Grayrigg derailment

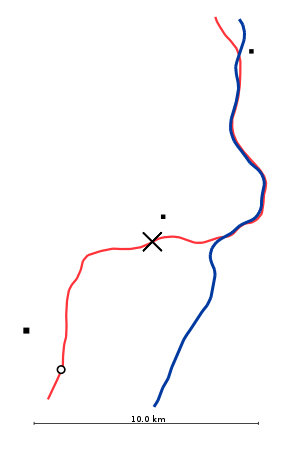

The scene of the accident | |

| Date | 23 February 2007 |

|---|---|

| Time | 20:15 GMT |

| Location | Grayrigg, Cumbria |

| Coordinates | 54°21′25″N 2°39′36″W / 54.357°N 2.660°WCoordinates: 54°21′25″N 2°39′36″W / 54.357°N 2.660°W |

| Country | England |

| Rail line | West Coast Main Line |

| Operator | Virgin Trains |

| Cause | Defective points due to poor maintenance and inspection procedures. |

| Statistics | |

| Trains | 1 |

| Passengers | 105 + 4 crew[1] |

| Deaths | 1 |

| Injuries | 30 serious, 58 minor[1] |

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |

The Grayrigg derailment was a fatal railway accident that occurred at approximately 20:15 GMT on 23 February 2007, just to the south of Grayrigg, Cumbria, in the North West England region of the United Kingdom. The initial conclusion of the accident investigation is that the derailment was caused by a faulty set of points (number 2B) on the Down Main running line, controlled from Lambrigg ground frame. The scheduled inspection on 18 February 2007 had not taken place and the faults had gone undetected.[2] The points which caused the derailment, and points 2A on the opposite line, were removed from the track following the derailment and the line is now welded continuously for 2.2 miles (3.5 km) including the line over the Docker viaduct.

The derailment also brought down the overhead line equipment which had to be replaced. Modern double-line catenary from a single stand was used for this, which reduces the risk of carriages bending if a derailment occurs, for example becoming wedged between the overhead line stanchions as seen in the Southall crash. Although the accident killed far fewer people than some other accidents on the West Coast Main Line, it had a major negative impact on Network Rail's safety record.

Incident

The 17:30 Virgin West Coast Pendolino West Coast Main Line InterCity service from London Euston to Glasgow Central derailed at 20:15 by a faulty set of points almost immediately after crossing the Docker Viaduct (the rear half of the train would still have been crossing the bridge whilst the front derailed at the points).[3] The train was reported to have been travelling at 153 km/h (95 mph), when it was derailed.[4] The train, consisting of unit 390 033 City of Glasgow, which was constructed at Washwood Heath, Birmingham, in 2002, had nine carriages and carried 105 passengers and four staff members.[5]

Passengers said that the carriages of the train began rocking and swaying violently before the train left the rails and careered down an embankment, with the first carriages jack-knifing and most of the train coming to rest in a field. The train was reported as being evacuated around midnight. Emergency crews scanned the train with thermal imagery equipment to make sure there was no one still inside. Up to 500 rescuers attended the scene, along with at least 12 ambulances, at least five fire engines, three Royal Air Force Sea King search and rescue helicopters, the International Rescue Corps, three civilian mountain rescue teams plus RAF Leeming Mountain Rescue Team, and one Merseyside Police helicopter. The rescue operation was hindered by rain, darkness, and access problems caused by the narrow country lanes and muddy fields.[2] Emergency vehicles experienced difficult conditions, needing to be towed by farm vehicles or tractors after becoming bogged down in mud. The train's derailment caused severe damage to the Overhead Line Equipment and tripped the entire circuit between Brock (near Preston) and Tebay resulting in a number of other electric-powered services coming to a halt and all signalling equipment immediately turning to danger (red) in accordance with the system's fail safe design.

