Degrowth

Degrowth (in French: décroissance,[1] in Spanish: decrecimiento, in Italian: decrescita) is a political, economic, and social movement based on ecological economics, anti-consumerist and anti-capitalist ideas.[2] It is also considered an essential economic strategy responding to the limits-to-growth dilemma (see The Path to Degrowth in Overdeveloped Countries and Post growth). Degrowth thinkers and activists advocate for the downscaling of production and consumption—the contraction of economies—arguing that overconsumption lies at the root of long term environmental issues and social inequalities. Key to the concept of degrowth is that reducing consumption does not require individual martyring or a decrease in well-being.[3] Rather, 'degrowthists' aim to maximize happiness and well-being through non-consumptive means—sharing work, consuming less, while devoting more time to art, music, family, culture and community.

Background

The movement arose from concerns over the perceived consequences of the productivism and consumerism associated with industrial societies (whether capitalist or socialist) including:[4]

- The reduced availability of energy sources (see peak oil)

- The declining quality of the environment (see global warming, pollution, threats to biodiversity)

- The decline in the health of flora and fauna upon which humans depend

- The rise of negative societal side-effects (see unsustainable development, poorer human health, poverty)

- The ever-expanding use of resources by first-world countries to satisfy lifestyles that consume more food and energy, and produce greater waste, at the expense of the third world (see neocolonialism)

Resource depletion

As economies grow, the need for resources grows accordingly. There is a fixed supply of non-renewable resources, such as petroleum (oil), and these resources will inevitably be depleted. Renewable resources can also be depleted if extracted at unsustainable rates over extended periods. For example, this has occurred with 'caviar' production in the Caspian Sea.[5] There is much concern as to how growing demand for these resources will be met as supplies decrease. Many organizations and governments look to energy technologies such as biofuels, solar cells, and wind turbines to meet the demand gap after peak oil. Others have argued that none of the alternatives could effectively replace versatility and portability of oil.[6] Authors of the book Techno-Fix criticize technological optimists for overlooking the limitations of technology in solving agricultural and social challenges arising from growth.[7]

Proponents of degrowth argue that decreasing demand is the only way of permanently closing the demand gap. For renewable resources, demand, and therefore production, must also be brought down to levels that prevent depletion and are environmentally healthy. Moving toward a society that is not dependent on oil is seen as essential to avoiding societal collapse when non-renewable resources are depleted.[8] "But degrowth is not just a quantitative question of doing less of the same, it is also and, more fundamentally, about a paradigmatic re-ordering of values, in particular the (re)affirmation of social and ecological values and a (re)politicisation of the economy".[9]

Ecological footprint

The ecological footprint is a measure of human demand on the Earth's ecosystems. It compares human demand with planet Earth's ecological capacity to regenerate. It represents the amount of biologically productive land and sea area needed to regenerate the resources a human population consumes and to absorb and render harmless the corresponding waste. According to a 2005 Global Footprint Network report,[10] inhabitants of high-income countries live off of 6.4 global hectares (gHa), while those from low-income countries live off of a single gHa. For example, while each inhabitant of Bangladesh lives off of what they produce from 0.56 gHa, a North American requires 12.5 gHa. Each inhabitant of North America uses 22.3 times as much land as a Bangladeshi. According to the same report, the average number of global hectares per person was 2.1, while current consumption levels have reached 2.7 hectares per person. In order for the world's population to attain the living standards typical of European countries, the resources of between three and eight planet Earths would be required. In order for world economic equality to be achieved with the current available resources, rich countries would have to reduce their standard of living through degrowth. The eventual reduction of all available resources would lead to a forced reduction in consumption. Controlled reduction of consumption would reduce the trauma of this change assuming no technological changes increase the planets carrying capacity.

