.[31]

On 5 October 1984, Harbin was designated a sub-provincial city by the Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee. The eight counties of Harbin originally formed part of Songhuajiang Prefecture whose seat was practically located inside the urban area of Harbin since 1972. The prefecture was officially merged into Harbin city on 11 August 1996, increasing Harbin's total population to 9.47 million.[58]

Harbin hosted the third Asian Winter Games in 1996.[59] In 2009, Harbin held the XXIV Winter Universiade.

A memorial hall honoring Korean nationalist and independence activist[60] Ahn Jung-geun was unveiled at Harbin Railway Station on 19 January 2014.[61] Ahn assassinated four-time Prime Minister of Japan and former Resident-General of Korea Itō Hirobumi at No.1 platform of Harbin Railway Station on October 26, 1909, as Korea on the verge of annexation by Japan after the signing of the Eulsa Treaty.[62] South Korean President Park Geun-Hye raised an idea of erecting a monument for Ahn while meetting with Chinese President Xi Jinping during a visit to China in June 2013.[63] After that China began to build a memorial hall honoring Ahn at Harbin Railway Station. As the hall was unveiled on 19 January 2014, the Japanese side soon lodged protest with China over the construction of Ahn's memorial hall.[64]

Geography

[[File:Harbin, China, and vicinities, near natural colors, LandSat-5, 2010-09-22.jpg|thumb|left|Harbin and vicinities, LandSat-5 satellite image, 2010-09-22]]

| Harbin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Harbin, with a total land area of 53,068 km2 (20,490 sq mi), is located in southern Heilongjiang province and is the provincial capital. The prefecture is also located at the southeastern edge of the Songnen Plain, a major part of China's Northeastern Plain.[66] The city center also sits on the southern bank of the middle Songhua River. Harbin received its nickname The pearl on the swan's neck, since the shape of Heilongjiang resembles a swan.[67] Its administrative area is rather large with latitude spanning 44° 04′−46° 40′ N, and longitude 125° 42′−130° 10' E.[68] Neighbouring prefecture-level cities are Yichun to the north, Jiamusi and Qitaihe to the northeast, Mudanjiang to the southeast, Daqing to the west, and Suihua to the northwest. On its southwestern boundary is Jilin province. The main terrain of the city is generally flat and low-lyling, with an average elevation of around 150 metres (490 ft). However, the territory that comprises the 10 county-level divisions in the eastern part of the municipality consists of mountains and uplands. The easternmost part of Harbin prefecture also has extensive wetlands, mainly in Yilan County which is located at the southwestern edge of the Sanjiang Plain.[69]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Harbin features a monsoon-influenced, humid continental climate (Dwa). Due to the Siberian high and its location above 45 degrees north latitude, the city is known for its coldest weather and longest winter among major Chinese cities.[67] Its nickname Ice City is well-earned, as winters here are dry and freezing cold, with a 24-hour average in January of only −18.4 °C (−1.1 °F), although the city sees little precipitation during the winter and is often sunny. Spring and autumn constitute brief transition periods with variable wind directions. Summers can be hot, with a July mean temperature of 23.0 °C (73.4 °F). Summer is also when most of the year's rainfall occurs, and more than half of the annual precipitation, at 524 millimetres (20.6 in), occurs in July and August alone. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 52 percent in December to 63 percent in March, the city receives 2,571 hours of bright sunshine annually; on average precipitation falls 104 days out of the year. The annual mean temperature is +4.25 °C (39.6 °F), and extreme temperatures have ranged from −42.6 °C (−45 °F) to 39.2 °C (103 °F).[70]

| Climate data for Harbin (normals 1971–2000, extremes 1961–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

34.6 (94.3) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.5 (97.7) |

35.6 (96.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

17.2 (63) |

8.5 (47.3) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −12.5 (9.5) |

−7.2 (19) |

2.3 (36.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

26.1 (79) |

27.9 (82.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

20.7 (69.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

10.07 (50.12) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −18.3 (−0.9) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.1 (70) |

14.5 (58.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−14.8 (5.4) |

4.25 (39.67) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −24.1 (−11.4) |

−19.8 (−3.6) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

0.4 (32.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

8.7 (47.7) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−19.8 (−3.6) |

−1.45 (29.39) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −38.1 (−36.6) |

−33.7 (−28.7) |

−28.4 (−19.1) |

−12.8 (9) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

4.6 (40.3) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−26.5 (−15.7) |

−35.7 (−32.3) |

−42.6 (−44.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 3.4 (0.134) |

5.3 (0.209) |

9.7 (0.382) |

18.4 (0.724) |

40.4 (1.591) |

84.4 (3.323) |

142.7 (5.618) |

121.2 (4.772) |

57.6 (2.268) |

25.9 (1.02) |

9.6 (0.378) |

5.8 (0.228) |

524.4 (20.647) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 10.3 | 13.5 | 14.2 | 12.3 | 9.9 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 7.2 | 104.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 69 | 56 | 49 | 51 | 65 | 77 | 78 | 70 | 63 | 65 | 71 | 65.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 155.9 | 179.9 | 230.9 | 231.4 | 264.1 | 260.2 | 254.2 | 247.2 | 230.5 | 206.8 | 170.2 | 139.9 | 2,571.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 56 | 62 | 63 | 57 | 58 | 56 | 54 | 57 | 61 | 61 | 60 | 52 | 58.1 |

| Source #1: China Meteorological Administration[65] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weather China[71] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

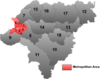

The sub-provincial city of Harbin has direct jurisdiction over 9 districts, 2 county-level cities and 7 Counties.

