Henry Morton Stanley

| Henry Morton Stanley | |

|---|---|

Journalist and explorer | |

| Born |

John Rowlands 28 January 1841 Denbigh, Wales, UK |

| Died |

10 May 1904 (aged 63) London, England, UK |

| Awards | Vega Medal (1883) |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Henry Morton Stanley GCB (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh journalist and explorer famous for his exploration of central Africa and his search for missionary and explorer David Livingstone. Upon finding Livingstone, Stanley reportedly asked, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" Stanley is also known for his search for the source of the Nile, his work in and development of the Congo Basin region in association with King Leopold II of the Belgians, and for commanding the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. He was knighted in 1899.

Early life

Henry Stanley was born in 1841 as John Rowlands in Denbigh, Denbighshire, Wales. His mother Elizabeth Parry was 18 years old, and she abandoned him as a very young baby and cut off all communication. She had five more children by different men, only the youngest of whom was born in wedlock. Stanley never knew his father, who died within a few weeks of his birth;[1] there is some doubt as to his true parentage.[2] As his parents were unmarried, his birth certificate describes him as a bastard and the stigma of illegitimacy weighed heavily upon him all his life.[3]

The boy John was given his father's surname of Rowlands and brought up by his maternal grandfather Moses Parry, a once-prosperous butcher who was living in reduced circumstances. He cared for the boy until he died, when John was five. Rowlands stayed with families of cousins and nieces for a short time, but he was eventually sent to St Asaph Union Workhouse for the Poor. The overcrowding and lack of supervision resulted in his being frequently abused by older boys. Historian Robert Aldrich suggests that he was raped in 1847 by the headmaster of the workhouse.[4] When John was ten, his mother and two half-siblings stayed for a short while in this workhouse, but he did not recognize them; the master told him who they were.[5] He stayed until the age of 15. After completing an elementary education, he was employed as a pupil teacher in a National School.

New country, new name

Rowlands emigrated to the United States in 1859 at age 18, in search of a new life. He disembarked at New Orleans and, according to his own declarations, became friends quite by accident with a wealthy trader named Henry Hope Stanley. He saw Stanley sitting on a chair outside his store and asked him if he had any job openings. He did so in the British style: "Do you need a boy, sir?" As it happened, the childless man had indeed been wishing he had a son, and the inquiry led not only to a job, but to a close relationship between them.[6] Out of admiration, John took Stanley's name. Later, he wrote that his adoptive parent died two years after their meeting, but the elder Stanley did not die until 1878.[7] Young Stanley assumed a local accent and began to deny being a foreigner.

Stanley reluctantly joined[8] in the American Civil War, first enrolling in the Confederate Army's 6th Arkansas Infantry Regiment[9] and fighting in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.[10] After being taken prisoner, he was recruited at Camp Douglas, Illinois by its commander Col. James A. Mulligan as a "Galvanized Yankee." He joined the Union Army on 4 June 1862 but was discharged 18 days later due to severe illness.[11] Recovering, he served on several merchant ships before joining the US Navy in July 1864. He became a record keeper on board the Minnesota, which led him into freelance journalism. Stanley and a junior colleague jumped ship on 10 February 1865 at a port in New Hampshire, in search of greater adventures.[12] Stanley was possibly the only man to serve in the Confederate Army, the Union Army, and the Union Navy.[13]

Journalist

Following the Civil War, Stanley began a career as a journalist. As part of this new career, he organised an expedition to the Ottoman Empire that ended catastrophically when he was imprisoned. He eventually talked his way out of jail and received restitution for damaged expedition equipment.[14]

Finding Livingstone

.png)

Stanley travelled to Zanzibar in March 1871 and later claimed that he outfitted an expedition with the best of everything, requiring no fewer than 192 porters. [15] But in his first despatch to The New York Herald he stated that his expedition numbered only 111. This was in line with figures in his diaries. [16] Bennett had delayed sending Stanley the money he had promised, so Stanley had been obliged to borrow from the US Consul. [17] This 700-mile (1,100 km) expedition through the tropical forest became a nightmare. His thoroughbred stallion died within a few days after a bite from a tsetse fly, many of his carriers deserted, and the rest were decimated by tropical diseases. Some 21st century authors suggest that Stanley treated his indigenous porters quite well in contemporary terms, helping to refute his reputation for brutality.[18] But statements by contemporaries paint a very different picture, such as Sir Richard Francis Burton's claim that "Stanley shoots negroes as if they were monkeys".[19][20] Burton wrote this in a letter to General C. G. Gordon, who replied that killing in self-defence was permissible. "These things may be done," he wrote, "but not advertised." [21] On the subject of self-defence, Stanley wrote: "We went into the heart of Africa uninvited, therein lies our fault, but it was not so grave that our lives [when threatened] should be forfeited." [22]