Degrowth and sustainable development

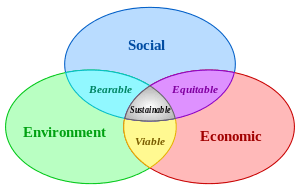

Degrowth thought is in opposition to all forms of productivism (the belief that economic productivity and growth is the purpose of human organization). It is, thus, opposed to the current form of sustainable development.[11] While the concern for sustainability does not contradict degrowth, sustainable development is rooted in mainstream development ideas that aim to increase capitalist growth and consumption. Degrowth therefore sees sustainable development as an oxymoron,[12] as any development based on growth in a finite and environmentally stressed world is seen as inherently unsustainable. Critics of degrowth argue that a slowing of economic growth would result in increased unemployment and increase poverty. Many who understand the devastating environmental consequences of growth still advocate for economic growth in the South, even if not in the North. But, a slowing of economic growth would fail to deliver the benefits of degrowth—self-sufficiency, material responsibility—and would indeed lead to decreased employment. Rather, degrowth proponents advocate for a complete abandonment of the current (growth) economic system, suggesting that relocalizing and abandoning the global economy in the Global South would allow people of the South to become more self-sufficient and would end the overconsumption and exploitation of Southern resources by the North.[12]

"The rebound effect"

Technologies designed to reduce resource use and improve efficiency are often touted as sustainable or green solutions. However, degrowth warns about these technological advances due to the "rebound effect".[13] This concept is based on observations that when a less resource-exhaustive technology is introduced, behaviour surrounding the use of that technology may change, and consumption of that technology could increase or even offset any potential resource savings.[14] In light of the rebound effect, proponents of degrowth hold that the only effective 'sustainable' solutions must involve a complete rejection of the growth paradigm and a move toward a degrowth paradigm.

Origins of the movement

The contemporary degrowth movement can trace its roots back to the anti-industrialist trends of the 19th century, developed in Great Britain by John Ruskin, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement (1819–1900), in the United States by Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), and in Russia by Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910).

The concept of "degrowth" proper appeared during the 1970s, proposed by the Club of Rome think tank and intellectuals such as Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, Jean Baudrillard, André Gorz, Edward Goldsmith and Ivan Illich, whose ideas reflect those of earlier thinkers, such as the economist E. J. Mishan,[15] the industrial historian Tom Rolt,[16] and the radical socialist Tony Turner. The writings of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and J. C. Kumarappa also contain similar philosophies, particularly regarding his support of voluntary simplicity.

More generally, degrowth movements draw on the values of humanism, enlightenment, anthropology and human rights.[17]

The Club of Rome reports

In 1968, the Club of Rome, a think tank headquartered in Winterthur, Switzerland, asked researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for a report on practical solutions to problems of global concern. The report, called The Limits to Growth, published in 1972, became the first important study that indicated the ecological perils of the unprecedented economic growth the world was experiencing at the time.

The reports (also known as the Meadows Reports) are not strictly the founding texts of the movement, as they only advise zero growth, and have also been used to support the sustainable development movement. Still, they are considered the first official studies explicitly presenting economic growth as a key reason for the increase in global environmental problems such as pollution, shortage of raw materials, and the destruction of ecosystems. A second report was published in 1974, and together with the first, drew considerable attention to the topic.

Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen's thesis

The Romanian economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen is considered the creator of degrowth, and its main theoretician.[18] In 1971, he published a book called The Entropy Law and the Economic Process, in which he noted that the neoclassical economic model did not take into account the second law of thermodynamics, by not accounting for the degradation of energy and matter (i.e. increase in entropy). He associated every economic activity with an increase in entropy, whose increase implied the loss of useful resources. When a selection of his articles was translated into French in 1979 under the title Demain la décroissance ("tomorrow, degrowth"), it spurred the creation of the movement in France.

