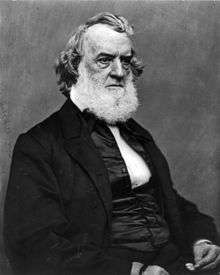

Gideon Welles

| Gideon Welles | |

|---|---|

Gideon Welles in c. 1855–65 | |

| 24th United States Secretary of the Navy | |

|

In office March 7, 1861 – March 4, 1869 | |

| President |

Abraham Lincoln Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Isaac Toucey |

| Succeeded by | Adolph E. Borie |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 1, 1802 Glastonbury, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died |

February 11, 1878 (aged 75) Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Political party | Democrat, Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Jane Hale Welles[1] |

| Children |

Edgar Thaddeus Welles[2] Thomas Glastonbury Welles John Arthur Welles Herbert Welles Samuel Welles Edward Gideon Welles Anna Jane Welles Mary Juanita Welles |

| Alma mater | Military Academy at Norwich, Vermont |

| Profession | Politician, lawyer, writer, journalist |

| Signature |

|

Gideon Welles (July 1, 1802 – February 11, 1878) was the United States Secretary of the Navy from 1861 to 1869, a cabinet post he was given after supporting Lincoln in the 1860 election. Although opposed to the Union blockade of Southern ports, he duly carried out his part of the Anaconda Plan, largely sealing-off the Confederate coastline and preventing the exchange of cotton for war supplies. This is viewed as a major cause of Union victory in the Civil War, and his achievement in expanding the Navy almost tenfold was widely praised. Welles was also instrumental in the Navy's creation of the Medal of Honor.

Early political career

Gideon Welles, the son of Samuel Welles and Ann Hale,[3] was born on July 1, 1802, in Glastonbury, Connecticut.[4] His father was a shipping merchant and fervent Jeffersonian;[5] he was a member of the Convention, which formed the first state Connecticut Constitution in 1818 that abolished the colonial charter and officially severed the political ties to England. This constitution is also notable for having reversed the earlier Orders and provided for freedom of religion. He was a member of the seventh generation of his family in America. His original immigrant ancestor was Thomas Welles,[6][7] who arrived in 1635 and was the only man in Connecticut's history to hold all four top offices: governor, deputy governor, treasurer, and secretary. He was also the transcriber of the Fundamental Orders. Welles was the second great grandson of Capt. Samuel Welles and Ruth (Rice) Welles, the daughter of Edmund Rice, a 1638 immigrant to Sudbury and founder of Marlborough, Massachusetts.[8]

He married on June 16, 1835, at Lewiston, Mifflin County, Pennsylvania, Mary Jane Hale,[1] who was born on June 18, 1817, in Glastonbury, Connecticut, the daughter of Elias White Hale and Jane Mullhallan. Her father, Elias, graduated from Yale College in 1794 and practiced law in Mifflin and Centre Counties, Pennsylvania.[9] She died on February 28, 1886, in Hartford, Connecticut, and was buried next to her husband in Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford. Gideon and Mary Jane were the parents of six children.

He was educated at the Episcopal Academy at Cheshire, Connecticut, and earned a degree at the American Literary, Scientific, and Military Academy at Norwich, Vt. (later Norwich University).[4] He became a lawyer through the then-common practice of reading the law, but soon shifted to journalism and became the founder and editor of the Hartford Times in 1826. After successfully gaining admission, from 1827–1835, he participated in the Connecticut House of Representatives as a Democrat. Following his service in the Connecticut General Assembly, he served in various posts, including State Controller of Public Accounts in 1835, Postmaster of Hartford (1836–41), and Chief of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing for the Navy (1846–49).[10]

Welles was a Jacksonian Democrat who worked very closely with Martin Van Buren and John Milton Niles. His chief rival in the Connecticut Democratic Party was Isaac Toucey, whom Welles would later replace at the Navy Department. While Welles dutifully supported James K. Polk in the 1844 election, he would abandon the Democrats in 1848 to support Van Buren's Free Soil campaign.