Stanley found Livingstone on 10 November 1871 in Ujiji, near Lake Tanganyika in present-day Tanzania. He may have greeted him with the now-famous line, "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?" It may also have been a fabrication, as Stanley tore out of his diary the pages relating to the encounter. Neither man mentioned it in any of the letters they wrote at this time. [23] Livingstone's account of the encounter does not mention these words. The phrase is first quoted in a summary of Stanley's letters published by The New York Times on 2 July 1872.[24] Stanley biographer Tim Jeal argues that the explorer invented it afterwards as part of trying to raise his standing because of "insecurity about his background".[25]

The Herald's own first account of the meeting, published 1[26] July 1872, reports:

Preserving a calmness of exterior before the Arabs which was hard to simulate as he reached the group, Mr. Stanley said: – "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?" A smile lit up the features of the pale white man as he answered: "Yes, and I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you."[27][28]

Stanley joined Livingstone in exploring the region, establishing the fact that there was no connection between Lake Tanganyika and the River Nile. On his return, he wrote a book about his experiences: How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa.[29]

Researching the Congo River

In 1874, the New York Herald in partnership with Britain's Daily Telegraph financed Stanley on another expedition to the African continent. His objective was to complete the exploration and mapping of the central African lakes and rivers, in the process circumnavigating lakes Victoria and Tanganyika and locating the source of the Nile. A related mission was to solve another great mystery by tracing the course of the Congo River to the sea. The difficulty of this expedition is hard to overstate. Stanley used sectional boats and dug-out canoes to pass the great cataracts that separated the Congo into distinct tracts. The boats had to be taken apart and transported around the rapids before being rebuilt to travel on the next section of river. He reached the Portuguese outpost of Boma, around 100 km from the mouth of the Congo River, after 999 days on 9 August 1877. Muster lists and Stanley's diary (12 Nov 1874) show that he started with 228 people [30] and reached Boma with 114 survivors, and he was the only European left out of three. In Stanley's Through the Dark Continent (1878) (which coined the term "Dark Continent" for Africa), as if unaware that exaggerating his numbers diminished his achievement, Stanley stated that his expedition had numbered 356 altogether. [31] He wrote about his trials with similar exaggerations in his book Through the Dark Continent.[32] Stanley often recorded the great debt he owed to his leading African porters. His success, he wrote, was "all due to the pluck and intrinsic goodness of 20 men ... take the 20 out and I could not have proceeded beyond a few days journey". [33]

Claiming the Congo for the Belgian king

Stanley was approached by King Leopold II of the Belgians, the ambitious Belgian monarch who had organized a private holding company in 1876 disguised as an international scientific and philanthropic association, which he called the International African Association. The King spoke of his intentions to introduce Western civilization and bring religion to that part of Africa, but did not mention the fact that he wanted to claim the lands. At the end of his life, the King was embittered by the growing perception that his establishment of a Congo Free State was mitigated by its unscrupulous government. In addition, the spread of sleeping sickness across central Africa is attributed to the movements of Stanley's enormous baggage train[34] and the Emin Pasha relief expedition.

Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

In 1886, Stanley led the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition to "rescue" Emin Pasha, the governor of Equatoria in the southern Sudan. King Leopold II demanded that Stanley take the longer route via the Congo River, hoping to acquire more territory and perhaps even Equatoria. After immense hardships and great loss of life, Stanley met Emin in 1888, charted the Ruwenzori Range and Lake Edward, and emerged from the interior with Emin and his surviving followers at the end of 1890.[35] But this expedition tarnished Stanley's name because of the conduct of the other Europeans — British gentlemen and army officers. Army Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot was shot by a carrier after behaving with extreme cruelty. James Sligo Jameson, heir to Irish whiskey manufacturer Jameson's, bought an 11-year-old girl and offered her to cannibals to document and sketch how she was cooked and eaten. Stanley found out only when Jameson had died of fever.[3]

