Günther von Kluge

| Günther "Hans" von Kluge | |

|---|---|

Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge | |

| Nickname(s) | Der kluge Hans |

| Born |

30 October 1882 Posen, Province of Posen, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire now Poznań, Greater Poland, Poland |

| Died |

19 August 1944 (aged 61) Metz, Gau Westmark, Nazi Germany now Metz, Lorraine, France |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1901–44 |

| Rank | Generalfeldmarschall |

| Unit |

Reichswehr 1916–30 Wehrmacht 1930–44 |

| Commands held |

German Fourth Army Army Group Centre |

| Battles/wars | |

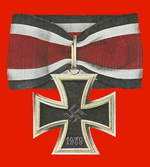

| Awards |

House Order of Hohenzollern Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords |

| Relations |

Wolfgang von Kluge (brother) Karl Ernst Rahtgens (nephew) |

Günther Adolf Ferdinand “Hans” von Kluge (30 October 1882 – 19 August 1944) was a German Field Marshal who served in World War I and World War II. Born into a Prussian military family in Posen (now Poznań, Poland) in 1882, Kluge was a staff officer with the rank of captain by 1916 at the Battle of Verdun. He ultimately rose to the rank of field marshal in the Wehrmacht, which was conveyed at the 1940 Field Marshal Ceremony. The well-known Generalleutnant Wolfgang von Kluge was his younger brother, and another German officer and active resistance fighter against the Nazi régime, Oberstleutnant Karl Ernst Rahtgens, was his nephew.

Kluge commanded on the Eastern and Western Fronts, and was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords (German: Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern).[N 1] Although Kluge was not an active conspirator in the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, his nephew was. But Kluge himself was previously involved with the German military resistance, and had become convinced at the Eastern Front that Hitler was mad. He committed suicide on 19 August 1944, after having been recalled to Berlin for a meeting with Hitler in the aftermath of the failed coup. He was replaced by Field Marshal Walter Model. His suicide opened the eyes of Gestapo and SS to find traitors also among the high-ranked officers at the Western Front, such as Generalleutnant Hans Speidel and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

Early career

During the First World War, Kluge was a staff officer, and in 1916 he was at the Battle of Verdun. Remaining in the Reichswehr after the war, by 1936 he was a lieutenant-general, and in 1937 he took command of the Sixth Army.

Second World War

Invasion of Poland and France

As commander of the Sixth Army Group, which became the German Fourth Army, Kluge led the Sixth into battle in Poland in 1939. He had a central role in the death sentences for twenty-eight Polish prisoners taken in the Defense of the Polish Post Office in Danzig. Though he opposed the initial German plan to attack westwards into France, he led the Fourth Army in its attack through the Ardennes that culminated in the fall of France. Kluge was promoted to field marshal in July 1940.

Soviet Union

Kluge commanded the Fourth Army at the opening of Operation Barbarossa, where he developed a strained relationship with Heinz Guderian over tactical issues in the advance, accusing Guderian of frequent disobedience of his orders. On 29 June Kluge ordered that, ‘Women in uniform are to be shot.’[1]

After Fedor von Bock was relieved of his command of Army Group Center in late 1941, Kluge was promoted and led that army group until he was injured in October 1943. Kluge frequently rode in an airplane to inspect the divisions under his command and sometimes relieved his boredom during the flights by hunting foxes from the air[2]—a decidedly non-traditional method. On 30 October 1942 Kluge was the beneficiary of an enormous bribe from Hitler who mailed a letter of good wishes together with a huge cheque made out to him from the German treasury and a promise that whatever improving his estate might cost could be billed out to the German treasury.[3] Kluge took the money, but after receiving severe criticism from his Chief of Staff, Henning von Tresckow who upbraided him for his corruption, he agreed to meet Carl Friedrich Goerdeler in November 1942.[4] Kluge promised Goerdeler that he would arrest Hitler the next time he came to the Eastern Front, but then receiving another "gift" from Hitler, changed his mind and decided to stay loyal.[5] Hitler, who seems to have heard that Kluge was dissatisfied with his leadership regarded his "gifts" as entitling him to Kluge's total loyalty.[5] On 27 October 1943 Kluge was badly injured when his car overturned on the Minsk–Smolensk road. He was unable to return to duty until July 1944. After his recovery he became commander of the German forces in the West (Oberbefehlshaber West) as Gerd von Rundstedt’s replacement.

