Gröbner basis

In mathematics, and more specifically in computer algebra, computational algebraic geometry, and computational commutative algebra, a Gröbner basis is a particular kind of generating set of an ideal in a polynomial ring over a field K[x1, ..,xn]. A Gröbner basis allows many important properties of the ideal and the associated algebraic variety to be deduced easily, such as the dimension and the number of zeros when it is finite. Gröbner basis computation is one of the main practical tools for solving systems of polynomial equations and computing the images of algebraic varieties under projections or rational maps.

Gröbner basis computation can be seen as a multivariate, non-linear generalization of both Euclid's algorithm for computing polynomial greatest common divisors, and Gaussian elimination for linear systems.[1]

Gröbner bases were introduced in 1965, together with an algorithm to compute them (Buchberger's algorithm), by Bruno Buchberger in his Ph.D. thesis. He named them after his advisor Wolfgang Gröbner. In 2007, Buchberger received the Association for Computing Machinery's Paris Kanellakis Theory and Practice Award for this work. However, the Russian mathematician N. M. Gjunter had introduced a similar notion in 1913, published in various Russian mathematical journals. These papers were largely ignored by the mathematical community until their rediscovery in 1987 by Bodo Renschuch et al.[2] An analogous concept for local rings was developed independently by Heisuke Hironaka in 1964, who named them standard bases.

The theory of Gröbner bases has been extended by many authors in various directions. It has been generalized to other structures such as polynomials over principal ideal rings or polynomial rings, and also some classes of non-commutative rings and algebras, like Ore algebras.

Background

Polynomial ring

Gröbner bases are primarily defined for ideals in a polynomial ring ![R=K[x_1,\ldots,x_n]](../I/m/20d4dd0d2676907a41aea9daff9a7048.png) over a field K. Although the theory works for any field, most Gröbner basis computations are done either when K is the field of rationals or the integers modulo a prime number.

over a field K. Although the theory works for any field, most Gröbner basis computations are done either when K is the field of rationals or the integers modulo a prime number.

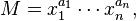

A polynomial is a sum  where the

where the  are nonzero elements of K and the

are nonzero elements of K and the  are monomials or "power products" of the variables. This means that a monomial M is a product

are monomials or "power products" of the variables. This means that a monomial M is a product  where the

where the  are nonnegative integers. The vector

are nonnegative integers. The vector ![A=[a_1, \ldots ,a_n]](../I/m/54c678e74874cbfcf9946ea453742474.png) is called the exponent vector of M. The notation is often abbreviated as

is called the exponent vector of M. The notation is often abbreviated as  . Monomials are uniquely defined by their exponent vectors so computers can represent monomials efficiently as exponent vectors, and polynomials as lists of exponent vectors and their coefficients.

. Monomials are uniquely defined by their exponent vectors so computers can represent monomials efficiently as exponent vectors, and polynomials as lists of exponent vectors and their coefficients.

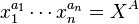

If  is a finite set of polynomials in a polynomial ring R, the ideal generated by F is the set of linear combinations of elements from F with coefficients in all of R:

is a finite set of polynomials in a polynomial ring R, the ideal generated by F is the set of linear combinations of elements from F with coefficients in all of R:

Monomial ordering

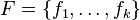

All operations related to Gröbner bases require the choice of a total order on the monomials, with the following properties of compatibility with multiplication. For all monomials M, N, P,

-

-

.

.

A total order satisfying these condition is sometimes called an admissible ordering.

These conditions imply Noetherianity, which means that every strictly decreasing sequence of monomials is finite.

Although Gröbner basis theory does not depend on a particular choice of an admissible monomial ordering, three monomial orderings are specially important for the applications:

- Lexicographical ordering, commonly called lex or plex (for pure lexical ordering).

- Total degree reverse lexicographical ordering, commonly called degrevlex.

- Elimination ordering, lexdeg.

Gröbner basis theory was initially introduced for the lexicographical ordering. It was soon realised that the Gröbner basis for degrevlex is almost always much easier to compute, and that it is almost always easier to compute a lex Gröbner basis by first computing the degrevlex basis and then using a "change of ordering algorithm". When elimination is needed, degrevlex is not convenient; both lex and lexdeg may be used but, again, many computations are relatively easy with lexdeg and almost impossible with lex.

