Googie architecture

Googie architecture is a form of modern architecture, a subdivision of futurist architecture influenced by car culture, jets, the Space Age, and the Atomic Age.[1] Originating in Southern California during the late 1940s and continuing approximately into the mid-1960s, Googie-themed architecture was popular among motels, coffee houses and gas stations. The school later became widely known as part of the Mid-Century modern style, elements of which represent the populuxe aesthetic,[2][3] as in Eero Saarinen's TWA Flight Center. The term "Googie" comes from a now defunct coffee shop and cafe built in West Hollywood[4] designed by John Lautner.[5] Similar architectural styles are also referred to as Populuxe or Doo Wop.[6][7]

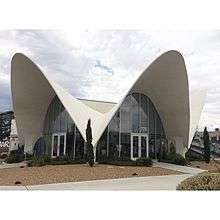

Features of Googie include upswept roofs, curvaceous, geometric shapes, and bold use of glass, steel and neon. Googie was also characterized by Space Age designs symbolic of motion, such as boomerangs, flying saucers, atoms and parabolas, and free-form designs such as "soft" parallelograms and an artist's palette motif. These stylistic conventions represented American society's fascination with Space Age themes and marketing emphasis on futuristic designs. As with the Art Deco style of the 1930s, Googie became less valued as time passed, and many buildings in this style have been destroyed. Some examples have been preserved, though, such as the oldest McDonald's stand (located in Downey, California) that was put on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

Origins

The origin of the name Googie dates to 1949, when architect John Lautner designed the West Hollywood coffee shop Googies, which had distinct architectural characteristics.[8] The name "Googie" had been a family nickname of Lillian K. Burton, the wife of the original owner, Mortimer C. Burton.[9][10]

Googies was located at the corner of Sunset Boulevard and Crescent Heights in Los Angeles but was demolished in 1989.[11] The name Googie became a rubric for the architectural style when editor Douglas Haskell of House and Home magazine and architectural photographer Julius Shulman were driving through Los Angeles one day. Haskell insisted on stopping the car upon seeing Googies and proclaimed "This is Googie architecture."[8] He popularized the name after an article he wrote appeared in a 1952 edition of House and Home magazine.[12][13]

Though Haskell coined the term Googie and was an advocate of modernism, he did not appreciate the Googie aesthetic. In his article he used the fictional Professor Thrugg’s overly-effusive praise to mock Googie, at the same time lampooning Hollywood, which he felt informed the aesthetic.[14]

History

Googie's beginnings are with the Streamline Moderne architecture of the 1930s.[15] Alan Hess, one of the most knowledgeable writers on the subject, writes in Googie: Ultra Modern Road Side Architecture that mobility in Los Angeles during the 1930s was characterized by the initial influx of the automobile and the service industry that evolved to cater to it. With car ownership increasing, cities no longer had to be centered on a central downtown but could spread out to the suburbs, where business hubs could be interspersed with residential areas. The suburbs offered less congestion by offering the same businesses, but accessible by car. Instead of one main store downtown, businesses now had multiple stores in suburban areas. This new trend required owners and architects to develop a visual imagery so customers would recognize it from the road. This modern consumer architecture was based on communication.[16]

The new smaller suburban drive-in restaurants were essentially architectural signboards advertising the business to vehicles on the road. This was achieved by using bold style choices, including large pylons with elevated signs, bold neon letters and circular pavilions.[17] Hess writes that because of the increase in mass production and travel during the 1930s, Streamline Moderne became popular because of the high energy silhouettes its sleek designs created. These buildings featured rounded edges, large pylons and neon lights, all symbolizing, according to Hess, "invisible forces of speed and energy", that reflect the influx of mobility that cars, locomotives and zeppelins brought.[18]

Streamline Moderne, much like Googie, was styled to look futuristic to signal the beginning of a new era – that of the automobile and other technologies. Drive-in services such as diners, movie theaters and gas stations built with the same principles developed to serve the new American city.[18] Drive-ins had advanced car-oriented architectural design, as they were built with an expressive utilitarian style, circular and surrounded by a parking lot, allowing all customers equal access from their cars.[19] These developments in consumer oriented design set the stage for Googie during the 1950s, since during the 1940s World War II and rationing caused a pause of development because of the imposed frugality on the American public.

