Hanafi

| |

|---|

|

|

Lists |

| Islam portal |

The Hanafi (Arabic: حنفي Ḥanafī) school is one of the four religious Sunni Islamic schools of jurisprudence (fiqh).[1] It is named after the scholar Abū Ḥanīfa an-Nu‘man ibn Thābit (d. 767), a tabi‘i whose legal views were preserved primarily by his two most important disciples, Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani. The other major schools of Sharia in Sunni Islam are Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.[2][3]

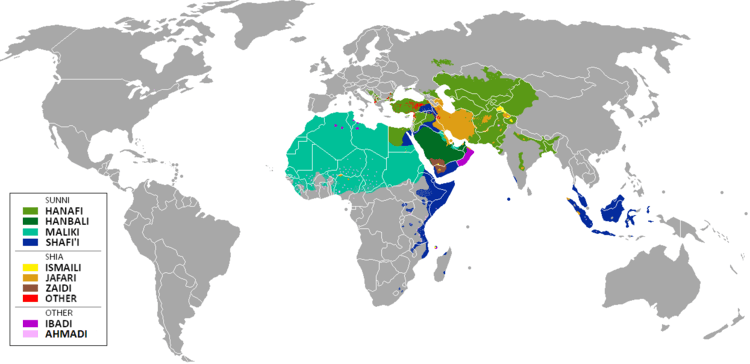

Hanafi is the fiqh with the largest number of followers among Sunni Muslims.[4] It is predominant in the countries that were once part of the historic Ottoman Empire and Sultanates of Turkic rulers in the Indian subcontinent, northwest China and Central Asia. In the modern era, Hanafi is prevalent in the following regions: Turkey, the Balkans, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt, parts of Iraq, the Caucasus, parts of Russia, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, parts of India and China, and Bangladesh.[4][5][6]

Sources and methodology

The sources from which the Hanafi madhhab derives Islamic law are, in order of importance and preference: the Quran, and the hadiths containing the words, actions and customs of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (narrated in six hadith collections, of which Sahih Bukhari and Sahih Muslim are the most relied upon); if these sources were ambiguous on an issue, then the consensus of the Sahabah community (Ijma of the companions of Muhammad), then individual's opinion from the Sahabah, Qiyas (analogy), Istihsan (juristic preference), and finally local Urf (local custom of people).[7]

Abu Hanifa is regarded by modern scholarship as the first to formally adopt and institute analogy (Qiyas) as a method to derive Islamic law when the Quran and hadiths are silent or ambiguous in their guidance.[8]

The foundational texts of Hanafi madhhab, credited to Abū Ḥanīfa and his students Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani, include Al-fiqh al-akbar (theological book on jurisprudence), Al-fiqh al-absat (general book on jurisprudence), Kitab al-athar (thousands of hadiths with commentary), Kitab al-kharaj and Kitab al-siyar (doctrine of war against unbelievers, distribution of spoils of war among Muslims, apostasy and taxation of dhimmi).[9][10][11]

History

As the fourth Caliph, Ali had transferred the Islamic capital to Kufa, and many of the first generation of Muslims had settled there, the Hanafi school of law based many of its rulings on the earliest Islamic traditions as transmitted by first generation Muslims residing in Iraq. Thus, the Hanafi school came to be known as the Kufan or Iraqi school in earlier times. Ali and Abdullah, son of Masud formed much of the base of the school, as well as other personalities such as Muhammad al-Baqir, Ja'far al-Sadiq, and Zayd ibn Ali. Many jurists and historians had lived in Kufa including one of Abu Hanifa's main teachers, Hammad ibn Sulayman.

In the early history of Islam, Hanafi doctrine was not fully compiled. The fiqh was fully compiled and documented in the 11th century.[12]

The Turkish rulers were some of the earliest adopters of relatively more flexible Hanafi fiqh, and preferred it over the traditionalist Medina-based fiqhs which favored correlating all laws to Quran and Hadiths and disfavored Islamic law based on discretion of jurists.[13] The Abbasids patronized the Hanafi school from the 10th century onwards. The Seljuk Turkish dynasties of 11th and 12th centuries, followed by Ottomans adopted Hanafi fiqh. The Turkic expansion spread Hanafi fiqh through Central Asia and into South Asia, with the establishment of Seljuk Empire, Timurid dynasty, Khanates and Delhi Sultanate.[12][13]

