Grothendieck universe

In mathematics, a Grothendieck universe is a set U with the following properties:

- If x is an element of U and if y is an element of x, then y is also an element of U. (U is a transitive set.)

- If x and y are both elements of U, then {x,y} is an element of U.

- If x is an element of U, then P(x), the power set of x, is also an element of U.

- If

is a family of elements of U, and if I is an element of U, then the union

is a family of elements of U, and if I is an element of U, then the union  is an element of U.

is an element of U.

A Grothendieck universe is meant to provide a set in which all of mathematics can be performed. (In fact, uncountable Grothendieck universes provide models of set theory with the natural ∈-relation, natural powerset operation etc.) Elements of a Grothendieck universe are sometimes called small sets. The idea of universes is due to Alexander Grothendieck, who used them as a way of avoiding proper classes in algebraic geometry.

The existence of a nontrivial Grothendieck universe goes beyond the usual axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory; in particular it would imply the existence of strongly inaccessible cardinals. Tarski–Grothendieck set theory is an axiomatic treatment of set theory, used in some automatic proof systems, in which every set belongs to a Grothendieck universe. The concept of a Grothendieck universe can also be defined in a topos. [1]

Properties

As an example, we will prove an easy proposition.

- Proposition. If

and

and  , then

, then  .

. - Proof.

because

because  .

.  because

because  , so

, so  .

.

It is similarly easy to prove that any Grothendieck universe U contains:

- All singletons of each of its elements,

- All products of all families of elements of U indexed by an element of U,

- All disjoint unions of all families of elements of U indexed by an element of U,

- All intersections of all families of elements of U indexed by an element of U,

- All functions between any two elements of U, and

- All subsets of U whose cardinal is an element of U.

In particular, it follows from the last axiom that if U is non-empty, it must contain all of its finite subsets and a subset of each finite cardinality. One can also prove immediately from the definitions that the intersection of any class of universes is a universe.

Grothendieck universes and inaccessible cardinals

There are two simple examples of Grothendieck universes:

- The empty set, and

- The set of all hereditarily finite sets

.

.

Other examples are more difficult to construct. Loosely speaking, this is because Grothendieck universes are equivalent to strongly inaccessible cardinals. More formally, the following two axioms are equivalent:

- (U) For each set x, there exists a Grothendieck universe U such that x ∈ U.

- (C) For each cardinal κ, there is a strongly inaccessible cardinal λ that is strictly larger than κ.

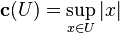

To prove this fact, we introduce the function c(U). Define:

where by |x| we mean the cardinality of x. Then for any universe U, c(U) is either zero or strongly inaccessible. Assuming it is non-zero, it is a strong limit cardinal because the power set of any element of U is an element of U and every element of U is a subset of U. To see that it is regular, suppose that cλ is a collection of cardinals indexed by I, where the cardinality of I and of each cλ is less than c(U). Then, by the definition of c(U), I and each cλ can be replaced by an element of U. The union of elements of U indexed by an element of U is an element of U, so the sum of the cλ has the cardinality of an element of U, hence is less than c(U). By invoking the axiom of foundation, that no set is contained in itself, it can be shown that c(U) equals |U|; when the axiom of foundation is not assumed, there are counterexamples (we may take for example U to be the set of all finite sets of finite sets etc. of the sets xα where the index α is any real number, and xα = {xα} for each α. Then U has the cardinality of the continuum, but all of its members have finite cardinality and so  ; see Bourbaki's article for more details).

; see Bourbaki's article for more details).

Let κ be a strongly inaccessible cardinal. Say that a set S is strictly of type κ if for any sequence sn ∈ ... ∈ s0 ∈ S, |sn| < κ. (S itself corresponds to the empty sequence.) Then the set u(κ) of all sets strictly of type κ is a Grothendieck universe of cardinality κ. The proof of this fact is long, so for details, we again refer to Bourbaki's article, listed in the references.

To show that the large cardinal axiom (C) implies the universe axiom (U), choose a set x. Let x0 = x, and for each n, let xn+1 =  xn be the union of the elements of xn. Let y =

xn be the union of the elements of xn. Let y =  xn. By (C), there is a strongly inaccessible cardinal κ such that |y| < κ. Let u(κ) be the universe of the previous paragraph. x is strictly of type κ, so x ∈ u(κ). To show that the universe axiom (U) implies the large cardinal axiom (C), choose a cardinal κ. κ is a set, so it is an element of a Grothendieck universe U. The cardinality of U is strongly inaccessible and strictly larger than that of κ.

xn. By (C), there is a strongly inaccessible cardinal κ such that |y| < κ. Let u(κ) be the universe of the previous paragraph. x is strictly of type κ, so x ∈ u(κ). To show that the universe axiom (U) implies the large cardinal axiom (C), choose a cardinal κ. κ is a set, so it is an element of a Grothendieck universe U. The cardinality of U is strongly inaccessible and strictly larger than that of κ.

In fact, any Grothendieck universe is of the form u(κ) for some κ. This gives another form of the equivalence between Grothendieck universes and strongly inaccessible cardinals:

- For any Grothendieck universe U, |U| is either zero,

, or a strongly inaccessible cardinal. And if κ is zero,

, or a strongly inaccessible cardinal. And if κ is zero,  , or a strongly inaccessible cardinal, then there is a Grothendieck universe u(κ). Furthermore, u(|U|) = U, and |u(κ)| = κ.

, or a strongly inaccessible cardinal, then there is a Grothendieck universe u(κ). Furthermore, u(|U|) = U, and |u(κ)| = κ.

Since the existence of strongly inaccessible cardinals cannot be proved from the axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory (ZFC), the existence of universes other than the empty set and  cannot be proved from ZFC either. However, strongly inaccessible cardinals are on the lower end of the list of large cardinals; thus, most set theories that use large cardinals (such as "ZFC plus there is a measurable cardinal", "ZFC plus there are infinitely many Woodin cardinals") will prove that Grothendieck universes exist.

cannot be proved from ZFC either. However, strongly inaccessible cardinals are on the lower end of the list of large cardinals; thus, most set theories that use large cardinals (such as "ZFC plus there is a measurable cardinal", "ZFC plus there are infinitely many Woodin cardinals") will prove that Grothendieck universes exist.

See also

References

- ↑ Streicher, Thomas (2006). "Universes in Toposes" (PDF). From Sets and Types to Topology and Analysis: Towards Practicable Foundations for Constructive Mathematics. Clarendon Press. pp. 78–90. ISBN 9780198566519.

Bourbaki, Nicolas (1972). "Univers". In Michael Artin, Alexandre Grothendieck, Jean-Louis Verdier, eds. Séminaire de Géométrie Algébrique du Bois Marie – 1963–64 – Théorie des topos et cohomologie étale des schémas – (SGA 4) – vol. 1 (Lecture notes in mathematics 269) (in French). Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 185–217.