Grothendieck group

In mathematics, the Grothendieck group construction in abstract algebra constructs an abelian group from a commutative monoid in the most universal way. It takes its name from the more general construction in category theory, introduced by Alexander Grothendieck in his fundamental work of the mid-1950s that resulted in the development of K-theory, which led to his proof of the Grothendieck-Riemann-Roch theorem. This article treats both constructions.

Grothendieck group of a commutative monoid

Motivation

Given a commutative monoid M, we want to construct "the most general" abelian group K that arises from M by introducing additive inverses. Such an abelian group K always exists; it is called the Grothendieck group of M. It is characterized by a certain universal property and can also be concretely constructed from M.

Universal property

Let M be a commutative monoid. Its Grothendieck group K is an abelian group with the following universal property: There exists a monoid homomorphism

such that for any monoid homomorphism

from the commutative monoid M to an abelian group A, there is a unique group homomorphism

such that

This expresses the fact that any abelian group A that contains a homomorphic image of M will also contain a homomorphic image of K, K being the "most general" abelian group containing a homomorphic image of M.

Explicit constructions

To construct the Grothendieck group of a commutative monoid M, one forms the Cartesian product

- M×M.

(The two coordinates are meant to represent a positive part and a negative part: (m1, m2) is meant to correspond to the element m1 − m2 in K.)

Addition on MxM is defined coordinate-wise:

- (m1, m2) + (n1, n2) = (m1 + n1, m2 + n2).

Next we define an equivalence relation on M×M. We say that (m1, m2) is equivalent to (n1, n2) if, for some element k of M, m1 + n2 + k = m2 + n1 + k (the element k is necessary because the cancellation law does not hold in all monoids). The equivalence class of the element (m1, m2) is denoted by [(m1, m2)]. We define K to be the set of equivalence classes. Since the addition operation on M×M is compatible with our equivalence relation, we obtain an addition on K, and K becomes an abelian group. The identity element of K is [(0, 0)], and the inverse of [(m1, m2)] is [(m2, m1)]. The homomorphism i : M→K sends the element m to [(m, 0)].

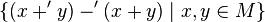

Alternatively, the Grothendieck group K of M can also be constructed using generators and relations: denoting by (Z(M),+') the free abelian group generated by the set M, the Grothendieck group K is the quotient of Z(M) by the subgroup generated by  . (Here +' and -' denote the addition and subtraction in the free abelian group Z(M) while + denotes the addition in the monoid M.) This construction has the advantage that it can be performed for any semigroup M and yields a group which satisfies the corresponding universal properties for semigroups, i.e. the "most general and smallest group containing a homomorphic image of M". This is known as the "group completion of a semigroup" or "group of fractions of a semigroup".

. (Here +' and -' denote the addition and subtraction in the free abelian group Z(M) while + denotes the addition in the monoid M.) This construction has the advantage that it can be performed for any semigroup M and yields a group which satisfies the corresponding universal properties for semigroups, i.e. the "most general and smallest group containing a homomorphic image of M". This is known as the "group completion of a semigroup" or "group of fractions of a semigroup".

Properties

In the language of category theory, any universal construction gives rise to a functor; we thus obtain a functor from the category of commutative monoids to the category of abelian groups which sends the commutative monoid M to its Grothendieck group K. This functor is left adjoint to the forgetful functor from the category of abelian groups to the category of commutative monoids.

For a commutative monoid M, the map i : M→K is injective if and only if M has the cancellation property, and it is bijective if and only if M is already a group.

Examples: the integers, the Grothendieck group of a manifold and of a ring

The easiest example of a Grothendieck group is the construction of the integers Z from the natural numbers N. First one observes that the natural numbers (including 0) together with the usual addition indeed form a commutative monoid (N,+). Now when we use the Grothendieck group construction we obtain the formal differences between natural numbers as elements n - m and we have the equivalence relation

.

.

Now define

![n := [n - 0]](../I/m/61fc0b3bd3eacc6268799170d3fc6e47.png) ,

,![-n := [0 - n]](../I/m/ff0749826d4d09cf221cc27f58daac05.png)

for all n ∈ N. This defines the integers Z. Indeed this is the usual construction to obtain the integers from the natural numbers. See "Construction" under Integers for a more detailed explanation.

The Grothendieck group is the fundamental construction of K-theory. The group K0(M) of a compact manifold M is defined to be the Grothendieck group of the commutative monoid of all isomorphism classes of vector bundles of finite rank on M with the monoid operation given by direct sum. This gives a contravariant functor from manifolds to abelian groups. This functor is studied and extended in topological K-theory.

The zeroth algebraic K group K0(R) of a (not necessarily commutative) ring R is the Grothendieck group of the monoid consisting of isomorphism classes of finitely generated projective modules over R, with the monoid operation given by the direct sum. Then K0 is a covariant functor from rings to abelian groups.