Serge Latouche

Serge Latouche, a professor of economics at the Paris-Sud 11 University, has noted that:

If you try to measure the reduction in the rate of growth by taking into account damages caused to the environment and its consequences on our natural and cultural patrimony, you will generally obtain a result of zero or even negative growth. In 1991, the United States spent 115 billion dollars, or 2.1% of the GDP on the protection of the environment. The Clean Air Act increased this cost by 45 or 55 million dollars per year. [...] The World Resources Institute tried to measure the rate of the growth taking into account the punishment exerted on the natural capital of the world, with an eye towards sustainable development. For Indonesia, it found that the rate of growth between 1971 and 1984 would be reduced from 7.1 to 4% annually, and that was by taking only three variables into consideration: deforestation, the reduction in the reserves of oil and natural gas, and soil erosion.[19][20]

Schumacher and Buddhist economics

E. F. Schumacher's 1973 book Small is Beautiful predates a unified degrowth movement, but nonetheless serves as an important basis for degrowth ideas. In this book he critiques the neo-liberal model of economic development, arguing that an increasing "standard of living", based on consumption, is absurd as a goal of economic activity and development. Instead, under what he refers to as Buddhist economics, we should aim to maximize well-being while minimizing consumption.[21]

Ecological and social issues

In January 1972 Edward Goldsmith and Robert Prescott-Allen—editors of The Ecologist journal—published A Blueprint for Survival, which called for a radical programme of decentralisation and deindustrialisation to prevent what the authors referred to as "the breakdown of society and the irreversible disruption of the life-support systems on this planet".

Degrowth movement

Conferences

The movement has also included international conferences,[22] promoted by the network Research&Degrowth (R&D),[23] in Paris (2008),[24] Barcelona (2010),[25] Montreal[26] Venice (both 2012),[27] Leipzig (2014) and Budapest (2016).[28]

Barcelona Conference (2010)

The First International Conference on Economic Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity of Paris (2008) was a discussion about the financial, social, cultural, demographic, environmental crisis caused by the deficiencies of capitalism and an explanation of the main principles of the degrowth.[29] The Second International Conference of Barcelona on the other hand focused on specific ways to implement a degrowth society.

Concrete proposals have been developed for future political actions, including:

- Promotion of local currencies, elimination of fiat money and reforms of interest

- Transition to non-profit and small scale companies

- Increase of local commons and support of participative approaches in decision-making

- Reducing working hours and facilitation of volunteer work

- Reusing empty housing and co-housing

- Introduction of the basic income guarantee and an income ceiling built on a maximum-minimum ratio

- Limitation of the exploitation of natural resources and preservation of the biodiversity and culture by regulations, taxes and compensations

- Minimize the waste production with education and legal instruments

- Elimination of mega infrastructures, transition from a car-based system to a more local, biking, walking-based one.

- Suppression of advertising from the public space[30]

In spite of the real willingness of reform and the development of numerous solutions, the conference of Barcelona didn’t have a big influence on the world economic and political system. Many critiques have been made concerning the proposals, mostly about the financial aspects, and this has refrained changes to occur.[31]

Criticisms

Liberal critique

Supporters of economic liberalism believe that economic growth brings about the creation of wealth, by increasing employment, improving quality of life, and providing better education and healthcare, in other words, there should be more resources in order to make and improve on more things. From this point of view, degrowth constitutes economic recession and is a destroyer of wealth.

An additional liberal criticism of degrowth is that progress is increasingly linked to knowledge rather than the use of physical resources, and that the progress of technology will solve the world's environmental problems. Free-market environmentalism is a position that argues that most environmental problems are caused by a lack of property rights and the extension of such to include externalities.

Self-regulation of the market

Supporters of the self-regulation of the market believe that if a particular non-renewable resource becomes scarce, the market will limit its extraction via two mechanisms:

- an increase in price (supply and demand)

- an increase in funding for the development of alternatives (i.e., renewable energy, recycling, etc.)

This position argues that allowing market forces to take effect is the most rational way of solving the problem, and consider that these forces are more efficient than centralized decision systems (see economic calculation, dispersed knowledge, tragedy of the commons). Market capitalism can take advantage of the exploitation of energy sources that were not economically viable 10 or 20 years prior, because under new conditions the required economic growth will necessitate their use.

