Gurjara-Pratihara

| Gurjara-Pratihara | |||||

| |||||

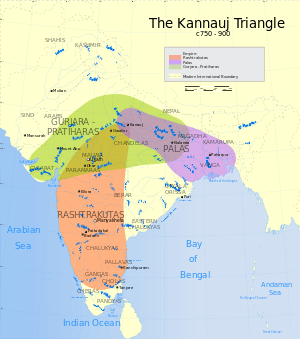

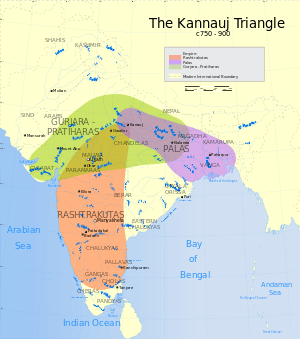

Extent of the Pratihara Empire shown in green | |||||

| Capital | Kannauj | ||||

| Languages | Sanskrit, Prakrit | ||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Historical era | Late Classical India | ||||

| • | Established | mid-7th century CE | |||

| • | Battle of Rajasthan | 738 CE | |||

| • | Conquest of Kannauj by Mahmud of Ghazni | 1008 CE | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1036 CE | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

The Gurjara-Pratihara Dynasty, also known as the Pratihara Empire, was an Indian imperial power that ruled much of Northern India from the mid-7th to the 11th century. It is named after its ruling dynasty, whose rulers were members of the Gurjara (Gurjar) and Pratihara tribes; who were followers of Hinduism. Some of their clans later came to be known as Rajputs. They ruled first at Ujjain and later at Kannauj.[1]

The Gurjara-Pratiharas were instrumental in containing Arab armies moving east of the Indus River.[2] Nagabhata I defeated the Arab army under Junaid and Tamin in the Battle of Rajasthan. Under Nagabhata II, the Gurjara-Pratiharas became the most powerful dynasty in northern India. Nagabhata II was succeeded by his son Ramabhadra, who ruled briefly, and was succeeded by his son Mihira Bhoja I. Under Bhoja and his successor Mahendrapala I, the Pratihara Empire reached its peak of prosperity and power. The extent of its territory rivaled that of the Gupta Empire, by the time of Mahendrapala, the empire reached west to the border of Sindh, east to Bengal, north to the Himalayas, and south past the Narmada.[3][4] The expansion once again triggered the power struggle for the control of the Indian Subcontinent, known as the Tripartite Struggle, with the Rashtrakuta Empire and Pala Empire. During this period, Imperial Pratihara took the title Maharajadhiraja of Āryāvarta (Great King of Kings of Northern India).

Gurjara-Pratihara are known for their sculptures, carved panels and open pavilion style temples. The greatest development of Gurjara-Pratihara style of temple building took place at Khajuraho (a UNESCO World Heritage Site).[5]

The power of the Pratiharas was weakened by dynastic strife. It was further diminished as a result of a great raid from the Deccan, led by the Rashtrakuta ruler Indra III, who about 916 sacked Kannauj. Under a succession of rather obscure rulers, the Pratiharas never regained their former influence. Their feudatories became more and more powerful, one by one throwing off their allegiance until by the end of the 10th century the Pratiharas controlled little more than the Gangetic Doab. Their last important king, Rajyapala, was driven from Kannauj by Mahmud of Ghazni in 1018.[4]

Etymology

"Gurjara-Pratihara" is a dynastic designation based on two terms, "Gurjara" and "Pratihara". The oldest form of this designation is "Gurjara-Pratiharanvayah", as mentioned in the Rajor inscription in reference to the 10th century Pratihara king Mathanadeva.[6] The modern designation "Gurjara-Pratihara" was coined during the British rule in India by British and Indian historians of the time, and ever since has become a standard name for this medieval north Indian empire.

