Tidal force

The tidal force is a secondary effect of the force of gravity and is responsible for the tides. It arises because the gravitational force exerted by one body on another is not constant across it; the nearest side is attracted more strongly than the farthest side. Thus, the tidal force is differential. Consider the gravitational attraction of the moon on the oceans nearest to the moon, the solid Earth and the oceans farthest from the moon. There is a mutual attraction between the moon and the solid earth which can be considered to act on its centre of mass. However, the near oceans are more strongly attracted and, since they are fluid, they approach the moon slightly, causing a high tide. The far oceans are attracted less. The attraction on the far-side oceans could be expected to cause a low tide but since the solid earth is attracted (accelerated) more strongly towards the moon, there is a relative acceleration of those waters in the outwards direction. Viewing the Earth as a whole, we see that all its mass experiences a mutual attraction with that of the moon but the near oceans more so than the far oceans, leading to a separation of the two.

In a more general usage in celestial mechanics, the expression 'tidal force' can refer to a situation in which a body or material (for example, tidal water) is mainly under the gravitational influence of a second body (for example, the Earth), but is also perturbed by the gravitational effects of a third body (for example, the Moon). The perturbing force is sometimes in such cases called a tidal force[1] (for example, the perturbing force on the Moon): it is the difference between the force exerted by the third body on the second and the force exerted by the third body on the first.[2]

Explanation

When a body (body 1) is acted on by the gravity of another body (body 2), the field can vary significantly on body 1 between the side of the body facing body 2 and the side facing away from body 2. Figure 2 shows the differential force of gravity on a spherical body (body 1) exerted by another body (body 2). These so-called tidal forces cause strains on both bodies and may distort them or even, in extreme cases, break one or the other apart.[3] The Roche limit is the distance from a planet at which tidal effects would cause an object to disintegrate because the differential force of gravity from the planet overcomes the attraction of the parts of the object for one another.[4] These strains would not occur if the gravitational field were uniform, because a uniform field only causes the entire body to accelerate together in the same direction and at the same rate.

Effects of tidal forces

In the case of an infinitesimally small elastic sphere, the effect of a tidal force is to distort the shape of the body without any change in volume. The sphere becomes an ellipsoid with two bulges, pointing towards and away from the other body. Larger objects distort into an ovoid, and are slightly compressed, which is what happens to the Earth's oceans under the action of the Moon. The Earth and Moon rotate about their common center of mass or barycenter, and their gravitational attraction provides the centripetal force necessary to maintain this motion. To an observer on the Earth, very close to this barycenter, the situation is one of the Earth as body 1 acted upon by the gravity of the Moon as body 2. All parts of the Earth are subject to the Moon's gravitational forces, causing the water in the oceans to redistribute, forming bulges on the sides near the Moon and far from the Moon.[6]

When a body rotates while subject to tidal forces, internal friction results in the gradual dissipation of its rotational kinetic energy as heat. If the body is close enough to its primary, this can result in a rotation which is tidally locked to the orbital motion, as in the case of the Earth's moon. Tidal heating produces dramatic volcanic effects on Jupiter's moon Io. Stresses caused by tidal forces also cause a regular monthly pattern of moonquakes on Earth's Moon.

Tidal forces contribute to ocean currents, which moderate global temperatures by transporting heat energy toward the poles. It has been suggested that in addition to other factors, harmonic beat variations in tidal forcing may contribute to climate changes. However, no strong link has been found to date.[7]

Tidal effects become particularly pronounced near small bodies of high mass, such as neutron stars or black holes, where they are responsible for the "spaghettification" of infalling matter. Tidal forces create the oceanic tide of Earth's oceans, where the attracting bodies are the Moon and, to a lesser extent, the Sun. Tidal forces are also responsible for tidal locking, tidal acceleration, and tidal heating.

Mathematical treatment

For a given (externally generated) gravitational field, the tidal acceleration at a point with respect to a body is obtained by vectorially subtracting the gravitational acceleration at the center of the body (due to the given externally generated field) from the gravitational acceleration (due to the same field) at the given point. Correspondingly, the term tidal force is used to describe the forces due to tidal acceleration. Note that for these purposes the only gravitational field considered is the external one; the gravitational field of the body (as shown in the graphic) is not relevant. (In other words, the comparison is with the conditions at the given point as they would be if there were no externally generated field acting unequally at the given point and at the center of the reference body. The externally generated field is usually that produced by a perturbing third body, often the Sun or the Moon in the frequent example-cases of points on or above the Earth's surface in a geocentric reference frame.)

Tidal acceleration does not require rotation or orbiting bodies; for example, the body may be freefalling in a straight line under the influence of a gravitational field while still being influenced by (changing) tidal acceleration.

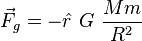

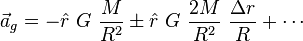

By Newton's law of universal gravitation and laws of motion, a body of mass m at distance R from the center of a sphere of mass M feels a force  ,

,

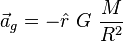

equivalent to an acceleration  ,

,

where  is a unit vector pointing from the body M to the body m (here, acceleration from m towards M has negative sign).

is a unit vector pointing from the body M to the body m (here, acceleration from m towards M has negative sign).