The prosperous 1950s, however, celebrated its affluence with optimistic designs. The development of nuclear power and the reality of spaceflight captivated the public’s imagination of the future.[20] Googie architecture exploited this trend by incorporating energy into its design with elements such as the boomerang, diagonals, atomic bursts and bright colors.[21] According to Hess, commercial architecture was influenced by the desires of the mass audience.[22] The public was captivated by rocket ships and nuclear energy, so, in order to draw their attention, architects used these as motifs in their work. Buildings had been used to catch the attention of motorists since the invention of the car, but during the 1950s the style became more widespread.

The identity of the first architect to practice in the style is often disputed, though Wayne McAllister was one early and influential architect in starting the style with his 1949 Bob's Big Boy restaurant in Burbank.[23] McAllister got his start designing fashionable restaurants in Southern California which led to a series of Streamline Moderne drive-ins during the 1930s; though he did not have formal training as an architect, he had been offered a scholarship at the architecture school at the University of Pennsylvania because of his skill.[24] McAllister developed a brand for coffee shop chains by developing a style for each client – which also allowed customers to easily recognize a store from the road.[25]

Along with McAllister, the prolific Googie architects included John Lautner, Douglas Honnold and the team of Louis Armet and Eldon Davis of Armet & Davis firm, which they founded in 1947.[4] Also instrumental in developing the style was designer Helen Liu Fong, a member of the firm of Armet and Davis. Joining the firm during 1951, she created such Googie interiors as those of the Johnie's Coffee Shop on Wilshire Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue, the first Norms Restaurant,[26] and the Holiday Bowl on Crenshaw Boulevard.

America's interest in spaceflight had a significant influence on the unique style of Googie architecture. During the 1950s, space travel became a reality for the first time in history. During 1957 the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the first human-made satellite to achieve Earth orbit. The Soviet Union then launched Vostok 1 carrying the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into Earth orbit during 1961. The Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations made competing with the Soviets for dominance in space a national priority of considerable urgency and importance. This marked the beginning of the so-called "Space Race".

Googie style signs usually boast sharp and bold angles, which suggest the aerodynamic features of a rocket ship. Also, at the time, the unique architecture was a form of architectural expressionism, as rockets were technological novelties at the time.

Characteristics

Cantilevered structures, acute angles, illuminated plastic paneling, freeform boomerang and artist's palette shapes and cutouts, and tailfins on buildings marked Googie architecture, which was contemptible to some architects of then-current High Art Modernism, but had defenders during the post-Modern period at the end of the 20th century. The common elements that generally distinguish Googie from other forms of architecture are:

- Roofs sloping at an upward angle: This is the one particular element in which architects were creating a unique structure. Many Googie style coffee shops, and other structures, have a roof that appears to be 2⁄3 of an inverted obtuse triangle. A great example of this is the famous, but now closed, Johnie's Coffee Shop on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles.

- Starbursts: Starbursts are an ornament that is common with the Googie style, showing its Space Age and whimsical influences. Perhaps the most notable example of the starburst appears on the "Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas" sign, which has now become famous. The ornamental design is in the form of, as Hess writes, "a high-energy explosion".[27] This shape is an example of non-utilitarian design, as the star shape has no actual function but merely serves as a design element.

The boomerang shape was another design element that captured movement. It was used structurally in place of a pillar or aesthetically as a stylized arrow. Hess writes that the boomerang was a stylistic rendering of a directional energy field.[28]

Editor Douglas Haskell described the abstract Googie style, saying that "If it looks like a bird, this must be a geometric bird."[29] Also, the buildings must appear to defy gravity, as Haskell noted: "...whenever possible, the building must hang from the sky".[29] Haskell's third tenet for Googie was that it have more than one theme—more than one structural system.[29] Because of its need to be noticed from moving automobiles along the commercial strip, Googie was not a style noted for its subtlety.

