HMHS Britannic

His Majesty's Hospital Ship (HMHS) Britannic | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMHS Britannic |

| Owner: |

|

| Operator: |

|

| Port of registry: |

|

| Builder: | Harland and Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number: | 433 |

| Laid down: | 30 November 1911 |

| Launched: | 26 February 1914 |

| Completed: | 12 December 1915 |

| In service: | 23 December 1915 (hospital ship) |

| Out of service: | 21 November 1916 |

| Fate: | Sank after an explosion on 21 November 1916 near Kea in the Aegean Sea. |

| Status: | Wreck |

| General characteristics | |

| Class & type: | Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 48,158 gross register tons |

| Displacement: | 53,200 tons |

| Length: | 882 ft 9 in (269.06 m) |

| Beam: | 92 ft (28.0 m) |

| Height: | 175 ft (53 m) from the keel to the top of the funnels |

| Draught: | 34 ft 7 in (10.5 m) |

| Depth: | 64 ft 6 in |

| Decks: | 9 passenger decks |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Capacity: | 3309 wounded |

HMHS Britannic was the third, last-built, and largest member of the White Star Line's Olympic class of vessels. She was the sister ship of RMS Olympic and RMS Titanic, and was intended to enter service as the transatlantic passenger liner, RMS Britannic. The White Star Line used Britannic as the name of two other ships: SS Britannic (1874), holder of the Blue Riband and MV Britannic (1929), a motor liner, owned by White Star and then Cunard, scrapped in 1960.

Britannic was launched just before the start of the First World War and was laid up at her builders in Belfast for many months before being put to use as a hospital ship in 1915. She was shaken by an explosion, caused by an underwater mine, in the Kea Channel off the Greek island of Kea on the morning of 21 November 1916, and sank 55 minutes later, killing 30 people.

There were 1,065 people on board; the 1,035 survivors were rescued from the water and lifeboats. Britannic was the largest ship lost in the First World War. The vessel is also currently the largest passenger ship on the sea floor.

History

Post-Titanic design changes

Following the loss of Titanic and the subsequent inquiries, several design changes were made to the remaining Olympic-class liners. With Britannic, these changes were made before launching. (Olympic was refitted on her return to Harland and Wolff.) The main changes included the introduction of a double hull along the engine and boiler rooms and raising six out of the 15 watertight bulkheads up to B Deck. A more obvious external change was the fitting of large crane-like davits, each capable of holding six lifeboats. Additional lifeboats could be stored within reach of the davits on the deck house roof, and in an emergency the davits could even reach lifeboats on the other side of the ship. The aim of this design was to enable all the lifeboats to be launched, even if the ship developed a list that would normally prevent lifeboats being launched on the side opposite to the list. However, several of these davits were placed abreast of funnels, defeating that purpose.[2] Similar davits were not fitted to Olympic. The ship carried 48 lifeboats, capable of carrying at least 75 people each. Thus, 3,600 people could be carried by the lifeboats, more than the maximum number of people the ship could carry. In the ship's sinking, only 37 of them were lowered (but two were lost in the propellers, along with their occupants), meaning that 11 of them were not used; this was not a problem at all because the ship carried only about a third of the people that could be carried, so that none of the used lifeboats were full.

Britannic's hull was also 2 feet (0.6 m) wider than her predecessors, following the redesign after the loss of Titanic. To keep to a 21-knot (39 km/h; 24 mph) service speed, the shipyard installed a larger turbine rated for 18,000 horsepower (13,000 kW)—versus Olympic's and Titanic's 16,000 horsepower (12,000 kW) turbine—to compensate for the ship's extra width.

Divers featured in a 2006 History Channel special about Titanic discovered that the expansion joints on Britannic were of an improved, pear-shaped design, unlike the v-shaped expansion joints of Titanic.[3]

Rumoured name-change

Although the White Star Line and the Harland and Wolff shipyard always denied it,[2][4] some sources claim that the ship was to be named Gigantic.[5] One such famous source is a poster of the ship with the name Gigantic at the top.[6] According to Simon Mills, owner of the Britannic wreck, a copy of the Harland and Wolff order book dated October 1911 (about six months before the Titanic disaster) already shows the name Britannic. Tom McCluskie stated that in his capacity as Archive Manager and Historian at Harland and Wolff, he "never saw any official reference to the name 'Gigantic' being used or proposed for the third of the Olympic class vessels".[7][8] Some hand-written changes were added to the order book and dated January 1912. These only dealt with the ship's moulded width, not her name.[8] However, at least one set of documentation exists, in which Hingley's discuss the order for the ship's anchors; this documentation states that the name of the ship is Gigantic. It seems unlikely that this name was picked from press speculation of the day and it seems more likely that the name must have been used in correspondence with Harland and Wolff, albeit informally, before being quietly dropped.[9]

