High-intensity focused ultrasound

High intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU, or sometimes MRgFUS for magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound) is a medical procedure that applies high intensity focused ultrasound energy to locally heat and destroy diseased or damaged tissue through ablation.

HIFU is a hyperthermia therapy, a class of clinical therapies that use temperature to treat diseases. HIFU is also one modality of therapeutic ultrasound, involving minimally-invasive or non-invasive methods to direct acoustic energy into the body. In addition to HIFU, other modalities include ultrasound-assisted drug delivery, ultrasound hemostasis, ultrasound lithotripsy, and ultrasound-assisted thrombolysis.

Clinical HIFU procedures are typically performed in conjunction with an imaging procedure to enable treatment planning and targeting before applying a therapeutic or ablative levels of ultrasound energy. When Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is used for guidance, the technique is sometimes called Magnetic Resonance guided Focused Ultrasound, often shortened to MRgFUS or MRgHIFU.

Currently, HIFU is an approved therapeutic procedure to treat uterine fibroids in Asia, Australia, Canada, Europe, Israel and the United States. HIFU is approved for use in Bulgaria, China, Hong Kong, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Poland, Russia, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom. Research for other indications is actively underway, including clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of HIFU for the treatment of cancers of the brain, breast, liver, bone, prostate, as well as soft tissue tumors. Non-image guided HIFU devices may be marketed for cosmetic purposes (typically for body fat reduction) in some jurisdictions.

Medical uses

Therapeutic applications use ultrasound to bring heat or agitation into the body; much higher energies are used than in diagnostic ultrasound. In many cases the frequencies used are different.

- Ultrasound sources may be used to generate regional heating and mechanical changes in biological tissue, e.g. in occupational therapy, physical therapy and cancer treatment. However the use of ultrasound in the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions has fallen out of favor.[1][2]

- Focused ultrasound may be used to generate highly localized heating to treat cysts and tumors (benign or malignant), This is known as Magnetic Resonance guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS) or High Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU). These procedures generally use lower frequencies than medical diagnostic ultrasound (from 0.250 to 2 MHz), but significantly higher energies. HIFU treatment is often guided by MRI.

- Focused ultrasound may be used to break up kidney stones by lithotripsy.

- Ultrasound may be used for cataract treatment by phacoemulsification.

- Low-intensity ultrasound has been found to have physiological effects such as ability to stimulate bone-growth, and potential to temporarily disrupt the blood–brain barrier for drug delivery.[3]

- Procoagulant at 5–12 MHz

Uterine fibroids

Development of this therapy significantly broadened the range of treatment options for patients suffering from uterine fibroids. HIFU treatment for uterine fibroids was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2004.[4] This is a non-invasive treatment option for patients suffering from symptomatic fibroids. Most patients benefit from HIFU and symptomatic relief is sustained for two plus years. Up to 16-20% of patients will require additional treatment.[5]

Other benign tumors

Echopulse was the first HIFU device to receive CE marking in 2007 for benign thyroid nodules and hypertrophic parathyroid glands ablation and in 2012 for breast fibroadenoma ablation. The first echotherapy treatments on neck were performed in 2004 and in 2011 for breast fibroadenomas. Echopulse applications are developed by Theraclion, a spin-off from EDAP, that conceived and commercialized the Ablatherm device.

Functional neurosurgery

Transcranial magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound (tcMRgFUS surgery) is a promising technology for the non-invasive treatment of various brain disorders. It has been studied for essential tremor,[6] neuropathic pain.[7]

Prostate cancer

HIFU is being studied in men with prostate cancer.[8] In October 2015 the FDA authorized a HIFU device for the ablation of prostate tissue. [9]

The treatment is administered through a trans-rectal probe and uses heat developed by focusing ultrasound waves into localized prostate tumors to kill cancerous cells. Promising results have been reported in people with prostate cancer. These treatments are performed under ultrasound imaging guidance, which allows for treatment planning and some minimal indication of the energy deposition. This is an outpatient procedure that usually lasts 1–3 hours.