Once a monomial ordering is fixed, the terms of a polynomial (product of a monomial with its nonzero coefficient) are naturally ordered by decreasing monomials (for this order). This makes the representation of a polynomial as an ordered list of pairs coefficient–exponent vector a canonical representation of the polynomials. The first (greatest) term of a polynomial p for this ordering and the corresponding monomial and coefficient are respectively called the leading term, leading monomial and leading coefficient and denoted, in this article, lt(p), lm(p) and lc(p).

Reduction

The concept of reduction, also called multivariate division or normal form computation, is central to Gröbner basis theory. It is a multivariate generalization of the Euclidean division of univariate polynomials.

In this section we suppose a fixed monomial ordering, which will not be defined explicitly.

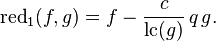

Given two polynomials f and g, one says that f is reducible by g if some monomial m in f is a multiple of the leading monomial lm(g) of g. If m happens to be the leading monomial of f then one says that f is lead-reducible by g. If c is the coefficient of m in f and m = q lm(g), the one-step reduction of f by g is the operation that associates to f the polynomial

The main properties of this operation are that the resulting polynomial does not contain the monomial m and that the monomials greater than m (for the monomial ordering) remain unchanged. This operation is not, in general, uniquely defined; if several monomials in f are multiples of lm(g) one may choose arbitrarily the one that is reduced. In practice, it is better to choose the greatest one for the monomial ordering, because otherwise subsequent reductions could reintroduce the monomial that has just been removed.

Given a finite set G of polynomials, one says that f is reducible or lead-reducible by G if it is reducible or lead-reducible, respectively, by an element of G. If it is the case, then one defines  . The (complete) reduction of f by G consists in applying iteratively this operator

. The (complete) reduction of f by G consists in applying iteratively this operator  until getting a polynomial

until getting a polynomial  , which is irreducible by G. It is called a normal form of f by G. In general this form is not uniquely defined (this is not a canonical form); this non-uniqueness is the starting point of Gröbner basis theory.

, which is irreducible by G. It is called a normal form of f by G. In general this form is not uniquely defined (this is not a canonical form); this non-uniqueness is the starting point of Gröbner basis theory.

For Gröbner basis computations, except at the end, it is not necessary to do a complete reduction: a lead-reduction is sufficient, which saves a large amount of computation.

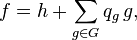

The definition of the reduction shows immediately that, if h is a normal form of f by G, then we have

where the  are polynomials. In the case of univariate polynomials, if G is reduced to a single element g, then h is the remainder of the Euclidean division of f by g, qg is the quotient and the division algorithm is exactly the process of lead-reduction. For this reason, some authors use the term multivariate division instead of reduction.

are polynomials. In the case of univariate polynomials, if G is reduced to a single element g, then h is the remainder of the Euclidean division of f by g, qg is the quotient and the division algorithm is exactly the process of lead-reduction. For this reason, some authors use the term multivariate division instead of reduction.

Formal definition

A Gröbner basis G of an ideal I in a polynomial ring R over a field is a generating set of I characterized by any one of the following properties, stated relatively to some monomial order:

- the ideal given by the leading terms of polynomials in I is itself generated by the leading terms of the basis G;

- the leading term of any polynomial in I is divisible by the leading term of some polynomial in the basis G;

- the multivariate division of any polynomial in the polynomial ring R by G gives a unique remainder;

- the multivariate division by G of any polynomial in the ideal I gives the remainder 0.

All these properties are equivalent; different authors use different definitions depending on the topic they choose. The last two properties allow calculations in the factor ring R/I with the same facility as modular arithmetic. It is a significant fact of commutative algebra that Gröbner bases always exist, and can be effectively obtained for any ideal starting with a generating subset.