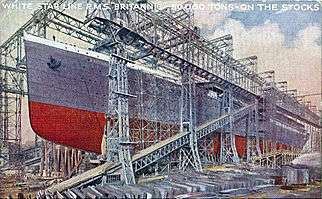

Construction

The keel for Britannic was laid on 30 November 1911 at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, 13 months after the launch of the Olympic. Due to improvements introduced as a consequence of the Titanic disaster, Britannic was not launched until 26 February 1914, which was filmed along with the fitting of a funnel.[10] Fitting out began subsequently. She was constructed in the same gantry slip used to build RMS Olympic. Reusing Olympic's space saved the shipyard time and money by not clearing out a third slip similar in size to those used for Olympic and Titanic. In August 1914, before Britannic could commence transatlantic service between New York and Southampton, the First World War began. Immediately, all shipyards with Admiralty contracts were given top priority to use available raw materials. All civil contracts (including the Britannic) were slowed down. The naval authorities requisitioned a large number of ships as armed merchant cruisers or for troop transport. The Admiralty was paying the companies for the use of their ships but the risk of losing a ship in naval operations was high. However, the big ocean liners were not taken for naval use, because the smaller ships were much easier to operate. White Star decided to withdraw RMS Olympic from service until the danger had passed. RMS Olympic returned to Belfast on 3 November 1914, while work on her sister continued slowly. All this would change in 1915.

Requisitioning

.jpg)

The need for increased tonnage grew critical as naval operations extended to the Eastern Mediterranean. In May 1915, Britannic completed mooring trials of her engines, and was prepared for emergency entrance into service with as little as four weeks notice. The same month also saw the first major loss of a civilian ocean ship when the Cunard liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed near the Irish coast by SM U-20.

The following month, the British Admiralty decided to use recently requisitioned passenger liners as troop transports in the Gallipoli campaign (also called the Dardanelles service). The first to sail were Cunard's RMS Mauretania and RMS Aquitania. As the Gallipoli landings proved to be disastrous and the casualties mounted, the need for large hospital ships for treatment and evacuation of wounded became evident. RMS Aquitania was diverted to hospital ship duties in August (her place as a troop transport would be taken by the RMS Olympic in September). Then on 13 November 1915, Britannic was requisitioned as a hospital ship from her storage location at Belfast. Repainted white with large red crosses and a horizontal green stripe, she was renamed HMHS (His Majesty's Hospital Ship) Britannic and placed under the command of Captain Charles A. Bartlett (1868–1945).

Last voyage

After completing five successful voyages to the Middle Eastern theatre and back to the United Kingdom transporting the sick and wounded, Britannic departed Southampton for Lemnos at 14:23 on 12 November 1916, her sixth voyage to the Mediterranean Sea. The Britannic passed Gibraltar around midnight on 15 November and arrived at Naples on the morning of 17 November, for her usual coaling and water refuelling stop, completing the first stage of her mission.

A storm kept the ship at Naples until Sunday afternoon, when Captain Bartlett decided to take advantage of a brief break in the weather and continue on. The seas rose once again just as Britannic left the port. However, by next morning, the storms died and the ship passed the Strait of Messina without problems. Cape Matapan was rounded in the first hours of Tuesday, 21 November. By the morning, Britannic was steaming at full speed into the Kea Channel, between Cape Sounion (the southernmost point of Attica, the prefecture that includes Athens) and the island of Kea.