One of the more famous Googie buildings is the Theme Building at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), designed by James Langenheim of Pereira and Luckman and built during 1961.

One of the remaining Googie-styled drive-in restaurants, Harvey's Broiler (Paul Clayton, 1958), later Johnie's Broiler in Downey, California, was partially demolished in 2006. However, through the efforts of citizens, the city of Downey, and historic preservationists, the structure was rebuilt and reopened in 2009 as a Bob's Big Boy restaurant.

Another remaining example of Googie architecture still in operation is the main terminal at Washington Dulles International Airport, designed by Eero Saarinen in 1958. The terminal exemplifies the dramatic roof slope, large windows, and generous use of concrete, somewhat similar to Saarinen's TWA Flight Center.

Districts

Classic locations for Googie style buildings are Miami Beach, Florida, where secondary commercial structures were adapted from the resort style of Morris Lapidus and other hotel designers; the first phase of Las Vegas, Nevada; and Southern California, where Richard Neutra built a drive-in church in Garden Grove.

Wildwood, New Jersey

The beachfront resort town of Wildwood, New Jersey, features an array of motel designs, colorfully described by such sub-styles as Vroom, Pu-Pu Platter, Phony Colonee and more.[30][31] The district is known collectively as the Wildwoods Shore Resort Historic District by the State of New Jersey.[7]

The term "doo-wop" was invented by New Jersey's Mid-Atlantic Center for the Arts during the early 1990s to describe the unique, space-age architectural style. Many of Wildwood's Doo-Wop motels were built by Lou Morey, who specialized in such designs.[32] His Ebb Tide Motel, built during 1957 and demolished during 2003, is credited as the first Doo-Wop motel in Wildwood Crest.[33]

Today

After the 1960s, the architectural community rarely appreciated or accepted Googie, considering it too flashy and vernacular for academic praise,[34] and the architecture of the 1970s (especially the International Style) thus abandoned Googie. As Hess discusses, beginning during the 1970s, commercial buildings were meant to blend into the urban environment and not attract attention.[35] Since Googie buildings were part of the service industry, most developers did not think they were worth preserving as cultural artifacts.[36] Despite the humble origins of Googie, Hess writes that, “Googie architecture is an important part of the history of suburbia.”[37] Googie was a symbol of the early days of car culture.

It was not until the 1990s that efforts were made to conserve Googie buildings.[38] However, by this time it was too late to save some famous landmarks such as Googie’s and Ship’s Westwood, which had already been demolished.[39] Despite the loss of these important landmarks, other famous Googie buildings such as Pann's, Norm's, the Wich Stand, and some of the original Bob’s Big Boy locations have been preserved and restored.[40]

In Wildwood, a "Doo Wop Preservation League" works with local business and property owners, city planning and zoning officials, and the state's historic preservation office to help ensure that the remaining historic structures will be preserved. Wildwood's high-rise hotel district has been the first in the USA to enforce "Doo Wop" design guidelines for new construction.[7]

Influence

Googie Architecture developed from the futuristic architecture of Streamline Moderne, extending and reinterpreting technological themes for the new conditions of the 1950s. While 1930s architecture was relatively simple, Googie embraced opulence. Hess argues that the reason for this was that the vision of the future of the 1930s was obsolete by 1950 and thus the architecture evolved along with it. During the 1930s, trains and Lincoln-Zephyrs had been advanced technology, and Streamline Moderne paralleled their smooth simplified aerodynamic exteriors.[41] This simplicity may have represented the depression era’s forced frugality.