Later years

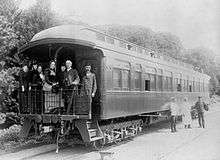

On his return to Europe, Stanley married Welsh artist Dorothy Tennant and they adopted a child named Denzil. Denzil donated some 300 items to the Stanley archives at the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium in 1954, and died in 1959.[36] Stanley entered Parliament as a Liberal Unionist member for Lambeth North, serving from 1895 to 1900. He became Sir Henry Morton Stanley when he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the 1899 Birthday Honours, in recognition of his service to the British Empire in Africa.[37]

He died in London on 10 May 1904. At his funeral, he was eulogised by Daniel P. Virmar. His grave is in the churchyard of St. Michael's Church in Pirbright, Surrey, marked by a large piece of granite inscribed with the words "Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841–1904, Africa". Bula Matari translates as "Breaker of Rocks" or "Breakstones" in Kongo, and was Stanley's name among locals in Congo. It can be translated as a term of endearment for, as the leader of Leopold's expedition, he commonly worked with the labourers breaking rocks with which they built the first modern road along the Congo River.[38] It can also be translated in far less flattering terms. Adam Hochschild suggested that Stanley understood it as a heroic epithet, but his Congolese companions understood it in a mocking and pejorative tone.[39]

Charges of cruelty

Stanley acknowledged that "[m]any people have called me hard."[40] In Through the Dark Continent, he wrote that "the savage only respects force, power, boldness, and decision."[32] Yet in How I Found Livingstone he wrote that he was "prepared to admit any black man possessing the attributes of true manhood, or any good qualities ... to a brotherhood with myself." [41] But the legacy of death and destruction in the Congo region, and the fact that Stanley had worked for King Leopold II of Belgium, is considered by some to have made him an inspiration for Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness.[42] But this claim, however, rests on the mistaken assumption that Conrad had spent his six months as a steamship captain on the Congo when Stanley was there (1879-1884) rather than in 1890, as was the case, five years after Stanley had been recalled to Europe and had ceased to be King Leopold's chief agent in Africa. By 1890 forced labour was being used to coerce Africans into collecting rubber. But when Stanley had been there, the inner tube for bicycle tyres had not yet been invented and there had been little demand for rubber. [43]

Stanley did receive some vilification for the way that he conducted his expeditions, and he is still vilified today by some. More specifically, there were charges of indiscriminate cruelty against Africans. Some of the modern charges are explained away as journalistic exaggerations, yet it is important to note that some of his contemporaries also brought the same charges, including many men who served under him or had first hand information. For instance, immediately after one of his expeditions in 1877, the Rev. J. P. Farler met with African porters who had been part of the expedition and wrote the following: "Stanley's followers give dreadful accounts to their friends of the killing of inoffensive natives, stealing their ivory and goods, selling their captives, and so on. I do think a commission ought to inquire into these charges, because if they are true, it will do untold harm to the great cause of emancipating Africa. I have lived three years in Africa, I have travelled through and came in contact with many different tribes, even tribes that the Arabs report to be fierce, but I have invariably found them kind and inoffensive to me, a little selfish perhaps but fierce only when they are outraged. I cannot understand all the killing that Stanley has found necessary."[44] Other missionaries, such as the Baptist T.J. Comber, wrote differently about Stanley saying that, "by constant daily exercise of his tact and influence over the people ... Mr Stanley has succeeded in planting his station at Stanley Pool without a fight", despite being faced by Africans 'who are very fond of fighting and can muster 3000 guns." [45]

Modern media

In 1939, a popular film was released called Stanley and Livingstone, with Spencer Tracy as Stanley and Cedric Hardwicke as Livingstone.

The 1949 comedy film Africa Screams is the story of a dimwitted clerk named Stanley Livington (played by Lou Costello), who is mistaken for a famous African explorer and recruited to lead a treasure hunt. The character's name appears to be a play on Stanley and Livingstone, but with a few crucial letters omitted from the surname; it is unknown whether this results from a typist's error or a deliberate obfuscation.

Stanley appears as a character in Simon Gray's 1978 play The Rear Column, which tells the story of the men left behind to wait for Tippu Tib while Stanley went on to relieve Emin Pasha.

An NES game based on his life was released in 1992 called "Stanley: The Search for Dr. Livingston".[46]

In 1997, the made-for-television film Forbidden Territory: Stanley's Search for Livingstone was produced by National Geographic. Stanley was portrayed by Aidan Quinn and Livingstone was portrayed by Nigel Hawthorne.

His great grandson Richard Stanley is a South African filmmaker and directs documentaries.[47]

A hospital in St. Asaph, northern Wales is named after Stanley in honour of his birth in the area. It was formerly the workhouse in which he spent much of his early life. Memorials to H M Stanley have recently been erected in St Asaph and in Denbigh (a statue of H M Stanley with an outstretched hand).

