Golgi tendon organ

| Golgi tendon organ | |

|---|---|

Organ of Golgi (neurotendinous spindle) from the human tendo calcaneus. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Organum sensorium tendinis |

| Code | TH H3.03.00.0.00024 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | o_06/12595597 |

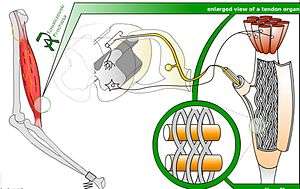

The Golgi organ (also called Golgi tendon organ, GTO, tendon organ, neurotendinous organ or neurotendinous spindle) senses changes in muscle tension. It is a proprioceptive sensory receptor organ that is at the origins and insertion[1] of skeletal muscle fibers into the tendons of skeletal muscle. It provides the sensory component of the Golgi tendon reflex.

The Golgi organ should not be confused with the Golgi apparatus, which is an organelle in the eukaryotic cell, or the Golgi stain, which is a histologic stain for neuron cell bodies. However, all of these structures are named after the Italian physician Camillo Golgi.

Anatomy

The body of the organ is made up of strands of collagen that are connected at one end to the muscle fibers and at the other merge into the tendon proper. Each tendon organ is innervated by a single afferent type Ib sensory nerve fiber that branches and terminates as spiral endings around the collagen strands. The Ib afferent axon is a large diameter, myelinated axon. Each neurotendinous spindle is enclosed in a fibrous capsule which contains a number of enlarged tendon fasciculi (intrafusal fasciculi). One or more nerve fibres perforate the side of the capsule and lose their medullary sheaths; the axis-cylinders subdivide and end between the tendon fibers in irregular disks or varicosities (see figure).

Function

When the muscle generates force, the sensory terminals are compressed. This stretching deforms the terminals of the Ib afferent axon, opening stretch-sensitive cation channels. As a result, the Ib axon is depolarized and fires nerve impulses that are propagated to the spinal cord. The action potential frequency signals the force being developed by 10 to 20 of the many motor units within the muscle. This is representative of whole muscle force.[2]

The Ib sensory feedback generates spinal reflexes and supraspinal responses which control muscle contraction. Ib afferents synapse with interneurons that are within the spinal cord that also project to the brain cerebellum and cerebral cortex. The autogenic inhibition reflex assists in regulating muscle contraction force. It is associated with the Ib. Tendon organs signal muscle force through the entire physiological range, not only at high strain.[2][3]

During locomotion, Ib input excites rather than inhibits motoneurons of the receptor-bearing muscles, and it affects the timing of the transitions between the stance and swing phases of locomotion.[4] The switch to autogenic excitation is a form of positive feedback.[5]

The ascending or afferent pathways to the cerebellum are the dorsal and ventral spinocerebellar tracts. They are involved in the cerebellar regulation of movement.

History

Until 1967 it was believed that Golgi tendon organs had a high threshold, only becoming active at high muscle forces. Consequently it was thought that tendon organ input caused "weightlifting failure" through the clasp-knife reflex, which protected the muscle and tendons from excessive force. However, the underlying premise was shown to be incorrect by James Houk and Elwood Henneman in 1967.<ref name="Houk" ">Houk, J.; Henneman, E. (1967). "Responses of Golgi tendon organs to active contractions of the soleus muscle of the cat". J Neurophysiology 30 (3): 466–481. PMID 6037588.</ref>

See also

Sources

- ↑ Moore JC: The Goigi Tendon Organ: A Review and Update; American Journal of Occupational Therapy, April 1984 vol. 38 no. 4 227-236

- 1 2 Prochazka, A.; Gorassini, M. (1998). "Ensemble firing of muscle afferents recorded during normal locomotion in cats". J Physiology 507 (1): 293–304. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.293bu.x. PMC 2230769. PMID 9490855.

- ↑ Stephens, J. A.; Reinking, R. M.; Stuart, D. G. (1975). "Tendon organs of cat medial gastrocnemius: responses to active and passive forces as a function of muscle length". J Neurophysiology 38 (5): 1217–1231. PMID 1177014.

- ↑ Conway, B. A.; Hultborn, H.; Kiehn, O. (1987). "Proprioceptive input resets central locomotor rhythm in the spinal cat". Experimental Brain Research 68 (3): 643–656. doi:10.1007/BF00249807. PMID 3691733.

- ↑ Prochazka, A.; Gillard, D.; Bennett, D. J. (1997). "Positive Force Feedback Control of Muscles". J Neurophysiol 77 (6): 3226–3236. PMID 9212270.

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

External links

- http://ami.usc.edu/projects/ami/projects/bion/musculoskeletal/golgi_tendon_organ.html

- http://www.lib.mcg.edu/edu/eshuphysio/program/section8/8ch3/s8ch3_11.htm

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||