List of County-level divisions

| Map | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Population (2010) |

Area (km²) | Density (/km²) | ||||

| City proper | |||||||||

| Daoli District | 道里区 | Dàolǐ Qū | 923,762 | 479 | 1,929 | ||||

| Nangang District | 南岗区 | Nángǎng Qū | 1,343,857 | 183 | 7,343 | ||||

| Daowai District | 道外区 | Dàowài Qū | 906,421 | 257 | 3,527 | ||||

| Xiangfang District | 香坊区 | Xiāngfáng Qū | 916,408 | 340 | 2,695 | ||||

| Pingfang District | 平房区 | Píngfáng Qū | 190,253 | 94 | 2,024 | ||||

| Songbei District | 松北区 | Sōngběi Qū | 236,848 | 736 | 322 | ||||

| Suburb | |||||||||

| Hulan District | 呼兰区 | Hūlán Qū | 764,534 | 2,186 | 350 | ||||

| Acheng District | 阿城区 | Àchéng Qū | 596,856 | 2,770 | 215 | ||||

| Shuangcheng | 双城区 | Shuāngchéng Qū | 825,634 | 3,112 | 265 | ||||

| Satellite cities | |||||||||

| Shangzhi | 尚志市 | Shàngzhì Shì | 585,386 | 8,895 | 66 | ||||

| Wuchang | 五常市 | Wǔcháng Shì | 881,224 | 7,512 | 117 | ||||

| Rural | |||||||||

| Yilan County | 依兰县 | Yīlán Xiàn | 388,319 | 4,672 | 83 | ||||

| Fangzheng County | 方正县 | Fāngzhèng Xiàn | 203,853 | 2,993 | 68 | ||||

| Bin County | 宾县 | Bīn Xiàn | 551,271 | 3,846 | 143 | ||||

| Bayan County | 巴彦县 | Bāyàn Xiàn | 590,555 | 3,138 | 188 | ||||

| Mulan County | 木兰县 | Mùlán Xiàn | 277,685 | 3,602 | 77 | ||||

| Tonghe County | 通河县 | Tōnghé Xiàn | 210,650 | 5,755 | 37 | ||||

| Yanshou County | 延寿县 | Yánshòu Xiàn | 242,455 | 3,226 | 75 | ||||

Economy

Harbin has the largest economy in Heilongjiang province.[8] In 2013, Harbin's GDP totaled RMB501.08 billion, an increase of 8.9 percent over the previous year.[72] The proportion of the three industries to the aggregate of GDP was 11.1:36.1:52.8 in 2012. The total value for imports and exports by the end of 2012 was USD 5,330 million.[8] In 2012, the working population reached 3.147 million.

The chernozem soil in Harbin, called "black earth" is one of the most nutrient rich in all of China, making it valuable for cultivating food and textile-related crops. As a result, Harbin is China's base for the production of commodity grain and an ideal location for setting up agricultural businesses. Harbin also has industries such as light industry, textile, medicine, food, automobile, metallurgy, electronics, building materials, and chemicals which help to form a fairly comprehensive industrial system. Harbin Electric Company Limited and Northeast Light Alloy Processing Factory are two key enterprises. Power manufacturing is also a main industry in Harbin; hydro and thermal power equipment manufactured here makes up one-third of the total installed capacity in China.[73] Harbin Pharmaceutical Group, which mainly focus on research, development, manufacture and sale of pharmaceutical products, is China's second-biggest drug maker by market value.[74]

Foreign investors seem upbeat about the city. A large-scale national level international fair, Harbin International Trade and Economic Fair, has been held annually since its first session in 1990.[75] This investment and trade fair cumulatively attracting more than 1.9 million exhibitors and visitors from more than 80 countries and regions to attend in, resulting over US$100 billion contract volume concluded according to the statistics of 2013.[76] Harbin is among major destinations of FDI in Northeast China,[8] with utilized FDI totaling US$980 million in 2013.[72] After the 18th regular meeting between Sino-Russian Prime Ministers between Li Keqiang and Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev in October 2013,[77] two sides come to make an agreement that the Harbin International Trade and Economic Fair will be renamed "China-Russia EXPO" and be co-sponsored by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, Heilongjiang Provincial government, the Russian Ministry of Economic Development and Russia's Ministry of Trade and Industry.[78]

In the financial sector, Longjiang Bank and Harbin Bank are some of the largest banks in Northeast China, with headquarters in Harbin. The latter ranks 4th by competitiveness among Chinese city commercial banks in 2011.[79]

Economic Development Zones and Ports

- Harbin Economic & Technology Development Zone (National), mainly focus on telecommunications equipment, chemicals production and processing, automobile production/assembly, electronics, textiles, medical equipment and supplies.[8][80]

- Harbin High and New Technological Development Zone, focus on optical-mechanical-electrical integration, biology, medicine, electronics and information technology.[8]

- Harbin Pingfang Automobile Industrial Zone (Provincial), mainly focus on automobile production/assembly, electronics assembly & manufacturing, heavy industry, instruments & industrial equipment production.[81]

- Harbin Limin Economic Development Zone (Provincial), mainly focus on trading and distribution, food/beverage processing, medical equipment and supplies, shipping/warehousing/logistics.[82]

- Harbin Port

- Harbin Songbei Economic Development Zone

Songbei Economic Development Zone is located in Songbei District of Harbin. The zone has a planned area of 5.53 square kilometers. Electronics assembly & manufacturing, food and beverage processing are the encouraged industries in the zone.[83] Many regional and provincial headquarters of large enterprises such as the China Datang Corporation, China Netcom and China Telecom have joined in this district, preliminary constituting the economy concentration zone of the local headquarters. Regional Scientific research centers including Harbin Science and Technology Innovation Center and Harbin International Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Center are also located in this development zone. Profit from these major research institutes, Harbin ranked 9th among 50 major Chinese cities in scientific and technological innovation ability in scientific and technological competitiveness ranking in 2006, as well as ranking 6th among Chinese cities in the amount of scientific and technological achievements.[84]

- Harbin Economic and Technological Development Zone

Harbin Economic and Technological Development Zone(HETDZ) is one of the 90 national economical development zones of China. It was set up in June, 1991 and was approved by the State Council as a national development zone in April, 1993. In December 2012, Harbin High Technology Development Zone was merged into HETDZ. In 2009, the hi-tech zone was separated from HETDZ again.[85] The area now has a total area of 18.5 square-kilometers in the centralized parks, subdivided into Nangang and Haping Road Centralized Parks. The 12.2 square-kilometers Yingbin Road Hi-tech Centralized Park, which was formerly part of HETDZ, is currently under the administration of Harbin High and New Technology Industry Development Zone since 2009.

- Nangang Centralized Park: Designated for the incubation of high-tech projects and research and development base of enterprises as well as tertiary industries such as finance, insurance, services, catering, tourism, culture, recreation and entertainment, where the headquarters of large famous companies and their branches in Harbin are located.

- Yingbin Road Centralized Park: mainly focus on high-tech incubation projects, high-tech industrial development.

- Haping Road Centralized Park: Designated for a comprehensive industrial basis for the investment projects of automobile and automobile parts manufacturing, medicines, foodstuffs, electronics, textile; Automobile production and assembly raw material processing are the encouraged industries in this region.

