Kingdom of Cochin

| Kingdom of Cochin | |||||

| കൊച്ചി പെരുമ്പടപ്പ് സ്വരൂപം | |||||

| Princely state of the British Indian Empire | |||||

| |||||

| Anthem "Om Namo Narayana" | |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Mahodayapuram (Thiruvanchikulam) Vanneri Cochin Thripunithura Thrissur | ||||

| Languages | Malayalam, English | ||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy Princely state (1814–1947) | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | circa 12th century | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1947 | |||

| Currency | Rupee and Other Local Currencies | ||||

| Today part of | Kerala, India | ||||

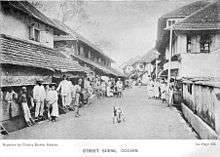

Kingdom of Cochin (also known as Perumpadappu Swaroopam, Mada-rajyam, Gosree Rajyam, or Kuru Swaroopam; Malayalam: കൊച്ചി Kocci or പെരുമ്പടപ്പ് Perumpaṭappu) was a late medieval Hindu kingdom and later Princely State on the Malabar Coast, South India. Once controlling much of the territory between Ponnani and Kochi in Malabar, the Cochin kingdom shrank to its minimal extent as a result of invasions by the Zamorin of Calicut. When Portuguese armadas arrived in India, Cochin was in vassalage to Zamorin and was looking for an opportunity to break away. King Unni Goda Varma Tirumulpadu (Trimumpara Raja) warmly welcomed Pedro Álvares Cabral on 24 December 1500 and negotiated a treaty of alliance between Portugal and the Cochin kingdom, directed against the Zamorin of Calicut. Cochin became a long-time Portuguese protectorate (1503–1663) providing assistance against native overlords. After the Portuguese, the Dutch East India Company (1663–1795) followed by the English East India Company (1795–1858, confirmed on 6 May 1809), protected the Cochin state.

The Kingdom of Cochin, originally known as Perumpadappu Swarupam, was under the rule of the Later Cheras in the Middle Ages. The Brahmin chief of Perumpadappu (Chitrakuda, Vannerinadu, Ponnani taluk) had married the sister of the last Later Chera king, Rama Varma Kulashekhara, and as a consequence obtained Mahodayapuram, and Thiruvanchikkulam Temple along with numerous other rights, such as that of the Mamankam festival. After the fall of the Mahodayapuram Cheras in the 12th century, along with numerous other provinces Perumpadappu Swarupam became a free political entity. However, it was only after the arrival of Portuguese colonizers on the Malabar Coast did the Perumpadappu Swarupam acquire any political importance. Perumpadappu rulers had family relationships with the Nambudiri rulers of Idappally. After the transfer of Kochi and Vypin from Idappally rulers to the Perumpadappu rulers, the latter came to be known as kings of Kochi. Ma Huan, the Muslim voyager and translator who accompanied Admiral Zheng He on three of his seven expeditions to the Western Oceans, describes the king of Cochin as being a Buddhist.

Territories

The Cochin kingdom (the Princely State) included much of modern-day Thrissur district, Alathur & Chittoor Taluks of the Palakkad district and Kochi Taluk, most of Kanayannur Taluk (excluding Edappally), parts of Aluva Taluk (Chovvara, Kanjoor, Srimoolanagaram) and parts of Paravur Taluk (Chendamangalam) of the Ernakulam district which are now the part of the Indian state of Kerala.

History

Origin

There is no extant written evidence about the emergence of the Kingdom of Cochin or of the Cochin Royal Family, also known as Perumpadapu Swaroopam.[1] All that is recorded are folk tales and stories, and a somewhat blurred historical picture about the origins of the ruling dynasty.

The surviving manuscripts, such as Keralolpathi, Keralamahatmyam, and Perumpadapu Grandavari, are collections of myths and legends that are less than reliable as conventional historical sources. There is an oft-recited legend that the last Perumal (king from the Chera dynasty) who ruled the Chera dynasty divided his kingdom between his nephews and his sons, converted to Islam and traveled to Mecca on a hajj. The Keralolpathi recounts the above narrative in the following fashion:

The last and the famous "Perumal" ruled Kerala for 36 years. He left for Mecca by ship with some Muslims who arrived at Kodungallur (Cranganore) port and converted to Islam. Before leaving for Mecca, he divided his kingdom between his nephews and sons.

