Greeks in Albania

About a general view on history, geography, demographics and political issues concerning the region, see Northern Epirus.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

est. over 215,000 (Greeks of southern Albania/Northern Epirus) Greeks of southern Albania/Northern Epirus (including those of ancestral descent) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Albania, Greece, United States, Australia | |

| Albania and Greece | est. over 200.000[1][2] |

| United States of America | over 15,000 (est. 1965)[3] |

| Languages | |

|

Greek, Himariote Greek dialect (in the Himarë region) also Albanian and English depending on the residing place | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christianity | |

The Greeks of Albania are ethnic Greeks who live in or originate from areas within modern Albania. They are mostly concentrated in the south of the country, in the areas of the northern part of the historical region of Epirus, in parts of Vlorë County,[4] Gjirokastër, Korçë[5] and Berat County.[6] The area is also known as Northern Epirus. Consequently, the Greeks hailing specifically from South Albania/Northern Epirus are widely known as Northern Epirotes (Greek: Βορειοηπειρώτες Vorioipirotes, Albanian: Vorioepirot). The Greeks who live in the 'minority zones' of Albania are officially recognized by the Albanian government as the Greek National Minority of Albania (Greek: Ελληνική Μειονότητα στην Αλβανία, Elliniki Mionotita stin Alvania, Albanian: Minoriteti Grek në Shqipëri).[7][8]

In 1913, after the end of five centuries of Ottoman rule, the area was included under the sovereignty of the newly founded Albanian state. The following year, Greeks revolted and declared their independence, and with the following Protocol of Corfu the area was recognized as an autonomous region under nominal Albanian sovereignty. However, this was never implemented.

In modern times, the Greek population has suffered from the prohibition of the Greek language if spoken outside the recognized so-called 'minority zones' (which have remained after the communist era) and even limitations on the official use of its language within those zones.[9] According to Greek minority leaders, the existence of Greek communities outside the 'minority zones' is even outright denied.[10] Many formerly Greek place-names have been officially changed to Albanian ones.[11] Greeks from the 'minority zones' were also frequently forcibly moved to other parts of the country since they were seen as possible sources of dissent and ethnic tension. During communist rule many Greek members of Albanian political parties were forced to cut off their ties with the Orthodox Church.[9] In more recent times, the numbers of the minority have dwindled.

It is important to note that the total number of Greeks in Albania has been disputed for a very long time.[12] Both Albania and Greece hold different and often conflicting estimations, as they have done so for the last 20 years.[13] In addition, the Greek National Minority of Albania also holds a different view, with the most recent so called 'Greek census' in Albania by the group Omonoia putting the number at 287,000 (within Albania and some parts of Greece only). This census is not recognised by the Albanian government.[14] The total Greek population in Albania, both historically and presently is no more than 300,000 by modest estimates. In addition 189,000 reside in Greece who are Albanian nationals.[2] It is believed that the total number of Greeks from Albania is no more than 550,000 including ancestry within Albania and Greece. The numbers may be higher when considering intermarriages, assimilation and wider diaspora.[15]

Northern Epirus

The Greek minority in Albania is concentrated in the south of the country, along the border with Greece, an area referred to by Greek as "Northern Epirus". The largest concentration is in the districts of Sarandë, Gjirokastër (especially in the area of Dropull), Delvinë, and in Himara (part of the district of Vlorë). Smaller groups can be found in the districts of Kolonjë, Përmet and Korçë. In addition, Greeks communities are found in all the large cities of Albania, including the capital Tiranë, Fier, Durrës, Elbasan, and Shkodër.[16] In more recent times, the numbers of the minority have dwindled. According to an estimate in 2005 more than 80% have migrated to Greece.[17] However, in more recent years the majority of emigrants holding Albanian citizenship in general dropped and many of them eventually returned from Greece to Albania.[18] As a result in regions such as Himara, part of the ethnic Greek communities that initially moved to Greece have returned.[19]

Recognized Greek 'minority zone'

During the communist regime (1945–1991), Enver Hoxha, in order to establish control over the areas populated by the Greek minority, declared the so-called “minority zones” (Albanian: Zona e minoritarëve), consisting of 99 villages in the southern districts of Gjirokastër, Sarandë and Delvina.[20]