Views

Apostasy

Hanafi madhhab consider apostasy, that is the act of leaving Islam or converting to another religion or becoming an atheist, a crime as well as a religious sin.[14][15][16] A male apostate must be put to death, if he does not repent and return to Islam, in Hanafi law; a female apostate must be imprisoned in solitary confinement and punished until she reverts to Islam.[17][18] Hanafi scholars recommend three days of imprisonment for male apostates before execution, although the delay before killing the former Muslim is not mandatory. Apostates who are men must be killed, states the Hanafi Sunni fiqh, while women must be held in solitary confinement and beaten every three days till they recant and return to Islam.[17]

Hanafi school, as with other Muslim fiqhs, considers apostasy as a civil liability as well.[17] Therefore, (a) the property of the apostate is seized and distributed to his or her Muslim relatives; (b) his or her marriage annulled (faskh); (c) any children removed and considered ward of the Islamic state.[17] In case the entire family has left Islam, or there are no surviving Muslim relatives recognized by Sharia, the apostate's property is liquidated by the Islamic state (part of fay, الْفيء). Women apostates, in Hanafi school, loses all inheritance rights.[19][20] Hanafi Sunni school of jurisprudence allows waiting till execution, before children and property are seized; other schools do not consider this wait as mandatory.[21]

Blasphemy

Hanafi law views blasphemy as synonymous with apostasy, and therefore, accepts the repentance of apostates. Those who refuse to repent, their punishment is death if the blasphemer is a Muslim man, and if the blasphemer is a woman, she must be imprisoned with coercion (beating) till she repents and returns to Islam.[22] If a non-Muslim commits blasphemy, his punishment must be a tazir (discretionary, can be death, arrest, caning, etc.).[23][24]

Stoning

Hanafi jurists have held that the accused must be a muhsan at the time of religiously disallowed sex, to be punished by rajm (stoning).[26] A muhsan is an adult, free, Muslim who has previously enjoyed legitimate sexual relations in matrimony, regardless of whether the marriage still exists.[27] In other words, stoning does not apply to someone who was never married in his or her life (only lashing in public is the mandatory punishment in such cases).[26] For evidence, Hanafi fiqh accepts the following: self-confession or testimony of four male witnesses (female witness is not acceptable). In cases of self-confession, the accused is neither bound nor partially buried and allowed to escape during stoning. In the other case, according to Hanafi legal texts, the accused is bound and partially buried inside a bit in standing position so he or she cannot escape, and then stoning must be performed till he or she dies.[26]

Hanafi scholars specify the stone to be used should be the size of one's hand. It should not be too large to cause death too quickly, nor too small to extend only pain.[26]

Violence

Hanafi legal school has discussed violence and its appropriateness. This discussion has been controversial and with disagreements. Some modern Hanafi scholars state the requirement of peaceful methods while some insist that neither self-defense nor action against oppression is terrorism.[28] Historical Hanafi scholars have stated that all violence is justified when it benefits Muslims and Islam. For example, the 18th-19th century Hanafi jurist Ibn Abidin supported violence,[28] and his argument has been explained by other Hanafi scholars as follows:

The attacker's purpose should not be suicide. He should have the impression (guman) that he would succeed, or that damage would be inflicted on the enemy, or that the Muslims would be emboldened. The effects of the attack are to be measured either by the attacker himself or by his commander. The purpose of the attack is the elevation of religion or of God's word, not personal ambition, pride, or tribal or national sentiment.

- – Mujib al-Rahman[28]

In early Islamic era, another Hanafi scholar al-Jassas states that pre-emptive killing is justified when reprimands fail and before the enemy or individual commits a deed that is evil in Islam; however, the enemy or likely wrongdoer should not be killed if one's own life is likely to be lost in the effort.[29] Other Hanafi and other fiqh scholars, such as the Shafi'i scholar Wahba Zuhayli suggest peaceful methods are necessary when Muslim community faces an oppressive government and unjust laws.[28]

Theory of perennial war

The 11th century Hanafi scholar Sarakhsi adopted Shafi'i doctrine of war which was first to justify, in Islamic theory, that the proper reason to wage war, jihad, on unbelievers, was their disbelief (kufr).[30][31] War must be waged, Shafi'i scholars stated, not merely when the unbelievers attacked or actively started a conflict with Muslims, but the unbelievers must be attacked "wherever Muslims may find them", because they are unbelievers. Hanafi scholars, such as Sarakhsi in his Kitab al-Mabsut, accepted this theory and ruled that Muslims must fight the unbelievers as "a duty enjoined permanently until the end of time".[30] Similarly, Hanafi texts such as Al-Hidayah based on Al-Quduri's Mukhtasar states,

Fighting unbelievers is obligatory, even if they do not initiate it against us.

- – Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad Qudūrī, 11th century Hanafi scholar[32]

The rationale for holy war against unbelievers set by early Hanafi scholars continued for many centuries. For example, Ebussuud Efendi of 16th century, provided ideological framework to Ottoman Sultans to raid and attack non-Muslim territories for holy war.[33] However, this historical interpretation and justification for jihad and unprovoked war from Quran and Hadiths, has been challenged by some modern Islamic scholars.[34]

Slavery

Hanafi scholars derived slave law statutes for the numerous domestic and agricultural slaves in Ottoman Empire.[33] These included, like other fiqhs, laws on master's ownership rights, lack of property rights for the slaves, right of male masters to have sex with female slaves, hereditary slavery for children of slaves, as well as procedures for manumission of slaves who convert to Islam.[35] However, a distinct feature of Hanafi slave code was the grant of special rights to soldier slaves of Sultan, who were called Mamluks and Janissaries. These special slaves served as governors, officials and army commanders on the behalf of Ottoman Empire rulers.[33][36]

Sultan's slaves, unlike common slaves, had separate rights, were awarded a large portion of the booty collected during raids on and war with unbelievers (Ghanima). Some of these ruler's slaves later founded their own dynasties and Islamic Sultanates in Egypt, Iraq and India.[37][38][39]

Other views

- The Hanafi school permits a man or a woman, after puberty, to marry without getting permission of a wali (guardian); the permission is a requirement for adult Muslim women in other Islamic fiqhs such as Maliki, Hanbali, Shafii, Fatimid Shias, Daudi and Bohras.[40] However, Hanafi school grants a guardian the right to arrange and give away in marriage, a minor girl before puberty, without anyone's consent.[41][42]

- Majority of scholars from the Hanafi school of thought agree that the feet of a female are not part of the awrah and therefore may be revealed.[43] Feet are parts of awrah of a female in Maliki, Hambali, Shafii, and Shia.

- The dominant opinion in the Hanafi school says the time of Asr prayer begins when the length of any object's shadow is twice the length of the object plus the length of that object's shadow at noon. Meanwhile, the Maliki, Shafi`i, and Hanbali schools say it is at the time when the length of any object's shadow equals the length of the object itself plus the length of that object's shadow at noon.

- Abu Hanifa, the founder of Hanafi school, states that a divorced wife loses her right to dower property (brideprice) in khula and mubaraa forms of divorce. Later Hanafi scholars partially or wholly disagreed with Hanifa, and left to sharia courts the discretion to decide.[44] In either case, this dispute is limited to rights relating to dower (mahr), the divorced wife has no rights in the wealth her divorced husband gained during marriage.[44]

- Hanafi school considers the marriage of a person, even if it was coerced, as valid, a position a few Hanafi scholars disagreed with.[45] Hanafi sharia is also more restrictive, than other Islamic fiqhs, in the rights it gives a Muslim woman to terminate her marriage.[46] She can ask a sharia court to annul the marriage on the grounds that her husband is impotent and unable to consummate the marriage, or that her husband is missing and presumed dead. In the second case, Hanafi law requires her to wait for very long periods, often till the natural age of missing man is over, sometimes four years, or at the discretion of the court.[46][47]

- Hanafi scholars consider a child born within two years of a husband's death or a woman's divorce, as legitimate and from her dead/previous husband. This Hanafi law was upheld in 20th century by influential muftis.[48]

- Hanafi jurists allow Muslim scholars to charge money for anyone wanting to learn Quran.[49] Many Hanafi law interpretations also allowed people to charge interest for any loan they give, a practice that is not supported in other Islamic legal schools for sharia-compliant finance.[49]

- The Hanafi school forbids any alcohol containing drinks that were produced from date or vine (grapes).[50] However, it permits consumption of alcoholic beverages from non-date and non-vine sources, under the conditions that it is not consumed in vain, or to a point where it will intoxicate.[51] Intoxication from any sources is considered religiously unlawful and that must be punished.[52][53]

- Painting of a picture of any living thing (taswir), as well as sculpture of human beings or animals (anything with a head) from any material, was forbidden and declared unlawful by Hanafi scholars.[54][55]