The Perumpadapu Grandavari contains an additional account of the dynastic origins:

The last Thavazhi of Perumpadapu Swaroopam came into existence on the Kaliyuga day shodashangamsurajyam. Cheraman Perumal divided the land in half, 17 "amsa" north of Neelaeswaram and 17 amsa south, totaling 34 amsa, and gave his powers to his nephews and sons. Thirty-four kingdoms between Kanyakumari and Gokarna (now in Karnataka) were given to the "thampuran" who was the daughter of the last niece of Cheraman Perumal.

Keralolpathi recorded the division of his kingdom in 345 AD, Perumpadapu Grandavari in 385 AD, William Logan in 825 AD. There are no written records on these earlier divisions of Kerala, but according to some historians the division might have occurred during the Second Chera Kingdom at the beginning of the 12th century.[2]

Historians, including Robin Jeffry, Faucett and Samuel Mateer, are of the opinion that as with all other Kings of Malabar (Kerala), the Cochin Raja (Perumpadapum Moopil) was also of Nair origin. Mateer states: "There seems reason to believe that the whole of the kings of Malabar also, notwithstanding the pretensions set up for them of late by their dependents, belong to the same great body, and are homogeneous with the mass of the people called Nairs."[3][4]

Before the Portuguese arrival

Cochin kingdom ruled over a vast area in central Kerala before the Portuguese arrival. Their state stretched up to Ponnani and Pukkaitha in the north, Anamalais in the east, and Cochin and Porakkad in the south, with capital at Perumpadappu on the northern border. Later, Calicut conquered large parts of Perumpadappu Kingdom, and made them a tributary state.

Portuguese period (1503–1663)

Cochin was the scene of the first European settlement in India. In the year 1500, the Portuguese Admiral Pedro Álvares Cabral landed at Cochin after being repelled from Calicut. The king of Cochin welcomed the Portuguese and a treaty of friendship was signed. Promising his support in the conquest of Calicut, the admiral coaxed the king into allowing them to build a factory at Cochin (and upon Cabral's departure Cochin allowed thirty Portuguese and four Franciscan friars to stay in the kingdom). Assured by the offer of support, the king declared "war" on their superior masters, the Zamorins of Calicut.

In 1502 a new expedition under the command of Vasco da Gama arrived at Cochin, and the friendship was renewed. Vasco da Gama later bombed Calicut and destroyed the Arab factories there. This enraged the Zamorin, the ruler of Calicut, and he attacked Cochin after the departure of Vasco da Gama and destroyed the Portuguese factory. The king of Cochin and his Portuguese allies were forced to withdraw to Vypin Island. However, the arrival of a small reinforcement Portuguese fleet and, some days later by Duarte Pacheco Pereira and the oncoming monsoons alarmed the Zamorin. Calicut recalled the army and immediately abandoned the siege. The Zamorin also retreated because of the revered local festival of Onam which the Zamorin intended to keep the auspicious day holy. However, much of Cochin had been burnt and destroyed by the Zamorin.

After securing the throne for the king of Cochin, the Portuguese got permission to build a fort – Fort Emmanuel (at Fort Kochi, named after the king of Portugal) – surrounding the Portuguese factory, in order to protect it from any further attacks from Calicut and on 27 September 1503 the foundations of a timber fort, the first fort erected by the Portuguese in India, were laid. The entire work of construction was commissioned by the ruler of Cochin, who supplied workers and material. In 1505, the stone fortress replaced the wooden fort. Later, for a better defence of the town, a fort called "Castelo de Cima" was built on Vypeen Island at Paliport. At the departure of the Portuguese fleet, only Duarte Pacheco Pereira and a small feet were left in Cochin. Meanwhile, the Zamorin of Calicut formed a massive force and attacked them. For five months, Pacheco Pereira and his men were able to sustain and drive back Calicut's assaults.