- Harbin High and New Technology Industry Development Zone

Harbin High and New Technology Industry Development Zone is one of the 56 national High and New Technology Industry Development Zones of China.[86] The zone was first set up as a provincial level development zone in 1988, and was approved by the State Council as a national development zone in 1991 respectively.[87] It has 23.9 square-kilometers of built-area totally, and subdivided into two parts: Science and Technology Innovation Town and High-tech Industrial Development Zone.[86]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1934 | 500,526 | — |

| 1944 | 711,818 | +42.2% |

| 1953 | 1,162,962 | +63.4% |

| 1964 | 1,962,000 | +68.7% |

| 1982 | 2,542,832 | +29.6% |

| 1990 | 4,219,516 | +65.9% |

| 2000 | 9,413,359 | +123.1% |

| 2010 | 10,635,971 | +13.0% |

| Population size may be affected by changes on administrative divisions. | ||

The 2010 census revealed that the official total population in Harbin was 10,635,971, representing a 12.99 percent increase over the last decade.[88] The built-up (or metro) area, made up of all urban districts but Acheng and Shuangcheng not urbanized yet, had a population of 5,282,083 people.[89] The demographic profile for the Harbin metropolitan area in general is relatively old: 10.95 percent are under the age of 14, while 8.04 percent are over 65, compared to the national average of 16.6% and 8.87 percent, respectively. Harbin has a higher percentage of males (50.85 percent) than females (49.15 percent).[90] Harbin currently has a lower birth rate than other parts of China, with 6.95 births per 1,000 inhabitants, compared to the Chinese average of 12.13 births.[91]

Ethnic groups

Most of Harbin's residents belong to the Han Chinese majority (93.45 percent). Ethnic minorities include the Manchu, Hui, and Mongol. In 2000, 616,749 residents belonged to minority nationalities, among which the vast majority (433,340) were Manchu, contributing 70.26 percent to the minority population. The second and third largest minority groups were Koreans (119,883) and Hui nationalities (39,995).

| Ethnic groups in Harbin, 2000 census[92] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

| Han | 8,796,610 | 93.45% |

| Manchu | 433,340 | 4.6% |

| Koreans | 119,883 | 1.27% |

| Hui | 39,995 | 0.43% |

| Mongols | 13,163 | 0.14% |

| Xibe | 4,741 | 0.05% |

| Daur | 938 | 0.01% |

| Others | 4,689 | 0.05% |

Culture

The Harbin local culture is based on Han culture, combined with Manchu culture and Russian culture.[8] This combination of cultures influences the local architecture style, food, music, and customs. The city of Harbin was appointed a UNESCO City of Music on 22 June 2010 as part of the Creative Cities Network.[14]

Cuisine

Harbin is renowned for its culinary tradition. Cuisine of Harbin consist of European flavor dishes and Chinese Northern flavor dishes mainly typified by heavy sauce and deep-frying.[93]

One of the most famous dishes in Northeastern Chinese cuisine is Guo Bao Rou, a form of sweet and sour pork. It is a classic dish from Harbin which originated in the early 20th century in Daotai Fu (pinyin: Dàotái Fǔ).[94] It consists of a bite-sized pieces of pork in a potato starch batter, deep-fried until crispy. They are then lightly coated in a variation of a sweet and sour sauce, made from freshly prepared syrup, rice vinegar, sugar, flavoured with ginger, cilantro, sliced carrot and garlic. The Harbin Guobaorou is distinct from that of other areas of China, such as Liaoning, where the sauce may be made using either tomato ketchup or orange juice. Rather the Harbin style is dominated by the honey and ginger flavours and has a clear or honey yellow colour. Originally the taste was fresh and salty. In order to fete foreign guests, Zheng Xingwen, the chef of Daotai Fu, altered the dish into a sweet and sour taste. Usually, people prefer to go to several small or middle size restaurants to enjoy this dish, because it is difficult to handle the frying process at home.[94]

Demoli Stewed Live Fish is one among other notable dishes in Harbin, which is originated in a village named Demoli on the expressway from Harbin to Jiamusi. The village is now Demoli Service Area on Harbin-Tongjiang Expressway.[95] Stewed Chicken with Mushrooms, Braised Pork with Vermicelli, and quick-boil pork with Chinese sauerkraut are also typical authentic local dishes.

Since Russia had a strong influence of Harbin's history, local cuisine of Harbin also contains Russian-style dishes and flavor.[8] There are several authentic Russian-style restaurants in Harbin, especially alongside the Zhongyang Street.[96]

A popular regional specialty is Harbin-style smoked savory red sausage.[93] This product similar to Lithuanian and German sausages which are very mild, and they tend to be much more of European flavours than other Chinese sausages. In 1900, Russian merchant Ivan Yakovlevich Churin founded a branch in Harbin, which was named Churin Foreign trading company (Chinese pinyin: Qiulin Yanghang; Russian: Цюлинь Янхан) selling imported clothes, leather boots, canned foods, vodka, etc., and began to expand sales network in other cities in Manchuria.[97][98] The influx of Europeans through Trans-Siberian Railway and Chinese Eastern Railway, increased demand of European flavor food. In 1909, Churin's Sausage Factory was founded, and first produced European flavor sausage with the manufacturing process of Lithuanian staff. Since then European style sausage become a specialty of the city.[93]

A Russian style large round bread Dalieba, derived from the Russian word khleb for "bread" is also produced in Harbin's bakeries. Dalieba is a miche like sourdough bread. First introduced to the locals by a Russian baker, it has been sold in bakeries in Harbin for over a hundred years.[99] Dalieba's sour and chewy taste is different from other traditional soft and fluffy Asian style breads in other parts of China.

Kvass, a Russia-originated fermented beverage made from black or regular rye bread,[100] is also popular in Harbin.[101] Madier (derived from "Modern") ice-cream provided in the Zhongyang Street is also well known in northern China. This ice cream is made from a specific traditional recipe and it tastes a little salty but more sweet and milky. Besides its headquarters in Harbin, it also has branches in other major Chinese cities including Beijing, Shanghai, etc.[102]

Winter culture

Located in northern Northeast China, Harbin is the northernmost among major cities in China. Under the direct influence of the Siberian Anticyclone, the average daily temperature is −19.7 °C (−3.5 °F) in winter. Annual low temperatures below −35.0 °C (−31.0 °F) are not uncommon. Nicknamed "Ice City" due to its freezing cold winter, Harbin is decorated by various styles of Ice and snow Sculptures from December to March every year.[11]