There were a total of 1,065 people on board: 673 crew, 315 RAMC and 77 nurses.[11]

Explosion

At 08:12 on 21 November 1916, a loud explosion shook the ship.[12] The cause, whether it was a torpedo from an enemy submarine or a mine, was not apparent. The reaction in the dining room was immediate; doctors and nurses left instantly for their posts. Not everybody reacted the same way, as further aft, the power of the explosion was less felt, and many thought the ship had hit a smaller boat. Captain Bartlett and Chief Officer Hume were on the bridge at the time, and the gravity of the situation was soon evident.[13] The explosion was on the starboard[13] side, between holds two and three. The force of the explosion damaged the watertight bulkhead between hold one and the forepeak.[12] The first four watertight compartments were filling rapidly with water,[12] the boiler-man's tunnel connecting the firemen's quarters in the bow with boiler room six was seriously damaged, and water was flowing into that boiler room.[12]

Bartlett ordered the watertight doors closed, sent a distress signal, and ordered the crew to prepare the lifeboats.[12] Along with the damaged watertight door of the firemen's tunnel, the watertight door between boiler rooms six and five failed to close properly for an unknown reason.[12] Water was flowing further aft into boiler room five. Britannic had reached her flooding limit. She could stay afloat (motionless) with her first six watertight compartments flooded. There were five watertight bulkheads rising all the way up to B-deck.[14] Those measures had been taken after the Titanic disaster. (Titanic could float with her first four compartments flooded.) The next crucial bulkhead between boiler rooms five and four and its door were undamaged and should have guaranteed the ship's survival. However, there were open portholes along the lower decks, which tilted underwater within minutes of the explosion. The nurses had opened most of those portholes to ventilate the wards. As the ship's list increased, water reached this level and began entering aft from the bulkhead between boiler rooms five and four. With more than six compartments flooded, Britannic could not stay afloat.

Evacuation

On the bridge, Captain Bartlett was already considering efforts to save the ship, despite its increasingly dire condition. Only two minutes after the blast, boiler rooms five and six had to be evacuated. In about 10 minutes, Britannic was roughly in the same condition Titanic had been in one hour after the collision with the iceberg. Fifteen minutes after the ship was struck, the open portholes on E-deck were underwater. With water also entering the ship's aft section from the bulkhead between boiler rooms four and five, Britannic quickly developed a serious list to starboard due to the weight of the water flooding into the starboard side. With the shores of the Greek island Kea to the right, Bartlett gave the order to navigate the ship towards the island in attempt to beach the vessel. The effect of the ship's starboard list and the weight of the rudder made attempts to navigate the ship under its own power difficult, and the steering gear was knocked out by the explosion, which eliminated steering by the rudder. However, the captain ordered the port-side shaft driven at a higher speed than the starboard side, which helped the ship move towards the island.

Simultaneously, on the boat deck the crew members were preparing the lifeboats. Some of the boats were immediately rushed by a group of stewards and some sailors, who had started to panic. An unknown officer kept his nerve and persuaded his sailors to get out and stand by their positions near the boat stations. He decided to leave the stewards on the lifeboats because they were responsible for starting the panic, and he did not want them in his way in the evacuation. However, he left one of the crew with them to take charge of the lifeboat after leaving the ship. After this episode, all the sailors under his command remained at their posts until the last moment. As no Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) personnel were near this boat station at that time, the officer started to lower the boats, but when he saw that the ship's engines were still turning, he stopped them within 2 metres (6.6 ft) of the water and waited for orders from the bridge. The occupants of the lifeboats did not take this decision very well and started cursing. Shortly after this, orders finally arrived; no lifeboats should be launched, as the Captain had decided to try to beach Britannic at the nearby island.

Assistant Commander Harry William Dyke was making arrangements for lowering the lifeboats from the aft davits of the starboard boat deck when he spotted a group of firemen who had taken a lifeboat from the poop deck without authorisation and had not filled it to maximum capacity. Dyke ordered them to pick up some of the men who had already jumped into the water.

At 08:30, two lifeboats from the boat station assigned to Third Officer David Laws were lowered, without his knowledge, through the use of the automatic release gear. Those two lifeboats dropped some 2 metres (6 ft) and hit the water violently. The two lifeboats soon drifted back into the still-turning propellers, which were beginning to rise out of the water due to the water flooding into the front of the ship. As they reached the turning blades, both lifeboats, together with their occupants, were torn to pieces. Word of the carnage arrived on the bridge, and Captain Bartlett, seeing that water was entering more rapidly as Britannic was moving and that there was a risk of more victims, gave the order to stop the engines. The propellers stopped turning the moment a third lifeboat was about to be reduced to splinters. RAMC occupants of this boat pushed against the blades and got away from them safely.