Mainly because of his strong anti-slavery views, Welles shifted allegiance in 1854 to the newly established Republican Party and founded a newspaper in 1856 (the Hartford Evening Press) that would espouse Republican ideals for decades thereafter. Welles' strong support of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 made him the logical candidate from New England for Lincoln's cabinet, and in March 1861, Lincoln named Welles his Secretary of the Navy.

Tenure in Lincoln's Cabinet

(People in the image are clickable.)

- ^ "Art & History: First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Lincoln". U.S. Senate. Retrieved August 2, 2013. Lincoln met with his cabinet on July 22, 1862, for the first reading of a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation. Sight measurement. Height: 108 inches (274.32 cm) Width: 180 inches (457.2 cm)

An 1864 cartoon featuring Welles, William P. Fessenden, Edwin M. Stanton, Abraham Lincoln and William H. Seward takes a swing at the Lincoln administration.

Welles found the Naval Department in disarray, with Southern officers resigning en masse. His first major action was to dispatch the Navy's most powerful warship, the USS Powhatan, to relieve Fort Sumter on Lincoln's instructions. Unfortunately, Secretary of State Seward had just ordered the Powhatan to Fort Pickens, Florida on his own authority, ruining whatever chance Major Robert Anderson had of withstanding the assault. Several weeks later, when Seward argued for a blockade of Southern ports, Welles argued vociferously against the action but was eventually overruled by Lincoln. Despite his misgivings, Welles' efforts to rebuild the Navy and implement the blockade proved extraordinarily effective. From 76 ships and 7,600 sailors in 1861, the Navy expanded almost tenfold by 1865. His implementation of the Naval portion of the Anaconda Plan strongly weakened the Confederacy's ability to finance the war by limiting the cotton trade, and while never completely effective in sealing off all 3,500 miles of Southern coastline, it was a major contribution towards Northern victory. Lincoln nicknamed Welles his "Neptune."

At the start of the war, David Dixon Porter wrote Welles that "the present allowance of crews . . . is for peace establishment and is not suited at all to times of war." On another occasion, Porter told Welles that his own vessel lacked coal and that small steamers of shallow draft were required to make the blockade effective. From Mobile to the Mississippi River, numerous inlets allowed small Confederate craft to slip through the Federal blockade.[11]

Despite his successes, Welles was never at ease in the Cabinet. His anti-English sentiments caused him to clash with Seward, and Welles's conservative stances led to arguments with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase and War Secretary Edwin M. Stanton.

Tenure in Johnson's Cabinet

After Lincoln's assassination, Welles was retained by President Andrew Johnson as Secretary of the Navy. In 1866, Welles, along with Seward, was instrumental in launching the National Union Party as a third party alternative supportive of Johnson's reconciliation policies. Welles also played a prominent part in Johnson's ill-fated "Swing Around the Circle" campaign that fall. Although Welles admitted in his diary that he was dismayed by Johnson's behavior on the trip, particularly the president's penchant for invective and engaging directly with hecklers, Welles remained loyal to Johnson to the end, even congratulating him in 1875 when Johnson, then an ex-president, launched a comeback political bid with his election to the U.S. Senate from Tennessee.

Welles ultimately left the Cabinet on March 3, 1869, having returned to the Democratic Party after disagreeing with Andrew Johnson's reconstruction policies but supporting him during his impeachment trial.

Later life and death

After leaving politics, Welles returned to Connecticut and to writing, editing his journals, and authoring several books before his death, including a biography, Lincoln and Seward, published in 1874.[4]

He was a Third Class Companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. While the Loyal Legion did consist predominantly of Union officers who had served in the American Civil War the Order's constitution provided for honorary members (i.e. Third Class Companions) who were civilians who had made significant contributions to the war effort. Welles was also instrumental in the Navy's creation of the Medal of Honor.[12]

Towards the end of 1877, his health began to wane. A streptococcal infection of the throat killed Gideon Welles at the age of seventy-five on February 12, 1878. [4] His body was interred at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.[13]

