Hanau epe

The Hanau epe (also, hanau eepe: supposed to mean "Long-ears") were a semi-legendary people who are said to have lived in Easter Island, where they came into conflict with another people known as the Hanau momoko or "short-ears". A decisive battle occurred which led to the defeat and extermination of the Hanau epe. According to the legend, these events are supposed to have happened at some point between the 16th and 18th centuries, probably in the late 17th century.

The historical facts, if any, behind this story are disputed. Since the victorious "Hanau momoko" are usually assumed to be the surviving Polynesian population, there has been much speculation about the identity of the vanished Hanau epe. Various theories have been put forward, most notably Thor Heyerdahl's claim that they were ancient migrants from Peru who were the original occupants of the island and the creators of its famous stone monuments.

Heyerdahl's theories have not received much support among modern scholars, many of whom doubt whether the events described in the story ever took place. It has also been argued that the traditional designations of "long ears" and "short ears" derive from a misinterpretation of similar-sounding words meaning "stocky" and "slim" peoples.[1]

Story

There are two legends about how the Hanau epe reached Easter Island. The first is that they arrived some time after the local Polynesians and tried to enslave them. However, some earlier accounts place the Hanau epe as the original inhabitants,[2] and the Polynesians as later immigrants from Rapa Iti. Alternatively, the "epe" and "momoku" may simply have been two groups or factions within the Polynesian population. One version states that both groups originated from the original crews of the Polynesian leader Hotu Matua, who founded the settlement on Easter island.[3]

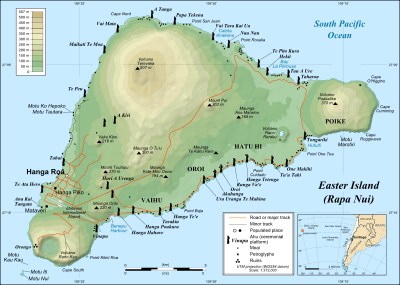

The story states that the two groups lived in harmony until a conflict arose. The source of the conflict varies in different tellings or retellings of the legend. The Hanau epe were soon overwhelmed by the Hanau momoko, and were forced to retreat, taking refuge in a corner of the island near Poike, protected by a long ditch, which they turned into a firewall. They intended to kill the Hanau momoko by burning them in the fire-ditch. The Hanau momoko found a way round the ditch, attacking the Hanau epe from behind, and pushing them into their own inferno. All but two of the Hanau epe were killed and were buried in the ditch. The two escaped to a cave, at which one was found and killed, leaving only one survivor.[3][4] The ditch was thereafter known as Ko Te Umu O Te Hanau Eepe (the Hanau Eepe's Oven).

Theories

Meaning of the names

The traditional interpretation of the names has typically been explained as a reference to the cultural practice of inserting ornaments into the earlobe to extend it, the "long eared" group either using the ornaments to signify higher class-status or ethnic difference from the unadorned "short" eared people. However scholars have increasingly taken the view that the names do not refer to ears at all. Sebastian Englert states that "Long-Ear" is a misinterpretation of Hanau ‘E‘epe, meaning "stout race". His dictionary entry for hanau includes "race, ethnic group. Hanau eepe, the thick-set race; hanau momoko, the slender race (these terms were mistranslated as "long-ears" and "short-ears")."[5] Steven R. Fischer also argues that the traditional translation is in error, and that the terms should refer to stocky or stout peoples, and slim peoples.[1]

The battle

Whether any battle took place at the Poike ditch itself is disputed. A study in 1961 dated a layer of ash from the ditch to 1676, apparently confirming the story of a fire there at around the time the battle is supposed to have taken place.[3] However, in 1993 Jo Anne Van Tilburg, writing in the journal Archaeology stated, "Excavations by the University of Chile of the so-called Poike Ditch have failed to come up with the charcoal and bone to prove that such a legendary battle actually took place."[6] It has been suggested that the ditch was in fact used to hold a series of earth ovens, or cooking pits, to prepare food for workers in a nearby quarry.[7]