The annual Harbin International Ice and Snow Sculpture Festival has been held since 1985. Although the official start date is January 5 each year, in practice, many of the sculptures can be seen before. While there are ice sculptures throughout the city, there are two main exhibition areas: enormous snow sculptures at Sun Island (Taiyang Dao, a AAAAA-rated recreational area on the opposite side of the Songhua River from the city) and the separate "Ice and Snow World" that operates each night with lights switched on, illuminating the sculptures from both inside and outside. Ice and Snow World features illuminated full-size buildings made from blocks of 2–3 feet thick crystal clear ice directly taken from the Songhua River which passes through the city. The sculptures inside the exhibition ground takes 15,000 workers to work for 16 days. In early December, ice artisans cut 120,000 cubic metres (4.2 million cubic feet) of ice blocks from Songhua river's frozen surface as raw materials for the ice sculptures' show.[103] Massive ice buildings, large-scale snow sculptures, ice slides, festival food and drinks can also be found in several parks and major avenues in the city. Winter activities in the festival include Yabuli Alpine Skiing, snow mobile driving, winter-swimming in Songhua River, and the traditional ice-lantern exhibition in Zhaolin Garden, which was first held in 1963.[104] Snow carving and ice and snow recreations are famous nationwide, especially among Asian countries including Korea, Japan, Thailand and Singapore.[103]

The "Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival" is one of the four largest ice and snow festivals in the world, along with Japan's Sapporo Snow Festival, Canada's Quebec City Winter Carnival, and Norway's Holmenkollen Ski Festival.[8]

Every November, the city of Harbin sends teams of ice artisans to the United States to promote their unique art form. It takes more than 100 artisans to create ICE!, the annual display of indoor Christmas-themed ice carvings in National Harbor, Maryland; Nashville, Tennessee; Kissimmee, Florida; and Grapevine, Texas.

The Music City

Founded in 1908, the Harbin Symphony Orchestra was China's oldest symphony orchestra. Harbin No.1 Music School was also the first music school in China, which was founded in 1928. Nearly 100 famous musicians have studied at the school since its founding, said Liu Yantao, deputy chief of Harbin Cultural, Press and Publication Bureau. Every year, there are thousands of youngsters start their music dreams in this city, and the "Haerbin Summer Music Concert" serial activities that always be held in the every year's summer present the music passion of the locals.

UNESCO recognizes China's Harbin as "The Music City" as part of the Creative Cities Network in 2010.[14]

Harbin Summer Music Concert

Harbin Summer Music Concert ('Concert' for short) is a national concert festival, which is held on August 6 every two years for a period of 10~11 days. During the concert, multiple evenings, concert, race and activities are held. The artists come from all over the world.

The 'Harbin Summer Music Month', which was then renamed as 'Harbin Summer Music Concert', was held in August 1958. The first formal Concert was held on August 5, 1961 in Harbin Youth Palace, and kept on every year until 1966 when the Cultural Revolution started in China.[105] In 1979, the Concert was recovered and from 1994, it has been held every two years. As a part of 2006 Harbin Summer Music Concert's opening ceremony, a 1,001-piano concert was held in Harbin's Flood memorial square located at the north end of Zhongyang Street (Chinese: 中央大街; pinyin: Zhōngyāng dàjiē) on August 6, 2006.[106][107] Repertoires of the ensemble consisted of Triumphal March, Military March, Radetzky March and famous traditional local song On The Sun Island、. This concert set a new Guinness World Record for largest piano ensemble, surpassing the previous record held by German artists in a 600-piano concert.[14] In 2008, the 29th Harbin Summer Music Concert was held on August 6.

Television and Radio

- Heilongjiang Television (HLJTV) serves as the media outlets of this region, broadcasts on seven channels as well as a satellite channel for other provinces.

- Harbin Television (HRBTV) serves as a municipal station, which has five channels for specialized programming.

- Long Guang, Dragon Broadcast, formerly Heilongjiang People's Broadcasting Station, the radio station group that serves the whole Heilongjiang region, providing seven channels including a Korean language broadcast station.

- Harbin People's Broadcasting Station (HPBS), broadcasts music, news, traffic, economy and life in Harbin and adjacent areas including Daqing, Suihua and Fuyu.

Printed Media

Major local newspapers include the Harbin Daily, New Metropolis Newspaper, Life Newspaper, New Evening News, Heilongjiang Morning Paper and Heilongjiang Daily.

Architecture

Harbin is notable for its combination of Chinese and European architecture styles. Many Russian and other European style buildings are protected by the government. The architecture in Harbin gives it the nicknames of "Oriental Moscow" and "Oriental Paris".[67]

_-_panoramio.jpg)

Zhongyang Street, one of the main business streets in Harbin, is a remnant of the bustling international business activities at the turn of the 20th century. First built in 1898, The 1.4 km (0.87 mi) long street is now a veritable museum of European architectural styles: Baroque and Byzantine façades,[8] little Russian bakeries and French fashion houses, as well as non European architectural styles: American eateries, and Japanese restaurants.[108]

The Russian Orthodox church, Saint Sophia Cathedral, is also located in the central district of Daoli.[8] Built in 1907 and expanded from 1923 to 1932, it was closed during the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution periods. Following its designation in 1996 as a national cultural heritage site (First class Preserved Building),[109] it was turned into a museum as a showcase of the history of Harbin city in 1997.[110] The 53.35 m (175.0 ft)-tall Church, which covers an area of 721 square meters, is a typical representative of Byzantine architecture.[111]

Many citizens believe that the Orthodox church damaged the local feng shui, so they donated money to build a Chinese monastery in 1921, the Ji Le Temple. There were more than 15 Russian Orthodox churches and two cemeteries in Harbin until 1949. The Communist Revolution, and the subsequent Cultural Revolution, and the decrease in the ethnic Russian population, saw many of them abandoned or destroyed. Today, about 10 churches remain, while services are held only in the Church of the Intercession in Harbin.[112]

Sports

As the center of winter sports in China, many famous winter sports athletes come from Harbin. Olympic medalists include short track star Wang Meng (six-time medalist), long track skater Zhang Hong (2014 Sochi, gold medal), and pairs figure skaters Shen Xue and Zhao Hongbo (2002 Salt Lake City and 2006 Torino bronze medals, and 2010 Vancouver, gold medal), Zhang Dan and Zhang Hao, (2006 Torino, silver medal) and Pang Qing and Tong Jian. (2010 Vancouver, silver medal)[113]

Harbin has an indoor speed skating arena, Heilongjiang Indoor Rink, as one of four in China.

Mutual cooperation of the Far Eastern State Academy of Physical Culture and the Harbin Institute of Physical Education started an exchange of sports and cultural delegations, holding of sports, training of Chinese students in Khabarovsk, Russia and Harbin. Russian side started to have plans to introduce bandy to China while Harbin has good preconditions to become one of the strong points of this sport in China.[114] The national team is based in Harbin,[115][116] and it was confirmed in advance that they would play in the 2015 Bandy World Championship.[117] Despite being there for the first time, the Chinese team did not finish last.