Final moments

The Captain officially ordered the crew to lower the boats, and at 08:35, he gave the order to abandon ship. The forward set of port-side davits soon became useless. The unknown officer had already launched his two lifeboats and managed to launch rapidly one more boat from the aft set of portside davits. He then started to prepare the motor launch when First Officer Oliver came with orders from the Captain. Bartlett had ordered Oliver to get in the motor launch and use its speed to pick up survivors from the smashed lifeboats. Then he was to take charge of the small fleet of lifeboats formed around the sinking Britannic. After launching the motor launch with Oliver, the unknown officer filled another lifeboat with 75 men and launched it with great difficulty, because the port side was now very high from the surface because of the list to starboard. By 08:45, the list to starboard was so great that no davits were operable. The unknown officer with six sailors decided to move to mid-ship on the boat deck to throw overboard collapsible rafts and deck chairs from the starboard side. About 30 RAMC personnel who were still left on the ship followed them. As he was about to order these men to jump, then give his final report to the Captain, the unknown officer spotted Sixth Officer Welch and a few sailors near one of the smaller lifeboats on the starboard side. They were trying to lift the boat, but they had not enough men. Quickly, the unknown officer ordered his group of 40 men to assist the Sixth officer. Together they managed to lift it, load it with men, then launch it safely.

At 09:00, Bartlett sounded one last blast on the whistle then was washed overboard, as water had already reached the bridge. He swam to a collapsible boat and began to coordinate the rescue operations. The whistle blow was the final signal for the ship's engineers (commanded by Chief Engineer Robert Fleming) who, like their colleagues on Titanic, had remained at their posts until the last possible moment. They escaped via the staircase into funnel #4, which ventilated the engine room.

Britannic rolled over onto her starboard side, and the funnels began collapsing. Violet Jessop (who was also one of the survivors of Britannic's sister-ship Titanic, and had even been on the third sister, Olympic, when she collided with HMS Hawke) described the last seconds;

- "She dipped her head a little, then a little lower and still lower. All the deck machinery fell into the sea like a child's toys. Then she took a fearful plunge, her stern rearing hundreds of feet into the air until with a final roar, she disappeared into the depths, the noise of her going resounding through the water with undreamt-of violence...."

It was 09:07, only 55 minutes after the explosion. Britannic was the largest ship lost in the First World War.[15]

Rescue

Compared to Titanic, the rescue of Britannic was facilitated by three factors: the temperature was higher (21 °C (70 °F)[16] compared to −2 °C (28 °F)[17] for Titanic), more lifeboats were available (35 were launched and stayed afloat[18] compared to Titanic's 20[19]) and help was closer (arrived less than 2 hours after first distress call[18] compared to 3½ hours for Titanic[20]).

The first to arrive on the scene were the Greek fishermen from Kea on their caïque, who picked up many men from the water. One of the fishermen, Francesco Psilas, was later paid £4 by the Admiralty for his services. At 10:00, HMS Scourge sighted the first lifeboats and 10 minutes later stopped and picked up 339 survivors. HMS Heroic had arrived some minutes earlier and picked up 494. Some 150 had made it to Korissia (a community on Kea), where surviving doctors and nurses from Britannic were trying to save the injured men, using aprons and pieces of lifebelts to make dressings. A little barren quayside served as their operating room. Although the motor launches were quick to transport the wounded to Korissia, the first lifeboat arrived there some two hours later because of the strong current and their heavy load. It was the lifeboat of Sixth Officer Welch and an unknown officer. The latter was able to speak some French and managed to talk with one of the local villagers, obtaining some bottles of brandy and some bread for the injured.

The inhabitants of Korissia were moved by the suffering of the wounded. They offered all possible assistance to the survivors and hosted many of them in their houses while waiting for the rescue ships. Violet Jessop approached one of the wounded. "An elderly man, in an RAMC uniform with a row of ribbons on his breast, lay motionless on the ground. Part of his thigh was gone and one foot missing; the grey-green hue of his face contrasted with his fine physique. I took his hand and looked at him. After a long time, he opened his eyes and said; 'I'm dying'. There seemed nothing to disprove him yet I involuntarily replied; 'No, you are not going to die, because I've just been praying for you to live'. He gave me a beautiful smile ... That man lived and sang jolly songs for us on Christmas Day."