Live BBC television coverage at 08:15 the following morning showed that although the whole train had been derailed, the rear carriages were standing nearly vertically on the sleepers and ballast. Standard class, the front five carriages, were the worst affected, and the rear four first class carriages were in better condition. The leading carriage, a driving motor coach, had headed down the embankment, and turned end-for-end as it fell. It was lying on its side at the foot of the embankment. The second carriage had jack-knifed against the first, breaking the coupling, and so had not followed it down the bank. This second carriage came to rest some distance further along the track, at a steep angle with one end in the air. The middle part of the train toppled sideways down the embankment. All the partially friction stir welded carriages remained structurally intact, with damage mainly confined to the crumple zones at their ends. None of the windows broke, and lighting remained in all the carriages. Most injuries occurred in the front two carriages. The driver, who had stayed at the controls (but had little option to move once the accident had started and had no prior indication of derailment), was trapped for about an hour while specialist cutting equipment was used to free him from his cab.[6] The other three members of the crew were in the rear first class section of the train.

Survivors were initially received at Grayrigg Primary School, which had been opened as a Survivor Reception Centre. Hospitals in the area, including some over the Scottish border in Dumfries and Galloway, were put on standby, but not all received patients. According to BBC News, five passengers were admitted to Royal Preston Hospital in a critical condition. Police later released a statement revealing that one passenger, 84-year-old Margaret Masson from Glasgow, had died in hospital. Her funeral took place on 31 March 2007 at Craigton crematorium in Glasgow.[7]

Aftermath

A family liaison centre was set up in Glasgow Central Station for worried relatives.

Within three hours of the derailment the site of the accident had been sealed off with a five-mile cordon. The line was expected to be closed for two weeks, with Virgin Trains saying that the line would not reopen to passenger services until 12 March 2007.[8] The recovery operation was slowed by problems in getting heavy lifting gear to the site which required temporary roads to be constructed.

Sir Richard Branson, Virgin Group chairman, visited the site of the derailment at 11:00 the following morning to comment on the incident. During his news conference at the site he said that he regarded the driver, named as Iain Black from Dumbarton,[9] as a hero, as he had attempted to stop the train and remained in his seat to ensure the safety of passengers.[6] Mr Black left hospital in late March and stated that "I've got to be in the cab to help the train and it never crossed my mind to leave."[9]

Branson also later thanked local residents for their help at the accident site, describing how he "was very impressed to hear how those kind people rallied round, opening their hearts and opening their doors to strangers in distress".[10] Local farmers assisted the emergency services by transporting equipment using quad bikes and four-wheel drive vehicles. Sergeant Jo Fawcett of the Cumbria Constabulary also offered thanks, saying that "There are so many people who have given up their own time to contribute in some way to dealing with the aftermath of the derailment that it would be unfair to name them for fear of missing someone out."[11]

Branson also paid tribute to the Pendolino train, comparing it to a "tank". He also added "If the train had been old stock then the number of injuries and the mortalities would have been horrendous".[12] Several sources also gave their praise due to the fact that the carriages generally stayed intact during the accident.

As a result of the suspicion that faulty points were the cause of the Grayrigg Derailment, Network Rail checked over 700 sets of similar points across the country as a "precautionary measure"[8] saying later that "nothing of concern" had been found.[13]

The operation to remove the train from the site began on the evening of 1 March 2007 with the first carriages moved from the embankment. This allowed passengers' property to be retrieved and gave investigators access to the train interior, which previously had not been possible because it would have been unsafe.[14] The last of the carriages were removed on 4 March 2007 and the A685 road was reopened.[15]

In 2013 the British Transport Police (BTP) posthumously awarded a Chief Constables Commendation to a member of its staff, Jon Ratcliffe, who was at the time of the disaster Media and Marketing Manager for BTP's North Western Area. He received the commendation for his good handling of media enquires in the aftermath of the crash. Jon Ratcliffe died in 2008 following a sudden illness.[16]

Cause

Lambrigg ground frame, 660 yards (600 m) south-west of the accident site, controls two crossovers, each one comprising two sets of points allowing trains to cross from one running line to the other in emergencies or during track maintenance work. These points are used only occasionally, operated locally after a release is obtained from Carlisle power signal box. They are normally locked in the main line "running" position. Early statements by Chief Superintendent Martyn Ripley of British Transport Police suggested that investigations would focus on these points.

