Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution (Greek: Ελληνική Επανάσταση, Elliniki Epanastasi; Ottoman: يونان عصياني Yunan İsyanı Greek Uprising), was a successful war of independence waged by the Greek revolutionaries between 1821 and 1832 against the Ottoman Empire. The Greeks were later assisted by the Russian Empire, Great Britain, Bourbon France, and several other European powers, while the Ottomans were aided by their vassals, the Eyalets of Egypt, Algeria, Tripolitania, and the Beylik of Tunis.

Even several decades before the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, most of Greece had come under Ottoman rule.[4] During this time, there were several revolt attempts by Greeks to gain independence from Ottoman control.[5] In 1814, a secret organization called the Filiki Eteria was founded with the aim of liberating Greece. The Filiki Eteria planned to launch revolts in the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities, and in Constantinople and its surrounding areas. The first of these revolts began on 6 March 1821 in the Danubian Principalities, but was soon put down by the Ottomans. The events in the north urged the Greeks in the Peloponnese into action and on 17 March 1821, the Maniots declared war on the Ottomans. This declaration was the start of a spring of revolutionary actions from other controlled states against the Ottoman Empire.

By the end of the month, the Peloponnese was in open revolt against the Turks and by October 1821, the Greeks under Theodoros Kolokotronis had captured Tripolitsa. The Peloponnesian revolt was quickly followed by revolts in Crete, Macedonia, and Central Greece, which would soon be suppressed. Meanwhile, the makeshift Greek navy was achieving success against the Ottoman navy in the Aegean Sea and prevented Ottoman reinforcements from arriving by sea.

Tensions soon developed among different Greek factions, leading to two consecutive civil wars. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Sultan negotiated with Mehmet Ali of Egypt, who agreed to send his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece with an army to suppress the revolt in return for territorial gain. Ibrahim landed in the Peloponnese in February 1825 and had immediate success: by the end of 1825, most of the Peloponnese was under Egyptian control, and the city of Missolonghi—put under siege by the Turks since April 1825—fell in April 1826. Although Ibrahim was defeated in Mani, he had succeeded in suppressing most of the revolt in the Peloponnese and Athens had been retaken.

Following years of negotiation, three Great Powers, Russia, Britain and France, decided to intervene in the conflict and each nation sent a navy to Greece. Following news that combined Ottoman–Egyptian fleets were going to attack the Greek island of Hydra, the allied fleet intercepted the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet at Navarino. The battle began after a tense week-long standoff, ending in the destruction of the Ottoman–Egyptian fleet. With the help of a French expeditionary force, the Greeks drove the Turks out of the Peloponnese and proceeded to the Ottoman controlled part of central Greece by 1828. As a result of years of negotiation, Greece was finally recognized as an independent nation in the Treaty of Constantinople of May 1832.

The Revolution is celebrated by the modern Greek state as a national day on 25 March.

Background

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Greece |

|

|

History by topic |

| Greece portal |

Ottoman rule

The Fall of Constantinople on 29 May 1453 and the subsequent fall of the successor states of the Byzantine Empire marked the end of Byzantine sovereignty. After that, the Ottoman Empire ruled the Balkans and Anatolia, with some exceptions.i[›] Orthodox Christians were granted some political rights under Ottoman rule, but they were considered inferior subjects.[6] The majority of Greeks were called Rayah by the Turks, a name that referred to the large mass of non-Muslim subjects in the Ottoman ruling class.ii[›][7]

Meanwhile, Greek intellectuals and humanists, who had migrated west before or during the Ottoman invasions, such as Demetrios Chalkokondyles and Leonardos Philaras, began to call for the liberation of their homeland.[8] Demetrius Chalcondyles called on Venice and "all of the Latins" to aid the Greeks against "the abominable, monstrous, and impious barbarian Turks".[9] However, Greece was to remain under Ottoman rule for several more centuries.

The Greek Revolution was not an isolated event; numerous failed attempts at regaining independence took place throughout the history of the Ottoman era. Throughout the 17th century there was great resistance to the Ottomans in the Morea and elsewhere, as evidenced by revolts led by Dionysius the Philosopher.[10] After the Morean War, the Peloponnese came under Venetian rule for 30 years, and remained in turmoil from then on and throughout the 17th century, as the bands of klephts multiplied.[11]

The first great uprising was the Russian-sponsored Orlov Revolt of the 1770s, which was crushed by the Ottomans after having limited success. After the crushing of the uprising, Muslim Albanians ravaged many regions in mainland Greece.[12] However, the Maniots continually resisted Ottoman rule, and defeated several Ottoman incursions into their region, the most famous of which was the invasion of 1770.[13] During the Second Russo-Turkish War, the Greek community of Trieste financed a small fleet under Lambros Katsonis, which was a nuisance for the Ottoman navy; during the war klephts and armatoloi rose once again.[14]

At the same time, a number of Greeks enjoyed a privileged position in the Ottoman state as members of the Ottoman bureaucracy. Greeks controlled the affairs of the Orthodox Church through the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, as the higher clergy of the Orthodox Church was mostly of Greek origin. Thus, as a result of the Ottoman millet system, the predominantly Greek hierarchy of the Patriarchate enjoyed control over the Empire's Orthodox subjects (the Rum milleti[15]).[6]

The Greek Orthodox Church played a pivotal role in the preservation of national identity, the development of Greek society and the resurgence of Greek nationalism.iii[›] From the 18th century and onwards, members of prominent Greek families in Constantinople, known as Phanariotes (after the Phanar district of the city) gained considerable control over Ottoman foreign policy and eventually over the bureaucracy as a whole.[16]

Klephts and armatoloi

In times of militarily weak central authority, the Balkan countryside became infested by groups of bandits that struck at Muslims and Christians alike, called "klephts" (κλέφτες) in Greece, the equivalent of the hajduks. Defying Ottoman rule, the klephts were highly admired and held a significant place in popular lore.[17]

Responding to the klephts' attacks, the Ottomans recruited the ablest amongst these groups, contracting Christian militias, known as "armatoloi" (αρματολοί), to secure endangered areas, especially mountain passes.iv[›] The area under their control was called an "armatolik",[18] the oldest known being established in Agrafa during the reign of Murad II (r. 1421–1451).[19] The distinction between klephts and armatoloi was not clear, as the latter would often turn into klephts to extort more benefits from the authorities, while, conversely, another klepht group would be appointed to the armatolik to confront their predecessors.[20]

Nevertheless, klephts and armatoloi formed a provincial elite, though not a social class, whose members would muster under a common goal.[21] As the armatoloi's position gradually turned into a hereditary one, some captains took care of their armatolik as their personal property. A great deal of power was placed in their hands and they integrated in the network of clientelist relationships that formed the Ottoman administration.[20] Some managed to establish exclusive control in their armatolik, forcing the Porte to try repeatedly, though unsuccessfully, to eliminate them.[22]

By the time of the War of Independence powerful armatoloi could be traced in Rumeli, Thessaly, Epirus and southern Macedonia.[23] To the revolutionary leader and writer Yannis Makriyannis, klephts and armatoloi—being the only available major military force on the side of the Greeks—played such a crucial role in the Greek revolution that he referred to them as the "yeast of liberty".[24]

Enlightenment and the Greek national movement

Due to economic developments taking place both within and outside the Ottoman Empire, the 18th century witnessed the ascent of two merchant groups to prosperity: Greek sailors of several Aegean islands, such as Hydra and Andros, became affluent maritime merchants and Rumeli muleteers of Slav, Greek and predominantly Vlach origins changed from muleteers and peddlers to independent merchants and bankers after the treaty of Passarowitz. As commerce expanded in the Balkans, Greek became the area's 'lingua franca' and continental merchants homogenized through a process of assimilation to the Greek 'high culture' by the end of the century.[25]

They generated the wealth necessary to found schools, libraries and pay for young Greeks to study at the universities of Western Europe.[26] It was there that they came into contact with the radical ideas of the European Enlightenment, the French Revolution and romantic nationalism.[27] Educated and influential members of the large Greek diaspora, such as Adamantios Korais and Anthimos Gazis, tried to transmit these ideas back to the Greeks, with the double aim of raising their educational level and simultaneously strengthening their national identity. This was achieved through the dissemination of books, pamphlets and other writings in Greek, in a process that has been described as the modern Greek Enlightenment (Greek: Διαφωτισμός).[27]

In the 18th and 19th century, as revolutionary nationalism grew across Europe—including the Balkans (due, in large part, to the influence of the French Revolution[28])—the Ottoman Empire's power declined and Greek nationalism began to assert itself.[29]