- Music, dancing and singing was stated to be unlawful under sharia by Hanafi scholars, a religious position shared by most other Sunni fiqhs.[56][57]

- The Hanafi school permits appointing female judges.[58]

- Women are not permitted to pray next to men, or lead men in prayer, with the Hanafi school's justification that "men have a degree of precedence over women" from Quranic verse 2:228.[59][60] By 13th century, Hanafi scholars did not allow Muslim women, of any age, to go to mosques, because noted 'Abd Allah al-Mawsili, "of the corruption of the times and the open commission of obscene acts."[61] This view was later adopted by other Islamic fiqhs such as Maliki in 14th century and Shafi'i in 15th century. In contemporary times, Hanafi scholars allow Muslim women to go to mosques, but cannot lead prayers by men, and are permitted but considered makruh (disliked) to lead prayers by other women.[62]

- The Hanafi school considers admission in a court of law to be divisible; that is, a plaintiff could accept some parts of a defendant's testimony while rejecting other parts. This position is also held by the Maliki school, though it is opposed by the Zahiris and the majority of the Hanbalis.[63]

See also

- Islamic schools and branches

- List of major Hanafi books

- List of Hanafis

- Sharia

- Apostasy in Islam

- Salat

- Islamic views on sin

References

- ↑ Hisham M. Ramadan (2006), Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 978-0759109919, p. 24-29

- ↑ Gregory Mack, Jurisprudence, in Gerhard Böwering et al (2012), The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691134840, p. 289

- ↑ Sunnite Encyclopedia Britannica (2014)

- 1 2 3 4 Jurisprudence and Law - Islam Reorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)

- 1 2 Siegbert Uhlig (2005), "Hanafism" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha, Vol 2, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447052382, pp. 997-999

- ↑ Abu Umar Faruq Ahmad (2010), Theory and Practice of Modern Islamic Finance, ISBN 978-1599425177, pp. 77-78

- ↑ Hisham M. Ramadan (2006), Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 978-0759109919, p. 26

- ↑ See:

*Reuben Levy, Introduction to the Sociology of Islam, pg. 236-237. London: Williams and Norgate, 1931-1933.

*Chiragh Ali, The Proposed Political, Legal and Social Reforms. Taken from Modernist Islam 1840-1940: A Sourcebook, pg. 280. Edited by Charles Kurzman. New York City: Oxford University Press, 2002.

*Mansoor Moaddel, Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse, pg. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

*Keith Hodkinson, Muslim Family Law: A Sourcebook, pg. 39. Beckenham: Croom Helm Ltd., Provident House, 1984.

*Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, edited by Hisham Ramadan, pg. 18. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

*Christopher Roederrer and Darrel Moellendorf, Jurisprudence, pg. 471. Lansdowne: Juta and Company Ltd., 2007.

*Nicolas Aghnides, Islamic Theories of Finance, pg. 69. New Jersey: Gorgias Press LLC, 2005.

*Kojiro Nakamura, "Ibn Mada's Criticism of Arab Grammarians." Orient, v. 10, pgs. 89-113. 1974 - ↑ Oliver Leaman (2005), The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0415326391, pp. 7-8

- ↑ Kitab Al-Athar of Imam Abu Hanifah, Translator: Abdussamad, Editors: Mufti 'Abdur Rahman Ibn Yusuf, Shaykh Muhammad Akram (Oxford Centre of Islamic Studies), ISBN 978-0954738013

- ↑ Majid Khadduri (1966), The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801869754

- 1 2 Nazeer Ahmed, Islam in Global History, ISBN 978-0738859620, pp. 112-114

- 1 2 John L. Esposito (1999), The Oxford History of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195107999, pp. 112-114

- ↑ Mohamed El-Awa (1993), Punishment in Islamic Law, American Trust Publications, ISBN 978-0892591428, pp 1-68

- ↑ Frank Griffel (2001), Toleration and exclusion: al-Shafi ‘i and al-Ghazali on the treatment of apostates, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64(03): 339-354

- ↑ David Forte, Islam’s Trajectory, Revue des Sciences Politiques, No. 29 (2011), pages 92-101

- 1 2 3 4 Peters & De Vries (1976), Apostasy in Islam, Die Welt des Islams, Vol. 17, Issue 1/4, pp 1-25

