Glow stick

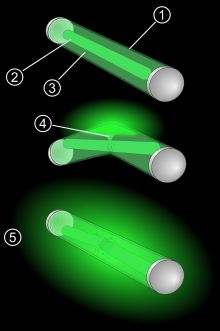

2. A glass capsule covers the solution.

3. Phenyl oxalate and fluorescent dye solution

4. Hydrogen peroxide solution

5. After the glass capsule is broken and the solutions mix, the glowstick glows.

A glow stick is a self-contained, short-term light-source. It consists of a translucent plastic tube containing isolated substances that, when combined, make light through chemiluminescence, so it does not require an external energy source. The light cannot be turned off, and can be used only once. Glow sticks are often used for recreation, but may also be relied upon for light during military, police, fire, or EMS operations.

History

Bis(2,4,5-trichlorophenyl-6-carbopentoxyphenyl)oxalate, trademarked "Cyalume", was invented by Michael M. Rauhut[1] and Laszlo J. Bollyky of American Cyanamid, based on work by Edwin A. Chandross of Bell Labs.[2][3] Other early work on chemiluminescence was carried out at the same time, by researchers under Herbert Richter at China Lake Naval Weapons Center.[4][5]

Several US patents for "glow stick" type devices were received by various inventors. Most of these are assigned to the US Navy. The earliest patent lists Bernard Dubrow and Eugene Daniel Guth as having invented a Packaged Chemiluminescent Material in June 1965 (Patent 3,774,022). In October 1973, Clarence W. Gilliam, David Iba Sr., and Thomas N. Hall were registered as inventors of the Chemical Lighting Device (Patent 3,764,796). In June, 1974 a patent for a Chemiluminescent Device was issued with Herbert P. Richter and Ruth E. Tedrick listed as the inventors (Patent 3,819,925).

In January 1976, a patent was issued for the Chemiluminescent Signal Device, with Vincent J. Esposito, Steven M. Little, and John H. Lyons listed as the inventors (Patent 3,933,118). This patent recommended a single glass ampoule that is suspended in a second substance, that when broken and mixed together, provide the chemiluminescent light. The design also included a stand for the signal device so it could be thrown from a moving vehicle and remain standing in an upright position on the road. The idea was this would replace traditional emergency roadside flares and would be superior, since it was not a fire hazard, would be easier and safer to deploy, and would not be made ineffective if struck by passing vehicles. This design, with its single glass ampoule inside a plastic tube filled with a second substance that when bent breaks the glass and then is shaken to mix the substances, most closely resembles the typical glow stick sold today.

In December 1977 a patent was issued for a Chemical Light Device with Richard Taylor Van Zandt as the inventor (Patent 4,064,428). This design alteration features a steel ball that shatters the glass ampoule when the glow stick is exposed to a predetermined level of shock; an example of its use being that an arrow can be flown dark but illuminate its landing location upon sudden deceleration.

Uses

Practical Applications

Glow sticks are used for many purposes. They are waterproof, do not use batteries, generate negligible heat, are inexpensive, and are reasonably disposable. They can tolerate high pressures, such as those found under water. They are used as light sources and light markers by military forces, campers, and recreational divers.[6] Glow sticks are considered the only light source that is safe for use immediately following any catastrophic event.

Entertainment

Glowsticking is the use of glow sticks in dancing.[7] This is one of their most widely known uses in popular culture, as they are frequently used for entertainment at parties (in particular raves), concerts, and dance clubs. They are used by marching band conductors for evening performances; glow sticks are also used in festivals and celebrations around the world. Glow sticks also serve multiple functions as toys, readily visible night-time warnings to motorists, and luminous markings that enable parents to keep track of their children. Yet another use is for balloon-carried light effects. Glow sticks are also used to create special effects in low light photography and film.[8]

The Guinness Book of Records says the world's largest glow stick, 8 ft 4 in (2.54 m) tall, was built and illuminated at the opening ceremony of the second Bang Face Weekender at a holiday park in Camber Sands, East Sussex, England, on April 24, 2009.[9]

How it works

Glow sticks emit light when two chemicals are mixed. The sticks consist of a tiny, brittle container within a flexible outside container. Each container holds a different solution. When the outer container is flexed, the inner container breaks, allowing the solutions to combine, causing the necessary chemical reaction. After breaking, the tube is shaken to thoroughly mix the two components.