The most influential of the Greek writers and intellectuals was Rigas Feraios. Deeply influenced by the French Revolution, Rigas was the first who conceived and organized a comprehensive national movement aiming at the liberation of all Balkan nations—including the Turks of the region—and the creation of a "Balkan Republic". Arrested by Austrian officials in Trieste in 1797, he was handed over to Ottoman officials and transported to Belgrade along with his co-conspirators. All of them were strangled to death and their bodies were dumped in the Danube, in June 1798.[30]

|

| Rigas Feraios, approx. translation from his 'Thourios' poem.[31] |

Rigas' death ultimately fanned the flames of Greek nationalism; his nationalist poem, the Thourios (war-song), was translated into a number of Western European and later Balkan languages and served as a rallying cry for Greeks against Ottoman rule.[28]

Another influential Greek writer and intellectual was Adamantios Korais who witnessed the French Revolution. Korais’ primary intellectual inspiration was from the Enlightenment and he borrowed ideas from Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. When Korais was a young adult he moved to Paris to continue his studies. He eventually graduated from the Montpellier School of Medicine and spent the remainder of his life in Paris. He would often have political and philosophical debates with Thomas Jefferson. While in Paris he was a witness to the French Revolution and saw the democracy that came out of it. He spent a lot of his time convincing wealthy Greeks to build schools and libraries to further the education of Greeks. He believed that a furthering in education would be necessary for the general welfare and prosperity of the people of Greece, as well as the country. Korais’ ultimate goal was a democratic Greece much like the Golden Age of Pericles but he died before the end of the revolution.

The Greek cause began to draw support not only from the large Greek merchant diaspora in both Western Europe and Russia, but also from Western European Philhellenes.[29] This Greek movement for independence was not only the first movement of national character in Eastern Europe, but also the first one in a non-Christian environment, like the Ottoman Empire.[32]

Filiki Eteria

Feraios' martyrdom was to inspire three young Greek merchants: Nikolaos Skoufas, Emmanuil Xanthos, and Athanasios Tsakalov. Influenced by the Italian Carbonari and profiting from their own experience as members of Freemasonic organizations, they founded in 1814 the secret Filiki Eteria ("Friendly Society") in Odessa, an important center of the Greek mercantile diaspora.[33] With the support of wealthy Greek exile communities in Britain and the United States and with the aid of sympathizers in Western Europe, they planned the rebellion.[34]

The society's basic objective was a revival of the Byzantine Empire, with Constantinople as the capital, not the formation of a national state.[34] In early 1820, Ioannis Kapodistrias, an official from the Ionian Islands who had become the joint foreign minister of Tsar Alexander I, was approached by the Society in order to be named leader but declined the offer; the Filikoi (members of Filiki Eteria) then turned to Alexander Ypsilantis, a Phanariote serving in the Russian army as general and adjutant to Alexander, who accepted.[35]

The Filiki Eteria expanded rapidly and was soon able to recruit members in all areas of the Greek world and among all elements of the Greek society.v[›] In 1821, the Ottoman Empire mainly faced war against Persia and more particularly the revolt by Ali Pasha in Epirus, which had forced the vali (governor) of the Morea, Hursid Pasha, and other local pashas to leave their provinces and campaign against the rebel force. At the same time, the Great Powers, allied in the "Concert of Europe" in opposition to revolutions in the aftermath of Napoleon I of France, were preoccupied with revolts in Italy and Spain. It was in this context that the Greeks judged the time ripe for their own revolt. The plan originally involved uprisings in three places, the Peloponnese, the Danubian Principalities and Constantinople.[36]

Philhellenism

Because of the Greek origin of so much of the West's classical heritage, there was tremendous sympathy for the Greek cause throughout Europe. Many wealthy Americans and Western European aristocrats, such as the renowned poet Lord Byron and later the physician Samuel Howe, took up arms to join the Greek revolutionaries.[37]

Many more also financed the revolution. The London Philhellenic Committee helped insurgent Greece to float two loans in 1824 (£800,000) and 1825 (£2,000,000).[38] The Scottish historian and philhellene Thomas Gordon took part in the revolutionary struggle and later wrote the first histories of the Greek revolution in English. According to Albert Boime, "The philhellenes willingly overlooked many of the contradictory stories about Greek atrocities, because they had nowhere else to deposit their libertarian impulses."[39]

|

The mountains look on Marathon --

|

| Byron, The Isles of Greece[40] |

In Europe, the Greek revolt aroused widespread sympathy among the public, although at first it was met with lukewarm and negative reception from the Great Powers. Some historians argue that Ottoman atrocities were given wide coverage in Europe, while Christian atrocities tended to be suppressed or played down.[41] The Ottoman massacres at Chios in 1822 inspired Eugène Delacroix's famous painting Massacre of Chios; other philhellenic works by Delacroix were inspired by various Byron poems. Byron, the most celebrated philhellene of all, lent his name, prestige and wealth to the cause.[42]

Byron spent time in Albania and Greece, organizing funds and supplies (including the provision of several ships), but died from fever at Missolonghi in 1824. Byron's death helped to create an even stronger European sympathy for the Greek cause. His poetry, along with Delacroix's art, helped arouse European public opinion in favor of the Greek revolutionaries to the point of no return, and led Western powers to intervene directly.[43]

Philhellenism made a notable contribution to romanticism, enabling the younger generation of artistic and literary intellectuals to expand the classical repertoire by treating modern Greek history as an extension of ancient history; the idea of a regeneration of the spirit of ancient Greece permeated the rhetoric of the Greek cause's supporters. Classicists and romantics of that period envisioned the casting out of the Turks as the prelude to the revival of the Golden Age.[44]

Outbreak of the revolution

Danubian principalities

Alexander Ypsilantis was elected as the head of the Filiki Eteria in April 1820 and took upon him the task of planning the insurrection. Ypsilantis' intention was to raise all the Christians of the Balkans in rebellion and perhaps force Russia to intervene on their behalf. On 22 February [N.S. 6 March], he crossed the river Prut with his followers, entering the Danubian Principalities.[45] In order to encourage the local Romanian Christians to join him, he announced that he had "the support of a Great Power", implying Russia. Two days after crossing the Prut, at Three Holy Hierarchs Monastery in Iaşi (Jassy), the capital of Moldavia, Ypsilantis issued a proclamation calling all Greeks and Christians to rise up against the Ottomans.[45][46][47] Michael Soutzos, then Prince of Moldavia and a member of Filiki Etaireia, set his guard at Ypsilantis' disposal. In the meanwhile, Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople and the Synod had anathematized and excommunicated both Ypsilantis and Soutzos issuing many encyclicals, an explicit denunciation of the Revolution in line with the Orthodox Church's policy.[48]

| "Fight for Faith and Fatherland! The time has come, O Hellenes. Long ago the people of Europe, fighting for their own rights and liberties, invited us to imitation ... The enlightened peoples of Europe are occupied in restoring the same well-being, and, full of gratitude for the benefactions of our forefathers towards them, desire the liberation of Greece. We, seemingly worthy of ancestral virtue and of the present century, are hopeful that we will achieve their defense and help. Many of these freedom-lovers want to come and fight alongside us ... Who then hinders your manly arms? Our cowardly enemy is sick and weak. Our generals are experienced, and all our fellow countrymen are full of enthusiasm. Unite, then, O brave and magnanimous Greeks! Let national phalanxes be formed, let patriotic legions appear and you will see those old giants of despotism fall themselves, before our triumphant banners." |

| Ypsilantis' Proclamation at Iaşi.[49] |

Instead of directly advancing on Brăila, where he arguably could have prevented Ottoman armies from entering the Principalities, and where he might have forced Russia to accept a fait accompli, Ypsilantis remained in Iaşi, and ordered the executions of several pro-Ottoman Moldavians. In Bucharest, where he had arrived in early April after some weeks delay, he decided that he could not rely on the Wallachian Pandurs to continue their Oltenian-based revolt and assist the Greek cause. The Pandur leader was Tudor Vladimirescu, who had already reached the outskirts of Bucharest on 16 March [N.S. 28 March]. In Bucharest, the relations of the two men deteriorated dramatically; Vladimirescu's first priority was to assert his authority against the newly appointed prince Scarlat Callimachi, trying to maintain relations with both Russia and the Ottomans.[50]

At that point, Kapodistrias, the foreign minister of Russia, was ordered by Alexander I to send Ypsilantis a letter upbraiding him for misusing the mandate received from the Tsar; Kapodistrias announced to Ypsilantis that his name had been struck off the army list and that he was commanded to lay down arms. Ypsilantis tried to ignore the letter, but Vladimirescu took this as the end of his commitment to the Eteria. A conflict erupted inside his camp and he was tried and put to death by the Eteria on 26 May [N.S. 7 June]. The loss of their Romanian allies, followed by an Ottoman intervention on Wallachian soil, sealed defeat for the Greek exiles and culminated in the disastrous Battle of Dragashani and the destruction of the Sacred Band on 7 June [N.S. 19 June].[51]

.svg.png)

Alexander Ypsilantis, accompanied by his brother Nicholas and a remnant of his followers, retreated to Râmnicu Vâlcea, where he spent some days negotiating with the Austrian authorities for permission to cross the frontier. Fearing that his followers might surrender him to the Turks, he gave out that Austria had declared war on Turkey, caused a Te Deum to be sung in Cozia Monastery, and, on pretext of arranging measures with the Austrian commander-in-chief, he crossed the frontier. However, the reactionary policies of the Holy Alliance were enforced by Francis II and the country refused to give asylum for leaders of revolts in neighboring countries. Ypsilantis was kept in close confinement for seven years.[52] In Moldavia, the struggle continued for a while, under Giorgakis Olympios and Yiannis Pharmakis but, by the end of the year, the provinces had been pacified by the Ottomans.