The standard ultrasound treatment of prostate cancer ablates the entire prostate, including the prostatic urethra. The urethra has regenerative ability because it is derived from a different type of tissue (bladder squamous-type epithelium) rather than prostatic tissue (glandular, fibrotic and muscular). While the urethra is an important anatomical structure, the sphincter and bladder neck are more important to maintaining the urinary function. During focused ultrasound treatment the sphincter and bladder neck are identified and not ablated.[10]

Other cancers

HIFU has been successfully applied in treatment of cancer to destroy solid tumors of the bone, brain, breast, liver, pancreas, rectum, kidney, testes, prostate.[11][12][13][14]

HIFU has been found to have palliative effects. CE approval has been given for palliative treatment of bone metastasis.[15] Experimentally, a palliative effect was found in cases of advanced pancreatic cancer.[16]

HIFU may also be used to produce heating for other purposes than cell destruction. For example, HIFU and other devices may be used to activate temperature-sensitive liposomes filled with cancer drug "cargo", to release the drug in high concentrations only at focused tumor sites and when triggered to do so by the hyperthermia device (See Hyperthermia therapy).

Cosmetic medicine

HIFU devices have been cleared to treat subcutaneous adipose tissue for the purposes of body contouring (known colloquially, and incorrectly since there is no suction involved, as "non-invasive liposuction"). These devices are available in the US,[17][18] Canada, the EU, Australia, and certain countries in Asia. HIFU is also cleared, with lower energy levels, for eyebrow lifts.

Method of use

In HIFU therapy for destruction of diseased tissue, ultrasound beams are focused on a small region to be treated, and deposit significant energy at the focus, causing local temperature to rise to between 65° and 85 °C, destroying the diseased tissue by coagulative necrosis. Higher temperatures are usually avoided to prevent boiling of liquids inside the tissue. Each sonication of the beams theoretically treats a precisely defined portion of the targeted tissue, although in practice cold spots (caused by, among other things, blood perfusion in the tissue), beam distortion, and beam mis-registration are impediments to finely controlled treatments. The entire therapeutic target is treated by moving the applicator on its robotic arm in order to juxtapose multiple shots, according to a protocol designed by the physician. This technology can achieve precise ablation of diseased tissue, therefore is sometimes called HIFU surgery, or "non-invasive HIFU surgery". Anesthesia is not required, but is generally recommended.

Mechanism of action

As an acoustic wave propagates through the tissue, part of it is absorbed and converted to heat. With focused beams, a very small focus can be achieved deep in tissues (usually on the order of milimeters, with the beam having a characteristic "cigar" shape in the focal zone, where the beam is longer than it is wide along the transducer axis). Tissue damage occurs as a function of both the temperature to which the tissue is heated and how long the tissue is exposed to this heat level in a metric referred to as "thermal dose". By focusing at more than one place or by scanning the focus, a volume can be thermally ablated. At high enough acoustic intensities, cavitation (microbubbles forming and interacting with the ultrasound field) can occur. Microbubbles produced in the field oscillate and grow (due to factors including rectified diffusion), and can eventually implode (inertial or transient cavitation). During inertial cavitation, very high temperatures inside the bubbles occur, and the collapse is associated with a shock wave and jets that can mechanically damage tissue. Because the onset of cavitation and the resulting tissue damage can be unpredictable, it has generally been avoided in clinical applications.

Theory

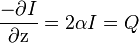

There are several ways to focus ultrasound—via a lens (for example, a polystyrene lens), a curved transducer, a phased array, or any combination of the three. This concentrates it into a small focal zone; it is similar in concept to focusing light through a magnifying glass. This can be determined using an exponential model of ultrasound attenuation. The ultrasound intensity profile is bounded by an exponentially decreasing function where the decrease in ultrasound is a function of distance traveled through tissue:

is the initial intensity of the beam,

is the initial intensity of the beam,  is the attenuation coefficient (in units of inverse length), and z is distance traveled through the attenuating medium (e.g. tissue).

is the attenuation coefficient (in units of inverse length), and z is distance traveled through the attenuating medium (e.g. tissue).

