Glasnevin Cemetery

|

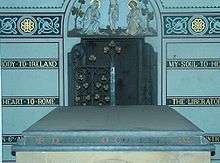

Grave of Michael Collins beside visitors' centre | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1832 |

| Location | Glasnevin, Dublin |

| Country | Ireland |

| Coordinates | 53°22′20″N 6°16′40″W / 53.37222°N 6.27778°WCoordinates: 53°22′20″N 6°16′40″W / 53.37222°N 6.27778°W |

| Type | Public |

| Size | 124 acres (50 ha) |

| Number of interments | 1.5 million |

| Find a Grave | Glasnevin Cemetery at Find a Grave |

Glasnevin Cemetery (Irish: Reilig Ghlas Naíon) is a large cemetery in Glasnevin, Dublin, Ireland which opened in 1832.[1]

History and description

Prior to the establishment of Glasnevin Cemetery, Irish Catholics had no cemeteries of their own in which to bury their dead and, as the repressive Penal Laws of the eighteenth century placed heavy restrictions on the public performance of Catholic services, it had become normal practice for Catholics to conduct a limited version of their own funeral services in Protestant churchyards or graveyards. This situation continued until an incident at a funeral held at St. Kevin's Churchyard in 1823 provoked public outcry when a Protestant sexton reprimanded a Catholic priest for proceeding to perform a limited version of a funeral mass.[2] The outcry prompted Daniel O'Connell, champion of Catholic rights, to launch a campaign and prepare a legal opinion proving that there was actually no law passed forbidding praying for a dead Catholic in a graveyard. O'Connell pushed for the opening of a burial ground in which both Irish Catholics and Protestants could give their dead dignified burial.

Glasnevin Cemetery was consecrated and opened to the public for the first time on 21 February 1832. The first burial, that of eleven-year-old Michael Carey from Francis Street in Dublin, took place on the following day in a section of the cemetery known as Curran's Square. The cemetery was initially known as Prospect Cemetery, a name chosen from the townland of Prospect, which surrounded the cemetery lands. Originally covering nine acres of ground, the area of the cemetery has now grown to approximately 124 acres. This includes its expansion on the southern side of the Finglas Road with the section called St. Paul's. The option of cremation has been provided since March 1982.

Glasnevin Cemetery remains under the care of the Dublin Cemeteries Committee. The development of the cemetery is an ongoing task with major expansion and refurbishment work being carried out at the present time.

The Catholic Mass is celebrated by members of the parish clergy every Sunday at 9.45 a.m. The annual blessing of the graves takes place each summer as it has done since the foundation of the cemetery in 1832.[3]

Location

The cemetery is located in Glasnevin, Dublin, in two parts. The main part, with its trademark high walls and watchtowers, is located on one side of the road from Finglas to the city centre, while the other part, "St. Paul's," is located across the road and beyond a green space, between two railway lines. The Glasnevin Trust Museum was designed by A&D Wejchert & Partners Architects.

Features

Memorials and graves

The cemetery contains historically notable monuments and the graves of many of Ireland's most prominent national figures. These include the graves of Daniel O'Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell, Michael Collins, Éamon de Valera, Arthur Griffith, Maude Gonne, Kevin Barry, Roger Casement, Constance Markievicz, Pádraig Ó Domhnaill, Seán MacBride, Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa, Frank Duff, Brendan Behan, Christy Brown and Luke Kelly of the Dubliners.

In 1993 a mass grave at the site of a Magdalene laundry, institutions ostensibly used to house "fallen women", was discovered after the convent which ran the laundry sold the land to a property developer. The Sisters from the Convent arranged to have the remains cremated and reburied in a mass grave at Glasnevin Cemetery, splitting the cost of the reburial with the developer who had bought the land.[4]

The cemetery also offers a view of the changing style of death monuments in Ireland over the last 200 years: from the austere, simple, high stone erections of the period up until the 1860s, to the elaborate Celtic crosses of the nationalistic revival from the 1860s to the 1960s, to the plain Italian marble of the late 20th century.

The high wall with watch-towers surrounding the main part of the cemetery was built to deter bodysnatchers, who were active in Dublin in the 18th and early 19th centuries. The watchmen also had a pack of blood-hounds who roamed the cemetery at night. Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, when questioned in Parliament on the activities of the body-snatchers, admitted that it was, indeed, a "grave matter".[5]

In 2009, Glasnevin Trust in cooperation with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) began identifying the 208 graves of Irish service personnel who died while serving in the Commonwealth forces during the two world wars. These names are inscribed on two memorials, rededicated and relocated in 2011 to near the main entrance.[6] A Cross of Sacrifice was erected in the cemetery, in a joint Irish-British commemoration ceremony, to mark the First World War centenary.[7]

Angels plot

Glasnevin is one of the few cemeteries that allowed stillborn babies to be buried in consecrated ground and contains an area called the Angels Plot.[8]

Crematorium

In 1982, a crematorium was constructed within the cemetery grounds by Glasnevin Trust. Since then, the service has been used for people of various religious denominations who wished to be cremated.[9] Boyzone singer Stephen Gately was cremated at Glasnevin Crematorium within the cemetery grounds in October 2009.

In literature

Glasnevin Cemetery is the setting for the "Hades" episode in James Joyce's Ulysses, and referenced by Idris Davies in his poem Eire.

Shane MacThomais, the cemetery's historian, was author and contributor to a number of published works on the cemetery, prior to his death in March 2014.[10][11][12][13]

References

- ↑ "Glasnevin Trust – Cemetery History". Glasnevintrust.ie. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ "Glasnevin – Daniel O'Connell". Glasnevin Trust. 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2010. pg 2 of 3

- ↑ "Our Parish – Glasnevin Cemetery". Iona Road Parish Website. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ Mary Raftery (8 June 2011). "Ireland's Magdalene laundries scandal must be laid to rest". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ Irish Times, 4 December 1928, p. 4

- ↑ "Glasnevin Trust & Commonwealth War Graves Commission erect 39 gravestones...". Glasnevin Trust. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "31 July 2014: Dedication of Cross of Sacrifice, Glasnevin Cemetery". Decade of Centenaries. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ "Angels Memory Garden – Glasnevin". Infant Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ "Glasnevin Crematorium". Glasnevin Trust. 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ↑ "Well-known historian Shane MacThomais has died". Independent News and Media. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ "Glasnevin historian Shane MacThomais dies". Journal.ie. 21 March 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ "Mercier Press – Books and authors – Glasnevin Cemetery & Shane MacThomáis". Mercier Press. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ↑ Barbara Scully (27 February 2012). "Dead Interesting: Stories from the Graveyards of Dublin". Writing.ie Magazine. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Glasnevin Cemetery. |

- Official website

- Companion sites irishgraves.com and deadireland.com

- Burial Records from Glasnevin Cemetery Interment.net

- Cemetery Details. Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

.jpg)