- ↑ Heffening, W. (1993). "Murtadd". In C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs; et al. Encyclopaedia of Islam 7. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 635–6. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- ↑ Samuel M. Zwemer, The law of Apostasy, The Muslim World, Volume 14, Issue 4, pp. 373–391

- ↑ Kazemi F. (2000), Gender, Islam, and politics, Social Research, Vol. 67, No. 2, pages 453-474

- ↑ Peters & De Vries (1976), Apostasy in Islam, Die Welt des Islams, Vol. 17, Issue 1/4, pp 7-8

- ↑

- Abu al-Layth al-Samarqandi (983), Mukhtalaf al-Riwayah, vol. 3, pp. 1298–1299

- Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Tahawi (933), Mukhtasar Ikhtilaf al-Ulama, vol. 3, p. 504

- Ali ibn Hassan al-Sughdi (798); Kitab al-Kharaj; Quote: “أيما رجل مسلم سب رَسُوْل اللهِ صَلَّى اللهُ عَلَيْهِ وَسَلَّمَ أو كذبه أو عابه أوتنقصه فقد كفر بالله وبانت منه زوجته ، فإن تاب وإلا قتل ، وكذلك المرأة ، إلا أن أبا حنيفة قَالَ: لا تقتل المرأة وتجبر عَلَى الإسلام”; Translation: “A Muslim man who blasphemes the Messenger of Allah, denies him, reproaches him, or diminishes him, he has committed apostasy in Allah, and his wife is separated from him. He must repent, or else is killed. And this is the same for the woman, except Abu Hanifa said: Do not kill the woman, but coerce her back to Islam.”

- ↑ Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Tahawi (933), Mukhtasar Ikhtilaf al-Ulama, vol. 3, p. 504

- ↑ P Smith (2003), Speak No Evil: Apostasy, Blasphemy and Heresy in Malaysian Syariah Law, UC Davis Journal Int'l Law & Policy, 10, pp. 357-373;

- N Swazo (2014), The Case Of Hamza Kashgari: Examining Apostasy, Heresy, And Blasphemy Under Sharia, The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 12(4), pp. 16-26

- ↑ Jamal Malik (2008), Islam in South Asia: A Short History, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004168596, pp. 194-197

- 1 2 3 4 Elyse Semerdjian (2008), "Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0815631736, pp. 22-23

- ↑ Muhsan The Oxford Dictionary of Islam (2012)

- 1 2 3 4 Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, p. 298-299, 262-267

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, p. 228-230

- 1 2 Majid Khadduri (2001), The Islamic Law of Nations, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801869754, p. 58

- ↑ Elfatih Salam (2006), Islamic Doctrine of Peace and War, The Int'l Stud. Journal, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp 43-74

- ↑ The Mukhtasar Al-Quduri: A Manual of Islamic Law According to the Hanafi School, Abia Afsar Siddiqui (Translator), Ta-Ha Publishers, ISBN 978-1842001189, p. 661

- 1 2 3 Colin Imber, Ebu's-suùd: The Islamic Legal Tradition, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0748607679, pp. 77-80

- ↑ Ma'n H. Abdul-Rahman (2004), UNTYING THE GORDIAN KNOT: IS JIHAD THE BELLUM JUSTUM OF ISLAM?: IS JIHAD A JUST WAR? WAR, PEACE, AND HUMAN RIGHTS UNDER ISLAMIC AND PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW (STUDIES IN RELIGION AND SOCIETY, VOL. 53, Emory International Law Review, Vol. 18, pp. 493-494.

- ↑ K Ali (2010), Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674050594, pp. 165-197

- ↑ Reuben Levy (1957), The Social Structure of Islam, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521091824, pp. 368-398

- ↑ Jane Hathaway (1995), The Military Household in Ottoman Egypt, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 39–52, doi:10.1017/s0020743800061572

- ↑ Stanford Shaw (1976), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Vol. I), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521291637

- ↑ Peter Jackson (1990), The Mamlūk institution in early Muslim India, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, Vol. 122, No. 2, pp 340-358

- ↑ Otto, Jan Michiel. Sharia and National Law in Muslim Countries. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-8728-048-2.