Multivariate division requires a monomial ordering, the basis depends on the monomial ordering chosen, and different orderings can give rise to radically different Gröbner bases. Two of the most commonly used orderings are lexicographic ordering, and degree reverse lexicographic order (also called graded reverse lexicographic order or simply total degree order). Lexicographic order eliminates variables, however the resulting Gröbner bases are often very large and expensive to compute. Degree reverse lexicographic order typically provides for the fastest Gröbner basis computations. In this order monomials are compared first by total degree, with ties broken by taking the smallest monomial with respect to lexicographic ordering with the variables reversed.

In most cases (polynomials in finitely many variables with complex coefficients or, more generally, coefficients over any field, for example), Gröbner bases exist for any monomial ordering. Buchberger's algorithm is the oldest and most well-known method for computing them. Other methods are the Faugère's F4 and F5 algorithms, based on the same mathematics as the Buchberger algorithm, and involutive approaches, based on ideas from differential algebra.[3] There are also three algorithms for converting a Gröbner basis with respect to one monomial order to a Gröbner basis with respect to a different monomial order: the FGLM algorithm, the Hilbert Driven Algorithm and the Gröbner walk algorithm. These algorithms are often employed to compute (difficult) lexicographic Gröbner bases from (easier) total degree Gröbner bases.

A Gröbner basis is termed reduced if the leading coefficient of each element of the basis is 1 and no monomial in any element of the basis is in the ideal generated by the leading terms of the other elements of the basis. In the worst case, computation of a Gröbner basis may require time that is exponential or even doubly exponential in the number of solutions of the polynomial system (for degree reverse lexicographic order and lexicographic order, respectively). Despite these complexity bounds, both standard and reduced Gröbner bases are often computable in practice, and most computer algebra systems contain routines to do so.

The concept and algorithms of Gröbner bases have been generalized to submodules of free modules over a polynomial ring. In fact, if L is a free module over a ring R, then one may consider R⊕L as a ring by defining the product of two elements of L to be 0. This ring may be identified with ![R[e_1, \ldots, e_l]/\left\langle \{e_ie_j|1\le i\le j\le l\}\right\rangle,](../I/m/bfe7b4fffaae088b827376a48f32f02f.png) where

where  is a basis of L. This allows to identify a submodule of L generated by

is a basis of L. This allows to identify a submodule of L generated by  with the ideal of

with the ideal of ![R[e_1, \ldots, e_l]](../I/m/50153332f1fc9b0c4250f45c554a254f.png) generated by

generated by  and the products

and the products  ,

,  . If R is a polynomial ring, this reduces the theory and the algorithms of Gröbner bases of modules to the theory and the algorithms of Gröbner bases of ideals.

. If R is a polynomial ring, this reduces the theory and the algorithms of Gröbner bases of modules to the theory and the algorithms of Gröbner bases of ideals.

The concept and algorithms of Gröbner bases have also been generalized to ideals over various rings, commutative or not, like polynomial rings over a principal ideal ring or Weyl algebras.

Example and counterexample

Let R = Q[x,y] be the ring of bivariate polynomials with rational coefficients and consider the ideal I = <f,g> generated by the polynomials

- f(x,y) = x2 - y

- g(x,y) = x3 - x

Two other elements of I are the polynomials

- k(x,y) = -xf(x,y) + g(x,y) = xy - x

- h(x,y) = xk(x,y) − (y - 1)f(x,y) = y2 - y

Under lexicographic ordering with x > y we have

- lt(f) = x2

- lt(g) = x3

- lt(h) = y2

The ideal generated by {lt(f),lt(g)} only contains polynomials that are divisible by x2 which excludes lt(h) = y2; it follows that {f, g} is not a Gröbner basis for I.

On the other hand we can show that {f, k, h} is indeed a Gröbner basis for I.

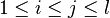

First note that f and g, and therefore also h, k and all the other polynomials in the ideal I have the following three zeroes in the (x,y) plane in common, as indicated in the figure: {(1,1),(-1,1),(0,0)}. Those three points are not collinear, so I does not contain any polynomial of the first degree. Neither can I contain any polynomials of the special form

- m(x,y) = cx + p(y)

with c a nonzero rational number and p a polynomial in the variable y only; the reason being that such an m can never have two distinct zeroes with the same value for y (in this case, the points (1,1) and (-1,1)).