Googie heavily influenced retro-futurism. The exaggerated style is appropriately exemplified in the The Jetsons cartoons, and the original Disneyland in Anaheim, California featured a Googie Tomorrowland (much of Tomorrowland still features Googie architecture, such as the Tomorrowland Terrace, Pizza Port, and Disneyland Railroad station). Googie was also the inspiration for the set design style of the Pixar movie The Incredibles and the animated television series Jimmy Neutron and Futurama.

The influence of Googie may also be seen in the early architecture and signage of Las Vegas (c. 1946–1970). This is not coincidental, as many of the same architects who designed Googie coffee shops in Los Angeles also went on to design some of the seminal hotels and casinos in Las Vegas.

The eye-catching style flourished in a carnival atmosphere along multi-lane highways, in motel architecture and above all in commercial signage. Private clients were the main patrons of Googie. Ultimately, the style became unfashionable and, over time, numerous examples of the Googie style have either fallen into disrepair or been destroyed completely.

Gallery

-

Hope International University in Fullerton, California displays classic Googie architecture on its main building (pictured here) and auditorium.

-

Mel's Bowl, a "good example of a mid-century Googie sign" in Redwood City[1]

-

The Anaheim Convention Center, a "big-scale Googie example"[2]

-

Town Motel - Birmingham, Alabama.

-

Abandoned food mart - Woodstock, Tennessee

-

Pedestrian tunnel covers at Aberdeen (MARC station) in Aberdeen, Maryland

-

Kona Lanes (since demolished) in Costa Mesa, California, before (top) and after a remodel that tamed its "ostentatious rooflines"[3]

-

Dot Coffee Shop, Houston, Texas, built 1967[4]

-

Former Skinner Dairy store located in the Lake Shore neighborhood of Jacksonville, Florida.

- ^ Eslinger, Bonnie (2011-09-17). "Mel's Bowl sign in Redwood City is a real 'Googie' and should remain, group says". Palo Alto Daily News. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- ^ Hughes, Holly (2011). Frommer's 500 Places to See Before They Disappear. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 443. ISBN 1-118-16031-2.

- ^ Martelle, Scott (May 27, 2003). "O. C. Bowling Alley's Days Roll to an End". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ Gray, Lisa (August 20, 2014). "Parking peril for the Penguin Arms". Houston Chronicle. (subscription required (help)).

Hardly any of our Googie survives. Besides the Penguin Arms, the marvelous Dot Coffee Shop (at Gulfgate Center) remains a time-warp joy.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Friedlander, Whitney (May 18, 2008). "Go on a SoCal hunt for Googie architecture". Baltimore Sun. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

It was the 1950s. America was a superpower, and the Los Angeles area was a center of it. The space race was on. A car culture was emerging. So were millions of postwar babies. Businesses needed ways to get families out of their automobiles and into coffee shops, bowling alleys, gas stations and motels. They needed bright signs and designs showing that the future was now. They needed color and new ideas. They needed Googie.

- ↑ Stager, Claudette; Carver, Martha (2006). Looking Beyond the Highway: Dixie Roads and Culture. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-57233-467-0. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ Cotter, Bill; Young, Bill (2004). "Populuxe and Pop Art". The 1964-1965 New York World's Fair. Arcadia Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7385-3606-4. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- 1 2 Nelson, Valerie J. (2011-04-26). "Eldon Davis dies at 94; architect designed 'Googie' coffee shops". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

- ↑ John Lautner Why Do Bad Guys Always Get The Best Houses? October 31 by Rory Stott ArchDaily

- ↑ Doo Wop Motels: Architectural Treasures of The Wildwoods by Kirk Hastings 2007, p.2

- 1 2 3 "Doo Wop Preservation League Web site". Doowopusa.org. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- 1 2 Hess 2004, pp. 66–68

- ↑ Hess 2004, pp. 73–74

- ↑ "Googie's". Los Angeles Times. 1986-07-10. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ↑ Langdon 1986, p.114

- ↑ Abbott 1993, p.174

- ↑ "Googie". TIME. 1952-02-25. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

Googie architecture, says HOUSE & HOME, is "Modern Architecture Uninhibited ... an art in which anything and everything goes—so long as it's modern ...