Potential dangers

In glow sticks, phenol is produced as a byproduct. It is advisable to keeps the mixture away from skin and to prevent accidental ingestion if the glow stick case splits or breaks. If spilled on skin, the chemicals could cause slight skin irritation, swelling, or, in extreme circumstances, vomiting and nausea. Some of the chemicals used in older glow sticks were thought to be potential carcinogens.[10] The sensitizers used are polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, a class of compounds known for their carcinogenicity.

Chemistry

The glow stick contains two chemicals and a suitable dye (sensitizer, or fluorophor). The chemicals inside the plastic tube are a mixture of the dye and diphenyl oxalate. The chemical in the glass vial is hydrogen peroxide. By mixing the peroxide with the phenyl oxalate ester, a chemical reaction takes place, yielding two molecules of phenol and one molecule of peroxyacid ester (1,2-dioxetanedione).[11] The peroxyacid decomposes spontaneously to carbon dioxide, releasing energy that excites the dye, which then relaxes by releasing a photon. The wavelength of the photon—the color of the emitted light—depends on the structure of the dye. The reaction releases energy mostly as light, with very little heat.[12] The reason for this is that the reverse 2+2 photocycloaddition of 1,2-dioxetanedione is a forbidden transition (it violates Woodward–Hoffmann rules) and cannot proceed through a regular thermal mechanism.

By adjusting the concentrations of the two chemicals, manufacturers can produce glow sticks that either glow brightly for a short amount of time or more dimly for an extended length of time. This also allows design of glow sticks that perform satisfactorily in hot or cold climates, by compensating for the temperature dependence of reaction. At maximum concentration (typically only found in laboratory settings), mixing the chemicals results in a furious reaction, producing large amounts of light for only a few seconds. Heating a glow stick also causes the reaction to proceed faster and the glow stick to glow more brightly for a brief period. Cooling a glow stick slows the reaction a small amount and causes it to last longer, but the light is dimmer. This can be demonstrated by refrigerating or freezing an active glow stick; when it warms up again, it will resume glowing. The dyes used in glow sticks usually exhibit fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet radiation—even a spent glow stick may therefore shine under a black light.

After activation, the glow sticks gradually shift their emission spectral distribution somewhat towards red. The light intensity is high just after activation, then exponentially decays. Leveling of this initial high output is possible by refrigerating the glow stick before activation.[13]

A combination of two fluorophores can be used, with one in the solution and another incorporated to the walls of the container. This is advantageous when the second fluorophore would degrade in solution or be attacked by the chemicals. The emission spectrum of the first fluorophore and the absorption spectrum of the second one have to largely overlap, and the first one has to emit at shorter wavelength than the second one. A downconversion from ultraviolet to visible is possible, as is conversion between visible wavelengths (e.g., green to orange) or visible to near-infrared. The shift can be as much as 200 nm, but usually the range is about 20-100 nm longer than the absorption spectrum.[14] Glow sticks using this approach tend to have colored containers, due to the dye embedded in the plastic. Infrared glow sticks may appear dark-red to black, as the dyes absorb the visible light produced inside the container and reemit near-infrared.