The ruler of Cochin continued to rule with the help of the Portuguese. Meanwhile, the Portuguese secretly tried to enter into an alliance with the Zamorin. A few later attempts by the Zamorin to conquer the Cochin port were thwarted by the ruler of Cochin with the help of the Portuguese. Slowly, the Portuguese armory at Cochin was increased, presumably to help the king protect Cochin. However, the measured led to a reduction of the power of the king and an increase in Portuguese influence. From 1503 to 1663, Cochin was virtually ruled by Portugal through the namesake Cochin raja. Cochin remained the capital of Portuguese India until 1530. And for a long a time, right after Goa, Cochin situated in the center of East Indies, was the best place Portugal had in India. From there the Portuguese exported large volumes of spices, particularly pepper.

In 1530, Saint Francis Xavier arrived and founded a Latin Christian mission. Cochin hosted the grave of Vasco da Gama, the Portuguese viceroy, who was buried at St. Francis Church until his remains were returned to Portugal in 1539.[5] Soon after the time of Afonso de Albuquerque, Portuguese rule in Kerala declined. The failure is attributed to several factors like intermarriages, forcible conversions, religious persecution, etc.

Dutch period (1663–1773)

Portuguese rule was followed by that of the Dutch, who had by then conquered Quilon after various encounters with the Portuguese and their allies. Discontented members of the Cochin Royal family called on the assistance of the Dutch for help in overthrowing the Cochin Raja. The Dutch successfully landed at Njarakal and went on to capture the fort at Pallippuram, which they handed over to the Zamorin.

Mysorean invasion

The 1773 conquest of the Mysore by Hyder Ali in the Malabar region descended to Kochi. The Kochi Raja had to pay a subsidy of one hundred thousand of Ikkeri Pagodas (equalling 400,000 modern rupees). Later on, in 1776, Haider captured Trichur, which was under the Kingdom of Kochi. Thus, the Raja was forced to become a tributary of Mysore and to pay a nuzzar of 100,000 of pagodas and 4 elephants and annual tribute of 30,000 pagodas. The hereditary prime ministership of Cochin came to an end during this period.

British period (1814–1947)

In 1814 according to the Anglo-Dutch Treaty, the islands of Kochi, including Fort Kochi and its territory, were ceded to the United Kingdom in exchange for the island of Banca. Even prior to the signing of the treaty, there is evidence of English residents in Kochi.[6] Towards the early 20th century, trade at the port had increased substantially and the need to develop the port was greatly felt. The harbour engineer Robert Bristow was thus brought to Cochin in 1920 under the direction of Lord Willingdon, then Governor of Madras. Over a span of 21 years he transformed Cochin into the safest harbour in the peninsula, where ships berthed alongside the newly reclaimed inner harbour, which was equipped with a long array of steam cranes.[7] Meanwhile, in 1866, Fort Cochin was made a municipality, and its first Municipal Council election with a board of 18 members was conducted in 1883. The Maharajah of Cochin initiated local administration in 1896 by forming town councils in Mattancherry and Ernakulam. In 1925, a Kochi legislative assembly was constituted due to public pressure on the state. The assembly consisted of 45 members, 10 were officially nominated. Thottakkattu Madhaviamma was the first woman to be a member of any legislature in India.[8] Kochi was the first princely state to willingly join the Indian Union when India gained independence in 1947. Cochin merged with Travancore to create Travancore-Cochin, which was in turn merged with the Malabar district of Madras State on 1 November 1956 to form the new Indian state of Kerala.[9]

Administration

For administrative purposes, Cochin was divided into seven taluks:- Chittur, Cochin, Cranganore, Kanayannur, Mukundapuram, Trichur and Talapilly.

| Taluk | Area (in square miles) | Headquarters |

|---|---|---|

| Chittur | 285 | Chittur |

| Cochin | 63 | Mattancherry |

| Cranganore | 19 | Cranganore |

| Kanayannur | 81 | Ernakulam |

| Mukundapuram | 418 | Irinjalakuda |

| Talapalli | 271 | Vadakkancheri |

| Trichur | 225 | Trichur |

| Total | 1,362 |

Capitals

The capital of Perumpadapu Swaroopam was located at Chitrakooda in the Perumpadapu village of Vanneri from the beginning of the 12th century to the end of the 13th century. Even though the capital of Perumpadapu Swaroopam was in Vanneri, the Perumpadapu king had a palace in Mahodayapuram.