France and the Western Front

Between June and July 1944, during the invasion of Normandy by Allied forces, Rommel commanded Army Group B under Field Marshal von Rundstedt. Rommel was charged with planning German counterattacks intended to drive the Allied forces back to the beaches. On 5 July Kluge replaced Rundstedt, because Rundstedt was advocating negotiation with the Allies. Two weeks later, Rommel was wounded and Kluge took over as commander of Army Group B as well, where Kluge's forces around the town of Falaise were encircled by combined U.S., Canadian, British, and Polish armies.

In August, after the failed coup attempt by Stauffenberg, Kluge was recalled to Berlin and replaced by Model.

Opposition to Hitler

A leading figure of the German military resistance, Henning von Tresckow, served as his Chief of Staff of Army Group Centre. Kluge was somewhat involved in the military resistance. He knew about Tresckow’s plan to shoot Hitler during a visit to Army Group Centre, having been informed by his former subordinate, Georg von Boeselager, who was now serving under Tresckow. At the last moment, Kluge aborted Tresckow's plan. Boeselager later speculated that because Heinrich Himmler had decided not to accompany Hitler, Kluge feared that without eliminating Himmler too, it could lead to a civil war between the SS and the Wehrmacht.[6]

When Stauffenberg attempted to assassinate Hitler on 20 July, Kluge was Oberbefehlshaber West ("Supreme Field Commander West") with his headquarters in La Roche-Guyon. The commander of the occupation troops of France, General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel, and his colleague Colonel Cäsar von Hofacker – a cousin of Stauffenberg – came to visit Kluge. Stülpnagel had just ordered the arrest of the SS units in Paris. Kluge had already learned that Hitler had survived the assassination attempt and refused to provide any support. "Ja – wenn das Schwein tot wäre!" ("Yes – if the pig were dead!)" he said.[7] On 17 August he was replaced by Walter Model and recalled to Berlin for a meeting with Hitler after the coup failed; thinking that Hitler would punish him as a conspirator, he committed suicide by taking cyanide near Metz two days later on 19 August. He left Hitler a letter in which he advised him to make peace, and to show "the greatness that will be needed to put an end to a hopeless struggle." Hitler reportedly handed the letter to Alfred Jodl and commented that "There are strong reasons to suspect that had not Kluge committed suicide he would have been arrested anyway."[8] SS officer Jürgen Stroop boasted of his involvement in investigating von Kluge for involvement in the plot. He claimed to have offered the Field Marshal the opportunity to commit suicide, but that Kluge refused. He then claimed to have personally shot him and that Himmler had ordered him to announce that Kluge had committed suicide.[9]

Kluge's nickname among the troops and his fellow officers was der kluge Hans ("Clever Hans"). This nickname was acquired early in his career, partly in admiration of his cleverness and partly as a pun on his name (klug is German for "clever"). The "Hans" component came not from any of his given names but from Clever Hans, a horse which became famous for its apparent ability to do arithmetic.