Tirana's official minority policy defines the Greek origin of Albanian citizens according to the language, religion, birth and ancestors originating from the areas of the so-called “minority zones”. The Albanian law on minorities acknowledges the rights of the Greek minority only to those people who live in the areas which are recognized as minority zones. The last census that included ethnicity, from 1989, included only the numbers of the Greek minority in the minority zones.[9] Ethnic Greeks living outside those areas were not counted as such. This has had a practical effect in the area of education: With the exception of the officially-recognized Greek minority zones, where teaching was held in both the Greek and Albanian languages, in all other areas of Albania lessons were taught only in the Albanian language.[21]

Albanian PM Edi Rama in 2013 stated the Greek minority is not isolated within the "minority zones" but "all over the nation"[22][23]

Other Greek communities in Albania

However, the official Albanian definition about minorities did not recognize as members of a minority ethnic Greeks who live in mixed villages and towns inhabited by both Greek and Albanian speaking populations, even in areas where ethnic Greeks form a majority (e.g. Himara).[9][24] Consequently, the Greek communities in Himarë, Korce, Vlorë and Berat did not have access to any minority rights.[25][26]

Contrary to the official Albanian definition, that generally provides a limited definition of the ethnic Greeks living in Albania, Greek migration policy defines the Greek origin on the basis of language, religion, birth and ancestors from the region called Northern Epirus. In that way, according to the Greek State Council, the Greek ethnic origin can be granted on the basis of cultural ancestry (sharing “common historical memories” and/or links with “historic homelands and culture”), Greek descent (Greek Albanians have to prove that the birthplace of their parents or grandparents is in Northern Epirus), language, and religion.[25]

Albanian sources often use the pejorative term 'filogrek' (pro-Greek) in relation to ethnic Greeks, usually in a context disputing their Greek ancestry.[27]

Aromanians

A substantial number of Vlachs (Aromanians) in the region have historically self-identified as Greeks. They are mostly concentrated in the southern part of the country in the districts of Sarandë, Vlorë, Fier, Gjirokastër, Përmet, Tepelenë, Devoll and Korçë.[28] Vickers suggests that a certain number of them have claimed to be Greek in exchange for benefits such as Greek pensions, Greek Passports and visas.[29]

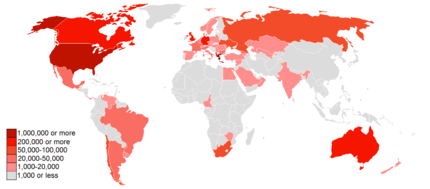

Diaspora

Greece

At the end of the second World War approximately 35,000 Northern Epirotes found refuge in Greece.

Since the collapse of the communist regime in Albania in 1990, an estimated 200,000 ethnic Greeks from Albania are believed to live and work (some of them on a seasonal basis) in Greece as immigrants.[30] They are considered 'omogeneis' (co-ethnics) by the Greek Ministry of the Interior and have received special residency permits available only to members of the Greek minority from Albania.[31]

North America

A number of Northern Epirotes have migrated since the late 19th century to the Americas, and are generally integrated in the local Greek-American communities. The Pan-Epirotic Union of America, an organization which consists of 26 branches in various cities, according to its estimates counted nearly 30,000 Northern Epirotes in North America in 1919.[32] Notably, in the same year around 1,700 members of the Greek Northern Epirote diaspora from Korce (Korytsa) and Kolonje (Kolonia) petitioned the on-going Paris Peace Conference for the unification of the region with Greece.[33]

According to post-war sources, Northern Epirotes in America numbered over 15,000 families in 1965.[3]

Australia

Northern Epirotes also emigrated in Australia, where they are active in raising political issues related to their motherland and the rights of the Greek populations still living there.[34] The largest number of such persons are in the state of Victoria.