- ↑ Syed Mohammed Ali (2004), The Position of Women in Islam: A Progressive View, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791460962, pp. 40-41

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, p. 181

- ↑ "Religions - Islam: Hijab". BBC. 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

- 1 2 Syed Mohammed Ali (2004), The Position of Women in Islam: A Progressive View, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791460962, pp. 66-68

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, p. 191-194

- 1 2 Syed Mohammed Ali (2004), The Position of Women in Islam: A Progressive View, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791460962, pp. 73-76

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, pp. 183-184

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, pp. 181-182

- 1 2 Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012), Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107096455, pp. 121-122

- ↑ Sahih Muslim, 023:4893

- ↑ Malise Ruthven (23 October 1997). Islam: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-0-19-154011-0.

- ↑ John Andrew Morrow (11 November 2013). Islamic Images and Ideas: Essays on Sacred Symbolism. McFarland. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-4766-1288-1.

Therefore, it was not the substances that led to these transgressions, just the intoxication. That explains why the Hanafi and Mutazili stilll concur that consuming any substance to induce a state of intoxication is prohibited and liable to punishment.

- ↑ Ibn Rushd Qurtubi al-Maliki [Averroès] (1994). The distinguished jurist's primer: a translation of Bidāyat al-mujtahid Wa Nihayat Al-Muqtasid. Centre for Muslim Contribution to Civilization.

- ↑

- TW Arnold, An Indian Picture of Muhammad and his Companions, p. 249, at Google Books, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 34, p. 249;

- Rudi Paret (1960), Textbelege zum Islamischen Bilderverbot, in Das Werk des Künstlers, Studien H. Schrade dargebracht, Stuttgart, pp. 36-48

- ↑ Zaky Hassan (1944), The attitude of Islam towards painting, Bulletin of the Faculty ofArts (Cairo University), Vol. 7, pp. 1-15;

Isa Salman (1969), Islam and figurative arts, Sumer, Vol. 25, pp. 59-96 - ↑ L. Ali Khan and Hisham M. Ramadan (2011), Contemporary Ijtihad: Limits and Controversies, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0748641284, pp. 72-75

- ↑ M Cook (2010), Commanding Right and Forbidding Wrong in Islamic Thought, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521130936, pp. 91-103, 145-182;

Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:15:72,

Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:69:494v,

Sunan Abu Dawood, 34:4218,

Quran 53:61 - ↑ Nigeria "Political Shariʼa"?: Human Rights and Islamic Law in Northern Nigeria, Carina Tertsakian - 2004, p 64

- ↑ Marion Katz (2013), Prayer in Islamic Thought and Practice, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521887885, pp 184-185

- ↑ Quran 2:228

- ↑ Marion Katz (2013), Prayer in Islamic Thought and Practice, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521887885, pp 199-202

- ↑ Juliane Hammer, American Muslim Women, Religious Authority, and Activism, University of Texas Press, ISBN 978-0292735552, p. 83

- ↑ Ṣubḥī Rajab Maḥmaṣānī, Falsafat al-tashrī fī al-Islām, pg. 175. Trns. Farhat Jacob Ziadeh. Leiden: Brill Archive, 1961.

Further reading

- Branon Wheeler, Applying the Canon in Islam: The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretive Reasoning in Ḥanafī Scholarship (Albany, SUNY Press, 1996).

- Nurit Tsafrir, The History of an Islamic School of Law: The Early Spread of Hanafism (Harvard, Harvard Law School, 2004) (Harvard Series in Islamic Law, 3).

- Behnam Sadeghi (2013), The Logic of Law Making in Islam: Women and Prayer in the Legal Tradition, Cambridge University Press, Chapter 6 - The Historical Development of Hanafi Reasoning, ISBN 978-1107009097

- Theory of Hanafi law: Kitab Al-Athar of Imam Abu Hanifah, Translator: Abdussamad, Editors: Mufti 'Abdur Rahman Ibn Yusuf, Shaykh Muhammad Akram (Oxford Centre of Islamic Studies), ISBN 978-0954738013

- Hanafi theory of war and taxation: Majid Khadduri (1966), The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801869754

External links

- Hanafiyya Bulend Shanay, Lancaster University

- Kitab al-siyar al-saghir (Summary version of the Hanafi doctrine of War) Muhammad al-Shaybani, Translator - Mahmood Ghazi

- The Legal Aspects of Marriage according to Hanafi Fiqh Islamic Quarterly London, 1985, vol. 29, no4, pp. 193–219

- Al-Hedaya, A 12th century compilation of Hanafi fiqh-based religious law, by Burhan al-Din al-Marghinani, Translated by Charles Hamilton

- Development of family law in Afghanistan: The role of the Hanafi Madhhab Central Asian Survey, Volume 16, Issue 3, 1997

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||