Ethnic differences

Various theories have been put forward to explain the alleged ethnic difference between the two groups. Routledge in 1919 appeared to believe that the Hanau epe were a negroid population that preceded the Polynesians.[3] Thor Heyerdahl popularised the view that they were a South American indigenous people, who were pale skinned with red hair.[8] Heyerdahl's Kon-Tiki expedition was designed to show that migrants from Peru could have reached Polynesia. He believed that the Hanau epe were the earliest inhabitants of the island; they created its unique monuments, which resemble similar sculptures found in the Americas, but were eventually killed off by either the Polynesians or a later wave of migrants from the Northwest coast of America.[9]

Wilhelm and Sandoval in 1966 took the view that they came later than the followers of Hotu Matua, possibly another wave of Polynesians. Rupert Ivan Murrill, writing in 1969, argued that both groups were Polynesians.[3] Most evidence suggests that the original Easter Islanders were Polynesian in origin.[10] Steven R. Fischer states that the story describes conflicts that arose in the 17th century due to the division of the island into competing clans. The Hanau momoko were people from "a western apu", while the Hanau epe were from Poike. The story "recalls the division of the island into the two competing hanau of the Tu'u and the 'Otu 'Iti. It is possible that the legend recalls an actual conflict that took place north of Tongariki between these two 'nations', perhaps as early as the sixteenth century."[1]

It has also been argued that the difference was one of class, not race, territory or culture. One view is that the "thin" or "short eared" Hanau momoko were of lower social status, while the well-fed "sturdy" or adorned "long eared" Hanau epe were the ruling class.[7] Thomas Barthel, who studied the oral traditions of the island, argued, in contrast, that the Hanau epe were the subordinated group, settled at Poike away from the principal centre of power.[7]

Cultural references

The struggle between the Long Ears and Short Ears is the central element in the plot of the 1994 epic film Rapa Nui, in which the two groups are depicted as a ruling elite (Long Ears) and oppressed labourers (Short Ears). This is anachronistically combined with other Easter Island traditions, in particular the race for the sooty tern's egg in the Birdman Cult. These are all linked to the history of the island's deforestation.[6]

References

- 1 2 3 Steven R. Fischer, Island at the End of the World: The Turbulent History of Easter Island, Reaktion Books, 2005, p.42.

- ↑ This version was recorded by Doctor J.L. Palmer in 1868. See Heyerdahl. However, the legends may be influenced by the situation of the 1860s: fierce fighting ensued on the island when the remaining population and returning immigrants fought for the land and resources.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rupert Ivan Murrill, Cranial and Postcranial Skeletal Remains from Easter Island, University of Minnesota Press, 1968, p.67.

- ↑ The "Hanau Eepe", their Immigration and Extermination.

- ↑ Englert, Sebastian, 1993. La tierra de Hotu Matu‘a — Historia y Etnología de la Isla de Pascua, Gramática y Diccionario del antiguo idioma de la isla. Sexta edición aumentada. (The Land of Hotu Matu‘a — History and Ethnology of Easter Island, Grammar and Dictionary of the Old Language of the Island. Sixth expanded edition.) Santiago de Chile: Editorial Universitaria.

- 1 2 William R. Long, "Does 'Rapa Nui' Take Artistic License Too Far?", Los Angeles Times, Friday August 26, 1994, p.21.

- 1 2 3 John Flenley, Paul G. Bahn, The Enigmas of Easter Island: Island on the Edge, Oxford University Press, 2003, pp.76; 154.

- ↑ Heyderdahl, Thor. Easter Island - The Mystery Solved. Random House New York 1989.

- ↑ Robert C. Suggs, "Kon-Tiki", in Rosemary G. Gillespie, D. A. Clague (eds), Encyclopedia of Islands, University of California Press, 2009, pp.515-16.

- ↑ Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, Penguin, London (2005), pp 86-90.