When the Zamorins attacked Vanneri in the later part of the 13th century, Perumpadapu Swaroopam shifted their capital from Vanneri to Mahodayapuram. In 1405 Perumpadapu Swaroopam changed their capital from Mahodayapuram to Cochin. By the end of the 14th century the Zamorin conquered Thrikkanamathilakam and it became a threat for Mahodayapuram (Thiruvanchikulam), which may be the reason that Perumpadapu Swaroopam changed their capital to Cochin from Mahodayapuram. Moreover, in the year 1341 a flood created an island, Puthuvippu (Vypin), and Cochin became a noted natural harbor for the Indian Ocean trade.[10] The old Kodungallore (Cranganore) port lost its importance, which may also be a cause for the shift of the capital. From there on Perumpadapu Swaroopam used the name Cochin Royal Family.

Finally, the arrival of the Portuguese on the Indian subcontinent in the sixteenth century likely influenced Cochin politics. The Kingdom of Cochin was among the first Indian nations to sign a formal treaty with a European power, negotiating trade terms with Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500.

The palace at Kalvathhi was originally the residence of the kings. In 1555, though, the royal palace moved to Mattancherry,[11] and later relocated to (Thrissur). At that time Penvazithampuran (Female Thampuran) and the other Kochuthampurans (other Thampurans except the Valliathampuran (King)) stayed at a palace in Vellarapilly.

In the beginning of 18th century Thripunithura started gaining prominence. The kingdom was ruled from Thrissur, Cochin and Thripunithura.[12] Around 1755 Penvazithampuran (Female Thampuran) and the other Kochuthampurans (other Thampurans) left Vellarapalli and started to live in Thripunithura. Thus Thripunithura became the capital of the Cochin Royal Family.

Alternative names of the kingdom

Perumpadapu Swaroopam, Madarajyam, Goshree Rajyam, and Kuru Swaroopam are among the different names ascribed to the Cochin Kingdom. Perumpadapu Velliya Thampuran, Madamaheeshan, Goshree Bhoopan, Kuru Bhoomi Bhrith are different names for the kings.

According to the wishes of Vishravanan's daughter, Lord Parashurama purportedly retrieved a small piece of land for her called Balapuri, which translates as "small land" (Kochu Desham) in Malayalam. This region was later called Kochi (Cochin). According to Nichola County (15th century) and Fr. Paulino da San Bartolomeo (17th century), Kochi was given up after a stream flowed through the place. This may be correct, since the capital of the kingdom was Kochi, and the entire kingdom was known by the name Kochi.

The Thruvanjikulam Temple structure is built in keeping with the Chidambaram architectural form. The temple's founder might have been a Chola Perumal from Chidambaram; there is a tiger inscribed on the flag, called Puliyan, and his realm became known as Pulyannur. This was detailed in the notes of historian Putheyadath Raman Menon. Since Puliyannur Namboothiri (Tantri Poornathrayeesa Temple and Cochin Royal Family) originated from this place that Illom got this name. Some scholars suggest that the name Perumpadapu came from Perumbathura Periyavar (an elder of Perumbathura, a village near Chidambaram), but this theory lacks evidentiary support.