In 1971, the BBC produced a six-part dramatised documentary series entitled Search for the Nile. Much of the series was shot on location, with Stanley played by Keith Buckley.[48]

In 2004, Welsh journalist Tim Butcher wrote his book "Blood River: A Journey Into Africa's Broken Heart", following Stanley's journey through the Congo.

The 2009 History Channel series Expedition Africa documents a group of explorers attempting to traverse the route of Stanley's expedition in search of Livingstone.

In 2015, Oscar Hijuelos wrote a novel, "Twain & Stanley Enter Paradise", which retells the story of Stanley's life through a focus on his friendship with Mark Twain.

Taxa named in honour

Taxa named in honour of Henry Morton Stanley include:

- freshwater snail Gabbiella stanleyi (E. A. Smith, 1877)[49]

- freshwater snail genus Stanleya Bourguignat, 1885[50]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Stanley, Henry M. (ed. Dorothy Stanley) (1909) The Autobiography of Henry M. Stanley, Houghton Mifflin Company, New York

- ↑ "Henry Morton Stanley", Dictionary of Welsh Biography

- 1 2 Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley – The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 17–19, 356. ISBN 0-571-22102-5.

- ↑ Robert Aldrich. Colonialism and Homosexuality. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2011). Explorers of the Nile. London: Faber and Faber. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-571-24976-3.

- ↑ "The Making of an American Lion", American Heritage, Vol. 25, No. 2 (February 1974).

- ↑ Edgerton, Robert T. (2002). The Troubled Heart of Africa. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-312-30486-2.

- ↑ Gallop p 50

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/grant-stanley/

- ↑ Arnold, James (1998). Shiloh 1862. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-606-4. p. 32

- ↑ Gallop, p. 61

- ↑ Gallop, pp 63–65

- ↑ Brown, Dee (1963). The Galvanized Yankees, University of Illinois Press (Urbana); ISBN 978-0-8032-6075-7, p. 58.

- ↑ Gallop, pp 71–73

- ↑ Stanley, Henry M. (1872). How I Found Livingstone in Central Africa. Sampson Low. p. 68.

- ↑ Bennett, Norman R. (1970). Stanley's Despatches to the New York Herald 1871-1872, 1874-1877. Boston University Press. p. 13.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim. Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. Faber and Faber. pp. 93–94.

- ↑ John Carey (18 March 2007). "A good man in Africa?". The Sunday Times (London). Archived from the original on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ↑ Lefort, Rebecca (25 July 2010). "Row over statue of 'cruel' explorer Henry Morton Stanley". The Daily Telegraph (London).

- ↑ Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-395-75924-2. See also Bierman, John. Dark Safari: The Life behind the Legend of Henry Morton Stanley.

- ↑ Wilkins, W. H. (1897). Romance of Isabel Lady Burton. pp. 661 volume 2.

- ↑ H. M. Stanley Congo Diaries 15.10.1880 Royal Museum of Central Africa

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-22102-5.

- ↑ "THE SEARCH FOR LIVINGSTON: Progress of the Englishman Stanley – Fierce Encounter with Arabs – Arrival at the Coast – The Great Explorer Remains Two Years More in Africa", London, 1 July New York Times, 2 July 1872. Accessed 19 May 2008.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-22102-5. p. 117

- ↑ NY Herald July 1, 1872

- ↑ "David Livingstone letter deciphered at last. Four-page missive composed at the lowest point in his professional life". Associated Press. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ↑ Livingstone's Letter from Bambarre http://emelibrary.org/livingstoneletter (accessed 4 July 2010)

- ↑ Stanley, Henry M. (19 February 2002). How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveres in Central Africa. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-41953-3.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. Faber and Faber. pp. 163, 511 note 21.

- ↑ Hall, Richard (1974). Stanley: An Adventurer Explored. Collins. p. 33.

- 1 2 Stanley, Henry M. (1988). Through the Dark Continent. Dover Publications. pp. 432 pages. ISBN 0-486-25667-7.

- ↑ Stanley to Edward King 2.10.1877 RMCA

- ↑ Alastair Compston (2008). "Editorial". Brain 131 (5): 1163–64. doi:10.1093/brain/awn070. PMID 18450785.