Harbin Yiteng Football Club currently play home soccer matches at Harbin International Conference Exhibition and Sports Center, a 50000-seated stadium. The team gain promotion to China's top tier for the first time when they came second within the 2013 China League One division.

Events

The 1996 Asian Winter Games were held in Harbin. The Alpine skiing events was held in Yabuli ski resort. In the frame of this campaign to assert its role on the world scene, Harbin hosted city of the 2009 Winter Universiade. Local Government spent 3.6 billion yuan for this event, with 2.63 billion used to in construction and renovation of its sport infrastructure for this Universiade.[118]

Harbin hosted the Asian Basketball Confederation Championship in 2003, in which China won the championship on their home court for the thirteenth time.

Harbin bid to host the 2010 Winter Olympics, which was ultimately awarded to Vancouver, Canada.[119]

Transport

Railway

Located at the junction of "T-style" mainline system, Harbin is an important railroad hub of the Northeast China Region.[120] Harbin Railway Bureau is the first Railway Bureau established by People's Republic of China Government, of which the railway density is the highest in China. Five conventional rail lines radiate from Harbin to: Beijing (Jingha Line), Suifenhe (Binsui Line), Manzhouli (Binzhou Line), Beian (Binbei Line) and Lalin (Labin Line). In addition, Harbin has a high-speed rail line linking Dalian, Northeast China's southernmost seaport. In 2009, construction began on the new Harbin West Railway Station with 18 platforms, located on the southwestern outskirts of the city. In December 2012, the station was opened, as China unveiled its first high-speed rail running through regions with extremely low winter temperatures. with scheduled runs from Harbin to Dalian.[121] The weather-proof CRH380B bullet trains serving the line can accommodate temperatures from minus 40 degrees Celsius to 40 degrees Celsius above zero.[122]

The city's main railway stations are the Harbin Railway Station, which was first built in 1899 and expanded in 1989; the Harbin East Railway Station, which opened in 1934; and the Harbin West Railway Station, which was built into the city's high-speed railway station in 2012.[120] Another main station under construction, Harbin North Railway Station, will be open for public service in 2015, along with new built Harbin-Qiqihar Passenger Railway.[123]

Direct passenger train service is available from Harbin Railway Station to large cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guangzhou, Jinan, Nanjing and many other major cities in China.[73] Direct High-speed railway service began operation between Harbin West and Shanghai Hongqiao stations since December 28, 2013, shorten the journey time to 12 hours.[124]

- Harbin railway system

-

Harbin Railway Station

-

Harbin West Railway Station

Road

As an important regional hub in Northeast China, Harbin has an advanced highway system. Major highways which pass through or terminate in Harbin include the Beijing–Harbin, Heihe–Dalian, Harbin–Tongjiang, Changchun–Harbin, and Manzhouli–Suifenhe highways.

- G1 Beijing–Harbin Expressway

- G10 Suifenhe–Manzhouli Expressway

- G1011 Harbin–Tongjiang Expressway, a spur of G10 that extends west to Tongjiang, formerly part of China National Highway 010

- G1111 Hegang–Harbin Expressway, a spur of G11 Hegang–Dalian Expressway

- G1211 Jilin–Heihe Expressway, a spur of G12 Hunchun–Ulanhot Expressway that extends north to Heihe

- China National Highway 102

- China National Highway 202

- China National Highway 221

- China National Highway 222

- China National Highway 301

Air

Harbin Taiping International Airport, which is 35 kilometres (22 miles) away from the urban area of Harbin, is the second largest international airport in Northeast China. The technical level of flight district is 4E, which allows all kinds of large and medium civil aircraft. There are flights to over thirty large cities including Beijing, Tianjing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Qingdao, Wenzhou, Xiamen, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Shenyang, Dalian, Xi'an and Hong Kong.[73] In addition there are also scheduled international flights between Harbin and Russia, Singapore, Malaysia, and South Korea. In June 2015, The first LCC international air routes to Japan, Destination is City of Nagoya is was to be beginning.[120] Because of the freight capability limitation, construction of the T2 Terminal began on October 31, 2014. The 160,000-square-meter T2 Terminal is scheduled to be finished in 2017, and will increase the freight capacity of the airport to three times of the previous.[125]

Subway

Construction of Harbin Subway started on 5 December 2006. The total investment for the first phase is RMB5.89 billion. Twenty stations were planned to be set on this 17.73 km (11.02 mi) long line starting from Harbin East Railway Station to the 2nd Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University in the west of the city. A subway depot, a command center and two transformer substations will be built along the line. Most of the subway's route follows the air defence evacuation tunnel left from the "7381" Project which started in 1973 and ended in 1979. The 7381 project was intended to protect Harbin from the former Soviet Union's possible invasion or nuclear attack.

The Line 1 of Harbin Metro actually opened on 26 September 2013.[126] It is oriented along the east–west axis of the urban area of Harbin: from north-east (Harbin East Railway Station) to south-west (2nd Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University).[127] Line 2 and Line 3 are under construction. Line 2 runs from Songbei District to Xiangfang District and Line 3 runs next to 2nd ring road of Harbin. In the long term, the city plans to build nine radiating subway lines and a circle line in downtown and some suburban districts, which account for 340 km (211.3 mi) by 2025.[128]

Picture References:

Ports and waterways

There are more than 1,900 rivers in Heilongjiang, including the Songhua River, Heilong River and Wusuli River, creating a convenient system of waterway transportation. Harbin harbor is one of eight inland ports in China and the largest of its type in Northeast China. Available from mid-April until the beginning of November, passenger ships sail from Harbin up the Songhua River to Qiqihar, or downstream to Jiamusi, Tongjiang, and Khabarovsk in Russia.[73]

Education

As Harbin serves as an important military industrial base after PRC's foundation, it is home to several key universities mainly focus on the science and technology service of national military and aerospace industry.[129] Soviet experts played an important role in many education projects in this period. However, due to the threat of possible war with the Soviet Union, several colleges were moved southwards to Changsha, Chongqing, and several other southern cities in China in the 1960s. Some of these colleges were returned to Harbin in the 1970s.

Among these universities the best-known is Harbin Institute of Technology, one of China's better known universities. Founded in 1920, the university has developed into an important research university mainly focusing on engineering (e.g. in space science and defense-related technologies),[130][131] with supporting faculties in the sciences, management, humanities and social sciences. The institute's faculty and students contributed to and invented China's first analog computer, the first intelligent chess computer, and the first arc-welding robot. In 2010, research funding from the government, industry, and business sectors surpassed RMB1.13 billion, the second highest of any university in China.[73]

- Harbin Institute of Technology

- Harbin Engineering University (former department of Shipbuilding Engineering of Harbin Military Academy of Engineering)

- Northeast Agricultural University*Northeast Forestry University

- Heilongjiang University

- Harbin Jewish Research Center

- Harbin Medical University

- Harbin Normal University

- Harbin University of Science and Technology

- Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine

- Heilongjiang Institute of Technology

- Heilongjiang East College

- Harbin Advance Technical College

- Harbin University of Commerce

- The Harbin Mandarin School, Harbin also offers private one-to-one intensive Mandarin Chinese courses.