The Diary of Gideon Welles

Welles' three-volume diary, documenting his Cabinet service from 1861–1869, is an invaluable archive for Civil War scholars and students of Lincoln alike, allowing readers rare insight into the complex struggles, machinations, and inter-relational strife within the President's War Cabinet. Although offering a unique and quite nonpareil portrayal of the immense personalities and problems facing the men who led the Union to ultimate victory, the first edition (published in 1911) suffers from rewrites by Welles himself and, after his death, by his son; the 1960 edition is drawn directly from his original manuscript. The 1911 version of his diary may be found on Google Books: Vol. I (1861 – March 30, 1864), Vol. II (April 1, 1864 – December 31, 1866), Vol. III (January 1, 1867 – June 6, 1869).

Posthumous dedications

Two ships have been named USS Welles in his honor. The Dining Commons at Cheshire Academy and the Gideon Welles School in Glastonbury, Connecticut, are also named after him. In the Lincoln Square neighborhood of Chicago, the Welles Park was dedicated in honor of Gideon Welles in 1910,[14] and more recently, an adjacent restaurant has also been named after Gideon Welles[15] which opened in 2014.

Legacy

In an interview with Dick Cavett on The Dick Cavett Show, actor and director Orson Welles revealed, nonchalantly, that he was the great-grandson of Gideon Welles, and had known a dinner party hostess Cornelia Gray Lunt from the American Civil War era familiar with his great-grandfather Gideon. This relation has, however, become a debunked myth, and this false tale possibly originated from that particular appearance on Cavett's show.[16]

Notes

- 1 2 "Obituary: Mrs. Gideon Welles". New York Times. March 4, 1886. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ↑ Obituary: "Edgar T. Welles" New York Times. August 23, 1914.

- ↑ Hale, p.113

- 1 2 3 4 "Obituary: Gideon Welles". New York Times. February 12, 1878. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ↑ Niven, p.6

- ↑ Norton, pp. 19–21

- ↑ Niven, p.7

- ↑ "Gideon Welles in ERA database". Edmund Rice (1638) Association, Inc. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

- ↑ Niven, p.16

- ↑ "Gideon Welles papers, 1777–1911". Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. 1997, revised April 2010. Retrieved October 27, 2010. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Winters, p. 47

- ↑ "The Navy's Medal of Honor". Department of the Navy – Naval Historical Center. October 30, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- ↑ Gideon Welles at Find A Grave

- ↑ http://www.chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/Welles-Park/

- ↑ http://www.gideonchicago.com

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r1fauAc48tA

References

- Boulard, Garry "The Swing Around the Circle—Andrew Johnson and the Train Ride that Destroyed a Presidency" (iUniverse, 2008)

- Hale, Oscar Fitzalan. Ancestry and descendants of Josiah Hale: fifth in descent from Samuel Hale of Hartford, Connecticut, 1637 Rutland, Vermont: The Tuttle Company, 1909.

- Niven, John. Gideon Welles; Lincoln's Secretary of the Navy Publisher: Oxford University Press US, 1973. ISBN 0-19-501693-9

- Norton, Frederick Calvin The governors of Connecticut: biographies of the chief executives of the commonwealth that gave to the world the first written constitution known to history, Publisher Connecticut Magazine Co., 1905.

- Siemiatkoski, Donna Holt. The Descendants of Governor Thomas Welles of Connecticut, 1590–1658, and His Wife, Alice Tomes Baltimore: Publisher, Gateway Press, 1990.

- John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-1725-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gideon Welles. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gideon Welles |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Welles, Gideon. |

- Lincoln and Seward: by Gideon Welles, New York: Publisher, Sheldon and Company, 1874.

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: Gideon Welles

- Gideon Welles at the Naval Historical Center

- Welles Family Association, Inc.

- Biographical sketch of Thomas Welles Connecticut State Library

- Lost Letters of Gideon Welles

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Isaac Toucey |

United States Secretary of the Navy March 7, 1861 – March 4, 1869 |

Succeeded by Adolph E. Borie |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|