The outbreak of the war was met by mass executions, pogrom-style attacks, the destruction of churches, and looting of Greek properties throughout the Empire. The most severe atrocities occurred in Constantinople, in what became known as the Constantinople Massacre of 1821. The Orthodox Patriarch Gregory V was executed on April 22, 1821 on the orders of the Sultan despite his opposition to the revolt, which caused outrage throughout Europe and resulted in increased support for the Greek rebels.[53]

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese, with its long tradition of resistance to the Ottomans, was to become the heartland of the revolt. In the early months of 1821, with the absence of the Ottoman governor of the Morea Mora valisi Hursid Pasha and many of his troops, the situation was favourable for the Greeks to rise against Ottoman occupation. The crucial meeting was held at Vostitsa (modern Aigion), where chieftains and prelates from all over the Peloponnese assembled on 26 January. There, Papaflessas, a pro-revolution priest who presented himself as representative of Filiki Eteria clashed with most of the civil leaders and members of the senior clergy, such as Metropolitan Germanos of Patras, who were sceptical and demanded guarantees about a Russian intervention.[54] As news came of Ypsilantis' march into the Danubian Principalities, the atmosphere in the Peloponnese was tense, and by mid-March, sporadic incidents against Muslims occurred, heralding the start of the uprising. According to the tradition, the Revolution was declared on 25 March 1821 (N.S. 6 April) by Metropolitan Germanos who raised the banner with the cross in the Monastery of Agia Lavra, although some historians question the historicity of the event.[55]

On 17 March 1821, war was declared on the Turks by the Maniots in Areopoli. The same day, a force of 2,000 Maniots under the command of Petros Mavromichalis advanced on the Messenian town of Kalamata, where they united with troops under Theodoros Kolokotronis, Nikitaras and Papaflessas; Kalamata fell to the Greeks on 23 March.[56] In Achaia, the town of Kalavryta was besieged on 21 March, and in Patras conflicts lasted for many days. The Ottomans launched sporadic attacks towards the city while the revolutionaries, led by Panagiotis Karatzas, drove them back to the fortress.[57]

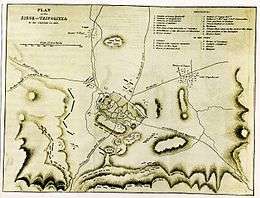

By the end of March, the Greeks effectively controlled the countryside, while the Turks were confined to the fortresses, most notably those of Patras (recaptured by the Turks on 3 April by Yussuf Pasha), Rio, Acrocorinth, Monemvasia, Nafplion and the provincial capital, Tripolitsa, where many Muslims had fled with their families at the beginning of the uprising. All these were loosely besieged by local irregular forces under their own captains, since the Greeks lacked artillery. With the exception of Tripolitsa, all sites had access to the sea and could be resupplied and reinforced by the Ottoman fleet. Since May, Kolokotronis organized the siege of Tripolitsa, and, in the meantime, Greek forces twice defeated the Turks, who unsuccessfully tried to repulse the besiegers. Finally, Tripolitsa was seized by the Greeks on 23 September [N.S. 5 October],[58] and the city was given over to the mob for two days.[59] After lengthy negotiations, the Turkish forces surrendered Actrocorinth on 14 January 1822.[60]

Central Greece

The first regions to revolt in Central Greece were Phocis (24 March), and Salona (27 March). In Boeotia, Livadeia was captured by Athanasios Diakos on 31 March, followed by Thebes two days later. In mid-April revolutionary forces entered Athens, and forced the Turkish garrison into the Acropolis. Missolonghi revolted on 25 May, and the revolution soon spread to other cities of western Central Greece.[61]

These initial Greek successes were soon put in peril after two subsequent defeats at the battles of Alamana and Eleftherohori against the army of Omer Vrioni. Another significant loss for the Greeks was the death of Diakos, a promising military leader, who was captured in Alamana and executed by the Turks, when he refused to declare allegiance to the Sultan. The Greeks managed to halt the Turkish advance at the Battle of Gravia under the leadership of Odysseas Androutsos, who, with a handful of men, inflicted heavy casualties upon the Turkish army. After his defeat and the successful retreat of Androutsos' force, Omer Vrioni postponed his advance towards Peloponnese awaiting reinforcements; instead, he invaded Livadeia, which he captured on 10 June, and Athens, where he lifted the siege of Acropolis. After a Greek force of 2,000 men managed to destroy at Vassilika a Turkish relief army on its way to Turkish forces in Attica, Vrioni abandoned Attica in September and retreated to Ioannina. By the end of 1821, the revolutionaries had managed, after their victories at Vassilika and Gravia, to temporarily secure their positions in Central Greece.[62]

First administrative and political institutions

After the fall of Kalamata, the Messenian Senate, the first of the Greeks' local governing councils, held its inaugural session. At almost the same time, the Achean Directorate was summoned in Patras, but its members were soon forced to flee to Kalavryta. With the initiative of the Messenian Senate, a Peloponnesian assembly convened, and elected a Senate on 26 May. Most of the members of the Peloponnesian Senate were local notables (lay and ecclesiastical) or persons controlled by them. When Demetrios Ypsilantis arrived in Peloponnese as official representative of Filiki Eteria, he tried to assume control of the Revolution's affairs, and he thus proposed a new system of electing the members of the Senate, which was supported by the military leaders, but opposed by the notables.vi[›] Assemblies convened also in Central Greece (November 1821) under the leadership of two Phanariots: Alexandros Mavrokordatos in the western part, and Theodoros Negris in the eastern part. These assemblies adopted two local statutes, the Charter of Western Continental Greece and the Legal Order of Eastern Continental Greece, drafted mainly by Mavrokordatos and Negris respectively. The statutes provided for the creation of two local administrative organs in Central Greece, an Areopagus in the east, and a Senate in the west.[63] The three local statutes were recognized by the First National Assembly, but the respective administrative institutions were turned into administrative branches of the central government. They were later dissolved by the Second National Assembly.[64]

1822–24

Revolutionary activity was fragmented, because of the lack of a strong central leadership and guidance. However, the Greek side withstood the Turkish attacks, because, during the same period, the Ottoman military campaigns were periodic, and the Ottoman presence in the rebel areas uncoordinated due to logistical problems. The Greek military leaders preferred battlefields where they could annihilate the numerical superiority of the opponent, and, at the same time, the lack of artillery hampered Ottoman military efforts.[65]

The successive military campaigns of the Ottomans in Western and Eastern Greece were repulsed : in 1822 Mahmud Dramali Pasha crossed Roumeli and invaded Morea, but suffered a serious defeat in Dervenakia.[66] The 1823 campaign in Western Greece was led by Mustafa Reshit Pasha and Omer Vrioni ; during the summer the Souliot Markos Botsaris was shot dead at the Battle of Karpenisi in his attempt to stop the advance of the Ottomans;[67] the announcement of his death in Europe generated a wave of sympathy for the Greek cause. The campaign ended after the Second Siege of Missolonghi in December 1823.

