Gibbs isotherm

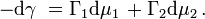

The Gibbs adsorption isotherm for multicomponent systems is an equation used to relate the changes in concentration of a component in contact with a surface with changes in the surface tension, which results in a corresponding change in surface energy. For a binary system, the Gibbs adsorption equation in terms of surface excess is:

where

is the surface tension,

is the surface tension, i is the surface excess of component i,

i is the surface excess of component i, i is the chemical potential of component i.

i is the chemical potential of component i.

Adsorption

Different influences at the interface may cause changes in the composition of the near-surface layer[1] Substances may either accumulate near the surface or, conversely, move into the bulk.[1] The movement of the molecules characterizes the phenomena of adsorption. Adsorption influences changes in surface tension and colloid stability. Adsorption layers at the surface of a liquid dispersion medium may affect the interactions of the dispersed particles in the media and consequently these layers may play crucial role in colloid stability[2] The adsorption of molecules of liquid phase at an interface occurs when this liquid phase is in contact with other immiscible phases that may be gas, liquid, or solid[3]

Conceptual explanation of equation

Surface tension describes how difficult it is to extend the area of a surface (by stretching or distorting it). If surface tension is high, there is a large free energy required to increase the surface area, so the surface will tend to contract and hold together like a rubber sheet.

There are various factors affecting surface tension, one of which is that the composition of the surface may be different from the bulk. For example, if water is mixed with a tiny amount of surfactants (for example, hand soap), the bulk water may be 99% water molecules and 1% soap molecules, but the topmost surface of the water may be 50% water molecules and 50% soap molecules. In this case, the soap has a large and positive "surface excess". In other examples, the surface excess may be negative: For example, if water is mixed with an inorganic salt like sodium chloride, the surface of the water is on average less salty and more pure than the bulk average.

Consider again the example of water with a bit of soap. Since the water surface needs to have higher concentration of soap than the bulk, whenever the water's surface area is increased, it is necessary to remove soap molecules from the bulk and add them to the new surface. If the concentration of soap is increased a bit, the soap molecules are more readily available (they have higher chemical potential), so it is easier to pull them from the bulk in order to create the new surface. Since it is easier to create new surface, the surface tension is lowered. The general principle is:

- When the surface excess of a component is positive, increasing the chemical potential of that component reduces the surface tension.

Next consider the example of water with salt. The water surface is less salty than bulk, so whenever the water's surface area is increased, it is necessary to remove salt molecules from the new surface and push them into bulk. If the concentration of salt is increased a bit (raising the salt's chemical potential), it becomes harder to push away the salt molecules. Since it is now harder to create the new surface, the surface tension is higher. The general principle is:

- When the surface excess of a component is negative, increasing the chemical potential of that component increases the surface tension.

The Gibbs isotherm equation gives the exact quantitative relationship for these trends.

Location of surface and defining surface excess

Location of surface

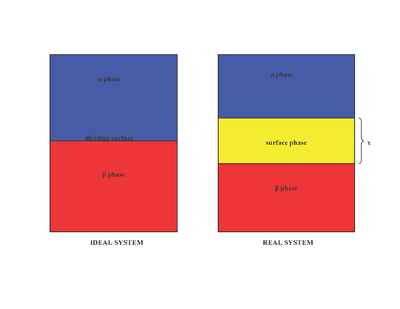

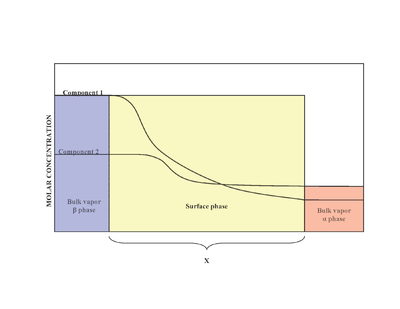

In the presence of two phases (α and β), the surface (surface phase) is located in between the phase α and phase β. Experimentally, it is difficult to determine the exact structure of an inhomogeneous surface phase that is in contact with a bulk liquid phase containing more than one solute.[2] Inhomogeneity of the surface phase is a result of variation of mole ratios.[1] A model proposed by Josiah Willard Gibbs proposed that the surface phase as an idealized model that had zero thickness. In reality, although the bulk regions of α and β phases are constant, the concentrations of components in the interfacial region will gradually vary from the bulk concentration of α to the bulk concentration of β over the distance x. This is in contrast to the idealized Gibbs model where the distance x takes on the value of zero. The diagram to the right illustrates the differences between the real and idealized models.

Definition of surface excess

In the idealized model, the chemical components of the α and β bulk phases remain unchanged except when approaching the dividing surface.[3] The total moles of any component (Examples include: water, ethylene glycol etc.) remains constant in the bulk phases but varies in the surface phase for the real system model as shown below.