In response to the theories of Georgescu-Roegen, Robert Solow and Joseph Stiglitz noted that capital and labor can substitute for natural resources in production either directly or indirectly, ensuring sustained growth or at least sustainable development.[32]

Creative destruction

The concept of degrowth is founded on the hypothesis that producing more always implies the consumption of more energy and raw materials, while at the same time decreasing the size of the labor force, which is replaced by machines. This analysis is considered misleading from the point of view that technological progress allows us to produce more with less, as well as provide more services. This is what is known as creative destruction, the process by which the "old" companies from a sector (as well as their costly and polluting technologies) disappear from the market as a result of the innovation in that sector that brings down costs while consuming less energy and raw materials in exchange for increased productivity.

At the same time, this reduction in costs and/or increase in profits increases the ability to save, which simultaneously allows for investment in new advances, which will replace the old technologies.

Marxist critique

Marxists distinguish between two types of growth: that which is useful to mankind, and that which simply exists to increase profits for companies. Marxists consider that it is the nature and control of production that is the determinant, and not the quantity. They believe that control and a strategy for growth are the pillars that enable social and economic development. According to Jean Zin, while the justification for degrowth is valid, it is not a solution to the problem.[33] However, other Marxist writers have adopted positions close to the de-growth perspective. For example, John Bellamy Foster[34] and Fred Magdoff,[35] in common with David Harvey, Immanuel Wallerstein, Paul Sweezy and others focus on endless capital accumulation as the basic principle and goal of capitalism. This is the source of economic growth and, in the view of these writers, is unsustainable. Foster and Magdoff develop Marx's own concept of the metabolic rift, something he noted in the exhaustion of soils by capitalist systems of food production.

Third world critique

The concept of degrowth is viewed as contradictory when applied to lesser-developed countries, which require the growth of their economies in order to attain prosperity. In this sense the majority of supporters of degrowth advocate the attainment of a certain, acceptable level of well-being independent of growth. The question of where the balance lies (i.e. how much the developed nations should degrow by, and how much the developing nations should be allowed to grow) remains open.

Systems theoretical critique

In stressing the negative rather than the positive side(s) of growth, the majority of degrowth proponents remains focused on (de-)growth, thus co-performing and further sustaining the actually criticised unsustainable growth obsession. One way out of this paradox might be in changing the reductionist vision of growth as ultimately economic concept, which proponents of both growth and degrowth commonly imply, for a broader concept of growth that allows for the observation of growth in other function systems of society. A corresponding recoding of growth-obsessed or capitalist organisations has recently been proposed.[36]

See also

- A Blueprint for Survival

- Anticapitalism

- Club of Rome

- Development criticism

- Downshifting

- Edward Goldsmith

- Ezra J. Mishan

- François Partant

- Genuine progress indicator

- GROWL

- L-shaped recession

- The Limits to Growth

- Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen

- Political ecology

- Power Down: Options and Actions for a Post-Carbon World

- Serge Latouche

- Simple living

- Paradox of thrift

- Tim Jackson (economist)

- Transition Towns

- Uneconomic growth

- Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt

- The Path to Degrowth in Overdeveloped Countries

Notes

- ↑ Institut d'études économiques et sociales pour la décroissance soutenable.(2003). http://decroissance.org/

- ↑ Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era. Edited by Giacomo D'Alisa, Federico Demaria, Giorgos Kallis. Routledge – 2014 – 248. http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9781138000773/

- ↑ Zehner, Ozzie (2012). Green Illusions. Lincoln & London: U. Nebraska Press. pp. 178–183, 339–342. ISBN 0803237758.

- ↑ Demaria, F., Schneider, F., Sekulova, F., Martinez-Alier, J. (2013). What is degrowth? From an activist slogan to a social movement. Environmental Values 22 (2): 191-215. http://www.degrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/What-is-degrowth.pdf

- ↑ Bardi, U. (2008) 'Peak Caviar'. The Oil Drum: Europe. http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/4367

- ↑ McGreal, R. 2005. 'Bridging the Gap: Alternatives to Petroleum (Peak Oil Part II)'. Raising the Hammer. http://www.raisethehammer.org/index.asp?id=119

- ↑ Huesemann, Michael H., and Joyce A. Huesemann (2011). Technofix: Why Technology Won’t Save Us or the Environment, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada, ISBN 0865717044, 464 pp.