Culture

Language

Northern Epirotes speak a southern Greek dialect.[35] In addition to Albanian loanwords, it retains some archaic forms and words that are no longer used in Standard Modern Greek, as well as in the Greek dialects of southern Epirus. Despite the relatively small distances between the various town and villages, there exists some dialectal variation,[36] most noticeably in accent.[25] Though Northern Epirote is a southern dialect, it is located far north of the reduced unstressed vowel system isogloss with the archaic disyllabic -ea. Thus, the provenance of the dialect ultimately remains obscure, and more research in this direction is needed.[35]

The local Greek dialects (especially the Chimariotic and the Argyrokastritic) are a more conservative and a purer Greek idiom (similarly to that spoken in the Mani peninsula in Greece, and the Griko language of Apulia in Italy), because they were spoken by populations living under virtual autonomy during Ottoman rule due to the rugged nature of the region. Thus, separated from other Greek dialects, the Northern Epirote Greek dialect underwent slower evolution, preserving a more archaic and faithful picture of the medieval Greek vernacular. The isolation of Albania during the years of communist rule, which separated the Greeks living in Albania from other Greek communities, also contributed to the slower evolution and differentiation of the local Greek dialects.

Religion

Christianity spread to the region during the 4th century. The following centuries saw the erection of characteristic examples of Byzantine architecture such as the churches in Kosine, Mborje and Apollonia. Later, between 1500–1800, impressive ecclesiastical art flourished across Northern Epirus. In Moscopole there were over 23 churches during the city's period of prosperity in the mid 18th century.[26] Post-Byzantine architectural style is prevalent in the region, e.g. in Vithkuq, Labove, Mesopotam, Dropull.[3]

Music

Epirote folk music has several unique features not found in the rest of the Greek world. Singers from the Pogon region (as well as in the Greek part of Upper Pogoni) perform a style of polyphony -typically shared with the Albanian and Vlach music of Epirus- that is characterized by a pentatonic structure.[37] Another type of polyphonic singing in the region seems to have features in common with the lament songs (Greek: Μοιρολόγια) sung in some parts of Greece.[38] The female lament singing of Northern Epirus is similar in nature and performance with that of the Mani peninsula in Greece.[39] In recent years there has been a growing interest in polyphonic music from this region, most notably by noted musician Kostas Lolis, born near what the Greeks call Sopiki in Albania but now resident in Ioanina in the Hellenic Republic.

Education

Ottoman era

During the first period of Ottoman occupation, illiteracy was a main characteristic of the wider Balkan region, but contrary to that situation, Epirus was not negatively affected. Along with the tolerance of the Turkish rulers and the desires of wealthy Epirote emigrants in the diaspora, many schools were established.

The spiritual and ethnic contribution of the monastery schools in Epirus such as Katsimani (near Butrint), Drianou (in Droviani), Kamenas (in Delvina) and St. Athanasios in Poliçani (13th-17th century) was significant. The first Greek-language school in Delvine was founded in 1537,[40] when the town was still under Venetian control, while in Gjirokastër a Greek school was founded in 1633.[3] The most important impetus for the creation of schools and the development of Greek education was given by the Orthodox missionary Cosmas of Aetolia together with the Aromanian Nektarios Terpos from Moscopole.[41][42] Cosmas the Aetolian founded the Acroceraunian School, harkening back to the region's name in classical antiquity, in the town of Himara in 1770.

In Moscopole, an educational institution known as the ""New Academy" (Greek: Νέα Ακαδημία) and an extensive library were established during the 18th century. A local Epirote monk founded in 1731 the first printing-press in the Balkans (second only to that of Constantinople). However, after the destruction of Moscopole (1769), the center of Greek education in the region moved to nearby Korçë.[3]

In the late 19th century, the wealthy banker Christakis Zografos founded the Zographeion College in his hometown of Qestorat, in the region of Lunxhëri.[27] Many of the educated men that supported Greek culture and education in the region, then the culture of the Orthodox Patriarchate, were Vlachs by origin. In 1905, Greek education was flourishing in the region, as the entire Orthodox population, including Orthodox Albanians, was educated in Greek schools.[43]

| “ | In Epirus, as throughout Turkey, a Greek village without a teacher, says a proverb, is as rare as a valley without the corresponding hills. In villages where I could count more than one hundred houses, the teachers showed me their libraries. Instruction is not compulsory but none would consent to deprive his child of an education. |