Investigations were launched by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch and Her Majesty's Railway Inspectorate.[6] RMT rail union leader Bob Crow said on BBC News that a points failure was responsible for the incident. Experts compared the cause to that of the Potters Bar rail crash in 2002.[8]

On 26 February, an interim report published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch outlined the current progress of the investigation.[5] The report contained a single conclusion, that the immediate cause of the accident was the condition of the stretcher bar arrangement at points 2B at Lambrigg crossover, which resulted in the loss of gauge separation of the point switch blades. The stretcher bars (components that hold the moving blades of the points the correct distance apart) had been found to be disconnected or missing. Of the three bars, one was not in position, another had nuts and bolts missing, and two were fractured. The points in question were facing the direction of travel of the train.

Following the RAIB report, Network Rail released a statement in which its Chief Executive, John Armitt, described how the organisation was "devastated to conclude that the condition of the set of points at Grayrigg caused this terrible accident". He apologised "to all the people affected by the failure of the infrastructure".[17]

The RAIB report noted that the Network Rail New Measurement Train ran over the site on 21 February. This train uses lasers and other instruments to make measurements of the track geometry and other features such as overhead line height and stagger, and the track gauge, twist and cant. It is not used to inspect points, but it does make a video record of the track which can be reviewed later. Commenting on the possibility that the train's video might have been used to detect the points damage and thereby prevent the accident, a Network Rail spokesman said:

The [inspection] train runs at speeds of up to 125 mph, or 95 mph on this stretch. There would be no point somebody watching it at that speed as they wouldn't be able to pick up any faults. It has to be run in super-slow motion to spot faults. The train runs for up to 18 hours a day, seven days a week. It would probably take someone most of the month to watch one day's worth of data. It's not what it's there for. It's a backwards reference tool.

Network Rail admitted it failed to carry out a scheduled visual track inspection in the area on the Sunday before the derailment.

Bob Crow of the RMT union said:

This is shutting the stable door after the horse has well and truly bolted. We argued this train should not replace visual inspections. Inspectors who walk the track are the eyes and ears of the railway. They don't just check the safety of the track, they look at the area surrounding it, check for signs of potential trouble such as gaps in the fence where vandals could get in.

Labour Party Member of Parliament John McDonnell added: "The fact that Network Rail apparently had footage of a missing stretcher bar days before the fatal crash is very worrying."[18]

As part of the investigation by the British Transport Police, three Network Rail employees were arrested and bailed, one in July 2007 and two in November 2007[19] All three were due to answer bail in March 2008 but this was extended until the end of June pending further inquiries.[20] On 9 February 2009, the British Transport Police confirmed that none of the three Network Rail employees arrested in connection with the derailment will be charged following advice from the Crown Prosecution Service.[21]

Subsequent service disruption

Immediately after the accident, all services were suspended and the First ScotRail Sleeper train, the Caledonian Sleeper, was curtailed and passengers transferred to overnight coaches.[22]

The line closure that followed the initial service suspension saw most Virgin services terminate at Preston or Lancaster from the south, with buses to Carlisle and all stations along the route. The only exception was an early-morning and late-evening through service from Carlisle to London and return. This was diesel-hauled via Blackburn and Settle. There were also several non-stop trains from Preston to London Euston. Local services all terminated short but many were able to make their journeys as their destinations were off branches. The Caledonian Sleeper was diverted via the East Coast Main Line, along with freight services, although some were diesel-hauled via Blackburn and Settle.

Trains began running on the line again on 12 March subject to a speed restriction of 80 km/h (50 mph) at the crash site. The first train was the 05:10 Manchester to Glasgow.[23]

Prior incidents

The Grayrigg derailment was not the first British railway accident to feature a train or locomotive named City of Glasgow on the West Coast Mainline. In the Harrow and Wealdstone railway accident on 8 October 1952, the locomotive of the sleeper train from Perth to London Euston, whose crew was responsible for the incident, was Class 8P No. 46242 City of Glasgow.