- ↑ (Turnbull, 1983)

- ↑ RMCA (2005) Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives

- ↑ The Edinburgh Gazette: no. 11101. p. 589. 13 June 1899. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim

- ↑ Hochschild (1998)

- ↑ See Stanley's introduction to Glave, E. J. (1892). In Savage Africa; or, Six Years of Adventure in Congo-Land. New York, NY: R. H. Russell & Son. Quote on p. 12.

- ↑ Stanley, Henry M. (1872). How I Found Livingstone in Central Africa. Sampson Low. p. 10.

- ↑ Sherry, Norman (1980). Conrad's Western World. Cambridge University Press. p. 340. ISBN 0-521-29808-3.

- ↑ Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley: The Imopossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. Faber and Faber. pp. 449, 452.

- ↑ Extract from a letter of the Rev J.P. Farler, Magila, Zanzibar, Dec 28 1877. FO 84/1527

- ↑ Letter from T.J.Comber to Mission Secretary Baynes 4.07.1882, Baptist Archive, Regent's Park College, Oxford.

- ↑ Stanley: The Search for Dr. Livingston

- ↑ Richard Stanley (I) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "The Search for the Nile: Find Livingstone". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ↑ Smith E. A. (1877). "On the shells of Lake Nyasa, and on a few marine species from Mozambique". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1877: 712–722. Page 717, Plate 75, figures 21–22.

- ↑ (French) Bourguignat J. R. (1885). Notice prodromique sur les mollusques terrestres et fluviatiles recueillis par M. Victor Giraud dans la region méridionale du lac Tanganika. page 11, 86–87.

References

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henry Morton Stanley |

- Gallop, Alan. (2004) Mr Stanley, I presume – the life and explorations of Henry Morton Stanley, Sutton

- Hall, Richard. (1974) Stanley. An Adventurer Explored, London.

- Stanley, Henry M. (ed. Dorothy Stanley) (1909, 1969) The Autobiography of Henry M. Stanley, New York.

Further reading

- Bierman, John: Dark Safari: The Life behind the Legend of Henry Morton Stanley. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990. ISBN 0-394-58342-6

- Dugard, Martin: Into Africa: The Epic Adventures of Stanley and Livingstone, 2003. ISBN 0-385-50451-9

- Hochschild, Adam: King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1998; Mariner Books, 1999 (pb). ISBN 0-618-00190-5 (pb)

- Hughes, Nathaniel, Jr. Sir Henry Morton Stanley, Confederate ISBN 0-8071-2587-3 reprint with introduction copyright 2000, from original, The Autobiography of Sir Henry Morton Stanley (1909)

- Jeal, Tim (2007). Stanley – The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-22102-5.

- Liebowitz, Daniel; Pearson, Charles: The Last Expedition: Stanley's Mad Journey Through the Congo, 2005. ISBN 0-393-05903-0

- Newman, James L. Imperial Footprints: Henry Morton Stanley's African Journeys, 2004. Washington, DC: Brassey's Inc.

- Pakenham, Thomas: The Scramble for Africa. Abacus History, 1991. ISBN 0-349-10449-2

- Petringa, Maria: Brazza, A Life for Africa, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- The British Medical Journal 1870–1871 editions have numerous reports of Stanley's progress in trying to track David Livingston.

- Simpson, J. 2007. Not Quite World's End A Traveller's Tales. pp. 291–293; 294–296. Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-43560-4

- Anonymous (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day. Illustrated by Frederick Waddy. London: Tinsley Brothers. pp. 124–5. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Morton Stanley. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henry Morton Stanley |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1900 Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography article about Henry Morton Stanley. |

- Stanley and Livingstone Original reports from The Times

- Works by Henry Morton Stanley at Project Gutenberg

- How I Found Livingstone at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Morton Stanley at Internet Archive

- Works by Henry Morton Stanley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- How I Found Livingstone, illustrated. From Internet Archive.

- In darkest Africa; or, The quest, rescue, and retreat of Emin, governor of Equatoria. Volume 1 (1890), illustrated. From Internet Archive.

- In darkest Africa; or, The quest, rescue, and retreat of Emin, governor of Equatoria. Volume 2 (1890), illustrated. From Internet Archive.

- Sir Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904), Explorer and journalist Sitter associated with 27 portraits

- Letters and maps associated with HM Stanley from Gathering the Jewels

- HM Stanley and Knife Crime

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Sir Henry Stanley

- Collected journalism of Henry Stanley at The Archive of American Journalism

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Francis Moses Coldwells |

Member of Parliament for Lambeth North 1895 – 1900 |

Succeeded by Frederick William Horner |

|