From the above it follows that I, apart from the zero polynomial, only contains polynomials whose leading term has degree greater than or equal to 2; therefore their leading terms are divisible by at least one of the three monomials

- {x2, xy, y2} = {lt(f),lt(k),lt(h)}.

This means that {f, k, h} is a Gröbner basis for I with respect to lexicographic ordering with x > y.

Properties and applications of Gröbner bases

Unless explicitly stated, all the results that follow[4] are true for any monomial ordering (see that article for the definitions of the different orders that are mentioned below).

It is a common misconception to think that the lexicographical order is needed for some of these results. On the contrary, the lexicographical order is, almost always, the most difficult to compute, and using it makes unpractical many computations that are relatively easy with graded reverse lexicographic order (grevlex), or, when elimination is needed, the elimination order (lexdeg) which restricts to grevlex on each block of variables.

Equality of ideals

Reduced Gröbner bases are unique for any given ideal and any monomial ordering. Thus two ideals are equal if and only if they have the same (reduced) Gröbner basis (usually a Gröbner basis software always produces reduced Gröbner bases).

Membership and inclusion of ideals

The reduction of a polynomial f by the Gröbner basis G of an ideal I yields 0 if and only if f is in I. This allows to test the membership of an element in an ideal. Another method consists in verifying that the Gröbner basis of G∪{f} is equal to G.

To test if the ideal I generated by f1, ...,fk is contained in the ideal J, it suffices to test that every fi is in J. One may also test the equality of the reduced Gröbner bases of J and J∪{f1, ...,fk}.

Solutions of a system of algebraic equations

Any set of polynomials may be viewed as a system of polynomial equations by equating the polynomials to zero. The set of the solutions of such a system depends only on the generated ideal, and, therefore does not change when the given generating set is replaced by the Gröbner basis, for any ordering, of the generated ideal. Such a solution, with coordinates in an algebraically closed field containing the coefficients of the polynomials, is called a zero of the ideal. In the usual case of rational coefficients, this algebraically closed field is chosen as the complex field.

An ideal does not have any zero (the system of equations is inconsistent) if and only if 1 belongs to the ideal (this is Hilbert's Nullstellensatz), or, equivalently, if its Gröbner basis (for any monomial ordering) contains 1, or, also, if the corresponding reduced Gröbner basis is [1].

Given the Gröbner basis G of an ideal I, it has only a finite number of zeros, if and only if, for each variable x, G contains a polynomial with a leading monomial that is a power of x (without any other variable appearing in the leading term). If it is the case the number of zeros, counted with multiplicity, is equal to the number of monomials that are not multiple of any leading monomial of G. This number is called the degree of the ideal.

When the number of zeros is finite, the Gröbner basis for a lexicographical monomial ordering provides, theoretically a solution: the first coordinates of a solution is a root of the greatest common divisor of polynomials of the basis that depends only of the first variable. After substituting this root in the basis, the second coordinates of this solution is a root of the greatest common divisor of the resulting polynomials that depends only on this second variable, and so on. This solving process is only theoretical, because it implies GCD computation and root-finding of polynomials with approximate coefficients, which are not practicable because of numeric instability. Therefore, other methods have been developed to solve polynomial systems through Gröbner bases (see System of polynomial equations for more details).

Dimension, degree and Hilbert series

The dimension of an ideal I in a polynomial ring R is the Krull dimension of the ring R/I and is equal to the dimension of the algebraic set of the zeros of I. It is also equal to number of hyperplanes in general position which are needed to have an intersection with the algebraic set, which is a finite number of points. The degree of the ideal and of its associated algebraic set is the number of points of this finite intersection, counted with multiplicity. In particular, the degree of an hypersurface is equal to the degree of its definition polynomial.

Both degree and dimension depends only on the set of the leading monomials of the Gröbner basis of the ideal for any monomial ordering.

The dimension is the maximal size of a subset S of the variables such that there is no leading monomial depending only on the variables in S. Thus, if the ideal has dimension 0, then for each variable x there is a leading monomial in the Gröbner basis that is a power of x.

