Duchenne de Boulogne

| Duchenne de Boulogne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

September 17, 1806 Boulogne |

| Died |

September 15, 1875 (aged 68) Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | neurology |

| Known for | electrophysiology |

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne (de Boulogne) (September 17, 1806, in Boulogne-sur-Mer – September 15, 1875, in Paris) was a French neurologist who revived Galvani's research and greatly advanced the science of electrophysiology. The era of modern neurology developed from Duchenne's understanding of the conductivity of neural pathways, his revelations of the effect of lesions on these structures and his diagnostic innovations including deep tissue biopsy, nerve conduction tests (NCS), and clinical photography.

Neurology did not exist in France before Duchenne and although many medical historians regard Jean-Martin Charcot as the father of the discipline, Charcot owed much to Duchenne, often acknowledging him as, "mon maître en neurologie" (my teacher in neurology).[1][2][3][4] The American neurologist Dr. Joseph Collins (1866–1950) wrote that Duchenne found neurology, "a sprawling infant of unknown parentage which he succored to a lusty youth."[5] His greatest contributions were made in the myopathies that came to immortalize his name, Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, Duchenne-Aran spinal muscular atrophy, Duchenne-Erb paralysis, Duchenne's disease (Tabes dorsalis), and Duchenne's paralysis (Progressive bulbar palsy). He was the first clinician to practise muscle biopsy, the harvesting of in vivo tissue samples with an invention he called, "l'emporte-pièce" (Duchenne's trocar).[6] In 1855 he formalized the diagnostic principles of electrophysiology and introduced electrotherapy in a textbook titled, De l'electrisation localisée et de son application à la physiologie, à la pathologie et à la thérapeutique.[7] A companion atlas to this work titled, Album de photographies pathologiques, was the first neurology text illustrated by photographs. Duchenne's monograph, Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine – also illustrated prominently by his photographs – was the first study on the physiology of emotion and was seminal to Darwin's later work.[3]

Biography

Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne was the son of a fisherman, descended from a long line of mariners who had settled in the Boulogne-sur-Mer region of France. In opposition to his father's wishes that he become a sailor, and driven by an innate love for science, Duchenne enrolled at the University of Douai where he received his Baccalauréat at the age of 19.[8] He then trained under a number of distinguished Paris physicians including René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laënnec (1781–1826), Baron Guillaume Dupuytren (1777–1835), François Magendie (1783–1855), and Léon-Jean-Baptiste Cruveilhier (1791–1874).[9] He graduated in medicine in Paris in 1831 and presented his Thèse de Médecine, a monograph on burns, before returning to his native Boulogne where he opened a practice. Duchenne married in 1831, but his wife died of puerperal fever during childbirth two years later. Duchenne’s mother in law spread rumours that the death of his wife was caused by the fact that only he was present at the delivery, and after this he was kept separate from his only son by his wife’s family, only to be reunited with him towards the end of his life.

In 1835, Duchenne began experimenting with therapeutic "électropuncture" (a technique recently invented by Magendie and Jean-Baptiste Sarlandière by which electric shock was administered beneath the skin with sharp electrodes to stimulate the muscles). After a brief and unhappy second marriage, Duchenne returned to Paris in 1842 in order to continue his medical research. There, he developed a non-invasive technique of muscle stimulation that used faradic shock on the surface of the skin, which he called "électrisation localisée". He articulated these theories in his work, On Localized Electrization and its Application to Pathology and Therapy, first published in 1855.[7] A pictorial supplement to the second edition, Album of Pathological Photographs (Album de Photographies Pathologiques) was published in 1862. A few months later, the first edition of his now much-discussed work, The Mechanism of Human Physiology,[10] was published. Were it not for this small, but remarkable, work, his next publication, the result of nearly 20 years of study, Duchenne's Physiology of Movements, Demonstrated with the Aid of Electrical Experimentation and Clinical Observation, and Applicable to the Study of Paralyses and Deformations,[11] his most important contribution to medical science, might well have gone unnoticed.

Despite his unorthodox procedures, and his often uncomfortable relations with the senior medical staff with whom he worked, Duchenne's single-mindedness and relentless and exacting research, soon obtained him an international standing as a neurologist at the forefront of his field. Moreover, he is considered as one of the developers of electro-physiology and electro-therapeutics. By electricity he also determined that smiles resulting from true happiness not only utilize the muscles of the mouth but also those of the eyes. Such "genuine" smiles are known as Duchenne smiles in his honor. He is also credited with the discovery of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Duchenne died of haemorrhagic bleeding in 1875, after several years of illness.