There was an adoption of Madathinkizu (Madathum Koor) Swoorupam from the Perumpadapu Swaroopam, and there was no predecessor in Madathinkizu; these properties were attached to Perumpadapu Swaroopam. Thus the name Madarajyam came into existence. The Sanskrit version of Madavamsham is Goshree Vamsham (Madu (Malayalam)= Pashu (Malayalam)= Go (Sanskrit)). Kochi is a synonym for Goshree. There was also an adoption from Cochin Royal Family to Kuru Swaroopam and finally Kuru Swaroopam was merged with Kochi, hence the name Kuru Swaroopam.

Maharajas of Cochin

Veerakerala Varma, nephew of Cheraman Perumal, is the person traditionally believed to be the first Maharaja of Cochin. The written records of the dynasty, however, date from 1503 CE. The Maharaja of Cochin was also called Gangadhara Kovil Adhikaarikal, meaning Head of all Temples.[13]

As Portuguese and Dutch protectorate states

.jpg)

- Unniraman Koyikal I (c. 1500 to 1503)

- Unniraman Koyikal II (1503 to 1537)

- Veera Kerala Varma I (1537–1565)

- Keshava Rama Varma (1565–1601)

- Veera Kerala Varma II (1601–1615)

- Ravi Varma I (1615–1624)

- Veera Kerala Varma III (1624–1637)

- Goda Varma I (1637–1645)

- Veerarayira Varma (1645–1646)

- Veera Kerala Varma IV (1646–1650)

- Rama Varma I (1650–1656)

- Rani Gangadharalakshmi (1656–1658)

- Rama Varma II (1658–1662)

- Goda Varma II (1662–1663)

- Veera Kerala Varma V (1663–1687)

- Rama Varma III (1687–1693)

- Ravi Varma II (1693–1697)

- Rama Varma IV (1697–1701)

- Rama Varma V (1701–1721)

- Ravi Varma III (1721–1731)

- Rama Varma VI (1731–1746)

- Kerala Varma I (1746–1749)

- Rama Varma VII (1749–1760)

- Kerala Varma II (1760–1775)

- Rama Varma VIII (1775–1790)

- Rama Varma IX (Shaktan Thampuran) (1790–1805)

As British protectorate state

- Rama Varma IX (Shaktan Thampuran) (1790–1805)

- Rama Varma X (1805–1809) – Vellarapalli-yil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Vellarapali")

- Kerala Varma III (Veera Kerala Varma) (1809–1828) – Karkidaka Maasathil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "karkidaka" month(ME))

- Rama Varma XI (1828–1837) – Thulam-Maasathil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Thulam" month (ME))

- Rama Varma XII (1837–1844) – Edava-Maasathil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Edavam" month (ME))

- Rama Varma XIII (1844–1851) – Thrishur-il Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Thrishivaperoor" or Thrishur)

- Kerala Varma IV (Veera Kerala Varma) (1851–1853) – Kashi-yil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Kashi" or Varanasi)

- Ravi Varma IV (1853–1864) – Makara Maasathil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Makaram" month (ME))

Under the Crown

- Ravi Varma IV (1853–1864) – Makara Maasathil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Makaram" month (ME))

- Rama Varma XIV (1864–1888) – Mithuna Maasathil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Mithunam" month (ME))

- Kerala Varma V (1888–1895) – Chingam Maasathil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Chingam" month (ME))

- Rama Varma XV (Sir Sri Rama Varma) (1895–1914) – aka Rajarshi, Abdicated Highness (died in 1932)

- Rama Varma XVI (1914–1932) – Madrasil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in Madras or Chennai)

- Rama Varma XVII (1932–1941) – Dhaarmika Chakravarthi (King of Dharma), Chowara-yil Theepetta Thampuran (King who died in "Chowara")

- Kerala Varma VI (1941–1943) – Midukkan Thampuran

- Ravi Varma V (Ravi Varma Kunjappan Thampuran) (1943–1946) – Kunjappan Thampuran (Brother of Midukkan Thampuran)

- Kerala Varma VII (1946–1947) – Aikya Keralam Thampuran (The King who unified Kerala)

Post Independence

- Rama Varma XVIII (1948-1964) He was known by the name of Parikshith Thampuran. He was the last official ruler of Cochin Empire