Dates of rank

- Leutnant – 22 March 1901

- Oberleutnant – 16 June 1910

- Hauptmann – 2 August 1914

- Major – 1 April 1923

- Oberstleutnant – 1 July 1927

- Oberst – 1 February 1930

- Generalmajor – 1 February 1933

- Generalleutnant – 1 April 1934

- General der Artillerie – 1 August 1936

- Generaloberst – 1 October 1939

- Generalfeldmarschall – 19 July 1940

Awards

- Iron Cross (1914) 2nd and 1st class

- House Order of Hohenzollern Knight's Cross with Swords

- Bavarian Military Merit Order, 4th class with Swords

- Mecklenburg-Schwerin Military Merit Cross 2nd class

- Order of the Iron Crown, 3rd class with War Decoration

- Austrian Military Merit Cross, 3rd class with War Decoration

- Oldenburg Medal for rescue from danger

- Wound Badge (1918) in Black

- Honour Cross of the World War 1914/1918

- Anschluss Medal

- Sudetenland Medal

- Clasp to the Iron Cross (1939)

- Eastern Front Medal

- Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords

- Knight's Cross on 30 September 1939 as General der Artillerie and commander-in-chief of the 4. Armee[11][12]

- 181st Oak Leaves on 18 January 1943 as Generalfeldmarschall and commander-in-chief of the Heeresgruppe Mitte[11][13]

- 40th Swords on 29 October 1943 as Generalfeldmarschall and commander-in-chief of the Heeresgruppe Mitte[11][14]

- Mentioned four times in the Wehrmachtbericht (7 August 1941, 18 October 1941, 19 October 1941, 3 September 1943)

Wehrmachtbericht references

| Date | Original German Wehrmachtbericht wording | Direct English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Thursday, 7 August 1941 | Am Verlauf dieser gewaltigen Schlacht waren die Armeen des Generalfeldmarschalls von Kluge und der Generalobersten Strauß und Freiherr von Weichs, die Panzergruppen der Generalobersten Guderian und Hoth sowie die Luftwaffenverbände der Generale der Flieger Loerzer und Freiherr von Richthofen ruhmreich beteiligt.[15] | During the course of this great battle, the armies of Field Marshal von Kluge, Colonel General Strauß, and Freiherr von Weichs, the Armoured groups of Colonel-Generals Guderian and Hoth, and the Air Force detachments of Generals of the Air Loerzer and Baron von Richthofen were involved gloriously. |

| Saturday, 18 October 1941 | (Sondermeldung) An der Durchführung dieser Operationen waren die Armeen des Generalfeldmarschalls von Kluge, der Generalobersten Freiherr von Weichs und Strauß sowie Panzerarmeen der Generalobersten Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner und des Generals der Panzertruppen Reinhardt beteiligt.[16] | (Special Bulletin) In the execution of these operations were involved, the armies of Field Marshal von Kluge, Colonel-Generals Freiherr von Weichs and Strauss as well as tank armies of Colonel-General Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner and General of Armoured Forces Reinhardt. |

| Sunday, 19 October 1941 | An der Durchführung dieser Operationen waren die Armeen des Generalfeldmarschalls von Kluge, der Generalobersten Freiherr von Weichs und Strauß sowie Panzerarmeen der Generalobersten Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner und des Generals der Panzertruppen Reinhardt beteiligt.[17] | In the execution of these operations were involved, the armies of Field Marshal von Kluge, Colonel-Generals Freiherr von Weichs and Strauss as well as tank armies of Colonel-General Guderian, Hoth, Hoeppner and General of Armoured Forces Reinhardt. |

References

- Notes

- ↑ The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross and its higher grade Oak Leaves and Swords was awarded to recognise extreme battlefield bravery or successful military leadership.

- Citations

- ↑ Nor, Johnathan, Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II, http://www.historynet.com/wars_conflicts/world_war_2/3037296.html

- ↑ Hoffmann 1977, p. 276.

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett 1953, p. 529.

- ↑ Wheeler-Bennett 1953, pp. 529–530.

- 1 2 Wheeler-Bennett 1953, p. 530.

- ↑ Knopp 2007, p. 226.

- ↑ Knopp 2007, p. 251.

- ↑ Shirer 1990, pp. 1076–77.

- ↑ Moczarski 1981, p. 226–234.

- 1 2 Thomas 1997, p. 378.

- 1 2 3 Scherzer 2007, p. 451.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 261.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ Fellgiebel 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, p. 639.