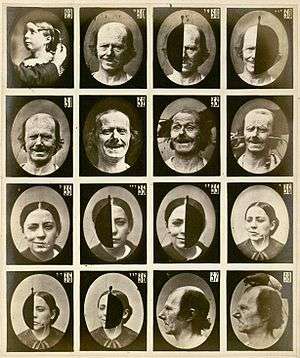

Duchenne effectively used the newly invented medium of photography to capture electrically induced expressions of his subjects, but wasn't able to record the actual movement of the facial muscles, a fact he complained about in his writings.

The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression

.jpg)

Influenced by the fashionable beliefs of physiognomy of the 19th century, Duchenne wanted to determine how the muscles in the human face produce facial expressions which he believed to be directly linked to the soul of man. He is known, in particular, for the way he triggered muscular contractions with electrical probes, recording the resulting distorted and often grotesque expressions with the recently invented camera. He published his findings in 1862, together with extraordinary photographs of the induced expressions, in the book Mecanisme de la physionomie Humaine (The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression, also known as The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy).

Duchenne believed that the human face was a kind of map, the features of which could be codified into universal taxonomies of inner states; he was convinced that the expressions of the human face were a gateway to the soul of man. Unlike Lavater and other physiognomists of the era, Duchenne was skeptical of the face's ability to express moral character; rather he was convinced that it was through a reading of the expressions alone (known as pathognomy) which could reveal an "accurate rendering of the soul's emotions".[12] He believed that he could observe and capture an "idealized naturalism" in a similar (and even improved) way to that observed in Greek art. It is these notions that he sought conclusively and scientifically to chart by his experiments and photography and it led to the publishing of The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy in 1862[13] (also entitled, The Electro-Physiological Analysis of the Expression of the Passions, Applicable to the Practice of the Plastic Arts. in French: Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine, ou Analyse électro-physiologique de l'expression des passions applicable à la pratique des arts plastiques), now generally rendered as The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression. The work compromises a volume of text divided into three parts:

- General Considerations,

- A Scientific Section, and

- An Aesthetic Section.

These sections were accompanied by an atlas of photographic plates. Believing that he was investigating a God-given language of facial signs, Duchenne writes:

In the face our creator was not concerned with mechanical necessity. He was able in his wisdom or – please pardon this manner of speaking – in pursuing a divine fantasy … to put any particular muscles into action, one alone or several muscles together, when He wished the characteristic signs of the emotions, even the most fleeting, to be written briefly on man's face. Once this language of facial expression was created, it sufficed for Him to give all human beings the instinctive faculty of always expressing their sentiments by contracting the same muscles. This rendered the language universal and immutable.[14]

Duchenne defines the fundamental expressive gestures of the human face and associates each with a specific facial muscle or muscle group. He identifies thirteen primary emotions the expression of which is controlled by one or two muscles. He also isolates the precise contractions that result in each expression and separates them into two categories: partial and combined. To stimulate the facial muscles and capture these "idealized" expressions of his patients, Duchenne applied faradic shock through electrified metal probes pressed upon the surface of the various muscles of the face.

Duchenne was convinced that the "truth" of his pathognomic experiments could only be effectively rendered by photography, the subject's expressions being too fleeting to be drawn or painted. "Only photography," he writes, "as truthful as a mirror, could attain such desirable perfection."[15] He worked with a talented, young photographer, Adrian Tournachon, (the brother of Felix Nadar), and also taught himself the art in order to document his experiments.[16] From an art-historical point of view, the Mechanism of Human Physiognomy was the first publication on the expression of human emotions to be illustrated with actual photographs. Photography had only recently been invented, and there was a widespread belief that this was a medium that could capture the "truth" of any situation in a way that other mediums were unable to do.

Duchenne used six living models in the scientific section, all but one of whom were his patients. His primary model, however, was an "old toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality."[17] Through his experiments, Duchenne sought to capture the very "conditions that aesthetically constitute beauty."[18] He reiterated this in the aesthetic section of the book where he spoke of his desire to portray the "conditions of beauty: beauty of form associated with the exactness of the facial expression, pose and gesture."[19] Duchenne referred to these facial expressions as the "gymnastics of the soul". He replied to criticisms of his use of the old man by arguing that "every face could become spiritually beautiful through the accurate rendering of his or her emotions",[19] and furthermore said that because the patient was suffering from an anesthetic condition of the face, he could experiment upon the muscles of his face without causing him pain.

