H-alpha

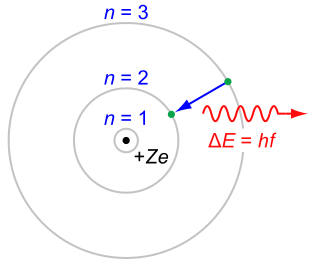

transition depicted here produces an H-alpha photon, and the first line of the Balmer series. For hydrogen (

transition depicted here produces an H-alpha photon, and the first line of the Balmer series. For hydrogen ( ) this transition results in a photon of wavelength 656 nm (red).

) this transition results in a photon of wavelength 656 nm (red).H-alpha (Hα) is a specific deep-red visible spectral line in the Balmer series created by hydrogen with a wavelength of 656.28 nm, which occurs when a hydrogen electron falls from its third to second lowest energy level. H-alpha light is important to astronomers as it is emitted by many emission nebulae and can be used to observe features in the sun's atmosphere including solar prominences.

Balmer series

According to the Bohr model of the atom, electrons exist in quantized energy levels surrounding the atom's nucleus. These energy levels are described by the principal quantum number n = 1, 2, 3, ... . Electrons may only exist in these states, and may only transit between these states.

The set of transitions from n ≥ 3 to n = 2 is called the Balmer series and its members are named sequentially by Greek letters:

- n = 3 to n = 2 is called Balmer-alpha or H-alpha,

- n = 4 to n = 2 is called Balmer-beta or H-beta,

- n = 5 to n = 2 is called Balmer-gamma or H-gamma, etc.

For the Lyman series the naming convention is:

- n = 2 to n = 1 is called Lyman-alpha,

- n = 3 to n = 1 is called Lyman-beta, etc.

H-alpha has a wavelength of 656.281 nm,[1] is visible in the red part of the electromagnetic spectrum, and is the easiest way for astronomers to trace the ionized hydrogen content of gas clouds. Since it takes nearly as much energy to excite the hydrogen atom's electron from n = 1 to n = 3 as it does to ionize the hydrogen atom, the probability of the electron being excited to n = 3 without being removed from the atom is very small. Instead, after being ionized, the electron and proton recombine to form a new hydrogen atom. In the new atom, the electron may begin in any energy level, and subsequently cascades to the ground state (n = 1), emitting photons with each transition. Approximately half the time, this cascade will include the n = 3 to n = 2 transition and the atom will emit H-alpha light. Therefore, the H-alpha line occurs where hydrogen is being ionized.

The H-alpha line saturates (self-absorbs) relatively easily because hydrogen is the primary component of nebulae, so while it can indicate the shape and extent of the cloud, it cannot be used to accurately determine the cloud's mass. Instead, molecules such as carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, ammonia, or acetonitrile are typically used to determine the mass of a cloud.

Filter

A hydrogen-alpha filter is an optical filter designed to transmit a narrow bandwidth of light generally centred on the H-alpha wavelength. They are characterized by a bandpass width that measures the width of the wavelength band that is transmitted.[2] These filters can be dichroic filters manufactured by multiple (~50) vacuum-deposited layers. These layers are selected to produce interference effects that filter out any wavelengths except at the requisite band.[3]

Taken in isolation, H-alpha dichroic filters are useful in astrophotography and for reducing the effects of light pollution. They do not have narrow enough bandwidth for observing the sun's atmosphere.

For observing the sun, a much narrower band filter can be made from three parts: an "energy rejection filter" which is usually a piece of red glass that absorbs most of the unwanted wavelengths, a Fabry–Pérot etalon which transmits several wavelengths including one centred on the H-alpha emission line, and a "blocking filter" -a dichroic filter which transmits the H-alpha line while stopping those other wavelengths that passed through the etalon. This combination will pass only a narrow (<0.1 nm) range of wavelengths of light centred on the H-alpha emission line.

The physics of the etalon and the dichroic interference filters are essentially the same (relying on constructive/destructive interference of light reflecting between surfaces), but the implementation is different (a dichroic interference filter relies on the interference of internal reflections while the etalon has a relatively large air gap). Due to the high velocities sometimes associated with features visible in H-alpha light (such as fast moving prominences and ejections), solar H-alpha etalons can often be tuned (by tilting or changing the temperature) to cope with the associated Doppler effect.

Commercially available H-alpha filters for amateur solar observing usually state bandwidths in Angstrom units and are typically 0.7Å (0.07 nm). By using a second etalon, this can be reduced to 0.5Å leading to improved contrast in details observed on the sun's disc.

An even more narrow band filter can be made using a Lyot filter.

See also

References

- ↑ A. N. Cox, editor (2000). Allen's Astrophysical Quantities. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98746-0.

- ↑ "Filters". Astro-Tom.com. Retrieved 2006-12-09.

- ↑ D. B. Murphy, K. R. Spring, M. J. Parry-Hill, I. D. Johnson, M. W. Davidson. "Interference Filters". Olympus. Retrieved 2006-12-09.