Scourge and Heroic had no deck space for more survivors, and they left for Piraeus signalling the presence of those left at Korissia. HMS Foxhound arrived at 11:45 and, after sweeping the area, anchored in the small port at 13:00 to offer medical assistance and take onboard the remaining survivors. At 14:00 the light cruiser HMS Foresight arrived. Foxhound departed for Piraeus at 14:15 while Foresight remained to arrange the burial on Kea of RAMC Sergeant William Sharpe, who had died of his injuries. Another two men died on the Heroic and one on the French tug Goliath. The three were buried with military honours in the British cemetery at Piraeus. The last fatality was G. Honeycott, who died at the Russian Hospital at Piraeus shortly after the funerals.

In total, 1,035 people survived the sinking. Thirty men lost their lives in the disaster but only five were buried. The others were left in the water, and their memory is honoured in memorials in Thessaloniki and London. Another 38 men were injured (18 crew, 20 RAMC).[21] The ship carried no patients. Survivors were hosted in the warships that were anchored at the port of Piraeus. However, the nurses and the officers were hosted in separate hotels at Phaleron. Many Greek citizens and officials attended the funerals.

In November 2006, Britannic researcher Michail Michailakis discovered that one of the 45 unidentified graves in the New British Cemetery on the island of Syros contained the remains of a soldier collected from the church of Ag. Trias at Livadi (the old name of Korissia). The information was passed to maritime historian Simon Mills, who came in contact with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Further research established that this soldier was a Britannic casualty and his remains had been registered in October 1919 as belonging to a certain "Corporal Stevens". When the remains were moved to the new cemetery at Syros (June 1921) it was found that there was no record relating this name with the loss of the ship, and the grave was registered as unidentified. Mills provided evidence that this man could be Sergeant William Sharpe, and the case was considered by the Service Personnel and Veterans Agency. Since the cause of the mistake could not be established with certainty, it was decided to have the grave marked with a new headstone bearing the inscription "Believed to be Sergeant William Sharpe". The new headstone was placed in 2009, and the CWGC has updated its database.[22] Sharpe is commemorated on the Mikra Memorial.[23]

Wreck

The wreck of HMHS Britannic is at 37°42′05″N 24°17′02″E / 37.70139°N 24.28389°E in about 400 feet (122 m) of water. It was first discovered and explored by Jacques Cousteau in 1975.[24] In 1976, he expressed the opinion that the ship had been sunk by a single torpedo, basing this opinion on the damage to her plates.[25] The giant liner lies on her starboard side hiding the zone of impact with the mine. There is a huge hole just beneath the forward well deck. The bow is attached to the rest of the hull only by some pieces of the B-deck. This is the result of the massive explosion that destroyed the entire part of the keel between bulkheads two and three and of the force of impact with the seabed. The bow is heavily deformed as the ship hit the seabed before the total length of the 882 ft 9 in (269 m) liner was completely submerged, as she sank in a depth of only 400 feet (120 m) of water. Despite this, the crew's quarters in the forecastle were found to be in good shape with many details still visible. The holds were found empty. The forecastle machinery and the two cargo cranes in the forward well deck are still there and are well preserved. The foremast is bent and lies on the sea floor near the wreck with the crow's nest still attached on it. The bell was not found. Funnel #1 was found a few metres from the Boat Deck. The other three funnels were found in the debris field (located off the stern). The wreck of Britannic is in excellent condition, and the only signs of deterioration are the children's playroom and some of the captain's quarters, but the rest of the ship is in outstanding shape. The wreck lies in shallow enough water that scuba divers trained in technical diving can explore it, but it is listed as a British war grave and any expedition must be approved by both the British and Greek governments.

In mid-1995, in an expedition filmed by NOVA, Dr Robert Ballard, best known for discovering the wrecks of RMS Titanic and the German battleship Bismarck, visited the wreck, using advanced side-scan sonar. Images were obtained from remotely controlled vehicles, but the wreck was not penetrated. Ballard found all the ship's funnels in surprisingly good condition. Attempts to find mine anchors failed.

In August 1996, the wreck of HMHS Britannic was bought by maritime historian Simon Mills, who has written two books about the ship: Britannic-The Last Titan, and Hostage To Fortune. When Mills was asked if he had all the money and support needed, what would his ideal vision be for the wreck of Britannic, he replied; "That's simple—to leave it as it is!"