” |

| — — Dumont, Albert. La Turquie d'Europe. mid. 19th century[44] | ||

| Sandjak | District | No. of Greek schools |

Pupils |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monastir | Korce | 41 | 3,452 |

| Kolonje | 11 | 390 | |

| Leskovik | 34 | 1,189 | |

| Gjirokastër | Gjirokastër | 50 | 1,916 |

| Delvine | 24 | 1,063 | |

| Permet | 35 | 1,189 | |

| Tepelene | 18 | 589 | |

| Himare | 3 | 507 | |

| Pogon | 42 | 2,061 | |

| Berat | Berat | 15 | 623 |

| Skrapar | 1 | 18 | |

| Lushnjë | 28 | 597 | |

| Vlore | 10 | 435 | |

| Durrës | Durrës | 3 | 205 |

| Total | 315 | 14,234 |

However, in the northernmost districts of Berat and Durrës, the above numbers do not reflect the ethnological distribution, because a large number of students were Orthodox Albanians.[45]

Albanian state (1912-1991)

When Albania was created in 1912, the educational rights of the Greek communities in Albanian territory were granted by the Protocol of Corfu (1914) and with the statement of Albania's representatives in the League of Nations (1921). However, under a policy of assimilation, the Greek schools (there were over 360 until 1913) were gradually forced to close and Greek education was virtually eliminated by 1934. Following the intervention by the League of Nations, a limited number of schools, only those inside the "official minority zones", were reopened.[27][46]

During the years of the communist regime, Greek education was also limited to the so-called "minority zone", in parts of the districts of Gjirokastër, Delvina and Sarande, and even then pupils were taught only Albanian history and culture at the primary level.[9] If a few Albanian families moved into a town or village, the minority's right to be educated in Greek and publish in Greek newspapers was revoked.[16]

Post cold war period (1991-present)

One of the major issues between the Albanian government and the Greek minority in Albania is that of education and the need for more Greek-language schools, due to overcrowded classrooms and unfulfilled demand. In addition, the Greek minority remands that Greek language education be made available outside the "official minority zones". In 2006, the establishment of a Greek-language university in Gjirokastër was agreed upon after discussions between the Albanian and Greek government.[47] Also in 2006, after years of unanswered demands by the local community, a private Greek-language school opened in the town of Himarë,[48] at the precise location where the Orthodox missionary Cosmas the Aetolian founded the Acroceraunian School.[49] The school currently has five teachers and 115 pupils.

Benefaction

A number of people from the prosperous Northern Epirote diaspora of the 18th-19th centuries made significant contributions not only to their homeland, but also to the Greek state and to the Greek world under Ottoman Turkish domination. They donated fortunes for the construction of educational, cultural and social institutions. The Sinas family supported the expansion of the University of Athens and sponsored the foundation of the National Observatory. Ioannis Pangas from Korcë gave all of his wealth for educational purposes in Greece.[46] The Zappas brothers, Evangelos and Konstantinos, endowed Athens with an ancient Greek-style marble stadium (the Kallimarmaro) that has hosted Olympic Games in 1870,[50] 1875, 1896, 1906 and 2004, and the Zappeion exhibition center. The Zappas brothers also founded a number of hospitals and schools in Athens and Constantinople.[3] Christakis Zografos in the Ottoman capital offered vast amounts of money for the establishments of two Greek schools (one for boys, known as Zographeion Lyceum, as well as one for girls), and a hospital.[51]

Organizations

Albania

During the years of communist rule, any form of organization by minorities was prohibited.[52] In 1991, when the communist regime collapsed, the political organization Omonoia (Greek: Ομόνοια) was founded, in the town of Dervican by representatives of the Greek minority. The organization has four affiliates, in Sarandë, Delvinë, Gjirokastër and Tirana, and sub-sections in Korçë, Vlorë and Përmet. Its leading forum is the General Council consisting of 45 members, which is elected by the General Conference held every two years.[53]

The Chair of Omonoia called for the autonomy of Northern Epirus in 1991, on the basis that the rights of the minority under the Albanian constitution were highly precarious. This proposal was rejected and thereby spurred the organization's radical wing to "call for Union with Greece".[52]

Omonoia was banned from the parliamentary elections of March 1991 on the grounds that it violated an Albanian law forbidding the "formation of parties on a religious, ethnic and regional basis". This situation was contested during the following elections on behalf of Omonoia by the Unity for Human Rights Party - a party which represents the Greek minority in the Albanian parliament. Omonoia still exists as an umbrella social and political organization, and represents approximately 100,000 to 150,000 ethnic Greeks.[27]