Fluorophores used

- 9,10-Diphenylanthracene (DPA) emits blue light

- 1-chloro-9,10-diphenylanthracene (1-chloro(DPA)) and 2-chloro-9,10-diphenylanthracene (2-chloro(DPA)) emit blue-green light more efficiently than nonsubstituted DPA

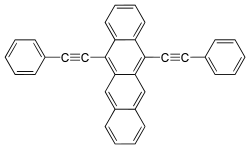

- 9,10-Bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene (BPEA) emits green light with maximum at 486 nm

- 1-Chloro-9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene emits yellow-green light, used in 30-minute high-intensity Cyalume sticks

- 2-Chloro-9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene emits green light, used in 12-hour low-intensity Cyalume sticks

- 1,8-dichloro-9,10-bis(phenylethynyl)anthracene emits yellow light, used in Cyalume sticks

- Rubrene emits orange-yellow at 550 nm

- 2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl 1,4,5,8-tetracarboxynaphthalene diamide emits deep red light, together with DPA is used to produce white or hot-pink light, depending on their ratio

- Rhodamine B emits red light. It is rarely used, as it breaks down in contact with CPPO, shortening the shelf life of the mixture.

- 5,12-Bis(phenylethynyl)naphthacene emits orange light

- Violanthrone emits orange light at 630 nm

- 16,17-(1,2-ethylenedioxy)violanthrone emits red at 680 nm

- 16,17-dihexyloxyviolanthrone emits infrared at 725 nm[15]

- 16,17-butyloxyviolanthrone emits infrared[16]

- N,N'-bis(2,5,-di-tert-butylphenyl)-3,4,9,10-perylenedicarboximide emits red[16]

- 1-N,N-dibutylaminoanthracene emits infrared[16]

- 6-methylacridinium iodide emits infrared[16]

-

9,10-diphenylanthracene yields blue light

-

anthracene.svg.png)

9,10-bis(phenylethynyl) anthracene yields green light

-

1-chloro- 9,10-bis(phenylethynyl) anthracene yields yellow-green light

-

rubrene (5,6,11,12-tetraphenyl naphthacene) yields yellow light

-

5,12-bis(phenylethynyl) naphthacene yields orange light

-

Rhodamine 6G yields orange light

-

Rhodamine B yields red light

See also

References

- ↑ Michael M. Rauhut (1969). "Chemiluminescence from concerted peroxide decomposition reactions (science)". Accounts of Chemical Research 2 (3): 80–87. doi:10.1021/ar50015a003.

- ↑ Elizabeth Wilson (January 18, 1999). "What's that stuff? Light Sticks" (reprint). Chemical & Engineering News 77 (3): 65. doi:10.1021/cen-v077n003.p065.

- ↑ Edwin A. Chandross (1963). "A new chemiluminescent system". Tetrahedron Letters 4 (12): 761–765. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)90712-9.

- ↑ Rood, S. A. "Chapter 4 Post-Legislation Cases" (PDF). Government Laboratory Technology Transfer: Process and Impact Assessment (Doctoral Dissertation). External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ Steve Givens (July 27, 2005). "The great glow stick controversy (Forum Section)". Student Life.

- ↑ Davies, D (1998). "Diver location devices". Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society 28 (3).

- ↑ "What Is Glowsticking?". Glowsticking.com. 2009-09-19. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ "Jai Glow! [PCD vs. Team Ef Em El". YouTube. 2011-02-21. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ Ravetalk (2009-04-30). "BangFace Weekender out of this world |". Ravetalk.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ SCAFO Online Articles

- ↑ http://www.bnl.gov/esh/cms/pdf/peroxides.pdf

- ↑ Kuntzleman, Thomas Scott; Rohrer, Kristen; Schultz, Emeric (2012-06-12). "The Chemistry of Lightsticks: Demonstrations To Illustrate Chemical Processes". Journal of Chemical Education 89 (7): 910–916. doi:10.1021/ed200328d. ISSN 0021-9584.

- ↑ http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf&AD=ADA430634

- ↑ "Chemical lighting device – American Cyanamid Company". Freepatentsonline.com. 1981-02-19. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- ↑ Chemistry Connections: The Chemical Basis of Everyday Phenomena – Kerry K. Karukstis, Gerald R. Van Hecke – Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chemiluminescent Compositions And Methods Of Making And Using Thereof – Patent Application". Faqs.org. 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2012-12-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glowsticks. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||