In this model,  [19] is a measure of the power density of the heat absorbed from the ultrasound field. Sometimes, SAR is also used to express the amount of heat absorbed by a specific medium, and is obtained by dividing Q by the tissue density. This demonstrates that tissue heating is proportional to intensity, and that intensity is inversely proportional to the area over which an ultrasound beam is spread—therefore, focusing the beam into a sharp point (i.e. increasing the beam intensity) creates a rapid temperature rise at the focus.

[19] is a measure of the power density of the heat absorbed from the ultrasound field. Sometimes, SAR is also used to express the amount of heat absorbed by a specific medium, and is obtained by dividing Q by the tissue density. This demonstrates that tissue heating is proportional to intensity, and that intensity is inversely proportional to the area over which an ultrasound beam is spread—therefore, focusing the beam into a sharp point (i.e. increasing the beam intensity) creates a rapid temperature rise at the focus.

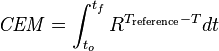

The amount of damage caused in the tissue can be modeled using Cumulative Equivalent Minutes (CEM). Several formulations of the CEM equation have been suggested over the years, but the equation currently in use for most research done in HIFU therapy comes from a 1984 paper by Dewey and Sapareto:[20]

with the integral being over the treatment time, R=0.5 for temperatures over 43 °C and 0.25 for temperatures between 43 °C and 37 °C, a reference temperature of 43 °C, and time in minutes. This formula is an empirical formula derived from experiments performed by Dewey and Sapareto by measuring the survival of cell cultures after exposure to heat.

Focusing

The ultrasound beam can be focused in these ways:

- Geometrically, for example with a lens or with a spherically curved transducer.

- Electronically, by adjusting the relative phases of elements in an array of transducers (a "phased array"). By dynamically adjusting the electronic signals to the elements of a phased array, the beam can be steered to different locations, and aberrations in the ultrasound beam due to tissue structures can be corrected.

Image-guided

High Intensity Focused Ultrasound requires a location tracking position to ensure safety and to verify that currents are going to the proper place. This allows lesion formation to be controlled where tissues are destroyed. Examples of this include x-ray, MRI, and Diagnostic Ultrasound. The most basic method of this is Visual monitoring. X-rays were the earliest form of guidance. MRI allows tissue contrast for localization of target volume, characterization of diffusion, perfusion, flow, and temperature, enabling detection of tissue damage. Diagnostic Ultrasound can indicate treatment progress by showing the area as hyper echoic images in real time during the scan.[21]

History

The first investigations of HIFU for non-invasive ablation were reported by Lynn et al. in the early 1940s. Extensive important early work was performed in the 1950s and 1960s by William Fry and Francis Fry at the University of Illinois and Carl Townsend, Howard White and George Gardner at the Interscience Research Institute of Champaign, Ill., culminating in clinical treatments of neurological disorders. In particular High Intensity ultrasound and ultrasound visualization was accomplished stereotaxically with a Cincinnati precision milling machine to perform accurate ablation of brain tumors. Until recently, clinical trials of HIFU for ablation were few (although significant work in hyperthermia was performed with ultrasonic heating), perhaps due to the complexity of the treatments and the difficulty of targeting the beam noninvasively. With recent advances in medical imaging and ultrasound technology, interest in HIFU ablation of tumors has increased.