Revolutionary activity in Crete, Macedonia and Cyprus

Crete

Cretan participation in the revolution was extensive, but it failed to achieve liberation from Turkish rule due to Egyptian intervention.[68] Crete had a long history of resisting Turkish rule, exemplified by the folk hero Daskalogiannis who was killed while fighting the Turks.[68] In 1821, an uprising by Christians was met with a fierce response from the Ottoman authorities and the execution of several bishops, regarded as ringleaders.[69]

Despite the Turkish reaction, the rebellion persisted, and thus Sultan Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839) was forced to seek the aid of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, trying to lure him with the pashalik of Crete.[68] On 28 May 1822, an Egyptian fleet of 30 warships and 84 transports, led by Hasan Pasha, Mehmet Ali's son-in-law, arrived at Souda Bay with the task of ending the rebellion and he did not waste any time in the burning of villages throughout Crete.[68]

After Hasan's accidental death in February 1823, another son-in-law of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, Hussein Bey[70] led a well-organised and well-armed joint Turkish-Egyptian force of 12,000 soldiers with the support of artillery and cavalry. He located his encampment at Ayia Varvara in Heraklion. On 22 June 1823, Emmanouil Tombazis, appointed Commissioner of Crete by the Greek revolutionary government, held the Convention of Arcoudaina in an attempt to reconcile the factions of local captains and unite them against the common threat.[71]

He then gathered 3,000 men in Gergeri to face Hussein. However, the Cretans were defeated by the much larger, and better organised force, and lost 300 men at the battle of Amourgelles on 20 August 1823.[72] By the spring of 1824, Hussein had managed to limit the Cretan resistance to just a few mountain enclaves.[73]

Towards the summer of 1825, a body of three to four hundred Cretans, who had fought with other Greeks in the Peloponnese, arrived in Crete, and revitalized the Cretan insurgency (the so-called "Gramvousa period"). On 9 August 1825, led by Dimitrios Kallergis and Emmanouil Antoniadis, this group of Cretans captured the fort at Gramvousa and other insurgents captured the fort at Kissamos, and attempted to spread the insurgency further afield.[74]

Although the Ottomans did not manage to retake the forts, they were successful in blocking the spread of the insurgency to western provinces. The insurgents were besieged in Gramvousa for more than two years and they had to resort to piracy to survive. Gramvousa became a hive of piratical activity that greatly affected Turkish–Egyptian and European shipping in the region. During that period the population of Gramvousa became organised and built a school and a church dedicated to the Panagia i Kleftrina ("Our Lady the piratess"), i.e., St. Mary as the patron of the klephts.[75]

In January 1828, the Epirote Hatzimichalis Dalianis together with 700 landed in Crete and in following March he took possession of Francocastello castle, Sfakia region. Soon the local Ottoman ruler, Mustafa Naili Pasha, attacked Frangokastello with an army of 8,000 men. The castle's defence was doomed after a seven-day siege and Dalianis perished along with 385 men.[76] During 1828, Kapodistrias sent Mavrocordatos with British and French fleets to Crete to deal with the klephts and the pirates. This expedition resulted in the destruction of all pirate ships at Gramvousa and the fort came under British command.[75]

Macedonia

The economic ascent of Thessaloniki and of the other urban centres of Macedonia coincided with the cultural and political renaissance of the Greeks. The ideals and patriotic songs of Rigas Feraios and others had made a profound impression upon the Thessalonians. Α few years later, the revolutionary fervour of the southern Greeks was to spread to these parts, and the seeds of Filiki Eteria were speedily to take root. The leader and coordinator of the revolution in Macedonia was Emmanouel Pappas from the village of Dobista, Serres, who was initiated into the Filiki Eteria in 1819. Papas had considerable influence over the local Ottoman authorities, especially the local governor, Ismail Bey, and offered much of his personal wealth for the cause.[77]

Following the instructions of Alexander Ypsilantis, that is to prepare the ground and to rouse the inhabitants of Macedonia to rebellion, Papas loaded arms and munitions from Constantinople on a ship on 23 March and proceeded to Mount Athos, considering that this would be the most suitable spring-board for starting the insurrection. As Vacalopoulos notes, however, "adequate preparations for rebellion had not been made, nor were revolutionary ideals to be reconciled with the ideological world of the monks within the Athonite regime".[78] On 8 May, the Turks, infuriated by the landing of sailors from Psara at Tsayezi, by the capture of Turkish merchants and the seizure of their goods, rampaged through the streets of Serres, searched the houses of the notables for arms, imprisoned the Metropolitan and 150 merchants, and seized their goods as a reprisal for the plundering by the Psarians.[79]

In Thessaloniki, governor Yusuf Bey (the son of Ismail Bey) imprisoned in his headquarters more than 400 hostages, of whom more than 100 were monks from the monastic estates. He also wished to seize the powerful notables of Polygyros, who got wind of his intentions and fled. On 17 May, the Greeks of Polygyros took up arms, killed the local governor and 14 of his men, and wounded three others; they also repulsed two Turkish detachments. On 18 May, when Yusuf learned of the incidents at Polygyros and the spreading of the insurrection to the villages of Chalkidiki, he ordered half of his hostages to be slaughtered before his eyes. The Mulla of Thessalonica, Hayrıülah, gives the following description of Yusuf's retaliations:

Every day and every night you hear nothing in the streets of Thessaloniki but shouting and moaning. It seems that Yusuf Bey, the Yeniceri Agasi, the Subaşı, the hocas and the ulemas have all gone raving mad.[80]

It would take until the end of the century for the city's Greek community to recover.[81] The revolt, however, gained momentum in Mount Athos and Kassandra, and the island of Thasos joined it.[82] Meanwhile, the revolt in Chalkidiki was progressing slowly and unsystematically. In June 1821 the insurgents tried to cut communications between Thrace and the south, attempting to prevent the serasker Hadji Mehmet Bayram Pasha from transferring forces from Asia Minor to southern Greece. Even though the rebels delayed him, they were ultimately defeated at the pass of Rentina.[83]

The insurrection in Chalkidiki was, from then on, confined to the peninsulas of Mount Athos and Kassandra. On 30 October 1821, an offensive led by the new Pasha of Thessaloniki, Mehmet Emin Abulubud, resulted in a decisive Ottoman victory at Kassandra. The survivors, among them Papas, were rescued by the Psarian fleet, which took them mainly to Skiathos, Skopelos and Skyros. However, Papas died en route to join the revolution at Hydra. Sithonia, Mount Athos and Thasos subsequently surrendered on terms.[84]

Nevertheless, the revolt spread from Central to Western Macedonia, from Olympus to Pieria and Vermion. In the autumn of 1821, Nikolaos Kasomoulis was sent to southern Greece as the "representative of South-East Macedonia", and met Demetrius Ypsilantis. He then wrote to Papas from Hydra, asking him to visit Olympus to meet the captains there and to "fire them with the required patriotic enthusiasm".[85] At the beginning of 1822, Anastasios Karatasos and Aggelis Gatsos arranged a meeting with other armatoloi; they decided that the insurrection should be based on three towns: Naoussa, Kastania, and Siatista.[86]

In March 1822, Mehmed Emin secured decisive victories at Kolindros and Kastania.[87] Further north, in the vicinity of Naousa, Zafeirakis Theodosiou, Karatasos and Gatsos organized the city's defense, and the first clashes resulted in a victory for the Greeks. Mehmed Emin then appeared before the town with 10,000 regular troops and 10,600 irregulars. Failing to get the insurgents to surrender, Mehmed Emin launched a number of attacks pushing them further back and finally captured Naousa in April, helped by the enemies of Zafeirakis, who had revealed an unguarded spot, the "Alonia".[88] Reprisals and executions ensued, and women are reported to have flung themselves over the Arapitsa waterfall to avoid dishonor and being sold in slavery. Those who broke through the siege of Naousa fell back in Kozani, Siatista and Aspropotamos River, or were carried by the Psarian fleet to the northern Aegean islands.[89]

Cyprus

On 9 June 1821 3 ships sailed from Cyprus with General Konstantinos Kanaris. They landed at Asprovrisi, of Lapithou. Kanaris brought with him papers from the Filiki Etaireia, and the ships were welcomed with rapturous applause and patriotic cries from the local Greeks of the area, who helped Kanaris and the soldiers from Cyprus as much as they could.

Kanaris brought with him the Cypriots who created the "Column of Cypriots" («Φάλαγγα των Κυπρίων»), led by General Chatzipetros, which fought with extraordinary heroism in Greece. In total, over 1000 Cypriots fought in the War of Independence, many of whom died. At Missolonghi many were killed, and at the Battle of Athens in 1827, around 130 were killed. General Chatzipetros, showing military decorations declared "These were given to me by the heroism and braveness of the Column of Cypriots". In the National Library, there is a list of 580 names of Cypriots who fought in the War between 1821 and 1829.

The Cypriot battalion brought with them their own distinctive war banner, consisting of a white flag with a large blue cross, and the words GREEK FLAG OF THE MOTHERLAND CYPRUS emblazoned in the top left corner. The flag was hoisted on a wooden mast, carved and pointed at the end to act as a lance in battle. The legendary battle flag is currently stored at the National Historical Museum of Athens.