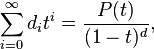

Both dimension and degree may be deduced from the Hilbert series of the ideal, which is the series  , where

, where  is the number of monomials of degree i that are not multiple of any leading monomial in the Gröbner basis. The Hilbert series may be summed into a rational fraction

is the number of monomials of degree i that are not multiple of any leading monomial in the Gröbner basis. The Hilbert series may be summed into a rational fraction

where d is the dimension of the ideal and  is a polynomial such that

is a polynomial such that  is the degree of the ideal.

is the degree of the ideal.

Although the dimension and the degree do not depend on the choice of the monomial ordering, the Hilbert series and the polynomial  change when one changes of monomial ordering.

change when one changes of monomial ordering.

Most computer algebra systems that provide functions to compute Gröbner bases provide also functions for computing the Hilbert series, and thus also the dimension and the degree.

Elimination

The computation of Gröbner bases for an elimination monomial ordering allows computational elimination theory. This is based on the following theorem.

Let us consider a polynomial ring ![K[x_1,\ldots,x_n,y_1,\ldots,y_m]=K[X,Y],](../I/m/0f79c1ff41e09f2989ad1fdba5d6b6b5.png) in which the variables are split into two subsets X and Y. Let us also choose an elimination monomial ordering "eliminating" X, that is a monomial ordering for which two monomials are compared by comparing first the X-parts, and, in case of equality only, considering the Y-parts. This implies that a monomial containing an X-variable is greater than every monomial independent of X.

If G is a Gröbner basis of an ideal I for this monomial ordering, then

in which the variables are split into two subsets X and Y. Let us also choose an elimination monomial ordering "eliminating" X, that is a monomial ordering for which two monomials are compared by comparing first the X-parts, and, in case of equality only, considering the Y-parts. This implies that a monomial containing an X-variable is greater than every monomial independent of X.

If G is a Gröbner basis of an ideal I for this monomial ordering, then ![G\cap K[Y]](../I/m/91e3cd97d08bedec5f168bf8057faadd.png) is a Gröbner basis of

is a Gröbner basis of ![I\cap K[Y]](../I/m/ebaabc52f7f8f50074b381748ae630a9.png) (this ideal is often called the elimination ideal). Moreover, a polynomial belongs to

(this ideal is often called the elimination ideal). Moreover, a polynomial belongs to ![G\cap K[Y]](../I/m/91e3cd97d08bedec5f168bf8057faadd.png) if and only if its leading term belongs to

if and only if its leading term belongs to ![G\cap K[Y]](../I/m/91e3cd97d08bedec5f168bf8057faadd.png) (this makes very easy the computation of

(this makes very easy the computation of ![G\cap K[Y]](../I/m/91e3cd97d08bedec5f168bf8057faadd.png) , as only the leading monomials need to be checked).

, as only the leading monomials need to be checked).

This elimination property has many applications, some of them are reported in the next sections.

Another application, in algebraic geometry, is that elimination realizes the geometric operation of projection of an affine algebraic set into a subspace of the ambient space: with above notation, the (Zariski closure of) the projection of the algebraic set defined by the ideal I into the Y-subspace is defined by the ideal ![I\cap K[Y].](../I/m/0bcb57347d875cf79605789c9c8aad68.png)

The lexicographical ordering such that  is an elimination ordering for every partition

is an elimination ordering for every partition  Thus a Gröbner basis for this ordering carries much more information than usually necessary. This may explain why Gröbner bases for the lexicographical ordering are usually the most difficult to compute.

Thus a Gröbner basis for this ordering carries much more information than usually necessary. This may explain why Gröbner bases for the lexicographical ordering are usually the most difficult to compute.

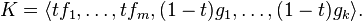

Intersecting ideals

If I and J are two ideals generated respectively by {f1, ..., fm} and {g1, ..., gk}, then a single Gröbner basis computation produces a Gröbner basis of their intersection I ∩ J. For this, one introduces a new indeterminate t, and one uses an elimination ordering such that the first block contains only t and the other block contains all the other variables (this means that a monomial containing t is greater than every monomial that do not contain t. With this monomial ordering, a Gröbner basis of I ∩ J consists in the polynomials that do not contain t, in the Gröbner basis of the ideal

In other words, I ∩ J is obtained by eliminating t in K.