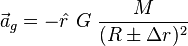

Consider now the acceleration due to the sphere of mass M experienced by a particle in the vicinity of the body of mass m. With R as the distance from the center of M to the center of m, let ∆r be the (relatively small) distance of the particle from the center of the body of mass m. For simplicity, distances are first considered only in the direction pointing towards or away from the sphere of mass M. If the body of mass m is itself a sphere of radius ∆r, then the new particle considered may be located on its surface, at a distance (R ± ∆r) from the centre of the sphere of mass M, and ∆r may be taken as positive where the particle's distance from M is greater than R. Leaving aside whatever gravitational acceleration may be experienced by the particle towards m on account of m's own mass, we have the acceleration on the particle due to gravitational force towards M as:

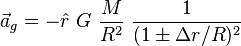

Pulling out the R2 term from the denominator gives:

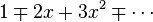

The Maclaurin series of  is

is  which gives a series expansion of:

which gives a series expansion of:

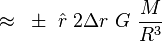

The first term is the gravitational acceleration due to M at the center of the reference body  , i.e., at the point where

, i.e., at the point where  is zero. This term does not affect the observed acceleration of particles on the surface of m because with respect to M, m (and everything on its surface) is in free fall. When the force on the far particle is subtracted from the force on the near particle, this first term cancels, as do all other even-order terms. The remaining (residual) terms represent the difference mentioned above and are tidal force (acceleration) terms. When ∆r is small compared to R, the terms after the first residual term are very small and can be neglected, giving the approximate tidal acceleration

is zero. This term does not affect the observed acceleration of particles on the surface of m because with respect to M, m (and everything on its surface) is in free fall. When the force on the far particle is subtracted from the force on the near particle, this first term cancels, as do all other even-order terms. The remaining (residual) terms represent the difference mentioned above and are tidal force (acceleration) terms. When ∆r is small compared to R, the terms after the first residual term are very small and can be neglected, giving the approximate tidal acceleration  (axial) for the distances ∆r considered, along the axis joining the centers of m and M:

(axial) for the distances ∆r considered, along the axis joining the centers of m and M:

-

(axial)

(axial)

When calculated in this way for the case where ∆r is a distance along the axis joining the centers of m and M,  is directed outwards from to the center of m (where ∆r is zero).

is directed outwards from to the center of m (where ∆r is zero).

Tidal accelerations can also be calculated away from the axis connecting the bodies m and M, requiring a vector calculation. In the plane perpendicular to that axis, the tidal acceleration is directed inwards (towards the center where ∆r is zero), and its magnitude is  (axial)

(axial) in linear approximation as in Figure 2.

in linear approximation as in Figure 2.

The tidal accelerations at the surfaces of planets in the Solar System are generally very small. For example, the lunar tidal acceleration at the Earth's surface along the Moon-Earth axis is about 1.1 × 10−7 g, while the solar tidal acceleration at the Earth's surface along the Sun-Earth axis is about 0.52 × 10−7 g, where g is the gravitational acceleration at the Earth's surface. Hence the tide-raising force (acceleration) due to the Sun is about 45% of that due to the Moon.[9] The solar tidal acceleration at the Earth's surface was first given by Newton in the Principia.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "On the tidal force", I N Avsiuk, in "Soviet Astronomy Letters", vol.3 (1977), pp. 96–99

- ↑ See p.509 in "Astronomy: a physical perspective", M L Kutner (2003).

- ↑ R Penrose (1999). The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics. Oxford University Press. p. 264. ISBN 0-19-286198-0.

- ↑ Thérèse Encrenaz; J -P Bibring; M Blanc (2003). The Solar System. Springer. p. 16. ISBN 3-540-00241-3.

- ↑ R. S. MacKay; J. D. Meiss (1987). Hamiltonian Dynamical Systems: A Reprint Selection. CRC Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-85274-205-3.

- ↑ Rollin A Harris (1920). The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge 26. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. pp. 611–617.

- ↑ "Millennial Climate Variability: Is There a Tidal Connection?".

- ↑ "Inseparable galactic twins". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ↑ The Admiralty (1987). Admiralty manual of navigation 1. The Stationery Office. p. 277. ISBN 0-11-772880-2., Chapter 11, p. 277

- ↑ Newton, Isaac (1729). The mathematical principles of natural philosophy 2. p. 307. ISBN 0-11-772880-2., Book 3, Proposition 36, Page 307 Newton put the force to depress the sea at places 90 degrees distant from the Sun at "1 to 38604600" (in terms of g), and wrote that the force to raise the sea along the Sun-Earth axis is "twice as great", i.e. 2 to 38604600, which comes to about 0.52 × 10−7 g as expressed in the text.

External links

- Gravitational Tides by J. Christopher Mihos of Case Western Reserve University

- Audio: Cain/Gay – Astronomy Cast Tidal Forces – July 2007.

- Gray, Meghan; Merrifield, Michael. "Tidal Forces". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- "Pau Amaro Seoane MODEST working group 4 "Tidal disruption of a star by a massive black hole"". Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- Myths about Gravity and Tides by Mikolaj Sawicki of John A. Logan College and the University of Colorado.