The term "Gurjara" originally referred to a nomadic, pastoral people, believed to have been the predecessors of modern-day Rajput and Gurjar groups.[1] "Gurjara" is also known to have been used in a geographical sense to identify a kingdom in southern Rajasthan and northern Gujarat as well as its inhabitants. The oldest written record of this term can be found in the book Harsha Charita, written around 7th century AD.[7]

The second term "Pratihara" is the name of a clan or dynasty. The imperial records of the Pratihara dynasty derive this name from the epic hero Sri Lakshmana, who is believed to have been known as a Pratihara, because he was a "Guardian" of his brother Sri Rama's throne.[8] However, according to some modern scholars, a Pratihara ancestor served as a "minister of defense" (or Pratihara) in a Rasthrakutta court, and thats how the dynasty came to be known as Pratihara.[9]

Origin

The ethnicity of Gurjara-Pratiharas has been debated by scholars since the early 20th century. V. A. Smith, D. R. Bhandarkar, R. C. Majumdar and Baij Nath Puri have held that they were ethnic Gurjaras whereas G. H. Ojha and Dasharatha Sharma have maintained that they acquired the name by virtue of being rulers of the Gurjara country.[10] The rationale for postulating a Gurjara ethnicity is that the phrase Gurjāra-Pratihārānvayah occurs in the Rajor inscription of the Pratihara feudatory Mathanadeva in 959 CE (interpreted as the Pratihara clan of the Gurjaras). The rival kingdoms of Rashtrakutas and Palas refer to as Pratiharas as Gurjaresa and Gurjarendra (the Lord of Gurjaras).[11][12] On the other hand, the Pratiharas themselves never referred to themselves as Gurjaras.[12] Shanta Rani Sharma has also noted that an inscription of Gallaka in 795 CE states that Nagabhata I, the founder of the Imperial Pratihara dynasty, conquered the "invincible Gurjaras," which makes it unlikely that the Pratiharas were themselves Gurjaras.[13]

According to a legend given in later manuscripts of Prithviraj Raso, the Pratiharas were one of the Agnikula clans of Rajputs, deriving their origin from a sacrificial fire-pit (agnikunda) at Mount Abu.[14] This mythical story of Agnikula does not appear in the original version of Prithviraj Raso.[15]

The Pratihara dynasty is referred to as Gurjara Pratihārānvayah, i.e., Pratihara clan of the Gurjaras, in line 4 of the Rajor inscription (Alwar).[16][17] The historian Ramashankar Tripathi says that the inscription confirms the Gurjara origin of the Pratiharas. In line 12 of this inscription, occur words which have been translated as "together with all the neighbouring fields cultivated by the Gurjaras". Here, the cultivators themselves are clearly called Gurjaras and therefore it is reasonable to presume that, in line four too, the term bears a racial signification. The Rashtrakuta dynasty records, as well as the Arab writers like Abu Zaid and Al-Masudi (who allude their fights with the Juzr or Gurjara of the north), indicate the Gurjara origin of the Pratiharas. The Kannada poet Pampa expressly calls Mahipala Ghurjararaja. This epithet could hardly be applied to him, if the term Ghurjararaja bore a geographical sense denoting what after all was only a small portion of Mahipala's vast territories.[18] Tripathi believes that all these evidences point to the Gurjara ancestry of the Pratiharas.[19]

Dasharatha Sharma believed that the term Gurjara was applied to territory and concluded that, although some sections of the Pratiharas (e.g. the one to which Mathanadeva belonged) were Gurjaras by ethnicity, the imperial Pratiharas of Kannauj were not Gurjaras.[20] The Gurjara country is mentioned in Bana's Harshacharita (7th century CE). It is described in detail as a beautiful country in Udyotana Suri's Kuvalayamala (8th century CE, composed in Jalore), whose residents are also referred to as Gurjaras. Xuanzang (7th century CE) refers to the Gurjara country (Ku-che-lo) with its capital at Bhinmal (Pi-lo-mo-lo). The fourth book of Panchatantra contains the story of a rathakāra (charioteer) who went to a Gurjara village in the Gurjara country in search of camels. Al Baladhuri's chronicle of Al Junayd's expeditions (723-726 CE), the Navsari grant of Avanijanashraya Pulakesi (738-739 CE) and the Ragholi plate (8th century) refer to Gurjara as a country.[21][22] According to K. M. Munshi, the people residing in the Gurjaradesa, whenever they migrated to other parts of the country, were known as Gurjaras.[23] V. B. Mishra concludes that the expression Gurjara Pratihārānvayah may very reasonably be taken to mean the Pratihara family of the Gurjara country.[24]