In the area near the accident, south of Tebay in Cumbria, on 15 February 2004 another fatal incident had occurred, the Tebay rail accident, when four rail workers were killed by a runaway track maintenance trailer.[24] Also close by was a collision on the Lambrigg Crossing on 18 May 1947.[25]

Prosecution

On 13 January 2012, the Office of Rail Regulation announced that Network Rail were to be prosecuted under Section 3(1) of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 for "the company's failure to provide and implement suitable and sufficient standards, procedures, guidance, training, tools and resources for the inspection and maintenance of fixed stretcher bar points". At the first hearing at Lancaster Magistrates' Court on 28 February 2012, Network Rail indicated an intention to plead guilty to the charges.[26] On 4 April 2012, Network Rail were fined a total of £4,118,037 including costs following the court case.[27]

Critical commentary appeared in the media concerning the knighthood awarded to John Armitt in the 2012 New Year Honours for services to engineering and construction. Armitt had been Chief Executive of Network Rail at the time of the Grayrigg derailment, and the family of a victim of the accident criticised the award, which coincidentally was conferred on the same day that Network Rail were prosecuted for the accident.[28]

After a two-week hearing one of the issues Coroner Ian Smith announced that he would be issuing a rule 43 report.[29] The intention of the report is to raise concerns with authorities to prevent similar incidents occurring again.[30]

See also

| Wikinews has related news: Virgin Train crashes in England |

References

- 1 2 "Derailment at Grayrigg 23 February 2007" (PDF). Rail Accident Investigation Branch. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- 1 2 "Rail crash report blames points". BBC News Online. 26 February 2007.

- ↑ "Serious incident in Cumbria – Statement No. 3–24 February 2007" (Press release). Virgin Trains. 24 February 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ↑ "One dead in Cumbria train crash". BBC News Online. 24 February 2007.

- 1 2 "RAIB interim report into a derailment at Grayrigg, Cumbria 23 February 2007" (PDF). Rail Accident Investigation Branch. Note: passenger numbers subsequently revised from 111 to 105 in final report.

- 1 2 3 "Crash inquiry to focus on points". BBC News Online. 24 February 2007.

- ↑ "Rail Victim's Funeral". News & Star. 31 March 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Crash sparks national rail checks". BBC News Online. 24 February 2007.

- 1 2 "Hero train driver tells of ordeal". BBC News Online. 22 March 2007.

- ↑ "Community praised for heroic response". Westmorland Gazette. 2 March 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ↑ "Praise for rail crash site locals". BBC News Online. 6 April 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ↑ "It is a very sad day – Branson". BBC News. 24 February 2007. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ↑ "Network safe, rail bosses insist". BBC News Online. 25 February 2007.

- ↑ "First carriages moved from wreck". BBC News Online. 2 March 2007.

- ↑ "Last rails cars and crane 'shipped out'". Westmorland Gazette. 5 March 2007.

- ↑ http://www.btp.police.uk/latest_news/local_news_north_western/posthumous_commendation.aspx

- ↑ "Network Rail responds to initial RAIB report". Network Rail.

- ↑ "Rail Chiefs Never Watched Broken Rail Vid". Mirror.co.uk. 28 February 2007.

- ↑ "Two men arrested over train crash". BBC News Online. 15 November 2007.

- ↑ "Three rail workers' bail extended". BBC News Online. 26 March 2008.

- ↑ "No charges over fatal rail crash". BBC News Online. 9 February 2009.

- ↑ "Crash leads to travel disruption". BBC News Online. 24 February 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- ↑ "Trains Back on Crash Line". Sky News. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ↑ "Pair jailed for Tebay rail deaths". BBC News Online. 17 March 2006. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ↑ "Ministry of Transport Accident Report Between Grayrigg and Oxenholme, L.M.S.R., May 18, 1947". Railway Gazette. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- ↑ "Network Rail to be prosecuted over Grayrigg crash". BBC News Online. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ↑ "Grayrigg crash: Network Rail fined £4m over death". BBC News Online. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ "Grayrigg crash victim's son 'disgusted' by knighthood". BBC News. 1 March 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ↑ "Grayrigg train crash: Faulty points caused woman's death". Cumbria: BBC News. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Dixon, Rob (8 November 2011). "'Lessons Must Be Learned' From Grayrigg Train Crash Inquest". Sheffield: Irwin Mitchell. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

| ||||||||||