- Rama Varma XIX (1964-1975)– Lalan Thampuran

- Rama Varma XX (1975-2004) – Anyian Kochunni Thampuran

- Kerala Varma VIII (2004-2011) – Kochunni Thampuran

- Rama Varma XXI (2011-2014) – Kochaniyan Thampuran

- Ravi Varma VI (2014-) - Kochaniyan Thampuran

ME – Malayalam Era

Chiefs of Cochin

The Paliath Achan, or head of the Paliam Nair family of Chendamangalam, played an important part in the politics of Cochin State since the early seventeenth century, and held hereditary rights to the ministership of Cochin. The Paliath Achan was the most powerful person after the king, and he sometimes exerted more power than the king.

In addition, there were many Desaavzhis around the Cochin area, among them Paliyam swaroopam, who was second to the Perumpadappu swaroopam. Other powerful lords around these areas were "Cheranellore Karthavu" who was the head of the Anchi Kaimals","Muriyanatt(Mukundapuram) Nambiar" who was the head of Arunattil Prabhus,"Kodassery Kartha"" "Mappranam Prabhu"-"Vellose Nair","Chengazhi Nambiar(Chengazhinad Naduvazhi)", "Edappali Nampiyathiri,"

KP Padmanabha Menon in his History of Kerala, Vol 2 mentions the Anji Kaimals whose Chief was the Cheranellur Kartha as owning all of Eranakulam. In fact, Eranakulam is known as Anji Kaimal in the early maps of Kerala. See Dutch in Malabar (Dutch Records No 13), 1910 shows a map from AD1740 that shows the area of AnjiKaimal as almost twice as large as the Cochin State. The other Chiefs he mentions quoting Gollennesse (Dutch East India Company) is the 1) Moorianatt Nambiar 2) Paliath Achan (mentioned above), 3)Codacherry (Kotasseri) Kaimal, 4) Caimalieone (female Kaimal) of Corretty, 5) Changera Codda Kaimal, and 6) Panamoocattu Kaimal (Panambakadu Kaimal). The last four Kaimals are known as the Kaimals of Nandietter Naddu. The Kaimals of Nandietter Naddu had Nayar troops of 43,000 according to Heer Van Reede of the Dutch East India Company from 1694. (Page 241 and 242)

" "Shakthan Thampuran" destroyed their powers and confisicated the properties of most of these lords. However, following the rebellion of the Paliath Achan along with Velu Thampi Dalawa in 1810, the powers of this chief were curbed.

Matrilineal Inheritance

Cochin Royal Family followed the system of Matrilineal succession known as Marumakkatayam Traditionally the female members of the family have hypergamous unions (Sambandham) with Namboodiri Brahmins while male members marry ladies of the Samanthan Nair class. These wives of the male members are not Ranis as per the matrilineal system but instead get the title of Nethyar Amma.Currently the family marries mostly within the Malayala Kshatriya class[14]

Traditional Rituals

The term "Shodasakriyakal" refers to sixteen rites to be performed by all members, as structured through "Smruthi".

- Sekom (Garbhaadhaanam) : A rite to be performed just before the first sexual intercourse after marriage.

- Pumsavanom : To be performed just after conception.

- Seemantham : Performed after Pumsavanom.

- Jathakarmam : Performed just after birth.

- Naamakaranam : Naming Ceremony of the child.

- (Upa)nishkramanam (Vaathilpurappadu) : Involves taking the child out of the house for the first time.

- Choroonu : The first ceremonial intake of rice by the child.

- Choulam : The first hair-cut ceremony of the boy/ girl.

- Upanayanam : (Only for boys).

- Mahaanamneevrutham (Aanduvrutham) :

- Mahaavrutham :

- Upanishadvrutham :

- Godaanam : Rites as part of thanks-giving to the Aacharyan (priest or teacher).

- Samaavarthanam : A long ritual for the completion of the above said Vedic education.

- Marriage

- Agniadhaanam : A rite performed as an extension of Oupaasanam and introduction to Sroutha rites.