Rulers

| Gurjara-Pratihara rulers (650–1036 AD) | |

| Nagabhata I | (730–760) |

| Kakkuka and Devaraja | (760–780) |

| Vatsaraja | (780–800) |

| Nagabhata II | (800–833) |

| Ramabhadra | (833–836) |

| Mihira Bhoja I | (836–885) |

| Mahendrapala I | (885–910) |

| Bhoja II | (910–913) |

| Mahipala I | (913–944) |

| Mahendrapala II | (944–948) |

| Devapala | (948–954) |

| Vinayakapala | (954–955) |

| Mahipala II | (955–956) |

| Vijayapala II | (956–960) |

| Rajapala | (960–1018) |

| Trilochanapala | (1018–1027) |

| Jasapala (Yashpala) | (1024–1036) |

Early rulers

Harichandra is said to have laid the foundation of this dynasty in the 6th century. He created a small kingdom at Bhinmal around 550 A.D. after the fall of the Gupta Empire. The Harichandra line of Gurjara-Pratiharas established the state of Marwar, based at Mandore near modern Jodhpur, which grew to dominate Rajasthan. The Pratihara rulers of Marwar also built the temple-city of Osian.

Expansion

Nagabhata I (730–756) extended his control east and south from Mandor, conquering Malwa as far as Gwalior and the port of Bharuch in Gujarat. He established his capital at Avanti in Malwa, and checked the expansion of the Arabs, who had established themselves in Sind. In this Battle of Rajasthan (738 CE) Nagabhata led a confedracy of Gurjara-Pratiharas to defeat the Muslim Arabs who had till then been pressing on victorious through West Asia and Iran. Nagabhata I was followed by two weak successors, who were in turn succeeded by Vatsraja (775–805).

Conquest of Kannauj and further expansion

The metropolis of Kannauj had suffered a power vacuum following the death of Harsha without an heir, which resulted in the disintegration of the Empire of Harsha. This space was eventually filled by Yashovarman around a century later but his position was dependent upon an alliance with Lalitaditya Muktapida. When Muktapida undermined Yashovarman, a tri-partite struggle for control of the city developed, involving the Pratiharas, whose territory was at that time to the west and north, the Palas of Bengal in the east and the Rashtrakutas, whose base lay at the south in the Deccan.[25][26] Vatsraja successfully challenged and defeated the Pala ruler Dharmapala and Dantidurga, the Rashtrakuta king, for control of Kannauj.

Around 786, the Rashtrakuta ruler Dhruva (c. 780–793) crossed the Narmada River into Malwa, and from there tried to capture Kannauj. Vatsraja was defeated by the Dhruva Dharavarsha of the Rashtrakuta dynasty around 800. Vatsraja was succeeded by Nagabhata II (805–833), who was initially defeated by the Rashtrakuta ruler Govinda III (793–814), but later recovered Malwa from the Rashtrakutas, conquered Kannauj and the Indo-Gangetic Plain as far as Bihar from the Palas, and again checked the Muslims in the west. He rebuilt the great Shiva temple at Somnath in Gujarat, which had been demolished in an Arab raid from Sindh. Kannauj became the center of the Gurjara-Pratihara state, which covered much of northern India during the peak of their power, c. 836–910.

Rambhadra (833-c. 836) briefly succeeded Nagabhata II. Mihira Bhoja I (c. 836–886) expanded the Pratihara dominions west to the border of Sind, east to Bengal, and south to the Narmada. His son, Mahenderpal I (890–910), expanded further eastwards in Magadha, Bengal, and Assam.

Decline

Bhoj II (910–912) was overthrown by Mahipala I (912–914). Several feudatories of the empire took advantage of the temporary weakness of the Gurjara-Pratiharas to declare their independence, notably the Paramaras of Malwa, the Chandelas of Bundelkhand, and the Kalachuris of Mahakoshal. The south Indian Emperor Indra III (c.914–928) of the Rashtrakuta dynasty briefly captured Kannauj in 916, and although the Pratiharas regained the city, their position continued to weaken in the 10th century, partly as a result of the drain of simultaneously fighting off Turkic attacks from the west, the attacks from the Rashtrakuta dynasty from the south and the Pala advances in the east. The Gurjara-Pratiharas lost control of Rajasthan to their feudatories, and the Chandelas captured the strategic fortress of Gwalior in central India, c. 950. By the end of the 10th century the Gurjara-Pratihara domains had dwindled to a small state centered on Kannauj.