Throughout the War of Independence, supplies were brought from Cyprus by the Filiki Etairia to aid the Greek struggle. The Greeks of Cyprus underwent great risk to provide these supplies, and secretly load them onto boats arriving at intervals from Greece, as the Ottoman Rulers in Cyprus at the time were very wary of Cypriot insurgency and sentenced to death any Greek Cypriots found aiding the Greek cause. Incidences of these secret loading trips from Cyprus were recorded by the French consul to Cyprus, Mechain.[90]

Back in Cyprus during the war, the local population suffered greatly at the hands of the Ottoman rulers of the islands, who were quick to act with great severity at acts of patriotism and sympathy of the Greeks of Cyprus to the Revolution, fearing a similar uprising in Cyprus. The leader of the Greeks of the island at the time, Archbishop Kyprianos was initiated into the Filiki Etairia in 1818 and had promised to aid the cause of the Greek Elladites with food and money.

In early July 1821, the Cypriot Archimandrite Theofylaktos Thiseas arrived in Larnaca as a messenger of the Filiki Etairia, bringing orders to Kyprianos, while proclamations were distributed in every corner of the island. However, the local pasha, Küçük Mehmet, intercepted these messages and reacted with fury, calling in reinforcements, confiscating weapons and arresting several prominent Cypriots. Archbishop Kyprianos was urged (by his friends) to leave the island as the situation worsened but refused to do so.

|

"Hellenism was born when the world was born,

|

| Archbishop Kyprianos' response to Kucuk Mehmet's threat to wipe out the Greeks of Cyprus[91] |

On 9 July 1821 Küçük Mehmet had the gates to the walled city of Nicosia closed and executed, by beheading or hanging, 470 important Cypriots amongst them Chrysanthos (bishop of Paphos), Meletios (bishop of Kition) and Lavrentios of (bishop of Kyrenia). The next day, all abbots and monks of monasteries of Cyprus were executed. In addition, the Ottomans arrested all the Greek leaders of the villages and imprisoned them before executing them, as they were suspected of inspiring patriotism in their local population.

In total, it is estimated that over 2,000 Greeks of Cyprus were slaughtered as an act of revenge for participating in the revolution. This was a very significant proportion of the total population of the island at the time. Küçük Mehmet had declared "I have in my mind to slaughter the Greeks in Cyprus, to hang them, to not leave a soul..." before undertaking these massacres. From the 9th to the 14 July, the Ottomans killed all prisoners on the list of the pasha, and in the next 30 days, looting and massacres spread throughout Cyprus as 4,000 Turkish soldiers from Syria arrived on the island.

Archbishop Kyprianos was defiant in his death. He was aware of his fate and impending death, yet stood by the Greek cause. He is revered throughout Cyprus as a noble patriot and defender of the Orthodox faith and Hellenic cause. An English explorer by the name of Carne spoke to the Archbishop before the events of 9 July, who was quoted as saying: "My death is not far away. I know they [the Ottoman] are waiting for an opportunity to kill me". Kyprianos chose to stay, despite these fears, and provide protection and counsel for the people of Cyprus as their leader. To this day, his response (in the form of a poem) to Küçük Mehmet's declaration (seen in the previous paragraph) to kill the Greeks of Cyprus in mass purges maintains legendary status in Cyprus and Greece.

He was publicly hanged from a tree opposite the former palace of the Lusignan Kings of Cyprus on 9 July 1821. The events leading up to his execution were documented in an epic poem written in the Cypriot dialect by Vassilis Michaelides.

War at sea

From the early stages of the revolution, success at sea was vital for the Greeks. If they failed to counter the Ottoman Navy, it would be able to resupply the isolated Ottoman garrisons and land reinforcements from the Ottoman Empire's Asian provinces at will, crushing the rebellion. The Greek fleet was primarily outfitted by prosperous Aegean islanders, principally from three islands: Hydra, Spetses and Psara. Each island equipped, manned and maintained its own squadron, under its own admiral.[92]

Although they were manned by experienced crews, the Greek ships were not designed for warfare, equipped with only light guns and staffed by armed merchantmen.[92] Against them stood the Ottoman fleet, which enjoyed several advantages: its ships and supporting craft were built for war; it was supported by the resources of the vast Ottoman Empire; command was centralized and disciplined under the Kapudan Pasha. The total Ottoman fleet size consisted of 23 masted ships of the line, each with about 80 guns and 7 or 8 frigates with 50 guns, 5 corvettes with about 30 guns and around 40 brigs with 20 or fewer guns.[93]

In the face of this situation, the Greeks decided to use fire ships (Greek: πυρπολικά or μπουρλότα), which had proven themselves effective for the Psarians during the Orlov Revolt in 1770. The first test was made at Eresos on 27 May 1821, when an Ottoman frigate was successfully destroyed by a fire ship under Dimitrios Papanikolis. In the fire ships, the Greeks found an effective weapon against the Ottoman vessels. In subsequent years, the successes of the Greek fire ships would increase their reputation, with acts such as the destruction of the Ottoman flagship by Constantine Kanaris at Chios, after the massacre of the island's population in June 1822, acquiring international fame. Overall, 59 fire ship attacks were carried out, of which 39 were successful.

At the same time, conventional naval actions were also fought, at which naval commanders like Andreas Miaoulis, Nikolis Apostolis, Iakovos Tombazis and Antonios Kriezis distinguished themselves. The early successes of the Greek fleet in direct confrontations with the Ottomans at Patras and Spetses gave the crews confidence and contributed greatly to the survival and success of the uprising in the Peloponnese.

Later, however, as Greece became embroiled in a civil war, the Sultan called upon his strongest subject, Muhammad Ali of Egypt, for aid. Plagued by internal strife and financial difficulties in keeping the fleet in constant readiness, the Greeks failed to prevent the capture and destruction of Kasos and Psara in 1824, or the landing of the Egyptian army at Methoni. Despite victories at Samos and Gerontas, the Revolution was threatened with collapse until the intervention of the Great Powers in the Battle of Navarino in 1827.

Revolution in peril

Infighting

The First National Assembly was formed at Epidaurus in late December 1821, consisted almost exclusively of Peloponnesian notables. The Assembly drafted the first Greek Constitution and appointed the members of an executive and a legislative body that were to govern the liberated territories. Mavrokordatos saved the office of president of the executive for himself, while Ypsilantis, who had called for the Assembly, was elected president of the legislative body, a place of limited significance.[94]

Military leaders and representatives of Filiki Eteria were marginalized, but gradually Kolokotronis' political influence grew, and he soon managed to control, along with the captains he influenced, the Peloponnesian Senate. The central administration tried to marginalize Kolokotronis who also had under his control the fort of Nafplion. In November 1822, the central administration decided that the new National Assembly would take place in Nafplio, and asked Kolokotronis to return the fort to the government. Kolokotronis refused, and the Assembly was finally gathered in March 1823 in Astros. Central governance was strengthened at the expense of regional bodies, a new constitution was voted, and new members were elected for the executive and the legislative bodies.[95]

Trying to coax the military leaders, the central administration proposed to Kolokotronis that he participate in the executive body as vice-president. Kolokotronis accepted, but he caused a serious crisis, when he prevented Mavrokordatos, who had been elected president of the legislative body, from assuming his position. His attitude towards Mavrokordatos caused outrage amongst the members of the legislative body.[96]

The crisis culminated, when the legislature, which was controlled by the Roumeliotes and the Hydriots, overturned the executive, and fired its president, Petros Mavromichalis. Kolokotronis and most of the Peloponnesian notables and captains supported Mavromichalis, who remained president of his executive in Tripolitsa. However, a second executive, supported by the islanders, the Roumeliotes, and some Achaean notables—Andreas Zaimis and Andreas Londos were the most prominent—was formed at Kranidi with Kountouriotis as president.[97]

In March 1824, the forces of the new executive besieged Nafplion and Tripolitsa. After one month of fighting and negotiations, an agreement was reached between Kolokotronis, from one side, and Londos and Zaimis, from the other side. On 22 May the first phase of the civil war officially ended, but most of the members of the new executive were displeased by the moderate terms of the agreement that Londos and Zaimis brokered.[97]

During this period, the two first instalments of the English loan had arrived, and the position of the government was strengthened; but the infighting was not yet over. Zaimis and the other Peloponnesians who supported Kountouriotis came into conflict with the executive body, and allied with Kolokotronis who roused the residents of Tripolitsa against the local tax collectors of the government. Papaflessas and Makriyannis failed to suppress the rebellion, but Kolokotronis remained inactive for some period, overwhelmed by the death of his son, Panos.[98]