Omonoia has been the center of more than one political controversy in Albania. A major political controversy erupted in 1994 when five ethnic Greek members of Omonoia were arrested, investigated, and tried for treason. Their arrest was substantially marred by procedural shortcomings in the search of their homes and offices, their detention, and their trial. None of the arrestees had access to legal counsel during their initial detention. Four of the five ethnic Greek members of Omonoia stated that, during their detention, authorities subjected them to physical and psychological pressure, including beatings, sleep deprivation, and threats of torture. The Albanian Government rejected these claims. The five ethnic Greeks also complained of lack of access to their families during the first 3 months of their 4-month investigation. During their trial, a demonstration by a group of about 100 Greek lawyers, journalists, and ethnic Greek citizens of Albania took place outside the courthouse. The Albanian Police violently broke up the protest and detained about 20 lawyers and journalists. The members of Omonoia were eventually sentenced to 6 to 8 year prison terms, which were subsequently reduced on appeal.[20][54]

North America

The Panepirotic Federation of America (Greek: Πανηπειρωτική Ομοσπονδία Αμερικής) was founded in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1942, by Greek immigrants from Epirus (both from the Greek and Albanian part). One of the organization's main goals has been the protection of the human rights of the Greek minority in Albania[55] and to call on the Albanian Government to enhance its full acceptance within the community of responsible nations by restoring to the Greek minority its educational, religious, political, linguistic and cultural rights due them under bilateral and international agreements signed by Albania's representatives since the country was created in 1913, including the right to declare their ethnic and religious affiliation in a census monitored by international observers.[56]

The organization played and still plays essential part in promoting the Northern Epirote issue. It is claimed that the Albanian-American relations worsened in 1946 due to successful lobbying by the Panepirotic Federation in promoting the Northern Epirote issue among American political circles. Albanian leader Enver Hoxha, opposing the restoration of an autonomous Northern Epirus, decided not to pursue diplomatic relations with the United States.[57]

Australia

The Panepirotic Federation of Australia (Greek: Πανηπειρωτική Ομοσπονδία Αυστραλίας) was founded in 1982 as a Federation of various organizations representing migrants who originated from the region of Epirus throughout Australia. It is known for its dedication to the maintenance and development of Epirotic culture in Australia, its passionate championing of the rights of the Greek minority of Northern Epirus, and plays a prominent role in the life of the Greek community in Australia. It has donated over one million dollars to works of a charitable and philanthropic nature for the Greeks of Northern Epirus. It is also affiliated with the World Council of Epirotes Abroad and the World Council of Hellenes Abroad.

The Panepirotic Federation of Australia's former president, Mr Petros Petranis has notably completed a study of Epirotic migration to Australia, which is titled "Epirots in Australia" (Greek: Οι Ηπειρώτες στην Αυστραλία), published by the National Centre for Hellenic Studies, LaTrobe University, in 2004.

Notable people

For the ancient Greeks who lived in the region, see Chaones.

Academics

- Charles Moskos (1934–2008), sociologist and professor.

- Dimitris Nanopoulos (1948- ), world-renowned physicist, of a Northern Epirotian[58] descent.

- Vasileios Ioannidis (1869–1963), theologian.

- Tasos Vidouris (1888–1967), professor and poet.

Literature & Art

- Stavrianos Vistiaris, 16th century poet.

- Kosmas Thesprotos (1780–1852)

- Konstantinos Skenderis, journalist, author and member of the Greek Parliament (1915–1917) for the Korytsa Prefecture.

- Theophrastos Georgiadis (1885–1973), author.

- Katina Papa (1903–1959), author.

- Michael Vasileiou, entrepreneur and scholar.

- Theodosios Gousis, painter.

- Konstantinos Kalymnios, poet.

- Takis Tsiakos (1909–1997), poet.

- Rita Wilson, actress and producer.

- Laert Vasili, actor and director.

Military/Resistance

- Konstantinos Lagoumitzis (1781–1827), revolutionary.

- Kyriakoulis Argyrokastritis (-1828), revolutionary.

- Michail Spyromilios (1800–1880), army General, military advisor and politician.

- Zachos Milios (1805–1860) army officer.

- Ioannis Poutetsis (-1912) revolutionary.

- Spyros Spyromilios (1864–1930) Gendarmerie officer.