In November 1997, an international team of divers led by Kevin Gurr used open-circuit trimix diving techniques to visit and film the wreck in the newly available DV digital video format.

In September 1998, another team of divers made an expedition to the wreck.[26] Using diver propulsion vehicles, the team made more man-dives to the wreck and produced more images than ever before, including video of four telegraphs, a helm and a telemotor on the captain's bridge.[27] John Chatterton became the first diver to visit Britannic using a closed-circuit rebreather, but his efforts to penetrate the firemen's tunnel using a rebreather were hampered by the poor reliability. The expedition was regarded as one of the biggest wreck diving projects ever undertaken. Time magazine published images shot in the expedition.

In 1999, GUE, divers acclimated to cave diving and ocean discovery, led the first dive expedition to include extensive penetration into Britannic. Video of the expedition was broadcast by National Geographic, BBC, the History Channel, and the Discovery Channel.[28]

In September 2003, an expedition led by Carl Spencer dived into the wreck. This was the first expedition to dive Britannic where all the bottom divers were using closed circuit rebreathers (CCR). Diver Rich Stevenson found that several watertight doors were open. It has been suggested that this was because the mine strike coincided with the change of watches. Alternatively, the explosion may have distorted the doorframes. A number of mine anchors were located off the wreck by sonar expert Bill Smith, confirming the German records of U-73 that Britannic was sunk by a single mine and the damage was compounded by open portholes and watertight doors. Spencer's expedition was broadcast extensively across the world for many years by National Geographic and the UK's Channel 5. Also in the expedition was microbiologist Dr Lori Johnston, who placed samples on Britannic to look at the colonies of iron-eating bacteria on the wreck, which are responsible for the rusticles growing on Titanic. The results showed that even after 87 years on the bottom of the Kea Channel, Britannic is in much better condition than Titanic because the bacteria on her hull have too much competition and are actually helping protect the wreck by turning it into a man-made reef.

In 2006, an expedition, funded and filmed by the History Channel, brought together fourteen skilled divers to help determine what caused the quick sinking of Britannic. After preparation the crew dived on the wreck site on 17 September. Time was cut short when silt was kicked up, causing zero visibility conditions, and the two divers narrowly escaped with their lives. One last dive was to be attempted on Britannic's boiler room, but it was discovered that photographing this far inside the wreck would lead to violating a permit issued by the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, a department within the Greek Ministry of Culture. Partly because of a barrier in languages, a last minute plea was turned down by the department. The expedition was unable to determine the cause of the rapid sinking, but hours of footage were filmed and important data was documented. Underwater Antiquities later recognised the importance of this mission and has since extended an invitation to revisit the wreck under less stringent rules. On this expedition, divers found a bulb shape in her expansion joint. This proved that her design was changed following the loss of Titanic.

On 29 May 2009, Carl Spencer, drawn back to his third underwater filming mission of Britannic, died in Greece due to equipment difficulties while filming the wreck for National Geographic.[29]

In 2012, on an expedition organised by Alexander Sotiriou and Paul Lijnen, divers using rebreathers successfully installed and recovered scientific equipment used for environmental purposes, to determine how fast bacteria are eating Britannic's iron compared to Titanic.[30]

Pipe organ

A Welte Philharmonic Organ was originally planned to be installed on board Britannic but because of the outbreak of war, the instrument never made its way over to Belfast.

In the restoration of a Welte organ, now in the Museum für Musikautomaten in Seewen, Switzerland, the restorers detected in April 2007 that the main parts of the instrument were signed by the German organ builders with "Britanik".[31] A photo of a drawing in a company prospectus, found in the Welte-legacy in the Augustiner Museum in Freiburg, proved that this was the organ intended for Britannic.[32]

Film adaptation

The sinking of the ship was dramatised in a 2000 film called Britannic that featured Edward Atterton, Amanda Ryan and Jacqueline Bisset. The film took several liberties with the events aboard the ship, depicting the sinking as being caused by an onboard saboteur rather than a naval mine.[33]

Postcards

| Postcards of Britannic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

References

- ↑ "HMHS Britannic (1914) Builder Data". MaritimeQuest. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

- 1 2 Bonsall, Thomas E. (1987). "8". Titanic. Baltimore, Maryland: Bookman Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8317-8774-5.