Mahmud of Ghazni captured Kannauj in 1018, and the Pratihara ruler Rajapala fled. The Chandela ruler Ganda captured and killed Rajapala,[27]:21–22 placing Rajapala's son Trilochanpala on the throne as a proxy. Jasapala, the last Gurjara-Pratihara ruler of Kannauj, died in 1036.

Gurjara-Pratihara art

There are notable examples of architecture from the Gurjara-Pratihara era, including sculptures and carved panels.[28] Their temples, constructed in an open pavilion style, were particularly impressive at Khajuraho.[5]

Battle of Rajasthan

Junaid, the successor of Qasim, finally subdued the Hindu resistance within Sindh. Taking advantage of the conditions in Western India, which at that time was covered with several small states, Junaid led a large army into the region in early 738 CE. Dividing this force into two he plundered several cities in southern Rajasthan, western Malwa, and Gujarat.

Indian inscriptions confirm this invasion but record the Arab success only against the smaller states in Gujarat. They also record the defeat of the Arabs at two places. The southern army moving south into Gujarat was repulsed at Navsari by the south Indian Emperor Vikramaditya II of the Chalukya dynasty and Rashtrakutas. The army that went east, after sacking several places, reached Avanti whose ruler Nagabhata (Gurjara-Pratihara) trounced the invaders and forced them to flee. After his victory Nagabhata took advantage of the disturbed conditions to acquire control over the numerous small states up to the border of Sindh.

Junaid probably died from the wounds inflicted in the battle with the Gurjara-Pratihara. His successor Tamin organized a fresh army and attempted to avenge Junaid’s defeat towards the close of the year 738 CE. But this time Nagabhata], with his Chauhan and Guhilot feudatories, met the Muslim army before it could leave the borders of Sindh. The battle resulted in the complete rout of the Arabs who fled broken into Sindh with the Gurjara-Pratihara close behind them.

The Arabs crossed over to the other side of the Indus River, abandoning all their lands to the victorious Hindus. The local chieftains took advantage of these conditions to re-establish their independence. Subsequently the Arabs constructed the city of Mansurah on the other side of the wide and deep Indus, which was safe from attack. This became their new capital in Sindh. Thus began the reign of the imperial Gurjara-Pratiharas.

In the Gwalior inscription, it is recorded that Gurjara-Pratihara emperor Nagabhata "crushed the large army of the powerful Mlechcha king." This large army consisted of cavalry, infantry, siege artillery, and probably a force of camels. Since Tamin was a new governor he had a force of Syrian cavalry from Damascus, local Arab contingents, converted Hindus of Sindh, and foreign mercenaries like the Turkics. All together the invading army may have had anywhere between 10–15,000 cavalry, 5000 infantry, and 2000 camels.

The Arab chronicler Sulaiman describes the army of the Pratiharas as it stood in 851 CE, "The ruler of Gurjars maintains numerous forces and no other Indian prince has so fine a cavalry. He is unfriendly to the Arabs, still he acknowledges that the king of the Arabs is the greatest of rulers. Among the princes of India there is no greater foe of the Islamic faith than he. He has got riches, and his camels and horses are numerous."[29]

Legacy

Historians of India, since the days of Elphinstone, have wondered at the slow progress of Muslim invaders in India, as compared with their rapid advance in other parts of the world. The Arabs possibly only stationed small invasions independent of the Caliph. Arguments of doubtful validity have often been put forward to explain this unique phenomenon. Currently it is believed that it was the power of the Gurjara-Pratihara army that effectively barred the progress of the Muslims beyond the confines of Sindh, their first conquest for nearly three hundred years. In the light of later events this might be regarded as the "Chief contribution of the Gurjara Pratiharas to the history of India".[30]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gurjara-Pratihara. |

- 1 2 Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The Ancient Past. A History of the Indian-Subcontinent from 7000 BC to AD 1200. New York: Routledge. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-203-08850-0.

Madhyadesha became the ambition of two particular clans among a tribal people in Rajasthan, known as Gurjara and Pratihara. They were both part of a larger federation of tribes, some of which later came to be known as the Rajputs

- ↑ Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th–11th Centuries. Leiden: BRILL. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8.

- ↑ , p. 303 https://books.google.com/books?id=DmB_AgAAQBAJ Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, p. 146

- 1 2 Partha Mitter, Indian art, Oxford University Press, 2001 pp.66

- ↑ Agnihotri, V.K. (2010). Indian History. Vol.26. p.B8. "There were many branches of the Pratiharas: Pratiharas of Mandsor, Pratiharas of Nandipuri, Pratiharas of Idar, Pratiharas of Rajor inscription (the nomenclature Gurjara-Pratiharas is based on this inscription only) etc."