The government regrouped its armies, which now consisted mainly of Roumeliotes and Souliots, and were led by Ioannis Kolettis who wanted a complete victory. Under Kolettis' orders, two bodies of Roumeliotes and Souliots invaded the Peloponnese: the first under Gouras occupied Corinth and raided the province; the second under Karaiskakis, Kitsos Tzavelas and others, attacked in Achaea Londos and Zaimis. In January 1825, a Roumeliote force, led by Kolettis himself arrested Kolokotronis, Deligiannis' family and others. In May 1825, under the pressure of the Egyptian intervention, those imprisoned were released and granted amnesty.[98]

Egypt intervenes to assist the Ottomans

Egyptian intervention was initially limited to Crete and Cyprus. However, the success of Muhammad Ali's troops in both places settled the Turks on the horns of a very difficult dilemma, since they were afraid of their wāli's expansionist ambitions. Muhammad Ali finally agreed to send his son Ibrahim Pasha to Greece in exchange not only for Crete and Cyprus, but for the Peloponnese and Syria as well.[99]

Ibrahim Pasha landed at Methoni on 24 February 1825 and a month later he was joined by his army of 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry.[100] He proceeded to defeat the Greek garrison on the small island of Sphacteria off the coast of Messenia.[101] With the Greeks in disarray, Ibrahim ravaged the Western Peloponnese and killed Papaflessas at the Battle of Maniaki.[102]

The Greek government, in an attempt to stop the Egyptians, released Kolokotronis from captivity, but he too was unsuccessful. By the end of June, Ibrahim had captured the city of Argos and was within striking distance of Nafplion. The city was saved by Commodore Gawen Hamilton of the Royal Navy who placed his ships in a position which looked like he would assist in the defence of the city.[102]

At the same time, the Turkish armies in Central Greece were besieging the city of Missolonghi for the third time. The siege had begun on 15 April 1825, the day on which Navarino had fallen to Ibrahim.[103] In early autumn, the Greek navy under the command of Miaoulis forced the Turkish fleet in the Gulf of Corinth to retreat, after attacking it with fire ships. The Turks were joined by Ibrahim in mid-winter, but his army had no more luck in penetrating Missolonghi's defences.[104]

In the spring of 1826, Ibrahim managed to capture the marshes around the city, although not without heavy losses. He thus cut the Greeks off from the sea and blocked off their supply route.[105] Despite the Egyptians and the Turks offering them terms to stop the attacks, the Greek refused and continued to fight.[106]

On 22 April the Greeks decided to sail from the city during the night with 3,000 men to cut a path through the Egyptian lines and allow 6,000 women, children and non-combatants to follow.[106] However, a Bulgarian deserter informed Ibrahim of the Greek's intention and he had his entire army deployed; only 1,800 Greeks managed to cut their way through the Egyptian lines. Between 3,000 and 4,000 women and children were enslaved and many of the people who remained behind decided to blow themselves up with gunpowder rather than be enslaved.[107]

Ibrahim sent an envoy to the Maniots demanding that they surrender or else he would ravage their land as he had done to the rest of the Peloponnese. Instead of surrendering, the Maniots simply replied:

| “ | From the few Greeks of Mani and the rest of Greeks who live there to Ibrahim Pasha. We received your letter in which you try to frighten us saying that if we don't surrender, you'll kill the Maniots and plunder Mani. That's why we are waiting for you and your army. We, the inhabitants of Mani, sign and wait for you.[108] |

” |

Ibrahim tried to enter Mani from the north-east near Almiro on 21 June 1826, but he was forced to stop at the fortifications at Vergas in northern Mani. His army of 7,000 men was held off by an army of 2,000 Maniots and 500 refugees from other parts of Greece until Kolokotronis attacked the Egyptians from the rear and forced them to retreat. The Maniots pursued the Egyptians all the way to Kalamata before returning to Vergas. Simultaneously, Ibrahim sent his fleet further down the Maniot coast in order to outflank the Greek defenders and attack them from the rear. However, when his force landed at Pyrgos Dirou, they were confronted by a group of Maniot women and repelled. Ibrahim again attempted to enter Mani from central Laconia, but again the Maniots defeated the Turkish and Egyptian forces at Polytsaravo. The Maniot victory dealt the death blow to Ibrahim's hope of occupying Mani.[109]

Foreign intervention against the Ottomans

Initial hostility

When the news of the Greek Revolution was first received, the reaction of the European powers was uniformly hostile. They recognized the degeneration of the Ottoman Empire but they did not know how to handle this situation (a problem known as the "Eastern Question"). Afraid of the complications the partition of the empire might raise, the British foreign minister Viscount Castlereagh, Austrian foreign minister Prince Metternich, and the Tsar of Russia Alexander I shared the same view concerning the necessity of preserving the status quo and the peace of Europe. They also pleaded that they maintain the Concert of Europe.

Metternich also tried to undermine the Russian foreign minister, Ioannis Kapodistrias, who was of Greek origin. Kapodistrias demanded that Alexander declare war on the Ottomans in order to liberate Greece and increase the greatness of Russia. Metternich persuaded Alexander that Kapodistrias was in league with the Italian Carbonari (an Italian revolutionary group) leading Alexander to disavow him. As a result of the Russian reaction to Alexander Ypsilantis, Kapodistrias resigned as foreign minister and moved to Switzerland.[110]

Nevertheless, Alexander's position was ambivalent, since he regarded himself as the protector of the Orthodox Church, and his subjects were deeply moved by the hanging of the Patriarch. These factors explain why, after denouncing the Greek Revolution, Alexander dispatched an ultimatum to Constantinople on 27 July 1821. However, the danger of war passed temporarily, after Metternich and Castlereagh persuaded the Sultan to make some concessions to the Tsar.[111] On 14 December 1822, the Holy Alliance denounced the Greek Revolution, considering it audacious.

Change of stance

.jpg)

Right:Tsar Nicholas I co-signed the Treaty of London, and then launched the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829, which finally secured Greek independence.

In August 1822, George Canning was appointed by the British government as Foreign Secretary succeeding Castlereagh. Canning was influenced by the mounting popular agitation against the Ottomans and believed that a settlement could no longer be postponed. He also feared that Russia might undertake unilateral action against the Ottoman Empire.[112]

In March 1823, Canning declared that "when a whole nation revolts against its conqueror, the nation cannot be considered as piratical but as a nation in a state of war". In February 1823 he notified the Ottoman Empire that Britain would maintain friendly relations with the Turks only under the condition that the latter respected the Christian subjects of the Empire. The Commissioner of the Ionian Islands, which belonged to Britain, was ordered to consider the Greeks in a state of war and give them the right to cut off certain areas from which the Turks could get provisions.[43]

These measures led to the increase of British influence. This influence was reinforced by the issuing of two loans that the Greeks managed to conclude with British fund-holders in 1824 and 1825. These loans, which, in effect, made the City of London the financier of the revolution,[43] inspired the creation of the "British" political party in Greece, whose opinion was that the revolution could only end in success with the help of Britain. At the same time, parties affiliated to Russia and France made their appearance. These parties would later strive for power during king Otto's reign.[113]

When Tsar Nicholas I succeeded Alexander in December 1825, Canning decided to act immediately: he sent the Duke of Wellington to Russia, and the outcome was the St. Petersburg Protocol of 4 April 1826. According to the protocol, the two powers agreed to mediate between the Ottomans and the Greeks on the basis of complete autonomy of Greece under Turkish sovereignty. Before he met with Wellington, the Tsar had already sent an ultimatum to the Porte, demanding that the principalities be evacuated immediately and that plenipotentiaries be sent to Russia to settle outstanding issues. The Sultan agreed to send the plenipotentiaries, and on 7 October 1826 signed the Akkerman Convention, in which Russian demands concerning Serbia and the principalities were accepted.[114]

The Greeks formally applied for the mediation provided in the Petersburg Protocol, while the Turks and the Egyptians showed no willingness to stop fighting. Canning therefore prepared for action by negotiating the Treaty of London (6 July 1827) with France and Russia. This provided that the Allies should again offer negotiations, and if the Sultan rejected it they would exert all the means which circumstances would allow to force the cessation of hostilities. Meanwhile, news reached Greece in late July 1827 that Mehmet Ali's new fleet was completed in Alexandria and sailing towards Navarino to join the rest of the Egyptian-Turkish fleet. The aim of this fleet was to attack Hydra and knock the island's fleet out of the war. On 29 August, the Porte formally rejected the Treaty of London's stipulations, and, subsequently, the commanders-in-chief of the British and French Mediterranean fleets, Admiral Edward Codrington and Admiral Henri de Rigny sailed into the Gulf of Argos and requested to meet with Greek representatives on board the HMS Asia.[115]

Battle of Navarino (1827)