The first commercial HIFU machine, called the Sonablate 200, was developed by the American company Focus Surgery, Inc. (Milipitas, CA) and launched in Europe in 1994 after receiving CE approval, bringing a first medical validation of the technology for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Comprehensive studies by practitioners at more than one site using the device demonstrated clinical efficacy for the destruction of prostatic tissue without loss of blood or long term side effects. Later studies on localized prostate cancer by Murat and colleagues at the Edouard Herriot Hospital in Lyon in 2006 showed that after treatment with the Ablatherm (EDAP TMS, Lyon, France), progression-free survival rates are very high for low- and intermediate- risk patients with recurrent prostate cancer (70% and 50% respectively)[22] HIFU treatment of prostate cancer is currently an approved therapy in Europe, Canada, South Korea, Australia, and elsewhere. Clinical trials for the Sonablate 500 in the United States are currently ongoing for prostate cancer patients and those who have experienced radiation failure.[23]

Use of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound was first cited and patented in 1992.[24][25] The technology was later transferred to InsighTec in Haifa Israel in 1998. The InsighTec ExAblate 2000 was the first MRgFUS system to obtain FDA market approval[4] in the United States.

Organizations

The International Society for Therapeutic Ultrasound (ISTU), founded in 2001, aims to promote clinical, academic and industrial advancement in therapeutic ultrasound.

References

- ↑ Robertson, VJ; Baker, KG (2001). "A review of therapeutic ultrasound: Effectiveness studies". Physical therapy 81 (7): 1339–50. PMID 11444997.

- ↑ Baker, KG; Robertson, VJ; Duck, FA (2001). "A review of therapeutic ultrasound: Biophysical effects". Physical therapy 81 (7): 1351–8. PMID 11444998.

- ↑ Hynynen, Kullervo; McDannold, Nathan; Sheikov, Nickolai A.; Jolesz, Ferenc A.; Vykhodtseva, Natalia (2005). "Local and reversible blood–brain barrier disruption by noninvasive focused ultrasound at frequencies suitable for trans-skull sonications". NeuroImage 24 (1): 12–20. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.046. PMID 15588592.

- 1 2 Food and Drug Administration Approval, ExAblate® 2000 System - P040003

- ↑ Stewart, Elizabeth A.; Gostout, Bobbie; Rabinovici, Jaron; Kim, Hyun S.; Regan, Lesley; Tempany, Clare M. C. (2007). "Sustained Relief of Leiomyoma Symptoms by Using Focused Ultrasound Surgery". Obstetrics & Gynecology 110 (2, Part 1): 279–87. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000275283.39475.f6. PMID 17666601.

- ↑ Elias, W. Jeffrey; Huss, Diane; Voss, Tiffini; Loomba, Johanna; Khaled, Mohamad; Zadicario, Eyal; Frysinger, Robert C.; Sperling, Scott A.; Wylie, Scott (2013-08-15). "A pilot study of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor". The New England Journal of Medicine 369 (7): 640–648. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300962. ISSN 1533-4406. PMID 23944301.

- ↑ Jeanmonod, Daniel; Werner, Beat; Morel, Anne; Michels, Lars; Zadicario, Eyal; Schiff, Gilat; Martin, Ernst (2012-01-01). "Transcranial magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound: noninvasive central lateral thalamotomy for chronic neuropathic pain". Neurosurgical Focus 32 (1): E1. doi:10.3171/2011.10.FOCUS11248. ISSN 1092-0684. PMID 22208894.

- ↑ Jácome-Pita, F; Sánchez-Salas, R; Barret, E; Amaruch, N; Gonzalez-Enguita, C; Cathelineau, X (2014). "Focal therapy in prostate cancer: the current situation.". Ecancermedicalscience 8: 435. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2014.435. PMID 24944577.

- ↑ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf15/DEN150011.pdf

- ↑ Dr. George Suarez, Medical Director Emeritus at International HIFU http://www.hifumedicalexpert.com/faq.html[]

- ↑ Ahrar, Kamran; Matin, Surena; Wood, Christopher G.; Wallace, Michael J.; Gupta, Sanjay; Madoff, David C.; Rao, Sujaya; Tannir, Nizar M.; Jonasch, Eric; Pisters, Louis L.; Rozner, Marc A.; Kennamer, Debra L.; Hicks, Marshall E. (2005). "Percutaneous Radiofrequency Ablation of Renal Tumors: Technique, Complications, and Outcomes". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 16 (5): 679–88. doi:10.1097/01.RVI.0000153589.10908.5F. PMID 15872323.