- ↑ Resilience.org. (October 20, 2009). Peak Oil Reports. http://www.resilience.org/stories/2009-10-20/peak-oil-repo rts-oct-20

- ↑ Fournier, V. (2008). Escaping from the economy: politics of degrowth. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. Vol. 28:11/12, pp 528-545.

- ↑ "Data Sources". footprintnetwork.org.

- ↑ "Strong sustainable consumption governance - precondition for a degrowth path?" (PDF).

- 1 2 Latouche, S. (2004).>Degrowth Economics: Why less should be so much more. Le Monde Diplomatique.

- ↑ Zehner, Ozzie (2012). Green Illusions. Lincoln: U. Neb. Pr. pp. 172–73, 333–34.

- ↑ Binswanger, M. (2001), "Technological progress and sustainable development: what about the rebound effect?", Ecological Economics, Vol. 36 pp.119-32.

- ↑ Mishan, Ezra J., The Costs of Economic Growth, Staples Press, 1967

- ↑ Rolt, L. T. C. (1947). High Horse Riderless. George Allen & Unwin. p. 171.

- ↑ D’Alisa, G., Demaria, F., Cattaneo, C. (2013). Civil and Uncivil Actors for a Degrowth Society. Journal of Civil Society 9 (2): 212-224. Special Issue ‘Citizens vs. Markets: How Civil Society is Rethinking the Economy in a Time of Crises. http://www.degrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Dalisa-Demaria-Cattaneo_Civil-and-uncivil-actors-for-a-Degrowth-society_20131.pdf

- ↑ Martin Parker, Valérie Fournier, Patrick Reedy, The Dictionary of Alternatives: Utopianism and Organization, Zed Books, 2007, p. 69.

- ↑ Hervé Kempf, L'économie à l'épreuve de l'écologie Hatier

- ↑ Latouche, Serge (2003) Decrecimiento y post-desarrollo El viejo topo, p.62

- ↑ Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. New York: Perennial Library.

- ↑ (French) « La genèse du Réseau Objection de Croissance en Suisse », Julien Cart, in Moins!, journal romand d'écologie politique, n°12, juillet-août 2014.

- ↑ "Research & Degrowth". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ↑ "Décroissance économique pour la soutenabilité écologique et l'équité sociale". Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ↑ "Degrowth Conference Barcelona 2010". Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ↑ "International Conference on Degrowth in the Americas".

- ↑ "International Degrowth Conference Venezia 2012". Retrieved 5 Dec 2012.

- ↑ http://www.degrowth.org/5-international-degrowth-conference-budapest-2016. Retrieved 14 Apr 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Declaration of the Paris 2008 Conference. Retrieved from: http://degrowth.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Declaration-Degrowth-Paris-2008.pdf

- ↑ 2nd Conference on Economic Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Ethic. 2010. Degrowth Declaration Barcelona 2010 and Working Groups Results. Retrieved from: http://barcelona.degrowth.org/

- ↑ Responsabilité, Innovation & Management. 2011. Décroissance économique pour l’écologie, l’équité et le bien-vivre par François SCHNEIDER. Retrieved from http://www.openrim.org/Decroissance-economique-pour-l.html

- ↑ William D. Sunderlin, Ideology, Social Theory, and the Environment, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002, p. 154-155.

- ↑ L'écologie politique à l'ère de l'information, Ere, 2006, p. 68-69

- ↑ http://monthlyreview.org/press/books/pb2181/, Monthly Review Press.

- ↑ "Harmony and Ecological Civilization: Beyond the Capitalist Alienation of Nature". Monthly Review.

External links

- First International De-growth Conference in Paris 18-19 April 2008

- 2nd Conference on Economic Degrowth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity. Barcelona 26-29 March 2010

- International Conference on Degrowth in the Americas, Montreal, 13-19 May 2012

- 3rd International Conference on degrowth for ecological sustainability and social equity (Venice, 19-23 September 2012)

- Peter Ainsworth on degrowth and sustainable development Published on La Clé des langues

- Club for Degrowth

- CBC Ideas podcast "The Degrowth Paradigm"; 54 minutes (Toronto 10 December 2013)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||