After the Greek delegation, led by Mavrocordatos, accepted the terms of the treaty, the Allies prepared to insist upon the armistice, and their fleets were instructed to intercept supplies destined for Ibrahim's forces. When Mehmet Ali's fleet, which had been warned by the British and French to stay away from Greece, left Alexandria and joined other Ottoman/Egyptian units at Navarino on 8 September, Codrington arrived with his squadron off Navarino on 12 September. On 13 October, Codrington was joined, off Navarino, by his allied support, a French squadron under De Rigny and a Russian squadron under L. Heyden.[116]

Upon their arrival at Navarino, Codgrinton and de Rigny tried to negotiate with Ibrahim but Ibrahim insisted that by the Sultan's order he must destroy Hydra. Codrington responded by saying that if Ibrahim's fleets attempted to go anywhere but home, he would have to destroy them. Ibrahim agreed to write to the Sultan to see if he would change his orders but he also complained about the Greeks being able to continue their attacks. Codrington promised that he would stop the Greeks and Philhellenes from attacking the Turks and Egyptians. After doing this, he disbanded most of his fleet which returned to Malta while the French went to the Aegean.[116]

However, when Frank Hastings, a Philhellene, destroyed a Turkish naval squadron, Ibrahim sent out a detachment of his fleet out of Navarino in order to defeat Hastings. Codrington had not heard of Hastings's actions and thought that Ibrahim was breaking his agreement. Codrington intercepted the force and made them retreat and did so again on the following day when Ibrahim lead the fleet in person. Codrington assembled his fleet once more, with the British returning from Malta and the French from the Aegean. They were also joined by the Russian contingent led by Count Login Geiden. Ibrahim now began a campaign to annihilate the Greeks of the Peloponnese as he thought the Allies had reneged on their agreement.[117]

On 20 October 1827, as the weather got worse, the British, Russian and French fleets entered the Bay of Navarino in peaceful formation to shelter themselves and to make sure that Egyptian-Turkish fleet did not slip off and attack Hydra. When a British frigate sent a boat to request the Egyptians to move their fire ships, the officer on board was shot by the Egyptians. The frigate responded with musket fire in retaliation and an Egyptian ship fired a cannon shot at the French flagship, the Sirene, which returned fire.[118]

A full engagement was begun which ended in a complete victory for the Allies and in the annihilation of the Egyptian-Turkish fleet. Of the 89 Egyptian-Turkish ships that took part in the battle, only 14 made it back to Alexandria and their dead amounted to over 8,000. The Allies didn't lose a ship and suffered only 181 deaths. The Porte demanded compensation from the Allies for the ships but his demand was refused on the grounds that the Turks had acted as the aggressors. The three countries' ambassadors also left Constantinople.[119]

In Britain, the battle was criticized as being an 'untoward event' towards Turkey who was called an 'ancient ally'. Codrington was recalled and blamed for having allowed the retreating Egyptian-Turkish ships to carry 2,000 Greek slaves. In France, the news of the battle was greeted with great enthusiasm and the government had an unexpected surge in popularity. Russia formally took the opportunity to declare war on the Turks.[119]

In October 1828, the Greeks regrouped and formed a new government under Kapodistrias. They then advanced to seize as much territory as possible, including Athens and Thebes, before the Western powers imposed a ceasefire. As far as the Peloponnese was concerned, Britain and Russia accepted the offer of France to send an army to expel Ibrahim's forces. Nicolas Joseph Maison, who was given command of the French expeditionary Corps, landed on 30 August 1828 at Petalidi, and helped the Greeks evacuate the Peloponnese from all the hostile troops by 30 October . Maison thus implemented the convention Codrington had negotiated and signed in Alexandria with Muhammad Ali, and which provided for the withdrawal of all Egyptian troops from the Peloponnese.[120]

The final major engagement of the war was the Battle of Petra, which occurred north of Attica. Greek forces under Demetrius Ypsilantis, for the first time trained to fight as a regular European army rather than as guerrilla bands, advanced against Aslan Bey's forces and defeated them. The Turks surrendered all lands from Livadeia to the Spercheios River in exchange for safe passage out of Central Greece. As George Finlay stresses:[121]

Thus Prince Demetrius Hypsilantes had the honor of terminating the war which his brother had commenced on the banks of the Pruth.

From autonomy to independence

On 21 December 1828 the ambassadors of Britain, Russia, and France met in the island of Poros, and prepared a protocol, which provided for the creation of an autonomous state ruled by a monarch, whose authority should be confirmed by a firman of the Sultan. The proposed borderline ran from Arta to Volos, and, despite Kapodistrias' efforts, the new state would include only the islands of Cyclades, Sporades, Samos, and maybe Crete. Based on the Protocol of Poros, the London Conference agreed on the protocol of 22 March 1829, which accepted most of the ambassadors' proposals, but drew the borders farther south than the initial proposal, and did not include Samos and Crete in the new state.[122]

Under the pressure of Russia, the Porte finally agreed on the terms of the Treaty of London of 6 July 1827, and of the Protocol of 22 March 1829. Soon afterward, Britain and France conceived the idea of an independent Greek state, trying to limit the influence of Russia on the new state.[123] Russia disliked the idea, but could not reject it, and, consequently, the three powers finally agreed to create an independent Greek state under their joint protection, and concluded the protocols of 3 February 1830.[124]

By one of the protocols, the Greek throne was initially offered to Leopold, Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and the future King of Belgium. Discouraged by the gloomy picture painted by Kapodistrias and unsatisfied with the Aspropotamos-Zitouni borderline, which replaced the more favorable line running from Arta to Volos considered by the Great Powers earlier, he refused. Negotiations temporarily stalled after Kapodistrias was assassinated in 1831 in Nafplion by the Mavromichalis' clan after having demanded that they unconditionally submit to his authority. When they refused, Kapodistrias put Petrobey in jail, sparking vows of vengeance from his clan.[125]

The withdrawal of Leopold as a candidate for the throne of Greece and the July Revolution in France further delayed the final settlement of the new kingdom's frontiers until a new government was formed in Britain. Lord Palmerston, who took over as British Foreign Secretary, agreed to the Arta–Volos borderline. However, the secret note on Crete, which the Bavarian plenipotentiary communicated to Britain, France and Russia, bore no fruit.

In May 1832, Palmerston convened the London Conference. The three Great Powers (Britain, France and Russia) offered the throne to the Bavarian prince, Otto of Wittelsbach, meanwhile the Fifth National Assembly at Nafplion had approved the choice of Otto and passed the Constitution of 1832 (which would come to be known as the "Hegemonic Constitution"). As co-guarantors of the monarchy, the Great Powers also agreed to guarantee a loan of 60 million francs to the new king, empowering their ambassadors in the Ottoman capital to secure the end of the war. Under the protocol signed on May 7, 1832 between Bavaria and the protecting powers, Greece was defined as a "monarchical and independent state" but was to pay an indemnity to the Porte. The protocol outlined the way in which the Regency was to be managed until Otto reached his majority, while also concluding the second Greek loan for a sum of £2.4 million.[126]

On 21 July 1832, British Ambassador to the Sublime Porte Sir Stratford Canning and the other representatives of the Great Powers signed the Treaty of Constantinople, which set the boundaries of the new Greek Kingdom at the Arta–Volos line.[127] The borders of the kingdom were reiterated in the London Protocol of August 30, 1832, also signed by the Great Powers, which ratified the terms of the Constantinople arrangement.[128]

Massacres

Almost as soon as the revolution began, there were large scale massacres of civilians by both Greek revolutionaries and Ottoman authorities.vii[›] Greek revolutionaries massacred Turks and Muslims, mainly inhabitants of the Peloponnese and Attica where Greek forces were dominant, identifying them with the Ottoman rule.[129] On the other hand, the Turks massacred Greeks identified with the revolution especially in Anatolia, Crete, Constantinople, Cyprus, Macedonia and the Aegean islands.[130]

Some of the more infamous atrocities include the Chios Massacre, the Destruction of Psara, the massacres following the Tripolitsa Massacre, and the Navarino Massacre. There is a debate among scholars over whether the massacres committed by the Greeks should be regarded as a response to prior events (such as the massacre of the Greeks of Tripoli, after the failed Orlov Revolt of 1770 and the destruction of the Sacred Band[131]) or as separate atrocities, which started simultaneously with the outbreak of the revolt.[132]

During the war, tens of thousands of Greek civilians were killed, left to die or taken into slavery.[133] Most of the Greeks in the Greek quarter of Constantinople were massacred.[134] A large number of Christian clergymen were also killed, including the Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory V.viii[›]