- Dimitrios Doulis (1865–1928), army officer, minister of military affairs of the Autonomous Rep. of Northern Epirus.

- Nikolaos Dailakis ( -1941) revolutionary of the Macedonian Struggle.

- Vasilios Sahinis (1897–1943), leader of the Northern Epirote resistance (1942–1943).

Philanthropy

- Alexandros Vasileiou (1760–1818)

- Ioannis Dombolis (1769–1849)

- Apostolos Arsakis (1792–1874)

- Evangelis Zappas (1800–1865)

- Konstantinos Zappas (1814–1892)

- Ioannis Pangas (1814–1895)

- Georgios Sinas (1783–1856)

- Simon Sinas (1810–1876)

- Christakis Zografos (1820–1896)

Politics

- Thanasis Vagias (1765–1834) counselor of Ali Pasha

- Kyriakos Kyritsis lawyer and member of the Greek Parliament (1915–1917) for the Argyrokastron Prefecture.

- Petros Zappas, member of the Greek Parliament (1915–1917) for the Argyrokastron Prefecture.

- Georgios Christakis-Zografos (1863–1920), diplomat, president of the Provisional Government of Northern Epirus (1914).

- Themistoklis Bamichas (1875–1930), politician.

- Mihal Kasso, politician.

- Spiro Koleka (1908–2001), long-serving member of the Politburo of the Party of Labour of Albania, one of the few members of the Greek minority serving in the Socialist People's Republic of Albania political system.[59]

- George Tenet, former Director of CIA, of Himariot origin.

- Vasil Bollano (Vasileios Bollanos) present chairman of Omonoia.

- Spiro Ksera (Spyros Xeras), former prefect of Gjirokastër County and member of the Albanian cabinet.

- Simon Stefani, Chairman of the Assembly of the Republic of Albania (1978–1982).

Religion

- Sophianos (-1711), bishop of Dryinoupolis and scholar.

- Nektarios Terpos, Aromanian (end 17th-18th century) priest and author.

- Gavriel Konstantinidis, 18th century, monk, founder of the printing-house in Moscopole (1731).

- Vasileios of Dryinoupolis (1858–1936), bishop and member of the provisional government of Northern Epirus (1914).

- Ioakeim Martianos (1875–1955), bishop and author.

- Panteleimon Kotokos (1890–1969), bishop of Gjirokastër (1937–1941).

Sports

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- Pyrros Dimas, Greek weight-lifer, Olympic medalist, born in Himarë

- Panajot Pano (1939–2010), footballer of Greek origin, born in Durrës

- Sotiris Ninis, Greek footballer, born in Himarë

- Andreas Tatos, Greek footballer, born in Himarë

- Leonidas Sabanis, Greek weight-lifter, born in Korçë

- Panagiotis Kone, Greek footballer, born in Tirana

See also

- Northern Epirus

- Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

- Protocol of Corfu

- Greeks

- Demographics of Albania

- Death of Aristotelis Goumas

References

- ↑ Pettifer, James (2000). The Greeks the land and people since the war. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-028899-5.

- 1 2 and Migration Policy in Greece. Critical Review and Policy Recommendations. Anna Triandafyllidou. Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Data taken from Greek ministry of Interiors. p. 3 "Greek co ethnics who are Albanian citizens (Voreioepirotes) hold Special Identity Cards for Omogeneis (co-ethnics) (EDTO) issued by the Greek police. EDTO holders are not included in the Ministry of Interior data on aliens. After repeated requests, the Ministry of Interior has released data on the actual number of valid EDTO to this date. Their total number is 189,000."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ruches, Pyrrhus J. (1965). Albania's Captives. Argonaut.

- ↑ Petiffer, James (2001). The Greek Minority in Albania - In the Aftermath of Communism (PDF). Surrey, UK: Conflict Studies Research Centre. p. 7. ISBN 1-903584-35-3.

- ↑ ,Miranda Vickers, James Pettifer (1997). Albania: from anarchy to a Balkan identity. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 187. ISBN 0-7156-3201-9.

- ↑ Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands, Borderlands A History of Northern Epirus-Southern Albania. Gerald Duckworth, Limited. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7156-3201-7.