- ↑ "Design fault may have doomed Titanic before it sailed". The Age. 13 June 2007.

- ↑ "HMHS Britannic". ocean-liners.com. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ↑ Bonner, Kit; Bonner, Carolyn (2003). Great Ship Disasters. MBI Publishing Company. p. 60. ISBN 0-7603-1336-9.

- ↑ "White Star Line". 20thcenturyliners.com. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ Joshua Milford: What happened to Gigantic? Website viewed 9 June 2014

- 1 2 Mark Chirnside: Gigantic Dossier Website viewed 1 May 2012

- ↑ Paul Lee's website article on the Gigantic name.

- ↑ Launch footage and Funnel fitting British Pathe, accessed 18/02/2013

- ↑ http://hmhsbritannic.weebly.com/sinking.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chirnside 2011, p. 260.

- 1 2 Chirnside 2011, p. 259.

- ↑ Chirnside 2011, p. 261.

- ↑ "PBS Online – Lost Liners – Britannic". PBS. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ Chirnside 2011, p. 262.

- ↑ Lord 2005, p. 149.

- 1 2 Chirnside 2011, p. 266.

- ↑ Lord 2005, p. 103.

- ↑ Brewster & Coulter 1998, pp. 45 and 62.

- ↑ http://hmhsbritannic.weebly.com/crew-lists.html

- ↑ Mills, Simon (2009). "The Odyssey of Sergeant William Sharpe". Titanic Commutator (Titanic Historical Society) 33 (186).

- ↑ "CWGC Record for Sharpe". CWGC.

- ↑ "Search For The Britannic (1977)". YouTube. 2011-02-03. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ↑ "British Red Cross ship hit by torpedo" The Times (London). Tuesday, 23 November 1976. (59868), col F, p. 8.

- ↑ Hope, Nicholas (1998). "How We Dived The Britannic", Bubblevision.com. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ↑ Hope, Nicholas (1998). "HMHS Britannic Video", Bubblevision.com. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ↑ "HMHS Britannic". Ocean Discovery. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- ↑ Pidd, Helen (25 May 2009). "Tributes paid to diver Carl Spencer, killed filming Titanic sister ship". 25 May 2009 (Guardian). Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ "Project Britannic". divernet.com. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Christoph E. Hänggi: Die Britannic-Orgel im Museum für Musikautomaten Seewen So. Festschrift zur Einweihung der Welte-Philharmonie-Orgel; Sammlung Heinrich Weiss-Stauffacher. Hrsg.: Museum für Musikautomaten Seewen SO. Seewen: Museum für Musikautomaten, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.davidrumsey.ch/Britannic_discovered.pdf Sunken Ocean-Liner Britannic’s pipe organ found. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- ↑ "Britannic (2000) (TV)". Imdb.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

Bibliography

- Brewster, Hugh; Coulter, Laurie (1998). 8821⁄2 Amazing Answers to your Questions about the Titanic. Madison Press Book. ISBN 978-0-590-18730-5.

- Chirnside, Mark (2011) [2004]. The Olympic-Class Ships. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2868-0.

- Lord, Walter (2005) [1955]. A Night to Remember. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-8050-7764-3.

Further reading

- Mills, Simon (1992). H.M.H.S. "Britannic": Last Titan. Dorset: Waterfront Publications. ISBN 0946184712.

- Mills, Simon (2002). Hostage to Fortune: the dramatic story of the last Olympian, HMHS Britannic. Chesham, England: Wordsmith. ISBN 1899493034.

- Layton, J. Kent (2013). The Edwardian Superliners: a trio of trios. ISBN 9781445614380.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to RMS Britannic. |

- Newsreel footage of the launching of HMHS Britannic, 1914

- Maritimequest HMHS Britannic Photo Gallery

- Britannic Home at Atlantic Liners

- NOVA Online-Titanic's Lost Sister (Companion website to the PBS special Titanic's Lost Sister)

- Hospital Ship Britannic

- About the origins of the Britannic Organ

- Carl Spencer – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Images of HMHS Britannic at the English Heritage Archive

- HMHS Britannic at Titanic and Co.

- Pathé News gallery on the Olympic class

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||

Coordinates: 37°42′05″N 24°17′02″E / 37.70139°N 24.28389°E