Deities

- Paradevatha (goddess): Vannery Chitrakoodam, Pazhayannur Bhagavathy, Chazhur Pazhayannur Bhagavathy

- Paradevan (god): Vishnu (Sree Poornathrayeesa), Tiruvanchikulathappan (Lord Shiva of Thiruvanchikulam between North Paravur and Kodungallore)

- Other Deities: Chottanikkara Bhagavathy, Pulpalli Thevar and many more

Naming practice of male Thampuran

In Cochin royal family all the male Thampurans were named according to the following methodology.

- Eldest son to a mother Goda Varma (no longer used)

- Second Son Rama Varma

- Third Son Kerala Varma

- Fourth Son Ravi Varma.

From then on to till date the last three naming convention is followed. But the name Goda varma is followed in the other root family (moola thavazhi) of cochin royal family namely Chazhur kovilakam. Reference – Genealogy of Cochin Royal Family

Naming practice of female Thampuran

In Cochin Royal Family the female Thampurans were named according to the following methodology.

- Eldest daughter to a Mother – Ammba

- Second daughter – Ambika

- Third Daughter – Ambalika

This naming convention is followed again to third daughter and fourth etc.

Both the female and male members are called by the name "Thampuran" and have same last name(Thampuran). (in all other royal families in Kerala, males are called Thampuran and females – Thampuratti. For more details, please visit )

Parukutty Nethyar Amma

Maharaja Rama Varma (popularly known as Madrassil Theepetta Thampuran), who reigned from 1914 to 1932, was assisted by a particularly able consort named Parukutty Nethyar Amma (b. 1874).[15] The Nethyar was the daughter of Kurur Namboodiripad, who was a member of the family that had the traditional honour of anointing the kings of Palakkad. Her mother belonged to the Padinjare Shrambhi house of the aristocratic Vadakke Kuruppath house of Trichur. She married the Maharaja, then fourth in line to the succession, when she was fourteen years old in 1888. It is said that she was especially blessed by the Devi at the Chottanikkara Temple. By a quirk of fate her husband ascended the throne as a result of the abdication of his predecessor. Since the Maharaja was a scholar and had other interests (including knowledge of how to cure snake bites and comprehend the language of lizards known as Gawli Shashtra), she took over the finances of the state. Under her guidance salaries were quadrupled and the increased revenue earned her a 17-gun salute. Parukutty Nethyar Amma was awarded the Kaiser-i-Hind Medal by King George V in 1919 for public work and came to be known as Lady Rama Varma of Cochin.[16]

The Nethyar Amma was not only an able administrator but also a Nationalist, moving from being seen as an exemplary public figure in the eyes of the British to earning the ire of the colonial state for her relationships with Mahatma Gandhi and Indian nationalists. As one British intelligence report stated, "The hill palace is the centre of nationalist activity and charkhas have been introduced to assist the weaving of khadi." (see Fortnightly Intelligence Reports available at the National Archives of India) In addition, a little known fact about the Cochin state is the attempt made by the British government and the Viceroy to force the Maharajah to abdicate under the ploy of trying to prove him insane. A doctor was brought from London to bolster the case, and the physician opined that the "Maharaja was merely an old man who tired easily". This attempt was directly linked to the fear that the Nethyar Amma, or the "Consort" as she was referred to by the British, was becoming increasingly powerful in nationalist circles.[15]

The head of the Congress party in Cochin was Kurur Nilakantan Namboodiripad who was a cousin of the Nethyar Amma. The Collected Works containing Gandhi's letters include correspondence between the Maharajah's daughter V. K. Vilasini Amma and himself, and a second daughter V.K Ratnamma was married to R. M. Palat, himself a politician and the son of Sir C. Sankaran Nair, the former president of the Congress Party and well known nationalist.[15] The Maharaja's eldest son V. K. Raman Menon studied in Oxford, married to Tiruthipalli Payathil Madhavi and had one son by name V. K. T. Raman Menon. The Maharaja's second son V.K Aravindaksha Menon was married to Malathy, the daughter of V. K Narayana Menon a prominent contractor in Trichur in whose house "Pandyala", Jawaharlal Nehru, Kamala and Indira Nehru rested on their way to Sri Lanka. When Gandhi visited Cochin, he was treated as a state guest, and Aravindaksha Menon, the Nethyar Amma's son personally was deputed to accompany him. Soon Parukutty Nethyar Amma appeared opposedo, which proved to be a significant hurdle for British interests in India.[15]