This may be proven by remarking that the ideal K consists in the polynomials  such that

such that  and

and  . Such a polynomial is independent of t if and only a=b, which means that

. Such a polynomial is independent of t if and only a=b, which means that

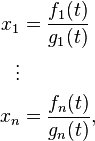

Implicitization of a rational curve

A rational curve is an algebraic curve that has a parametric equation of the form

where  and

and  are univariate polynomials for 1 ≤ i ≤ n. One may (and will) suppose that

are univariate polynomials for 1 ≤ i ≤ n. One may (and will) suppose that  and

and  are coprime (they have no non-constant common factors).

are coprime (they have no non-constant common factors).

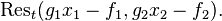

Implicitization consists in computing the implicit equations of such a curve. In case of n = 2, that is for plane curves, this may be computed with the resultant. The implicit equation is the following resultant:

Elimination with Gröbner bases allow to implicitize for any value of n, simply by eliminating t in the ideal

If n = 2, the result is the same as with the resultant, if the map

If n = 2, the result is the same as with the resultant, if the map  is injective for almost every t. In the other case, the resultant is a power of the result of the elimination.

is injective for almost every t. In the other case, the resultant is a power of the result of the elimination.

Saturation

When modeling a problem by polynomial equations, it is highly frequent that some quantities are supposed to be non zero, because, if they are zero, the problem becomes very different. For example, when dealing with triangles, many properties become false if the triangle is degenerated, that is if the length of one side is equal to the sum of the lengths of the other sides. In such situations, there is no hope to deduce relevant information from the polynomial system if the degenerate solutions are not dropped out. More precisely, the system of equations defines an algebraic set which may have several irreducible components, and one has to remove the components on which the degeneracy conditions are everywhere zero.

This is done by saturating the equations by the degeneracy conditions, which may be done by using the elimination property of Gröbner bases.

Definition of the saturation

The localization of a ring consists in adjoining to it the formal inverses of some elements. This section concerns only the case of a single element, or equivalently a finite number of elements (adjoining the inverses of several elements is equivalent to adjoin the inverse of their product. The localization of a ring R by an element f is the ring ![R_f=R[t]/(1-ft),](../I/m/98393cba195e543d42ecb6eda4d67b70.png) where t is a new indeterminate representing the inverse of f. The localization of an ideal I of R is the ideal

where t is a new indeterminate representing the inverse of f. The localization of an ideal I of R is the ideal  of

of  When R is a polynomial ring, computing in

When R is a polynomial ring, computing in  is not efficient, because of the need to manage the denominators. Therefore, the operation of localization is usually replaced by the operation of saturation.

is not efficient, because of the need to manage the denominators. Therefore, the operation of localization is usually replaced by the operation of saturation.

The saturation with respect to f of an ideal I in R is the inverse image of  under the canonical map from R to

under the canonical map from R to  It is the ideal

It is the ideal  consisting in all elements of R whose products by some power of f belongs to I.

consisting in all elements of R whose products by some power of f belongs to I.

If J is the ideal generated by I and 1-ft in R[t], then  It follows that, if R is a polynomial ring, a Gröbner basis computation eliminating t allows to compute a Gröbner basis of the saturation of an ideal by a polynomial.

It follows that, if R is a polynomial ring, a Gröbner basis computation eliminating t allows to compute a Gröbner basis of the saturation of an ideal by a polynomial.

The important property of the saturation, which ensures that it removes from the algebraic set defined by the ideal I the irreducible components on which the polynomial f is zero is the following: The primary decomposition of  consists in the components of the primary decomposition of I that do not contain any power of f.

consists in the components of the primary decomposition of I that do not contain any power of f.

Computation of the saturation

A Gröbner basis of the saturation by f of a polynomial ideal generated by a finite set of polynomials F, may be obtained by eliminating t in  that is by keeping the polynomials independent of t in the Gröbner basis of

that is by keeping the polynomials independent of t in the Gröbner basis of  for an elimination ordering eliminating t.

for an elimination ordering eliminating t.

Instead of using F, one may also start from a Gröbner basis of F. It depends on the problems, which method is most efficient. However, if the saturation does not remove any component, that is if the ideal is equal to its saturated ideal, computing first the Gröbner basis of F is usually faster. On the other hand if the saturation removes some components, the direct computation may be dramatically faster.