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Greece

- ↑ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Albania

- 1 2 3 4 5 James Pettifer.The Greek Minority in Albania In the Aftermath of Communism. Paper prepared for the British MoD, Defence Academy, 2001. ISBN 1-903584-35-3.

- ↑ US Department of State, 2008 Human Rights Report: Albania

- ↑ Nußberger Angelika, Wolfgang Stoppel (2001). "Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien)" (PDF) (in German). p. 21: Universität Köln

- ↑ https://books.google.co.nz/books?id=FFcMAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA587&lpg=PA587&dq=Greeks+in+Albania+numbers&source=bl&ots=9EuUboE-NO&sig=V1jnh2nywOzBskU1DnDOU4LzKY8&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0CDgQ6AEwBDgKahUKEwiFm53o5ubGAhWo2qYKHWiFAhA#v=onepage&q=Greeks%20in%20Albania%20numbers&f=false

- ↑ http://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/albania/northern-epiros-greek-minority-southern-albania

- ↑ http://www.balkaneu.com/omonias-census-greek-minority-constitutes-10-population-albania/

- ↑ http://www.voltairenet.org/IMG/pdf/Greek_minority_in_Albania.pdf

- 1 2 Vance, Charles; Paik, Yongsun (2006). Managing a Global Workforce Challenges and Opportunities in International Human Resource Management. M.E. Sharpe. p. 682. ISBN 978-0-7656-2016-3.

- ↑ Kalekin-Fishman, Devorah; Pitkänen, P. (2006). Multiple Citizenship as a Challenge to European Nation-States. Sense Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 978-90-77874-86-8.

- ↑ Sasin, edited by Edmundo Murrugarra, Jennica Larrison, Marcin (2010). Migration and poverty : toward better opportunities for the poor. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8213-8436-7.

- ↑ McAdam, Marika (2009). Western Balkans (2nd ed.). Footscray, Vic.: Lonely Planet. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-74104-729-5.

- 1 2 U.S. Department of State - Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 1994:Albania

- ↑ Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities: Second Opinion on Albania 29 May 2008. Council of Europe: Secretariat of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- ↑ http://lajmifundit.al/2013/12/rama-ne-tv-grek-minoriteti-helen-sdo-te-kete-probleme-ne-shqiperi/

- ↑ http://eu.greekreporter.com/2014/08/01/albania-edi-rama-acknowledges-greeks-of-himara/

- ↑ Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity. Miranda Vickers, James Pettifer. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1997. ISBN 1-85065-290-2 "...in practise many villages of ethnic Greeks were unable to obtain minority classification because a few Albanians also lived there.

- 1 2 3 Contested Spaces and Negotiated Identities in Dhermi/Drimades of Himare/Himara area, Southern Albania. Nataša Gregorič Bon. Nova Gorica 2008.

- 1 2 Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands, Borderlands A History of Northern Epirus-Southern Albania. Gerald Duckworth, Limited. ISBN 978-0-7156-3201-7.

- 1 2 3 4 King, Russell; Mai, Nicola; Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (2005). The New Albanian Migration. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903900-78-9.

- ↑ Balkan Identities: Nation and Memory. Marii︠a︡ Nikolaeva Todorova. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2004. ISBN 1-85065-715-7

- ↑ Vickers, Miranda. The Greek Minority in Albania – Current Tensions. In Balkan Series, January 2010 http://kms1.isn.ethz.ch/serviceengine/Files/ISN/111787/ipublicationdocument_singledocument/4c536356-fe1d-4409-b352-0b01de1447b3/en/2010_01_$Balkan+Series+0110+WEB.pdf

- ↑ Fassmann, Heinz; Reeger, Ursula; Sievers, Wiebke (2009). Statistics and Reality Concepts and Measurements of Migration in Europe. Amsterdam University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-90-8964-052-9.

- ↑ Migration and Migration Policy in Greece. Critical Review and Policy Recommendations. Anna Triandafyllidou. Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Data taken from Greek ministry of Interiors.

- ↑ The question of Northern Epirus at the Peace Conference. Pan-Epirotic Union of America. Nicolas J. Cassavetis. Oxford University Press American Branch. 1919.

- ↑ Declaration of the Northern Epirotes from the districts of Korytsa and Kolonia. Pan-Epirotic Union of America.

- ↑ Tamis, Anastasios M. (2005). The Greeks in Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54743-7.