- ↑ Margulis, Vitaly; Matsumoto, Edward D.; Lindberg, Guy; Tunc, Lutfi; Taylor, Grant; Sagalowsky, Arthur I.; Cadeddu, Jeffrey A. (2004). "Acute histologic effects of temperature-based radiofrequency ablation on renal tumor pathologic interpretation". Urology 64 (4): 660–3. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.023. PMID 15491694.

- ↑ Mahnken, A. H.; Mahnken, J. (2004). "Perkutane Radiofrequenzablation von Nierentumoren" [Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of renal cell cancer]. Der Radiologe (in German) 44 (4): 358–63. doi:10.1007/s00117-004-1035-7. PMID 15048557.

- ↑ Wu, F; Wang, Z-B; Cao, Y-De; Chen, W-Z; Bai, J; Zou, J-Z; Zhu, H (2003). "A randomised clinical trial of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation for the treatment of patients with localised breast cancer". British Journal of Cancer 89 (12): 2227–33. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601411. PMC 2395272. PMID 14676799.

- ↑ "Philips Sonalleve receives CE Mark for MR-guided focused ultrasound ablation of metastatic bone cancer" (Press release). Philips Healthcare. April 20, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ↑ Wu, F.; Wang, Z.-B.; Zhu, H.; Chen, W.-Z.; Zou, J.-Z.; Bai, J.; Li, K.-Q.; Jin, C.-B.; Xie, F.-L.; Su, H.-B. (2005). "Feasibility of US-guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Treatment in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Initial Experience". Radiology 236 (3): 1034–40. doi:10.1148/radiol.2362041105. PMID 16055692.

- ↑ Application and FDA permission to market a device, 18 August 2011

- ↑ "510(k) Premarket Notification - K112626". 510(k) Premarket Notification Database. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved March 8, 2015. Premarket notification, device in classification "focused ultrasound for tissue heat or mechanical cellular disruption", classification description "Focused ultrasound stimulator system for aesthetic use"

- ↑ P Hariharan et al. (2007)

- ↑ Sapareto, SA; Dewey, WC (1984). "Thermal dose determination in cancer therapy". International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics 10 (6): 787–800. doi:10.1016/0360-3016(84)90379-1. PMID 6547421.

- ↑ Chan, Arthur H., Vaezy, Shahram, and Crum, Lawrence A. "High-intensity Focused Ultrasound." AccessScience. McGraw-Hill Education, 2003. Web. 4 May 2015.

- ↑ Gelet, A; Murat, François-Joseph; Poissonier, L (2007). "Recurrent Prostate Cancer After Radiotherapy – Salvage Treatment by High-intensity Focused Ultrasound". European Oncological Disease 1 (1): 60–2.

- ↑ USHIFU (2012). "Clinical Information about HIFU in the U.S.". Archived from the original on August 7, 2009.

- ↑ Hynynen, K.; Damianou, C.; Darkazanli, A.; Unger, E.; Levy, M.; Schenck, J. F. (1992). "On-line MRI monitored noninvasive ultrasound surgery". Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.1992.5760999. ISBN 0-7803-0785-2.

- ↑

External links

- Therapeutic Ultrasound at DMOZ

- FOCUS - Fast Object-oriented C++ Ultrasound Simulator Software for performing various ultrasound simulations with MATLAB

- Pine Street Foundation Review Article (Winter 2006)

- Despite Doubts, Cancer Therapy Draws Patients from The New York Times on 18

- Non-invasive Treatment for Pain Related to Bone Metastases- Using HIFU to treat pain related to bones metastases by UCSF Radiology and Biomedical Imaging

- Minimally Invasive Treatments for Fibroids in the Uterus - Using HIFU to treat uterine fibroids by UCSF Radiology and Biomedical Imaging