Aesthetics and The Narrative Setting

Whereas the scientific section was intended to exhibit the expressive lines of the face and the "truth of the expression," the aesthetic section was intended also to demonstrate that the "gesture and the pose together contribute to the expression; the trunk and the limbs must be photographed with as much care as the face so as to form an harmonious whole."[20] For these plates Duchenne used a partially blind young woman who he claimed "had become accustomed to the unpleasant sensation of this treatment …".[21] As in many of the plates for the scientific section, this model was also stimulated faradically to provoke a different expression on either side of her face. Duchenne advised that looking at both sides of the face simultaneously would reveal only a "mere grimace" and he urged the reader to examine each side separately and with care.

Duchenne's experiments for the aesthetic section of the Mechanism included the use of performance and narratives which may well have been influenced by gestures and poses found in the pantomime of the period. He believed that only by electroshock and in the setting of elaborately constructed theatre pieces featuring gestures and accessory symbols could he faithfully depict the complex combinatory expressions resulting from conflicting emotions and ambivalent sentiments. These melodramatic tableaux include a nun in "extremely sorrowful prayer" experiencing "saintly transports of virginal purity"; a mother feeling both pain and joy while leaning over a child's crib; a bare-shouldered coquette looking at once offended, haughty and mocking; and three scenes from Lady Macbeth expressing the "aggressive and wicked passions of hatred, of jealousy, of cruel instincts," modulated to varying degrees of contrary feelings of filial piety.[22] This theatre of pathognomic effect dominates the aesthetic section of the Mecanisme.

Beauty and Truth

To help him locate and identify the facial muscles, Duchenne drew heavily upon the work of Charles Bell, although he did not share the Scottish anatomist's interest in the expressions found in insanity. Duchenne may have avoided photographing the "passions" of the insane because of technical problems at the time; however, it is much more likely that he did so for aesthetic reasons – simply, that he did not regard the expressions of the insane as socially acceptable. Interestingly, Charles Bell's writings also showed an instinctive revulsion for the mentally ill.

The exact imitation of nature was for Duchenne the sine qua non of the finest art of whatever age, and although he praised the ancient Greek sculptors for unquestionably attaining an ideal of beauty, he nevertheless criticized them for their anatomical errors and failure to attend to the emotions. Thus at the end of the scientific section, for instance, Duchenne "corrects" the expressions of three widely revered classic Greek or Roman antiquities: In no manner, argues Duchenne, do any of these countenances conform to nature as revealed by his electrophysiological research. He even questions the Greek artist Praxiteles's accuracy in sculpting the Niobe:

Would Niobe have been less beautiful if the dreadful emotion of her spirit had bulged the head of her oblique eyebrow as nature does, and if a few lines of sorrow had furrowed the median section of her forehead? On the contrary, nothing is more moving and appealing than such an expression of pain on a young forehead, which is usually so serene.[23]

Duchenne's influence

Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, written, in part, as a refutation of Sir Charles Bell's theologically doctrinaire physiognomy, was published in 1872. This book elaborated on Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection and concentrated on the genetic aspects of human (and animal) behaviour. Darwin's text carried illustrations drawn from Duchenne's photographs, and Darwin and Duchenne corresponded briefly. It is noteworthy, also, that Darwin lent his copy of Duchenne's book to the British psychiatrist James Crichton-Browne in 1869, that Crichton-Browne seems to have mislaid the book for a year or so (in the West Riding lunatic asylum in Wakefield, Yorkshire - see the Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 7220) and that - in 1872 - Crichton-Browne invited Sir David Ferrier to his asylum laboratory to undertake experiments involving the electrical stimulation of motor centres in the brain.

Duchenne's most famous student was Jean-Martin Charcot, who became director of the insane asylum at Salpêtrière in 1862. He adopted Duchenne's procedure of photographic experiments and also believed that it was possible to attain the "truth" through direct observation. He even named an examination room at the asylum after his teacher. Like Duchenne, Charcot sought to chart the gestures and expressions of his patients, believing them to be subject to absolute, mechanistic laws. However, unlike Duchenne, who restricted his experiments to the realm of the sane, Charcot was interested almost exclusively in photographing the expressions of traumatized patients - the "hysterics". He is also known for enabling the public to bear witness to these emotional displays, establishing his renowned weekly "theatre of the passions" for the high society of the day to witness the expressions of the insane. Sigmund Freud, who attended Charcot's clinical demonstrations, constructed his life's work, psychoanalysis, through a demolition of Charcot's neurological theory of hysteria.

