Guanine nucleotide exchange factor

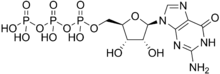

Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) are proteins that activate monomeric GTPases by stimulating the release of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to allow binding of guanosine triphosphate (GTP).[1] A variety of unrelated structural domains have been shown to exhibit guanine nucleotide exchange activity. Some GEFs can activate multiple GTPases while others are specific to a single GTPase.

Function

Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEFs) are proteins involved in the activation of small GTPases. Small GTPases act as molecular switches in intracellular signaling pathways and have many downstream targets. The most well-known GTPases comprise the Ras superfamily and are involved in essential cell processes such as cell differentiation and proliferation, cytoskeletal organization, vesicle trafficking, and nuclear transport.[2] GTPases are active when bound to GTP and inactive when bound to GDP, allowing their activity to be regulated by GEFs and the opposing GTPase activating proteins (GAPs).[3]

GDP dissociates from inactive GTPases very slowly.[3] The binding of GEFs to their GTPase substrates catalyzes the dissociation of GDP, allowing a GTP molecule to bind in its place. GEFs function to promote the dissociation of GDP. After GDP has disassociated from the GTPase, GTP generally binds in its place, as the cytosolic ratio of GTP is much higher than GDP at 10:1.[4] The binding of GTP to the GTPase results in the release of the GEF, which can then activate a new GTPase.[5][6] Thus, GEFs both destabilize the GTPase interaction with GDP and stabilize the nucleotide-free GTPase until a GTP molecule binds to it.[7] GAPs (GTPase-activating protein) act antagonistically to inactivate GTPases by increasing their intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis. GDP remains bound to the inactive GTPase until a GEF binds and stimulates its release.[3]

The localization of GEFs can determine where in the cell a particular GTPase will be active. For example, the Ran GEF, RCC1, is present in the nucleus while the Ran GAP is present in the cytosol, modulating nuclear import and export of proteins.[8] RCC1 converts RanGDP to RanGTP in the nucleus, activating Ran for the export of proteins. When the Ran GAP catalyzes conversion of RanGTP to RanGDP in the cytosol, the protein cargo is released.

Mechanism

The mechanism of GTPase activation varies among different GEFs. However, there are some similarities in how different GEFs alter the conformation of the G protein nucleotide-binding site. GTPases contain two loops called switch 1 and switch 2 that are situated on either side of the bound nucleotide. These regions and the phosphate-binding loop of the GTPase interact with the phosphates of the nucleotide and a coordinating magnesium ion to maintain high affinity binding of the nucleotide. GEF binding induces conformational changes in the P loop and switch regions of the GTPase while the rest of the structure is largely unchanged. The binding of the GEF sterically hinders the magnesium-binding site and interferes with the phosphate-binding region, while the base-binding region remains accessible. When the GEF binds the GTPase, the phosphate groups are released first and the GEF is displaced upon binding of the entering GTP molecule. Though this general scheme is common among GEFs, the specific interactions between the regions of the GTPase and GEF vary among individual proteins.[9]

Structure and Specificity

Some GEFs are specific to a single GTPase while others have multiple GTPase substrates. While different subfamilies of Ras superfamily GTPases have a conserved GTP binding domain, this is not the case for GEFs. Different families of GEFs correspond to different Ras subfamilies. The functional domains of these GEF families are not structurally related and do not share sequence homology. These GEF domains appear to be evolutionarily unrelated despite similar function and substrates.[7]

CDC25 Domain

The CDC25 homology domain, also called the RasGEF domain, is the catalytic domain of many Ras GEFs, which activate Ras GTPases. The CDC25 domain comprises approximately 500 amino acids and was first identified in the CDC25 protein in budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[10]

DH and PH Domains

The Dbl homology and Pleckstrin homology domains are present in all Dbl family members, which act as GEFs for Rho GTPases.[11] The DH domain, also known as the RhoGEF domain, is responsible for GEF catalytic activity. The PH domain is involved in intracellular targeting of the DH domain. The PH domain is generally thought to modulate membrane binding through interactions with phospholipids, but its function has been shown to vary in different proteins.[12][13] This PH domain is also present in other proteins beyond RhoGEFs. Together, these two domains constitute the minimum structural unit necessary for the activity of Dbl family proteins. The PH domain is located immediately adjacent to the C terminus of the DH domain. There are approximately 70 identified Dbl RhoGEFs in humans. Many of the mammalian Dbl family proteins are cell-type specific.[13]