International relations

Harbin has town twinning and similar arrangements with approximately 30 places around the world, as well as some other cities within China. For a list, see List of twin towns and sister cities in China → H.

In 2009 Harbin opened an International Sister Cities museum. It has 1,048 exhibits in 28 rooms, with a total area of 1,800 square metres (19,375 square feet).[132]

On September 3, 2015, China and Russia signed an agreement to re-open the Russian consulate in Harbin, as the former Soviet consulate was closed in 1962 after Sino-Soviet split. China will also establish a corresponding consulate in Vladivostok.[133]

See also

- Harbin Ferris Wheel

- List of cities in the People's Republic of China by population

- List of current and former capitals of subnational entities of China

- 2013 Harbin smog

Notes

- ↑ "Administrative Divisions". Harbin Municipal Government. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ "Leader Information" (in Chinese). harbin.gov.cn. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

- ↑ "Survey of the City". Basic Facts. Harbin Municipal Government. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- 1 2 "2010年哈尔滨市第六次全国人口普查主要数据公报(Sixth National Population Census of the People's Republic of China" (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of China. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- ↑ "Illuminating China's Provinces, Municipalities and Autonomous Regions-Heilongjiang". PRC Central Government Official Website. 2001. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ 中央机构编制委员会印发《关于副省级市若干问题的意见》的通知. 中编发[1995]5号 (in Chinese). 豆丁网. 1995-02-19. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

- ↑ 最新中国城市人口数量排名(根据2010年第六次人口普查) (in Chinese). www.elivecity.cn. 2012. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Harbin (Heilongjiang) City Information". hktdc.com. 28 Jan 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Polish Studies in China". The Warsaw Voice. April 30, 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Jianwei, Wabng (2014-02-01). "People enjoy ice sculptures in Harbin". English.news.cn. Xinhua. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Chinese ice sculptures melting". BBC. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ 王欣欣 (December 25, 2013). 哈爾濱打造對俄開放中心城市 (in Chinese). Hong Kong: 香港文匯報. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- ↑ "China information-Harbin section". http://www.kzzi.com/. Retrieved 15 October 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 3 4 王寒露 (June 26, 2010). "UN recognizes China's northeastern Harbin as "Music City"" (Xinhua). People's Daily Online. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ 苏金源 (February 1982). 论完颜阿骨打的政治、经济改革 (in Chinese). 《史学集刊》.

- 1 2 "The Remains of Huining in Shangjing of Jin Dynasty". China Kindness Tour. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- ↑ Tao (1976). Pages 28-32.

- 1 2 Tao, p.44

- ↑ "A-ch'eng". (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 4, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- 1 2 金上京历史博物馆 (Jin Dynasty Shangjing History Museum) (Chinese)

- ↑ "阿骨打、粘罕雕像落成 Aguda's and Nianhan's statues completed" (in Chinese). 东北网. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Historical Evolution". Harbin Municipal Government. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ 哈尔滨市地方志编纂委员会 (1998). 哈尔滨市志 History of Harbin (in Chinese). 黑龙江人民出版社. ISBN 978-7-207-03841-8.

- ↑ Jing-tao, Wang. "Analysis of the Rat Plague of Northeast China and the Sanitary and Antiepidemic Condition of Yanbian in the Early 20th Century" (in Chinese). Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Gamsa, M. (1 February 2006). "The Epidemic of Pneumonic Plague in Manchuria 1910-1911". Past & Present 190: 147–183. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtj001.

- ↑ Article in Chinese. "130th memorial of Dr. Wu Lien-teh". Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sinoforum – Harbin" (in Polish). Sinoforum.pl. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ Bakich, Olga Mikhailovna, "Emigre Identity: The Case of Harbin," The South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol.99, No.1 (2000): 51–73.

- 1 2 3 Эхо планеты № 42. (Echo of the Planet No.42) (in Russian). ИТАР-ТАСС (Russian News Agency "TASS"). p. 30.

- ↑ “Harbintsy” is the Russian word for “people of Harbin”, cf. Berliners, New Yorkers, Muscovites. It applies to any nationality, not just Russians. While the paper focuses on Russian Harbintsy, many of their experiences were shared by Russians living elsewhere in “Russian Manchuria”.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Harbin Connection: Russians from China" (PDF). from Shen Yuanfang and Penny Edwards (eds) Beyond China: Migrating Identities, Centre for the Study of the Southern Chinese Diaspora, Australian National University, Canberra, 2002, pp7587. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Patrick Fuliang Shan, “‘A Proud and Creative Jewish Community:’ The Harbin Diaspora, Jewish Memory and Sino-Israeli Relations,” American Review of China Studies, Fall 2008, pp.15-29.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Diasporas. Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Vol. I, Jewish Diaspora in China by Xu Xin, p.159, Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (Eds.), Springer 2004, ISBN 0-306-48321-1

- ↑ Collective security

- ↑ Matsuzaka, The Making of Japanese Manchuria, 1904–1932

- ↑ Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors, 1996, p.136

- ↑ Harris, Sheldon H. (1994). Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare 1932–45 and the American Cover-Up. California State University, Northridge: Routledge. pp. 26–33. ISBN 0-415-93214-9.

Page 26: Zhong Ma Prison Camp's creation; Page 33: Pingfang site's creation.

- ↑ David C. Rapoport. "Terrorism and Weapons of the Apocalypse". In James M. Ludes, Henry Sokolski (eds.), Twenty-First Century Weapons Proliferation: Are We Ready? Routledge, 2001. pp. 19, 29

- ↑ Khabarovsk War Crime Trials. Materials on the Trial of Former Servicemen of the Japanese Army Charged with Manufacturing and Employing Biological Weapons, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1950. p. 117

- ↑ Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors, Westviewpress, 1996, p.138

- ↑ The Imperial Japanese Medical Atrocities and Its Enduring Legacy in Japanese Research Ethics

- ↑ "旧日本軍の731部隊(細菌部隊)人体実験に朝鮮人 日本の公文書で初確認 AII The War Crime "Unit 731" and Chinese, Korean Civilian. ci". http://www1.korea-np.co.jp (in Japanese). 조선신보. Retrieved 15 October 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Seiichi Morimura, The Devil's Gluttony (Моримура Сэйити КУХНЯ ДЬЯВОЛА-ДОСТАВКА В ЖИВОМ ВИДЕ ПО ПЕРВОМУ ТРЕБОВАНИЮ)" (in Russian). 1981. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "The devil unit, Unit 731. 731部隊について" (in Japanese). Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Richard Lloyd Parry (February 25, 2007). "Dissect them alive: order not to be disobeyed". London: Times Online.