In 1981, a modern audience was exposed to Duchenne's The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy when the book and its photographs were revealed - alongside illustrations of phrenology and evolutionary theory - on screen in the film version of John Fowles's novel, The French Lieutenant's Woman. There, the protagonist, Charles Smithson, a young scientist, who "like most men of his time, was still faintly under the influence of the Lavater's Physiognomy,"[24] is intent on interpreting an alienated woman's true character from her expressions.

Perhaps we can best understand Duchenne's contribution to art and science by Robert Sobieszek's concluding words to his comprehensive chapter on Duchenne, in his book Ghost in the Shell[25] where he writes:

Duchenne's ultimate legacy may be that he set the stage, as it were, for Charcot's visual theater of the passions and defined the essential dramaturgy of all the visual theaters, both scientific and artistic, that have since been conceived in the attempt to picture our psyches. … In the end, Duchenne's Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine and the photographic stills from its experimental theater of electroshock excitations established the modern field on which the struggle to depict and thus discern the ever-elusive meanings of our coded faces continues even now to be waged.[26]

Eponymous Diseases

Duchenne's diagnostic innovations

- acute poliomyelitis

- Functional electrical stimulation as a localization test in Neurological examination.

- identified progressive bulbar paralysis

- studies into lead poisoning

- identified pseudohypertrophic muscle dystrophy

- tabetic locomotor ataxia

Works

- Essai sur la brûlure (1833)

- De l'Électrisation localisée et de son application à la physiologie, à la pathologie et à la thérapeutique (1855)

- Paraplegie hypertrophique de l'enfance de cause cerebrale (1861)

- Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine, ou Analyse électro-physiologique de l'expression des passions applicable à la pratique des arts plastiques (1862)

- Physiologie des mouvements démontrée à l'aide de l'expérimentation électrique et de l'observation clinique, et applicable à l'étude des paralysies et des déformations (1867)

References

- ↑ Garrison, Fielding Hudson (1913). An introduction to the history of medicine. Philadelphia & London: W. B. Saunders. p. 571.

Modem neurology is mainly of French extraction and derives from Duchenne, of Boulogne, through Charcot and his pupils.

- ↑ McHenry, Lawrence C. (1969). Garrison's history of neurology. Springfield IL: Charles C. Thomas. p. 270. ISBN 0-398-01261-X.

In the first part of the century neurological works had been published by Cooke, Bell, Hall and others, but the first real advance in neurology did not come until the clinical experience of Romberg and Duchenne.

- 1 2 Duchenne de Boulogne, G.-B. & Cuthbertson, Andrew R. (1990). The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression. Cambridge UK; New York; etc.: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-521-36392-6.

It must be emphasized that, before Duchenne, French neurology did not exist.

- ↑ McHenry, p. 282: "His interest in neurology, which was slow in evolving, was largely inspired by Duchenne, whom Charcot called his "master in neurology."

- 1 2 Collins, Joseph (1908). "Duchenne of Boulogne. A biography and an appreciation". Medical Record (William Wood) 73: 50–54.

- ↑ This device was described by Gowers as 'Duchenne's histological harpoon,' and by others as a 'miniature harpoon' - metonymy that alluded to his parentage by the sea.

- 1 2 Duchenne, Guillaume-Benjamin & Tibbets, Herbert (1871). A treatise on localized electrization, and its applications to pathology and therapeutics. London: Hardwicke.

- ↑ Lasègue, C. & Straus, J. (1875). "Duchenne de Boulogne; sa vie scientifique et ses oeuvres". Archives générales de médecine. 6th (P. Asselin) 2: 687–715.

- ↑ Garrison, p. 572.

- ↑ Mécanisme de la Physiologie Humaine, Ist Edition 1862-3; 2nd Edition, published Paris, J.B. Baillière, 1876

- ↑ Physiologie des mouvements démontrée à l'aide de l'expérimentation électrique et de l'observation clinique, et applicable à l'étude des paralysies et des déformation, published in 1867

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part 3, 130-1, trans. Sobieszek.

- ↑ Also known as The publication history of Duchenne's Mecanisme is complex and to a degree uncertain. It was published over the course of 1862 and possibly into 1863.

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part I, 31; Cuthbertson trans., 19.

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part I, 65; Cuthbertson trans., 36.

- ↑ Although Tournachon contributed some of the negatives for the scientific section, most of the photographs in this section, and all eleven plates corresponding to the aesthetic section, were made by Duchenne.

- ↑ Duchenne, Mechanism, part 2, 6; Cuthbertson trans., 42

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part 2, 8; Cuthbertson trans., 43.