DHR2 Domain

The DHR2 domain is the catalytic domain of the DOCK family of Rho GEFs. The DOCK family is a separate subset of GEFs from the Dbl family and bears no structural or sequence relation to the DH domain. There are 11 identified DOCK family members divided into subfamilies based on their activation of Rac and Cdc42. DOCK family members are involved in cell migration, morphogenesis and phagocytosis. The DHR2 domain is approximately 400 amino acids. These proteins also contain a second conserved domain, DHR1, which is approximately 250 amino acids. The DHR1 domain been shown to be involved in the membrane localization of some GEFs.[14]

Sec7 Domain

The Sec7 domain is responsible for the GEF catalytic activity in ARF GTPases. ARF proteins function in vesicle trafficking. Though ARF GEFs are divergent in their overall sequences, they contain a conserved Sec 7 domain. This 200 amino acid region is homologous to the yeast Sec7p protein.[15]

Regulation

GEFs are often recruited by adaptor proteins in response to upstream signals. GEFs are multi-domain proteins and interact with other proteins inside the cell through these domains.[12] Adaptor proteins can modulate GEF activity by interacting with other domains besides the catalytic domain. For example, SOS1, the Ras GEF in the MAPK/ERK pathway, is recruited by the adaptor protein GRB2 in response to EGF receptor activation. The binding of SOS1 to GBR2 localizes it to the plasma membrane, where it can activate the membrane bound Ras.[16] Other GEFs, such as the Rho GEF Vav1, are activated upon phosphorylation in response to upstream signals.[17] Secondary messengers such as cAMP and calcium can also play a role in GEF activation.[3]

Crosstalk has also been shown between GEFs and multiple GTPase signaling pathways. For example, SOS contains a Dbl homology domain in addition to its CDC25 catalytic domain. SOS can act as a GEF to activate Rac1, a RhoGTPase, in addition to its role as a GEF for Ras. SOS is therefore a link between the Ras-Family and Rho-Family GTPase signaling pathways.[13]

GEFs and Cancer

GEFs are potential target for cancer therapy due to their role in many signaling pathways, particularly cell proliferation. For example, many cancers are caused by mutations in the MAPK/ERK pathway that lead to uncontrolled growth. The GEF SOS1 activates Ras, whose target is the kinase Raf. Raf is a proto-oncogene because mutations in this protein have been found in many cancers.[6][12] The Rho GTPase Vav1, which can be activated by the GEF receptor, has been shown to promote tumor proliferation in pancreatic cancer.[17] GEFs represent possible therapeutic targets as they can potentially play a role in regulating these pathways through their activation of GTPases.

Examples of GEFs

- Son of sevenless (SOS1) is an important GEF in the cell growth-regulatory MAPK/ERK pathway. SOS1 binds GRB2 at the plasma membrane after EGF receptor activation. SOS1 activates the small G protein Ras.[16]

- eIF-2b is a eukaryotic initiation factor necessary to initiate protein translation. eIF-2b regenerates the GTP-bound form of eIF-2 for an additional cycle in protein synthesis initiation, i.e., its binding to the Met-t-RNA.[18]

- G protein-coupled receptors are trans-membrane receptors that act as GEFs for their cognate G proteins upon binding of a ligand. Ligand binding induces a conformational change that allows the GPCR to activate an associated GTPase.[2]

- RCC1 is the guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ran GTPase. It localizes to the nucleus and catalyzes the activation of Ran to allow nuclear export of proteins.[8]

- Ras-GRF1

- Kalirin

See also

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Cherfils, J; Zeghouf, M (Jan 2013). "Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs.". Physiological reviews 93 (1): 269–309. doi:10.1152/physrev.00003.2012. PMID 23303910.