On the death of the Maharaja, the Nethyar Amma initially retired to the palace she had constructed for herself in her home town Trichur, near her ancestral house, Padinjare Shrambhi. The house, Ratna Vilas, was named after her elder daughter Ratnam. The Nethyar Amma then went on an extended tour abroad, taking along her grandson Sankaran Palat, who was admitted to Le Rosey in Switzerland and later to Charterhouse, England. She returned to India and divided her time between Trissur and Coonoor, where she purchased two tea estates and a tea factory.

The dynasty today

Members of the dynasty are spread all over the world (In five continents). The family is one of the world's largest royal families, numbering more than 1000 people, and many members of the family still live in and around Thrissur (Chazhur), Tripunithura and other parts of Kochi.[17]

Gallery

-

Chazhoor village holds the ancient palace of Chazhoor (Chazur) kovilakom. This is the root (moola thavazhi)of the Cochin royal family, in Ernakulam district (Perumpadappu swaroopam).

-

Vadakke kettu (nalukettu in the north side of the Palace)

-

The Naalukettu (Kerala style of joint family house) of Chazhoor royal family is in this village.

-

Nalukettu

-

Late.Shri KeralaVarma Appukuttan Thampuran(1943-2012)a member of Chazhur Kovilakam

-

Chazhur Kovilakam Vadakkekettu - Maalika

See also

- History of Cochin Royal Family

- Cochin Royal Family

- Political integration of India

- History of Kochi

- Thrippunithura Royal Heritage

References

- ↑ Kerala.com (2007). "Kerala History". Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ Pillai, Elamkulam Kunjan (1970). Studies in Kerala History.

- ↑ Samuel Mateer (1883), Native Life of Travancore

- ↑ Robin Jeffary, The Decline of Nair Dominance

- ↑ "Death of Vasco Da Gama in Kochi". MSN Encarta Encyclopedia. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2006.

- ↑ Kochi Rajyacharithram by KP Padmanabha Menon. P(1914)

- ↑ "The Cochin Saga". Robert Charles Bristow employed to develop Kochi port. Corporation of Kochi. Retrieved 23 May 2006.

- ↑ "History and culture of Kochi". Corporation of Kochi. Retrieved 23 May 2006.

- ↑ PBS (2007). "Hidden India:The Kerala Spicelands". Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ "History of Cochin – Ernakulam". 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ "Kochi – Queen of the Arabian Sea". KnowIndia.netdate=2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ "Cochin Royal Family History – Post-1715". 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ Thampuran, Rameshan (2007). "Emergence Of Kingdom of Cochin and Cochin Royal Family". Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ Staff Correspondent (3 March 2003). "Seeking royal roots". The Hindu. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Cochin Royal Family History – Post-1715". 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ The National Archives | A2A | Results

- ↑ "Seeking royal roots". The Hindu. India. 2003. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kingdom of Cochin. |

Further reading

- Genealogy of Cochin Royal Family – By Rameshan Thampuran

Bibliography

- Katz, Nathan and Goldberg, Helen S. Kashrut, Caste and Kabbalah: The Religious Life of the Jews of Cochin. Mahonar Books, 2005.

- Kulke, Herman. A History of India. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Menon, P. Shungoonny. History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. 1878.

- Pillai, Elamkulam Kunjan. Studies in Kerala History. Kottayam, 1970.

- Ramachandran, Rathi. History of Medieval Kerala. Pragati Publications, 2005.

- Thampuran, Rameshan. Genealogy of Cochin Royal Family.

- History of Kerala, KP Padmanabha Menon, Vol. 2.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||