- ↑ Goyal, Shankar (1991), "Recent Historiography of the Age of Harṣa", Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 72/73 (1/4): 331–361, JSTOR 41694902 Quote: "From his Harṣacarita we learn that that Prabhäkaravardhana, the father of Harṣa, defeated not only the Hûṇas and Gāndhāras but also the rulers of Sindha, Lāta, Mälava and Gurjara kingdoms."

- ↑ Bakshi, S. R.; Gajrani, S.; Singh, Hari, eds. (2005). Early Aryans to Swaraj. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-7625-537-8."The undated Gwalior (Sagar-Tal) stone inscription of Bhoja I, according to which the ancestor of the family was Samutri or Lakshmana, the younger brother of the epic hero Rama, who was the 'doorkeeper' (Pratihara)"

- ↑ Agnihotri, V.K. (2010). Indian History. Vol.26. p.B8. "Modern historians believed that the name was derived from one of the kings of the line holding the office of Pratihara in the Rashtrakuta court"

- ↑ Shanta Rani Sharma 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Puri 1986.

- 1 2 Sanjay Sharma 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Shanta Rani Sharma 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Tripathi, Ramashankar (1989). History of Kanauj: To the Moslem Conquest. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 221. ISBN 978-81-208-0404-3.

- ↑ Bakshi, S. R.; Gajrani, S.; Singh, Hari, eds. (2005). Early Aryans to Swaraj. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. p. 325. ISBN 81-7625-537-8.

It has been reported that the story of agnikula is mot mentioned at all in the original version of the Raso preserved in the Fort Library at Bikaner.

- ↑ Tripathi, Ramashankar (1999) [1942]. History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 318. ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2.

- ↑ "Journal of Indian History, Volume 41". Journal of Indian history (Dept. of History, University of Kerala) 41: 765. 1963.

Why should not the expression Gurjara Pratihārānvayah, of the Rajor inscription, which was incised more than a hundred years later than Bhoja's Gwalior prasasti, nearly fifty years later than the works of the poet Rajasekhara ...

- ↑ Tripathi, Ramashankar (1989). History of Kanauj: To the Moslem Conquest. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 222. ISBN 978-81-208-0404-3.

- ↑ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 207. ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

- ↑ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (2002) [1976]. Readings in Political History of India, Ancient, Mediaeval, and Modern. Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies. p. 209.

But he (Mr. Sharma) refused to believe that the Imperial Pratiharas of Kanauj were also Gujars in this sense.

- ↑ Puri 1986, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ V. B. Mishra 1954, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ K. M. Munshi, The Glory that was Gurjaradēśa, Vol. III, pp. 5–6, quoted in V. B. Mishra (1954, p. 51)

- ↑ V. B. Mishra 1954, p. 51.

- ↑ Chopra, Pran Nath (2003). A Comprehensive History of Ancient India. Sterling Publishers. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-81-207-2503-4.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004) [1986]. A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- ↑ Sen, S.N., 2013, A Textbook of Medieval Indian History, Delhi: Primus Books, ISBN 9789380607344

- ↑ Kala, Jayantika (1988). Epic scenes in Indian plastic art. Abhinav Publications. p. 5. ISBN 81-7017-228-4, ISBN 978-81-7017-228-4.

- ↑ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 207. ISBN 81-269-0027-X,ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

The king of Gurjars maintain numerous faces and no other Indian prince has so fine a cavalry .He has

- ↑ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 207 to 208. ISBN 81-269-0027-X, ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

- Sources

- Mishra, V. B. (1954). "Who were the Gurjara-Pratīhāras?". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 35 (1/4): 42–53. JSTOR 41784918.

- Puri, Baij Nath (1986). The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Sharma, Sanjay (2006). "Negotiating Identity and Status Legitimation and Patronage under the Gurjara-Pratīhāras of Kanauj". Studies in History 22 (22): 181–220. doi:10.1177/025764300602200202.

- Sharma, Shanta Rani (2012). "Exploding the Myth of the Gūjara Identity of the Imperial Pratihāras". Indian Historical Review 39 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1177/0376983612449525.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||