- 1 2 Duchenne, Mecanisme, part 3, 133; Cuthbertson trans., 102

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part 3, 133-5; Cuthbertson trans., 102-3

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part 3, 141; Cuthbertson trans., 105

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part 3, 169-74; Cuthbertson trans., 120-2

- ↑ Duchenne, Mecanisme, part 2, 125; Cuthbertson trans., 100.

- ↑ Fowles The French Lieutenant's Woman, 119

- ↑ The book Ghost in the Shell: Photography and the Human Soul, 1850–2000, by Robert A. Sobieszek, was published in 1999 and accompanied the exhibition of the same name which took place in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

- ↑ Sobieszek, Ghost in the Shell, 2003, MIT Press, 79

Further reading

- Freitas-Magalhães, A., & Castro, E. (2009). The Neuropsychophysiological Construction of the Human Smile. In A. Freitas-Magalhães (Ed.), Emotional Expression: The Brain and The Face (pp. 1–18). Porto: University Fernando Pessoa Press. ISBN 978-989-643-034-4.

- Sobieszek, Robert A., Ghost in the Shell, 2003, MIT Press

- Delaporte, François. Anatomy of the Passions. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

- Parent, André (August 2005). "Duchenne De Boulogne: a pioneer in neurology and medical photography". The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques 32 (3): 369–77. PMID 16225184.

- Parent, André (November 2005). "Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–1875)". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 11 (7): 411–2. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.04.004. PMID 16345141.

- Siegel, I M (2000). "Charcot and Duchenne: of mentors, pupils, and colleagues". Perspect. Biol. Med. 43 (4): 541–7. doi:10.1353/pbm.2000.0055. PMID 11058990.

- Bach, J R (April 2000). "The Duchenne de Boulogne-Meryon controversy and pseudohypertrophic muscular dystrophy". Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences 55 (2): 158–78. doi:10.1093/jhmas/55.2.158. PMID 10820967.

- Pearce, J M (September 1999). "Some contributions of Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–75)". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 67 (3): 322. doi:10.1136/jnnp.67.3.322. PMC 1736523. PMID 10449553.

- Jay, V (1998). "On a historical note: Duchenne of Boulogne". Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 1 (3): 254–5. doi:10.1007/PL00010897. PMID 10463286.

- George, M S (January 1994). "Reanimating the face: early writings by Duchenne and Darwin on the neurology of facial emotion expression". Journal of the history of the neurosciences 3 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1080/09647049409525585. PMID 11618803.

- Ostini, S (March 1993). "[Faradization according to Duchenne de Boulogne (1855)]". Revue médicale de la Suisse romande 113 (3): 245–6. PMID 8480122.

- Borg, K (April 1992). "The man behind the syndrome: Guillaume Duchenne". Journal of the history of the neurosciences 1 (2): 145–54. doi:10.1080/09647049209525526. PMID 11618423.

- Borg, K (March 1991). "[The man behind the syndrome: Guillaume Duchenne. The frozen out "country bumpkin" who showed the way for research on neuromuscular diseases]". Lakartidningen 88 (12): 1091–3. PMID 2016943.

- Reincke, H; Nelson K R (January 1990). "Duchenne de Boulogne: electrodiagnosis of poliomyelitis". Muscle Nerve 13 (1): 56–62. doi:10.1002/mus.880130111. PMID 2183045.

- Nelson, K R; Genain C (October 1989). "Vignette. Duchenne de Boulogne and the muscle biopsy". J. Child Neurol. 4 (4): 315. doi:10.1177/088307388900400413. PMID 2677116.

- Tayeau, F (December 1985). "[My compatriot: Guillaume Duchenne]". Bull. Acad. Natl. Med. 169 (9): 1401–12. PMID 3915439.

- Cuthbertson, R A (1985). "Duchenne de Boulogne and human facial expression". Clinical and experimental neurology 21: 55–67. PMID 3916360.

- Roth, N (1979). "Duchenne and the accuracy esthetic". Medical instrumentation 13 (5): 308. PMID 388166.

- Hueston, J T; Cuthbertson R A (July 1978). "Duchenne de Boulogne and facial expression". Annals of plastic surgery 1 (4): 411–20. PMID 365063.

- Stillings, D (1975). "Darwin and Duchenne". Medical instrumentation 9 (1): 37. PMID 1092967.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guillaume Duchenne. |

- FILM/TV/Director: Documentary DUCHENNE DE BOULOGNE OU L'ANATOMIE DES PASSIONS by Mark Blezinger 1999, 26min

- Artifacial Expression Contemporary artist working on Electro-Facial Choreography.

- Electro-Physiognomy an 1870 book review of Duchenne's monograph, Mécanisme de la Physionomie Humaine..&c.

|