- ↑ Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, pp. 701–702.

- ↑ Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, p. 702.

- Bibliography

- Berger, Florian (1999). Mit Eichenlaub und Schwertern. Die höchstdekorierten Soldaten des Zweiten Weltkrieges [With Oak Leaves and Swords. The Highest Decorated Soldiers of the Second World War] (in German). Vienna, Austria: Selbstverlag Florian Berger. ISBN 978-3-9501307-0-6.

- Fellgiebel, Walther-Peer (2000) [1986]. Die Träger des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939–1945 — Die Inhaber der höchsten Auszeichnung des Zweiten Weltkrieges aller Wehrmachtteile [The Bearers of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939–1945 — The Owners of the Highest Award of the Second World War of all Wehrmacht Branches] (in German). Friedberg, Germany: Podzun-Pallas. ISBN 978-3-7909-0284-6.

- Hoffman, Peter, (tr. Richard Barry) (1977). The History of the German Resistance, 1939–1945. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-08088-0.

- Knopp, Guido (2007). Die Wehrmacht: Eine Bilanz. C. Bertelsmann Verlag. München. ISBN 978-3-570-00975-8.

- Moczarski, Kazimierz; Mariana Fitzpatrick; Jürgen Stroop (1981). Conversations With an Executioner. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-171918-1.

- Schaulen, Fritjof (2004). Eichenlaubträger 1940 – 1945 Zeitgeschichte in Farbe II Ihlefeld - Primozic [Oak Leaves Bearers 1940 – 1945 Contemporary History in Color II Ihlefeld - Primozic] (in German). Selent, Germany: Pour le Mérite. ISBN 978-3-932381-21-8.

- Scherzer, Veit (2007). Die Ritterkreuzträger 1939–1945 Die Inhaber des Ritterkreuzes des Eisernen Kreuzes 1939 von Heer, Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm sowie mit Deutschland verbündeter Streitkräfte nach den Unterlagen des Bundesarchives [The Knight's Cross Bearers 1939–1945 The Holders of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross 1939 by Army, Air Force, Navy, Waffen-SS, Volkssturm and Allied Forces with Germany According to the Documents of the Federal Archives] (in German). Jena, Germany: Scherzers Miltaer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-938845-17-2.

- Shirer, William L. (1990). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-72868-7.

- Thomas, Franz (1997). Die Eichenlaubträger 1939–1945 Band 1: A–K [The Oak Leaves Bearers 1939–1945 Volume 1: A–K] (in German). Osnabrück, Germany: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-2299-6.

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John (2005) [1953]. The Nemesis of Power: German Army in Politics, 1918 – 1945. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4039-1812-3.

- Die Wehrmachtberichte 1939–1945 Band 1, 1. September 1939 bis 31. Dezember 1941 [The Wehrmacht Reports 1939–1945 Volume 1, 1 September 1939 to 31 December 1941] (in German). München, Germany: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH & Co. KG. 1985. ISBN 978-3-423-05944-2.

External links

- Günther von Kluge @ Geocities at the Wayback Machine (archived October 29, 2009)

- Hans Günther von Kluge

- Burial of Günther von Kluge in Böhne

- Günther von Kluge – Generalfeldmarschall and Gutsherr von Böhne

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by none |

Commander of 4. Armee 1 December 1938 – 19 December 1941 |

Succeeded by General der Gebirgstruppe Ludwig Kübler |

| Preceded by Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock |

Commander of Heeresgruppe Mitte 19 December 1941 – 12 October 1943 |

Succeeded by Generalfeldmarschall Ernst Busch |

| Preceded by Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt |

Commander of Heeresgruppe D 2 July 1944 – 15 August 1944 |

Succeeded by Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt |

| Preceded by Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt |

Oberbefehlshaber West 2 July 1944 – 16 August 1944 |

Succeeded by Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model |

| Preceded by Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel |

Commander of Heeresgruppe B 19 July 1944 – 17 August 1944 |

Succeeded by Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|