- 1 2 Appendix A. History & Diatopy of Greek. The story of pu: The grammaticalisation in space and time of a Modern Greek complementiser. December 1998. University of Melbourne.Nick Nicholas.

- ↑ Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 2002. ISBN 978-0-313-32384-3.

- ↑ Plantenga, Bart (2004). Yodel-ay-ee-oooo The Secret History of Yodeling Around the World. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-93990-4.

- ↑ Journal of the American Musicological Society. American Musicological Society. 1959. p. 97.

- ↑ Holst-Warhaft, Gail (1992). Dangerous Voices Women's Laments and Greek Literature. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-415-07249-6.

- ↑ Sakellariou, M.V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotikē Athēnōn. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- ↑ Hetzer, Armin (1984). Geschichte des Buchhandels in Albanien Prolegomena zu einer Literatursoziologie. In Kommission bei O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-02524-9.

- ↑ Kostantaras, Dean J. (2006). Infamy and revolt the rise of the national problem in early modern Greek thought. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-581-2.

- ↑ Albania's Captives. P. Ruches. Argonaut, 1965. P. 51

- ↑ Ruches, Pyrros (1965). "Albania's Captives". Chicago, USA: Argonaut: 52–53.

- ↑ Sakellariou, M.V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotikē Athēnōn. p. 309. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- 1 2 Greece of Tomorrow. George H. Chase. READ BOOKS, 2007. ISBN 1-4067-0758-9

- ↑ Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Albania, 2006. U.S. Department of State.

- ↑ Gregorič 2008: p. 68

- ↑ Tourist Guide of Himarë. Bashkia e Himarës.

- ↑ The Modern Olympics, A Struggle for Revival, by David C. Young, p. 44

- ↑ Ruches, Pyrrhus J. (1967). Albanian Historical Folksongs, 1716-1943 A Survey of Oral Epic Poetry from Southern Albania, with Original Texts. Argonaut.

- 1 2 Working Paper. Albanian Series. Gender Ethnicity and Landed Property in Albania. Sussana Lastaria-Cornhiel, Rachel Wheeler. September 1998. Land Tenure Center. University of Wisconsin.

- ↑ Report submitted by Albania puruant to article 25, paragraph 1 of the framework convention for the protection of national minorities. ACFR/SR (2001). 26 July 2001.

- ↑ P. Papondakis, The Omonoia Five trial: democracy, ethnic minorities and the future of Albania' - Sudosteuropa, 1996

- ↑ Panepirotic foundation of America

- ↑ http://www.panepirotic.org/html/resolutions.html Resolutions of the Panepirotic Federation of America. June 16, 2007 Worcester, MA

- ↑ Jacques, Edwin E. (1995). The Albanians An Ethnic History from Prehistoric Times to the Present. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-89950-932-7.

- ↑ Από τη Βόρειο Ηπειρο στο Σύμπαν: (in Greek) «Οχι, δεν είμαι Πελοποννήσιος. Γεννήθηκα και μεγάλωσα στην Αθήνα, αλλά είμαι Βορειοηπειρώτης και μάλιστα Βλάχος. Νάκας ήταν το αυθεντικό επώνυμο του παππού μου προτού φύγουμε από την Αλβανία»

- ↑ Pettifer, James; Poulton, Hugh (1994). The Southern Balkans. Minority Rights Group. p. 1994. ISBN 978-1-897693-75-9.

Further reading

- Austin, Robert. Kjellt Engelbrekt, and Duncan M. Perry. “Albania’s Greek Minority”. RFE/RL Research Report. Vol 3 Iss 11. 18 March 1994, pp. 19–24

- Berxolli, Arqile. Sejfi Protopapa, and Kristaq Prifti. “The Greek Minority in the Albanian Republic: A Demographic Study”. Nationalities Papers 22, no.2, (1994)

- Filippatos, James. “Ethnic Identity and Political Stability in Albania: The Human Rights Status of the Greek Minority”, Mediterranean Quarterly, Winter 1999, pp. 132–156

- Gregorič, Nataša. "Contested Spaces and Negotiated Identities in Dhërmi/Drimades of Himarë/Himara area, Southern Albania" (PDF). University of Nova Gorica. Retrieved 2010-08-15.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||