Sometimes marked as allies of the Turks in the Peloponnese, Jewish settlements were also massacred by Greek revolutionaries; the tragedy may have been more a side-effect of the butchering of the Turks of Tripolis, the last Ottoman stronghold in the South where the Jews had taken refuge from the fighting, than a specific action against Jews as such. Many Jews around Greece and throughout Europe were supporters of the Greek revolt, using their resources to loan substantial amounts to the newly formed Greek government. In turn, the success of the Greek Revolution was to stimulate the incipient stirrings of Jewish nationalism, later called Zionism. Following its establishment, the new state attracted a number of Jewish immigrants from Central Europe and the Ottoman Empire.[135]

Aftermath

The consequences of the Greek revolution were somewhat ambiguous in the immediate aftermath. An independent Greek state had been established, but with Britain, Russia and France claiming a major role in Greek politics, an imported Bavarian dynast as ruler, and a mercenary army.[136] The country had been ravaged by ten years of fighting, was full of displaced refugees and empty Turkish estates, necessitating a series of land reforms over several decades.[36]

The population of the new state numbered 800,000, representing less than one-third of the 2.5 million Greek inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire. During a great part of the next century, the Greek state sought the liberation of the "unredeemed" Greeks of the Ottoman Empire, in accordance with the Megali Idea, i.e., the goal of uniting all Greeks in one country.[36]

As a people, the Greeks no longer provided the princes for the Danubian Principalities and were regarded within the Ottoman Empire, especially by the Muslim population, as traitors. Phanariotes, who had until then held high office within the Ottoman Empire, were thenceforth regarded as suspect and lost their special, privileged status. In Constantinople and the rest of the Ottoman Empire where Greek banking and merchant presence had been dominant, Armenians mostly replaced Greeks in banking and Jewish merchants gained importance.[137]

| "Today the fatherland is reborn, that for so long was lost and extinguished. Today are raised from the dead the fighters, political, religious, as well as military, for our King has come, that we begat with the power of God. Praised be your most virtuous name, omnipotent and most merciful Lord." |

| Makriyannis' Memoirs on the arrival of King Otto. |

In the long-term historical perspective, this marked a seminal event in the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, despite the small size and the impoverishment of the new Greek state. For the first time, a Christian subject people had achieved independence from the Ottoman rule and established a fully independent state, recognized by Europe. Whereas previously only large nations (such as the British or the French) were judged worthy of national self-determination by the Great Powers of Europe, the Greek Revolt legitimized the concept of small ethnically based nation-states and emboldened nationalist movements among other subject peoples of the Ottoman Empire. The Serbs, Bulgarians, Romanians and Armenians all subsequently fought for and won their independence.

Shortly after the war finished, the people of the Russian-dependent Poland, encouraged by the Greek victory, started the November Uprising, hoping to regain their independence. The uprising, however, failed and Polish independence had to wait until 1918. The newly established Greek state would become a springboard for further expansion and, over the course of a century, parts of Macedonia, Crete, Epirus, many Aegean Islands and other Greek-speaking territories would unite with the new Greek state.

Gallery

Personalities

Events

-

"The Sacred Band at the Battle of Dragashani" by Peter von Hess.

-

"Execution of Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople" by Nikiphoros Lytras.

-

"Kephalas plants the flag of liberty upon the walls of Tripolizza" (Siege of Tripolitsa)" by Peter von Hess.

-

Antonis Oikonomou starts the revolution in Hydra by Peter von Hess.

-

Markos Botsaris dying in Karpenisi by Peter von Hess.

-

"The destruction of the Ottoman flagship at Chios by Constantine Kanaris" by Nikiphoros Lytras.

-

"The camp of Georgios Karaiskakis at Kastella" by Theodoros Vryzakis.

-

"Greece on the ruins of Missolonghi" by Eugène Delacroix.

-

"After the destruction of Psara" by Nikolaos Gysis.

-

.jpg)

"Grateful Hellas" by Theodoros Vryzakis.

See also

Notes

^ i: Adanir refers to the "mountainous districts such as Mani in the Peloponnese or Souli and Himara in Epirus, which had never been completely subjugated".[138]

^ ii: Reʿâyâ. An Arabic word meaning "flock" or "herd animal".[15]

^ iii: Georgiadis–Arnakis argues that the Church of Constantinople conducted "a magnificent work of national conservation", and contributed to the national liberation of all the subject nationalities of the Balkan peninsula.[139]

^ iv: In the Morea, there did not exist any armatoloi; wealthy landowners and primates hired the kapoi serving as personal bodyguards and rural police.[140]

^ v: Clogg asserts that uncertainty surrounds the total number of those recruited into the Filiki Eteria. According to Clogg, recruiting was carried out in the Danubian principalities, southern Russia, the Ionian islands and the Peloponnese. Few were recruited in Rumeli, the Aegean islands or Asia Minor.[141]

^ vi: As Koliopoulos & Veremis argue, Ypsilantis proposed a smaller electorate, limited to the more "prestigious" men of the districts. On the other hand, the notables insisted on the principle of universal suffrage, because they were confident that they could secure the support of their people. They thus advocated "democratic" principles, while Ypsilantis and the military promoted "aristocratic" procedures. Koliopoulos & Veremis conclude that "Ypsilantis' assembly was essentially a royal chamber, while that of the local notables was closer to a parliament".[142]

^ vii: St. Clair characterizes the Greek War of Independence as "a series of opportunist massacres".[143]

^ viii: As they did in similar cases in the past, the Turks executed the Patriarch after they had had him deposed and replaced, not as patriarch but as a disloyal subject. Georgiades–Arnakis asserts that "though the Porte took care not to attack the church as an institution, Greek ecclesiastical leaders knew that they were practically helpless in times of trouble."[139]

Citations

- ↑ Note: Greece officially adopted the Gregorian calendar on 16 February 1923 (which became 1 March). All dates prior to that, unless specifically denoted, are Old Style.

- 1 2 The War Chronicles: From Flintlocks to Machine Guns: A Global Reference of ... , Joseph Cummins, 2009, p.60

- 1 2 3 The War Chronicles: From Flintlocks to Machine Guns: A Global Reference of ... , Joseph Cummins, 2009, p.50

- ↑ Caroline Finkel Osman's Dream p.17

- ↑ Woodhouse, A Story of Modern Greece, 'The Dark Age of Greece (1453–1800)', p. 113, Faber and Faber (1968)

- 1 2 Barker, Religious Nationalism in Modern Europe, p. 118

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, (2004)

- ↑ Bisaha, Creating East and West, 114–115

* Milton (& Diekhoff), Milton on himself, 267 - ↑ Bisaha, Nancy (2004). Creating East and West: Renaissance humanists and the Ottoman Turks. University of Pennsylvania Prees ISBN 0-8122-3806-0. p. 114.

- ↑ Kassis, Mani's History, p. 29.

- ↑ Kassis, Mani's History, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Svoronos, History of Modern Greece, p. 59

* Vacalopoulos, History of Macedonia, p.336 - ↑ Kassis, Mani's History, p. 35.

- ↑ Svoronos, History of Modern Greece, p. 59

- 1 2 Georgiadis–Arnakis, The Greek Church of Constantinople, p. 238

- ↑ Paparrigopoulos, History of the Hellenic Nation, Eb, p. 108

* Svoronos, The Greek Nation, p. 89

* Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey", p. 241 - ↑ Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, pp. 9, 40–41

- ↑ Koliopoulos, Brigands with a Cause, p. 27

- ↑ Vacalopoulos, The Greek Nation, 1453–1669, p. 211

- 1 2 Batalas, Irregular Armed Forces, p. 156

- ↑ Batalas, Irregular Armed Forces, p. 154

- ↑ Batalas, Irregular Armed Forces, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Koliopoulos, Brigands with a Cause, p. 29

- ↑ Makriyannis, Memoirs, IX

- ↑ Stoianovich, The Conquering Balkan Orthodox Merchant pp. 310–12

- ↑ Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey", p. 241

- 1 2 Clogg, A Concise History of Greece , pp. 25–26

- 1 2 Goldstein, Wars and Peace Treaties, p. 20

- 1 2 Boime, Social History of Modern Art, pp. 194–196

* Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey", p. 241 - ↑ Svoronos, History of Modern Greece, p. 62

- ↑ Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, p. 29.

- ↑ Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, p. 6

- ↑ Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, p. 31

* Dakin, The Greek struggle for independence, pp. 41–42 - 1 2 Jelavich, History of the Balkans, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, pp. 31–32

- 1 2 3 Sowards, Steven (14 June 1999). "Twenty-five Lectures on Modern Balkan History: The Greek Revolution and the Greek State". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ↑ Richard, Laura E. Letters and Journals of Samuel Gridley Howe, pages 21–26. Boston: Dana Estes & Company, 1909.

- ↑ Wynne William H., (1951), State insolvency and foreign bondholders, New Haven, Yale University Press, vol. 2, p. 284

- ↑ Boime, Social History of Modern Art, 191