- ↑ Monchinski, Tony (2008). Critical Pedagogy and the Everyday Classroom. Volumen 3 de Explorations of Educational Purpose. Springer, p. 57. ISBN 1402084625

- ↑ Neuman, William Lawrence (2008). Understanding Research. Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, p. 65. ISBN 0205471536

- ↑ Hal Gold, Unit 731 Testimony, 2003, p. 109

- ↑ These statistics, based on research work by A. B. Roginsky and O. A. Gorlanov of Memorial’s Research and Information Centre, were provided to the author in May 2002.

- 1 2 Hal Gold, Clausen, Søren and Stig Thøgersen (eds). 1995. The Making of a Chinese City:History and Historiography in Harbin. New York: M. E. Sharpe

- ↑ Stephan, John J. 1978. The Russian Fascists: Tragedy and Farce in Exile 192545. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- ↑ Huang. "Shanghai Jews as seen by Chinese Jewish People in Shanghai for 138 years". The Scribe. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ LTC David M. Glantz, "August Storm: The Soviet 1945 Strategic Offensive in Manchuria". Leavenworth Papers No. 7, Combat Studies Institute, February 1983, Fort Leavenworth Kansas.

- ↑ "Освобождение городов КИТАЙ(Liberation of Cities-China)". www.soldat.ru (in Russian). 9 May 2000. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Chinese Government’s Official Web Portal (English). China: a country with 5,000-year-long civilization. retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "Japan-China Relations in the 21st Century". Kendairen. Japan Federation of Economic Organizations. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Harbin people congratulate Olmert on Israeli election success". People's Daily. 30 March 2006. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ 哈尔滨市历史沿革. www.xzqh.org (in Chinese). 2014-05-16. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ World of Chinese Stamps and Philatelic Items

- ↑ "What Defines a Hero?". Japan Society. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ↑ Peng, Fu (20 January 2014). "Korean patriot Ahn Jung Geun's memorial held in Harbin". Xinhuanet English. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Description of Ito, Hirobumi (1841 - 1909), Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures". National Diet Library of Japan. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Memorial hall for Korean nationalist Ahn Jung Geun opens in China". Kyodo News International. 1 January 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Japan protest over Korean assassin Ahn Jung-geun memorial in China". BBC News. 20 January 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 "China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System" (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Xiu Jun, Li (2001). "The Alkili-saline Land and Agricultural Sustainable Development of the Western Songnen Plain in China (Alkali is misspelled in the original title)". en.cnki.com. SCIENTIA GEOGRAPHICA SINICA. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Harbin ( Heilongjiang ) City Information".

- ↑ "Geographic Location". Basic Facts. Harbin Municipal Government. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ 2003. Wang A., Zhang S., and Zhang B. A study on the change of spatial pattern of wetland in the Sanjiang Plain. Acta Ecologica Sinica 23(2):237-243

- ↑ "Climatological Summary". Harbin Municipal Government. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- ↑ 哈尔滨城市介绍以及气候背景分析. 中国天气网 (in Chinese). 中国气象局公共气象服务中心. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Statistics Communique on National Economy and Social Development of Harbin, 2013" (PDF) (in Chinese). Harbin Municipal Statistics Bureau. 2014-03-18. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "China Briefing Business Guide: Harbin". China-briefing.com. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ Harbin Pharmaceutical to issue RMB 800 mln short-term bonds

- ↑ 1990年创办至今 回眸哈洽会 十四年这样走过 (in Chinese). 生活报(Life Newspaper). 2004-06-14. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ "The 24th China Harbin International Economic and Trade Fair will be held from June 15th to 19th in Harbin". Departamento Econômico e Comercial em Portugal. 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ "哈洽会"今年正式更名为"中国-俄罗斯博览会" (in Chinese). 黑龙江日报. 2014-03-21. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ 哈洽会升级中俄博览会 6月30日—7月4日举行 (in Chinese). 黑龙江新闻网-生活报. 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ 2011全国城市商行竞争力排名 哈尔滨银行居第四 (in Chinese). 哈尔滨新闻网. 2011-10-11. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ "Harbin Economic & Technology Development Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Harbin Pingfang Automobile Industrial Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Harbin Limin Economic Development Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Harbin Songbei Economic Development Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Scientific Technology and Education". Harbin Information Center. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ↑ "Survey of Harbin Economic-Technological Development Zone" (in Chinese). Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Park introduction of Harbin High and New Technology Industry Development Zone". Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ↑ "Harbin Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone | China Industrial Space". Rightsite.asia. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ 哈尔滨市2010年第六次全国人口普查主要数据公报 (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2011-12-10. Retrieved 2013-01-26.

- ↑ http://www.citypopulation.de/php/china-heilongjiang-admin.php

- ↑ 哈尔滨人口突破千万 外来人口增速超本地 (in Chinese). Dongbeiwang. 2011-05-13. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- ↑ 哈市最新常住人口1063.59万 居副省级城市第三位 (in Chinese). www.harbin.gov.cn. 11 November 2011.

- ↑ Department of Population, Social, Science and Technology Statistics of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司) and Department of Economic Development of the State Ethnic Affairs Commission of China (国家民族事务委员会经济发展司), eds. Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China (《2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料》). 2 vols. Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House (民族出版社), 2003. (ISBN 7-105-05425-5)(Chinese)

- 1 2 3 "31 dishes: A guide to China's regional specialties". CNN Travel. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- 1 2 "锅包肉"来自道台府. 生活报 (in Chinese). 黑龙江新闻网. 25 October 2005. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ↑ 哈同公路得莫利服务区打造“龙江第一服务区”(Chinese)

- ↑ "Harbin Cuisine". visitourchina. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ Торговая фирма «И. Я. Чурин и Ко» и табачная фабрика А. Лопато // Китайский информационный Интернет-центр 10/01/2003

- ↑ Спутник по Сибири, Маньчжурии, Амуру и Уссурийскому краю. 1911 год (6 год издания). Составил И. С. Кларк. VII выпуск. — Иркутск. — Паровая типо-литография П. Макушина и В. Посохина. — С. 106.

