Cursive script (East Asia)

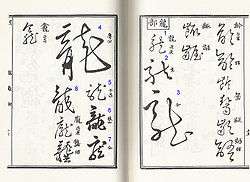

Cursive script (simplified Chinese: 草书; traditional Chinese: 草書; pinyin: cǎoshū), often mistranslated as Grass script (see Names below), is a style of Chinese calligraphy. Cursive script is faster to write than other styles, but difficult to read for those unfamiliar with it. It functions primarily as a kind of shorthand script or calligraphic style. People who can read standard or printed forms of Chinese may not be able to comprehend this script at all.

Names

The character 書 (shū) means script in this context, and the character 草 (cǎo) means quick, rough or sloppy. Thus, the name of this script is literally "rough script" or "sloppy script". The same character 草 (cǎo) appears in this sense in the noun "rough draft" (草稿, cǎogǎo), and the verb "to draft [a document or plan]" (草擬, cǎonǐ). The other, indirectly related, meaning of the character 草 (cǎo) is grass, which has led to the mistranslation "grass script".

History

Cursive script originated in China during the Han dynasty through the Jin period, in two phases. First, an early form of cursive developed as a cursory way to write the popular and not yet mature clerical script. Faster ways to write characters developed through four mechanisms: omitting part of a graph, merging strokes together, replacing portions with abbreviated forms (such as one stroke to replace four dots), or modifying stroke styles. This evolution can best be seen on extant bamboo and wooden slats from the period, on which the use of early cursive and immature clerical forms is intermingled. This early form of cursive script, based on clerical script, is now called zhāngcǎo (章草), and variously also termed ancient cursive, draft cursive or clerical cursive in English, to differentiate it from modern cursive (今草 jīncǎo). Modern cursive evolved from this older cursive in the Wei Kingdom to Jin dynasty with influence from the semi-cursive and standard styles.

Styles

Beside zhāngcǎo and the "modern cursive", there is the "wild cursive" (Chinese: 狂草; pinyin: kuángcǎo, Japanese kyōsō) which is even more cursive and difficult to read. When it was developed by Zhang Xu and Huaisu in the Tang dynasty, they were called Dian Zhang Zui Su (crazy Zhang and drunk Su, 顛張醉素). Cursive, in this style, is no longer significant in legibility but rather in artistry.

Cursive scripts can be divided into the unconnected style (Chinese (S) and Japanese 独草, Chinese (T) 獨草, pinyin dúcǎo, romaji dokusō) where each character is separate, and the connected style (Chinese (S) 连绵, Chinese (T) 連綿, Japanese 連綿体, pinyin liánmián, romaji renmentai) where each character is connected to the succeeding one.

Derived characters

Many of the simplified Chinese characters are modeled on the printed forms of the cursive forms of the corresponding characters (simplified Chinese: 草书楷化; traditional Chinese: 草書楷化; pinyin: cǎoshūkǎihuà).

Cursive script forms of Chinese characters are also the origin of the Japanese hiragana script, which developed from cursive forms of the man'yōgana script. In Japan, cursive script was considered to be suitable for women, and was called women’s script (女手 onnade), whereas the clerical style was considered to be suitable for men, and was called men’s script (男手 otokode).

Notable calligraphers

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chinese cursive script. |

- Wang Xizhi

- Wang Xianzhi

- Zhang Zhi, sage of Cursive Script

- Zhang Xu

- Huaisu

- Wen Zhengming

- Yu Youren

- Lin Sanzhi

References

- The Art of Japanese Calligraphy, 1973, author Yujiro Nakata, publisher Weatherhill/Heibonsha, ISBN 0-8348-1013-1.

- Qiu Xigui Chinese Writing (2000). Translation of 文字學概要 by Gilbert L. Mattos and Jerry Norman. Early China Special Monograph Series No. 4. Berkeley: The Society for the Study of Early China and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 1-55729-071-7.

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||