The two previous examples are related: consider the case where R is the ring  of (say complex-valued) smooth functions on a compact manifold M. In this case the projective R-modules are dual to vector bundles over M (by the Serre-Swan theorem). Thus K0(R) and K0(M) are the same group.

of (say complex-valued) smooth functions on a compact manifold M. In this case the projective R-modules are dual to vector bundles over M (by the Serre-Swan theorem). Thus K0(R) and K0(M) are the same group.

Grothendieck group and extensions

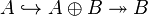

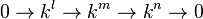

Another construction that carries the name Grothendieck group is the following: Let R be a finite-dimensional algebra over some field k or more generally an artinian ring. Then define the Grothendieck group G0(R) as the abelian group generated by the set ![\{[X] | X \in R\mathrm{-Mod}\}](../I/m/03bd99578e28637826124ce2b54f228a.png) of isomorphism classes of finitely generated R-modules and the following relations: For every short exact sequence

of isomorphism classes of finitely generated R-modules and the following relations: For every short exact sequence

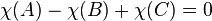

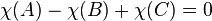

of R-modules add the relation

The abelian group defined by these generators and these relations is the Grothendieck group G0(R).

This group satisfies a universal property. We make a preliminary definition: A function χ from the set of isomorphism classes to an abelian group A is called additive if, for each exact sequence 0 → A → B → C → 0, we have  . Then, for any additive function χ: R-mod → X, there is a unique group homomorphism f: G0(R) → X such that χ factors through f and the map that takes each object of

. Then, for any additive function χ: R-mod → X, there is a unique group homomorphism f: G0(R) → X such that χ factors through f and the map that takes each object of  to the element representing its isomorphism class in G0(R). Concretely this means that f satisfies the equation f([V]) = χ(V) for every finitely generated R-module V and f is the only group homomorphism that does that.

to the element representing its isomorphism class in G0(R). Concretely this means that f satisfies the equation f([V]) = χ(V) for every finitely generated R-module V and f is the only group homomorphism that does that.

Examples of additive functions are the character function from representation theory: If R is a finite-dimensional k-algebra, then we can associate the character χV: R → k to every finite-dimensional R-module V: χV(x) is defined to be the trace of the k-linear map that is given by multiplication with the element x ∈ R on V.

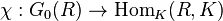

By choosing a suitable basis and writing the corresponding matrices in block triangular form one easily sees that character functions are additive in the above sense. By the universal property this gives us a "universal character"  such that χ([V]) = χV.

such that χ([V]) = χV.

If k = C and R is the group ring C[G] of a finite group G then this character map even gives a natural isomorphism of G0(C[G]) and the character ring Ch(G). In the modular representation theory of finite groups k can be a field  , the algebraic closure of the finite field with p elements. In this case the analogously defined map that associates to each k[G]-module its Brauer character is also a natural isomorphism

, the algebraic closure of the finite field with p elements. In this case the analogously defined map that associates to each k[G]-module its Brauer character is also a natural isomorphism ![G_0(\overline{\mathbf{F}}_p[G])\to \mathrm{BCh}(G)](../I/m/043a57c4341c91c97559d61c96f35f3e.png) onto the ring of Brauer characters. In this way Grothendieck groups show up in representation theory.

onto the ring of Brauer characters. In this way Grothendieck groups show up in representation theory.

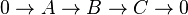

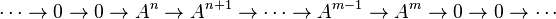

This universal property also makes G0(R) the 'universal receiver' of generalized Euler characteristics. In particular, for every bounded complex of objects in R-mod

we have a canonical element

In fact the Grothendieck group was originally introduced for the study of Euler characteristics.

Grothendieck groups of exact categories

A common generalization of these two concepts is given by the Grothendieck group of an exact category  . Simplified an exact category is an additive category together with a class of distinguished short sequences A → B → C. The distinguished sequences are called "exact sequences", hence the name. The precise axioms for this distinguished class do not matter for the construction of the Grothendieck group.

. Simplified an exact category is an additive category together with a class of distinguished short sequences A → B → C. The distinguished sequences are called "exact sequences", hence the name. The precise axioms for this distinguished class do not matter for the construction of the Grothendieck group.

The Grothendieck group is defined in the same way as before as the abelian group with one generator [M] for each (isomorphism class of) object(s) of the category  and one relation

and one relation

for each exact sequence

.

.

Alternatively one can define the Grothendieck group using a similar universal property: An abelian group G together with a mapping  is called the Grothendieck group of

is called the Grothendieck group of  iff every "additive" map

iff every "additive" map  from

from  into an abelian group X ("additive" in the above sense, i.e. for every exact sequence

into an abelian group X ("additive" in the above sense, i.e. for every exact sequence  we have

we have  ) factors uniquely through φ.

) factors uniquely through φ.