- ↑ "Recreating 大列巴 (DaLieba) - the Chinese sourdough bread with 100+ years of history and a Russian heritage". The Fresh Loaf. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ Kvass (Russian Fermented Rye Bread Drink) Recipe

- ↑ 哈尔滨特色饮料“格瓦斯”竞相亮相哈洽会(Chinese)

- ↑ 马迭尔进京布局意在全国市场. 贺陈慧 (in Chinese). 高端旅游周刊. 31 July 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Ice is money in China's coldest city". www.smh.com.au. 13 November 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Ice Lantern Exhibition". China National Tourist Office. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ↑ Introduction of Harbin Summer Music Concert

- ↑ 李威 封娇 李木双 (10 August 2006). 第28届中国·哈尔滨之夏音乐会琴宝隆之声·千台钢琴演奏会吉尼斯纪录申请过程. 新晚报 (in Chinese). 新浪娱乐. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ 王玮 (8 August 2006). "琴宝隆之声"千台钢琴演奏会奏响华彩乐章. 新浪娱乐 (in Chinese). 新浪娱乐. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ "Central Street". China National Tourist Office. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ↑ "PRESERVED BUILDINGS." Harbin Urban and Rural Planning Bureau.

- ↑ Yukiko Koga. "The Atmosphere of a Foreign Country": Harbin's Architectural Inheritance. In: Anne M. Cronin, Kevin Hetherington. Consuming the Entrepreneurial City: Image, Memory, Spectacle. Routledge, 2008. p.229.

- ↑ "St. Sofia Orthodox Church". China National Tourist Office. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ↑ The Church of the Protection of the Mother of God in Harbin (Orthodoxy in China)

- ↑ http://www.olympic.org/olympic-results

- ↑ Хоккеем с мячом заинтересовались в Харбинском институте физической культуры (in Russian). Федерация хоккея с мячом Хабаровского края. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ China team may be take part in world championship 2015

- ↑ Китай сыграет на ЧМ-2015

- ↑ National team of China none the less will come to Khabarovsk

- ↑ 第24届大冬会09年2月18举行 共设12大项82小项. www.china.com.cn (in Chinese). 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ http://gamesbids.com/eng/past-bid-results/

- 1 2 3 "Harbin Transportation". China National Tourist Office. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ↑ "Harbin-Dalian high-speed rail went into operation on December 1". Website of Jilin Province Government. 2012-11-27. Retrieved 2013-01-26.

- ↑ "China tests world's first alpine high-speed rail line". Xinhuanet. 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2013-01-26.

- ↑ 哈尔滨北站和哈齐客专明年同步使用 (in Chinese). 东北网-黑龙江晨报. 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ↑ 哈尔滨至上海高铁开通 (in Chinese). 科技日报. Retrieved 2014-05-17.

- ↑ 周琳. "哈尔滨太平机场扩建主体工程开工 T2航站楼3年内投用". 生活报 (in Chinese) (东北网). Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Metro line operational in China's Harbin" 2013-09-26

- ↑ (Chinese) 哈尔滨地铁1号线载客试运营正式开通 2013-09-26(Chinese)

- ↑ 哈尔滨市人民政府 (2011-03-09). 哈埠地铁2013年载客试运行 6月份进行铺轨工程 (in Chinese). Retrieved 2014-01-25.

- ↑ "Scientific Technology and Education". Harbin Municipal Government. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ↑ "Kuaizhou – China secretly launches new quick response rocket". Retrieved 2014-04-22.

Built by the Harbin Institute of Technology, the new satellite will be used for emergency data monitoring and imaging...

- ↑ "Work at HIT as lecturer after graduation" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ "Harbin International Sister Cities Museum". China Daily.Com. 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- ↑ "Документы, подписанные по итогам российско-китайских переговоров 3 сентября 2015 г.". http://www.russia.org.cn/ (in Russian). The Embassy of the Russian Federation in the People's Republic of China. 3 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015. External link in

|website=(help)

References

- Jing-shen, Tao (1976). The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-95514-7.

- Lahusen, Thomas (November 15, 2001). Harbin and Manchuria: Place, Space, and Identity (South Atlantic Quarterly (Book 99) ed.). Location: Duke University Press Books. pp. 276 pages. ISBN 0-295-95514-7.

- Walravens, Hartmut. "German Influence on the Press in China." – In: Newspapers in International Librarianship: Papers Presented by the Newspaper Section at IFLA General Conferences. Walter de Gruyter, January 1, 2003. ISBN 3110962799, 9783110962796.

- Also available at (Archive) the website of the Queens Library – This version does not include the footnotes visible in the Walter de Gruyter version

- Also available in Walravens, Hartmut and Edmund King. Newspapers in international librarianship: papers presented by the newspapers section at IFLA General Conferences. K.G. Saur, 2003. ISBN 3598218370, 9783598218378.

Further reading

- Meyer, Mike, "Manchuria Under Ice", Departures Magazine, Nov/Dec 2006, 292–297.

- Nikos Kavvadias, a popular Greek poet born in Harbin by Greek parents from Kefalonia, Greece

- Jan, Michel, "Cruelle est la terre des frontières", Payot, Paris, 2006 (in French).

External links

- Harbin Government website

Harbin travel guide from Wikivoyage

Harbin travel guide from Wikivoyage

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest cities or towns in China Sixth National Population Census of the People's Republic of China (2010) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Shanghai  Beijing |

1 | Shanghai | Shanghai | 20,217,700 | 11 | Foshan | Guangdong | 6,771,900 |  Chongqing  Guangzhou |

| 2 | Beijing | Beijing | 16,858,700 | 12 | Nanjing | Jiangsu | 6,238,200 | ||

| 3 | Chongqing | Chongqing | 12,389,500 | 13 | Shenyang | Liaoning | 5,718,200 | ||

| 4 | Guangzhou | Guangdong | 10,641,400 | 14 | Hangzhou | Zhejiang | 5,578,300 | ||

| 5 | Shenzhen | Guangdong | 10,358,400 | 15 | Xi'an | Shaanxi | 5,399,300 | ||

| 6 | Tianjin | Tianjin | 10,007,700 | 16 | Harbin | Heilongjiang | 5,178,000 | ||

| 7 | Wuhan | Hubei | 7,541,500 | 17 | Dalian | Liaoning | 4,222,400 | ||

| 8 | Dongguan | Guangdong | 7,271,300 | 18 | Suzhou | Jiangsu | 4,083,900 | ||

| 9 | Chengdu | Sichuan | 7,112,000 | 19 | Qingdao | Shandong | 3,990,900 | ||

| 10 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 7,055,071 | 20 | Zhengzhou | Henan | 3,677,000 | ||

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

.svg.png)