If one wants to saturate with respect to several polynomials  or with respect to a single polynomial which is a product

or with respect to a single polynomial which is a product  there are three ways to proceed, that give the same result but may have very different computation times (it depends on the problem which is the most efficient).

there are three ways to proceed, that give the same result but may have very different computation times (it depends on the problem which is the most efficient).

- Saturating by

in a single Gröbner basis computation.

in a single Gröbner basis computation. - Saturating by

then saturating the result by

then saturating the result by  and so on.

and so on. - Adding to F or to its Gröbner basis the polynomials

and eliminating the

and eliminating the  in a single Gröbner basis computation.

in a single Gröbner basis computation.

Effective Nullstellensatz

Hilbert's Nullstellensatz has two versions. The first one asserts that a set of polynomials has an empty set of common zeros in an algebraic closure of the field of the coefficients if and only if 1 belongs to the generated ideal. This is easily tested with a Gröbner basis computation, because 1 belongs to an ideal if and only if 1 belongs to the Gröbner basis of the ideal, for any monomial ordering.

The second version asserts that the set of common zeros (in an algebraic closure of the field of the coefficients) of an ideal is contained in the hypersurface of the zeros of a polynomial f, if and only if a power of f belongs to the ideal. This may be tested by a saturating the ideal by f; in fact, a power of f belongs to the ideal if and only if the saturation by f provides a Gröbner basis containing 1.

Implicitization in higher dimension

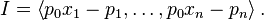

By definition, an affine rational variety of dimension k may be described by parametric equations of the form

where  are n+1 polynomials in the k variables (parameters of the parameterization)

are n+1 polynomials in the k variables (parameters of the parameterization)  Thus the parameters

Thus the parameters  and the coordinates

and the coordinates  of the points of the variety are zeros of the ideal

of the points of the variety are zeros of the ideal

One could guess that it suffices to eliminate the parameters to obtain the implicit equations of the variety, as it has been done in the case of curves. Unfortunately this is not always the case. If the  have a common zero (sometimes called base point), every irreducible component of the non-empty algebraic set defined by the

have a common zero (sometimes called base point), every irreducible component of the non-empty algebraic set defined by the  is an irreducible component of the algebraic set defined by I. It follows that, in this case, the direct elimination of the

is an irreducible component of the algebraic set defined by I. It follows that, in this case, the direct elimination of the  provides an empty set of polynomials.

provides an empty set of polynomials.

Therefore, if k>1, two Gröbner basis computations are needed to implicitize:

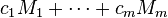

- Saturate

by

by  to get a Gröbner basis

to get a Gröbner basis

- Eliminate the

from

from  to get a Gröbner basis of the ideal (of the implicit equations) of the variety.

to get a Gröbner basis of the ideal (of the implicit equations) of the variety.

Implementations

- CoCoA free computer algebra system for computing Gröbner bases.

- GAP free computer algebra system that can perform Gröbner bases calculations.

- FGb, Faugère's own implementation of his F4 algorithm, available as a Maple library.[5] To the date, as of 2014, it is, with Magma, the fastest implementation for rational coefficients and coefficients in a finite field of prime order.

- Macaulay 2 free software for doing polynomial computations, particularly Gröbner bases calculations.

- Magma has a very fast implementation of the Faugère's F4 algorithm.[6]

- Maple has implementations of the Buchberger and Faugère F4 algorithms, as well as Gröbner trace.

- Mathematica includes an implementation of the Buchberger algorithm, with performance-improving techniques such as the Gröbner walk, Gröbner trace, and an improvement for toric bases.

- SINGULAR free software for computing Gröbner bases.

- Sage provides a unified interface to several computer algebra systems (including SINGULAR and Macaulay), and includes a few Gröbner basis algorithms of its own.

- SymPy Python computer algebra system uses Gröbner bases to solve polynomial systems.