Every abelian category is an exact category if we just use the standard interpretation of "exact". This gives the notion of a Grothendieck group in the previous section if we choose  -mod the category of finitely generated R-modules as

-mod the category of finitely generated R-modules as  . This is really abelian because R was assumed to be artinian and (hence noetherian) in the previous section.

. This is really abelian because R was assumed to be artinian and (hence noetherian) in the previous section.

On the other hand every additive category is also exact if we declare those and only those sequences to be exact that have the form  with the canonical inclusion and projection morphisms. This procedure produces the Grothendieck group of the commutative monoid

with the canonical inclusion and projection morphisms. This procedure produces the Grothendieck group of the commutative monoid  in the first sense (here

in the first sense (here  means the "set" [ignoring all foundational issues] of isomorphism classes in

means the "set" [ignoring all foundational issues] of isomorphism classes in  .)

.)

Grothendieck groups of triangulated categories

Generalizing even further it is also possible to define the Grothendieck group for triangulated categories. The construction is essentially similar but uses the relations [X] - [Y] + [Z] = 0 whenever there is a distinguished triangle X → Y → Z → X[1].

Further examples

- In the abelian category of finite-dimensional vector spaces over a field k, two vector spaces are isomorphic if and only if they have the same dimension. Thus, for a vector space V the class

![[V] = [k^{\mbox{dim}(V)}]](../I/m/d401f9f16d624de47b22b56c47dc51a3.png) in

in  . Moreover for an exact sequence

. Moreover for an exact sequence

- m = l + n, so

- Thus

![[V] = \operatorname{dim}(V)[k]](../I/m/1d5b789b47bf6410522c145a35bc8d17.png) , the Grothendieck group

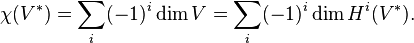

, the Grothendieck group  is isomorphic to Z and is generated by [k]. Finally for a bounded complex of finite-dimensional vector spaces V*,

is isomorphic to Z and is generated by [k]. Finally for a bounded complex of finite-dimensional vector spaces V*,

- where

is the standard Euler characteristic defined by

is the standard Euler characteristic defined by

- For a ringed space

, one can consider the category

, one can consider the category  of all locally free sheaves over X. K0(X) is then defined as the Grothendieck group of this exact category and again this gives a functor.

of all locally free sheaves over X. K0(X) is then defined as the Grothendieck group of this exact category and again this gives a functor.

- For a ringed space

, one can also define the category

, one can also define the category  to be the category of all coherent sheaves on X. This includes the special case (if the ringed space is an affine scheme) of

to be the category of all coherent sheaves on X. This includes the special case (if the ringed space is an affine scheme) of  being the category of finitely generated modules over a noetherian ring R. In both cases

being the category of finitely generated modules over a noetherian ring R. In both cases  is an abelian category and a fortiori an exact category so the construction above applies.

is an abelian category and a fortiori an exact category so the construction above applies.

- In the case where R is a finite-dimensional algebra over some field, the Grothendieck groups G0(R) (defined via short exact sequences of finitely generated modules) and K0(R) (defined via direct sum of finitely generated projective modules) coincide. In fact, both groups are isomorphic to the free abelian group generated by the isomorphism classes of simple R-modules.

- There is another Grothendieck group G0 of a ring or a ringed space which is sometimes useful. The category in the case is chosen to be the category of all quasi-coherent sheaves on the ringed space which reduces to the category of all modules over some ring R in case of affine schemes. G0 is not a functor, but nevertheless it carries important information.

- Since the (bounded) derived category is triangulated, there is a Grothendieck group for derived categories too. This has applications in representation theory for example. For the unbounded category the Grothendieck group however vanishes. For a derived category of some complex finite-dimensional positively graded algebra there is a subcategory in the unbounded derived category containing the abelian category A of finite-dimensional graded modules whose Grothendieck group is the q-adic completion of the Grothendieck group of A.

References

- Michael F. Atiyah, K-Theory, (Notes taken by D.W.Anderson, Fall 1964), published in 1967, W.A. Benjamin Inc., New York.

- Pramod Achar, Catharina Stroppel, Completions of Grothendieck groups, Bulletin of the LMS, 2012.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Grothendieck group", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Grothendieck group at PlanetMath.org.

![[A] - [B] + [C] = 0](../I/m/194ecb7bfdd3b19f439f747b56df5e4b.png)

![[A^\ast] = \sum_i (-1)^i [A^i] = \sum_i (-1)^i [H^i (A^\ast)] \in G_0(R).](../I/m/93e83168f34d199ef2105a2d5ef987ce.png)

![[k^{l+n}] = [k^l] + [k^n] = (l+n)[k].](../I/m/ea4435ac27cef8ad21c56f0952d90855.png)

![[V^*] = \chi(V^*)[k]](../I/m/1a67cb88da9db4a7e2a280f62a296f03.png)