- 1 2 Bruce Alberts; et al. (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science. pp. 877–. ISBN 0815332181. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Bourne, H. R.; Sanders, D. A.; McCormick, F. (1990). "The GTPase superfamily: A conserved switch for diverse cell functions". Nature 348 (6297): 125–132. doi:10.1038/348125a0. PMID 2122258.

- ↑ Bos, J. L.; Rehmann, H.; Wittinghofer, A. (2007). "GEFs and GAPs: Critical Elements in the Control of Small G Proteins". Cell 129 (5): 865–877. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.018. PMID 17540168.

- ↑ Feig, L. A. (1994). "Guanine-nucleotide exchange factors: A family of positive regulators of Ras and related GTPases". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 6 (2): 204–211. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(94)90137-6. PMID 8024811.

- 1 2 Quilliam, L.; Rebhun, J.; Castro, A. (2002). "A growing family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors is responsible for activation of ras-family GTPases". Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology 71: 391–444. doi:10.1016/S0079-6603(02)71047-7.

- 1 2 Cherfils, J.; Chardin, P. (1999). "GEFs: Structural basis for their activation of small GTP-binding proteins". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 24 (8): 306–311. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01429-2. PMID 10431174.

- 1 2 Seki, T.; Hayashi, N.; Nishimoto, T. (1996). "RCC1 in the Ran pathway". Journal of Biochemistry 120 (2): 207–214. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021400. PMID 8889801.

- ↑ Vetter, I. R.; Wittinghofer, A. (2001). "The Guanine Nucleotide-Binding Switch in Three Dimensions". Science 294 (5545): 1299–1304. doi:10.1126/science.1062023. PMID 11701921.

- ↑ Boriack-Sjodin, P. A.; Margarit, S. M.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Kuriyan, J. (1998). "The structural basis of the activation of Ras by Sos". Nature 394 (6691): 337–343. doi:10.1038/28548. PMID 9690470.

- ↑ Zheng, Y. (2001). "Dbl family guanine nucleotide exchange factors". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 26 (12): 724–732. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)01973-9. PMID 11738596.

- 1 2 3 Schmidt, A.; Hall, A. (2002). "Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases: Turning on the switch". Genes & Development 16 (13): 1587–1609. doi:10.1101/gad.1003302.

- 1 2 3 Soisson, S.; Nimnual, A.; Uy, M.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Kuriyan, J. (1998). "Crystal Structure of the Dbl and Pleckstrin Homology Domains from the Human Son of Sevenless Protein". Cell 95 (2): 259–268. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81756-0. PMID 9790532.

- ↑ Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Roe, S. M.; Marshall, C. J.; Barford, D. (2009). "Activation of Rho GTPases by DOCK Exchange Factors is Mediated by a Nucleotide Sensor". Science 325 (5946): 1398–1402. doi:10.1126/science.1174468. PMID 19745154.

- ↑ Jackson, C.; Casanova, J. (2000). "Turning on ARF: The Sec7 family of guanine-nucleotide-exchange factors". Trends in Cell Biology 10 (2): 60–67. doi:10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01699-2. PMID 10652516.

- 1 2 Chardin, P.; Camonis, J.; Gale, N.; Van Aelst, L.; Schlessinger, J.; Wigler, M.; Bar-Sagi, D. (1993). "Human Sos1: A guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras that binds to GRB2". Science 260 (5112): 1338–1343. doi:10.1126/science.8493579. PMID 8493579.

- 1 2 Fernandez-Zapico, M. E.; Gonzalez-Paz, N. C.; Weiss, E.; Savoy, D. N.; Molina, J. R.; Fonseca, R.; Smyrk, T. C.; Chari, S. T.; Urrutia, R.; Billadeau, D. D. (2005). "Ectopic expression of VAV1 reveals an unexpected role in pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis". Cancer Cell 7 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.024. PMID 15652748.

- ↑ Price, N.; Proud, C. (1994). "The guanine nucleotide-exchange factor, eIF-2B". Biochimie 76 (8): 748–760. doi:10.1016/0300-9084(94)90079-5. PMID 7893825.