See also

- Buchberger's algorithm

- Faugère's F4 and F5 algorithms

- Graver basis

- Gröbner–Shirshov basis

- Regular chains, an alternative way to represent algebraic sets

References

- ↑ Lazard, D. (1983). "Gröbner bases, Gaussian elimination and resolution of systems of algebraic equations". Computer Algebra. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 162. pp. 146–156. doi:10.1007/3-540-12868-9_99. ISBN 978-3-540-12868-7.

- ↑ Bodo Renschuch, Hartmut Roloff, Georgij G. Rasputin et. al. (2003). Contributions to Constructive Polynomial Ideal Theory XXIII: Forgotten Works of Leningrad Mathematician N. M. Gjunter on Polynomial Ideal Theory. ACM SIGSAM Bulletin, Vol 37, No 2, (2003): 35–48. English translation by Michael Abramson.

- ↑ Vladimir P. Gerdt, Yuri A. Blinkov (1998). Involutive Bases of Polynomial Ideals, Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 45:519ff

- ↑ David Cox, John Little, and Donal O'Shea (1997). Ideals, Varieties, and Algorithms: An Introduction to Computational Algebraic Geometry and Commutative Algebra. Springer. ISBN 0-387-94680-2.

- ↑ FGb home page

- ↑ Allan Steel's Gröbner Basis Timings Page

Further reading

- William W. Adams, Philippe Loustaunau (1994). An Introduction to Gröbner Bases. American Mathematical Society, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, Volume 3. ISBN 0-8218-3804-0

- Huishi Li (2011). Gröbner Bases in Ring Theory. World Scientific Publishing, ISBN 978-981-4365-13-0

- Thomas Becker, Volker Weispfenning (1998). Gröbner Bases. Springer Graduate Texts in Mathematics 141. ISBN 0-387-97971-9

- Bruno Buchberger (1965). An Algorithm for Finding the Basis Elements of the Residue Class Ring of a Zero Dimensional Polynomial Ideal. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Innsbruck. English translation by Michael Abramson in Journal of Symbolic Computation 41 (2006): 471–511. [This is Buchberger's thesis inventing Gröbner bases.]

- Bruno Buchberger (1970). An Algorithmic Criterion for the Solvability of a System of Algebraic Equations. Aequationes Mathematicae 4 (1970): 374–383. English translation by Michael Abramson and Robert Lumbert in Gröbner Bases and Applications (B. Buchberger, F. Winkler, eds.). London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series 251, Cambridge University Press, 1998, 535–545. ISBN 0-521-63298-6 (This is the journal publication of Buchberger's thesis.)

- Buchberger, Bruno; Kauers, Manuel (2010). "Gröbner Bases". Scholarpedia (5): 7763. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.7763.

- Ralf Fröberg (1997). An Introduction to Gröbner Bases. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-97442-0.

- Sturmfels, Bernd (November 2005), "What is . . . a Gröbner Basis?" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society 52 (10): 1199–1200, a brief introduction.

- A. I. Shirshov (1999). "Certain algorithmic problems for Lie algebras" (PDF). ACM SIGSAM Bulletin 33 (2): 3–6. doi:10.1145/334714.334715. (translated from Sibirsk. Mat. Zh. Siberian Mathematics Journal, 3 (1962), 292–296)

- M. Aschenbrenner and C. Hillar, Finite generation of symmetric ideals, Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 359 (2007), 5171–5192 (on infinite dimensional Gröbner bases for polynomial rings in infinitely many indeterminates).

External links

- Faugère's own implementation of his F4 algorithm

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Gröbner basis", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- B. Buchberger, Groebner Bases: A Short Introduction for Systems Theorists in Proceedings of EUROCAST 2001.

- Buchberger, B. and Zapletal, A. Gröbner Bases Bibliography.

- Comparative Timings Page for Gröbner Bases Software

- Prof. Bruno Buchberger Bruno Buchberger

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Gröbner Basis", MathWorld.

- Gröbner basis introduction on Scholarpedia

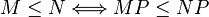

![\langle f_1,\ldots, f_k\rangle = \left\{\sum_{i=1}^k g_i f_i\;|\; g_1,\ldots, g_k\in K[x_1,\ldots,x_n]\right\}.](../I/m/8dbeb04743c318f167dc5ad9ceb5c96b.png)