- ↑ Novak, Matt (2012-06-15). "Googie: Architecture of the Space Age". Smithsonian.com. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 26

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 30

- ↑ Hess 2004, pp. 41–42

- 1 2 Hess 2004, p. 29

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 39

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 46–47

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 47 and pp. 192–193

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 50–51

- 1 2 Bob's Big Boy (1970-01-01). "maps.google.com". maps.google.com. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 36

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 86

- ↑ Reyes, Emily Alpert (2015-01-16). "L.A. to consider preservation of Googie-style Norms on La Cienega". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 194

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 192

- 1 2 3 Hess 2004, p. 68

- ↑ "The '50s and '60s Thrive In Retro Doo-Wop Motels". Washington Post. 24 June 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ↑ "WildwoodDooWop.com". WildwoodDooWop.com. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ "History Section". Doowopstuff.com. 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2013-06-25.

- ↑ Wildwood Crest Historical Society Web site

- ↑ Hess 2004, p.66–69

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 178

- ↑ Hess 2004, p.

- ↑ Hess 2004, p.186

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 184

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 181

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 184–185.

- ↑ Hess 2004, p. 46

References

- Abbott, Carl (1993). The Metropolitan Frontier: Cities in the Modern American West. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1129-2.

- Hess, Alan (2004). Googie Redux: Ultramodern Roadside Architecture. Chronicle Books. p. 222. ISBN 978-0811842723. OCLC 249477365. (previously published in 1986 as Googie: Fifties Coffee Shop Architecture ISBN 978-0877013341)

- Langdon, Philip (1986). Orange Roofs, Golden Arches: The Architecture of American Chain Restaurants. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-54401-3.

Further reading

Books are arranged in chronological order by year of publication:

- Learning from Las Vegas, by Robert Venturi 1972 (ISBN 978-0262720069)

- Populuxe: the Look and Life of Midcentury America by Thomas Hine, 1986 (ISBN 978-1585679102)

- LA Lost and Found: An Architectural History of Los Angeles by Sam Hall Kaplan 1987 Pages 145-155

- Southern California in the 50s by Charles Phoenix 2001

- Los Angeles Neon by Nathan Marsak and Nigel Cox 2002

- Mimo: Miami Modern Revealed by Eric P. Nash and Randall C. Robinson, Jr. 2004

- The Leisure Architecture of Wayne McAllister by Chris Nichols, 2007 (ISBN 978-1586856991)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Googie architecture. |

| Look up Googie in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Lotta Living, an online Community for fans of Googie architecture (and the message board for the LAC Modern Committee and Recent Past PReservation Network)

- Googie Architecture Online

- Roadside Peek: Googie Central

- The 1964-1965 New York World's Fair

- Googie architecture at DMOZ

- Synthetrix Photos Of The Forgotten - Documenting Googie style motels surrounding Disneyland in Anaheim, California

- Seattle Googie - Documenting Googie architecture in Seattle, WA

- Wildwood Doo Wop - Documenting "Doo Wop" (Googie) architecture in Wildwood, NJ

- Wildwood, NJ Doo Wop

- Googie style Satellite Hotel in Colorado Springs, Colorado

- Googie definition on Phorio Standards

- Video: "Populuxe in Niagara Falls (feat. Skylon Tower)". YouTube. August 20, 2012.

Preservation groups working to save Googie architecture include

- Los Angeles Conservancy Modern Committee

- Palm Springs Modern Committee

- Doo Wop Preservation League

- Recent Past Preservation Network

- DOCOMOMO, Dutch-founded DOcumentation and COnservation of buildings, sites and neighborhoods of the MOdern MOvement

- Los Angeles Conservancy home

- John Lautner Foundation, Googie architect site