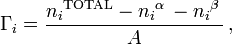

In the real system, however, the total moles of a component varies depending on the arbitrary placement of the dividing surface. The quantitative measure of adsorption of the i-th component is captured by the surface excess quantity.[1] The surface excess represents the difference between the total moles of the i-th component in a system and the moles of the i-th component in a particular phase (either α or β) and is represented by:

where Γi is the surface excess of the i-th component, n are the moles, α and β are the phases, and A is the area of the dividing surface.

Γ represents excess of solute per unit area of the surface over what would be present if the bulk concentration prevailed all the way to the surface, it can be positive, negative or zero. It has units of mol/m2.

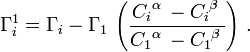

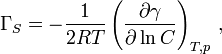

Relative surface excess

Relative Surface Excess quantities are more useful than arbitrary surface excess quantities.[3] The Relative surface excess relates the adsorption at the interface to a solvent in the bulk phase. An advantage of using the relative surface excess quantities is that they don't depend on the location of the dividing surface. The relative surface excess of species i and solvent 1 is therefore:

The Gibbs adsorption isotherm equation

Derivation of the Gibbs adsorption equation

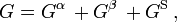

For a two-phase system consisting of the α and β phase in equilibrium with a surface s dividing the phases, the total Gibbs free energy of a system can be written as:

where G is the Gibbs free energy.

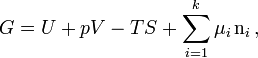

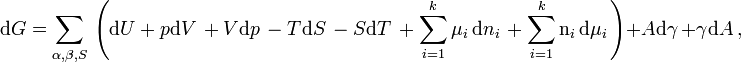

The equation of the Gibbs Adsorption Isotherm can be derived from the “particularization to the thermodynamics of the Euler theorem on homogeneous first-order forms.”[4] The Gibbs free energy of each phase α, phase β, and the surface phase can be represented by the equation:

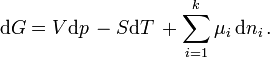

where U is the internal energy, p is the pressure, V is the volume, T is the temperature, S is the entropy, and μi is the chemical potential of the i-th component.

By taking the total derivative of the Euler form of the Gibbs equation for the α phase, β phase and the surface phase:

where A is the cross sectional area of the dividing surface, and γ is the surface tension.

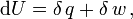

For reversible processes, the first law of thermodynamics requires that:

where q is the heat energy and w is the work.

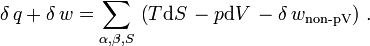

Substituting the above equation into the total derivative of the Gibbs energy equation and by utilizing the result γdA is equated to the non-pressure volume work when surface energy is considered:

by utilizing the fundamental equation of Gibbs energy of a multicomponent system:

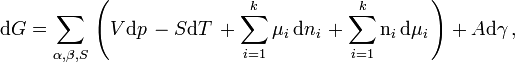

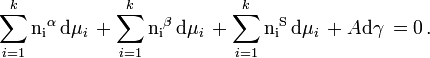

The equation relating the α phase, β phase and the surface phase becomes:

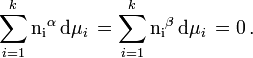

When considering the bulk phases (α phase, β phase), at equilibrium at constant temperature and pressure the Gibbs–Duhem equation requires that:

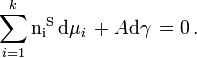

The resulting equation is the Gibbs adsorption isotherm equation:

The Gibbs adsorption isotherm is an equation which could be considered an adsorption isotherm that connects surface tension of a solution with the concentration of the solute.

For a binary system containing two components the Gibbs Adsorption Equation in terms of surface excess is:

Relation between surface tension and the surface excess concentration

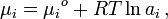

The chemical potential of species i in solution depends on the activity a using the following equation:[2]

where μi is the chemical potential of the i-th component, μio is the chemical potential of the i-th component at a reference state, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, and ai is the activity of the i-th component.

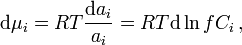

Differentiation of the chemical potential equation results in:

where f is the activity coefficient of component i, and C is the concentration of species i in the bulk phase.

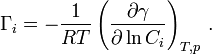

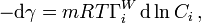

If the solutions in the α and β phases are dilute (rich in one particular component i) then activity coefficient of the component i approaches unity and the Gibbs isotherm becomes:

The above equation assumes the interface to be bidimensional, which is not always true. Further models, such as Guggenheim's, correct this flaw.

Ionic dissociation effects

Gibbs equation for electrolyte adsorption

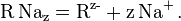

Consider a system composed of water that contains an organic electrolyte RNaz and an inorganic electrolyte NaCl that both dissociate completely such that:

The Gibbs Adsorption equation in terms of the relative surface excess becomes:

The Relation Between Surface Tension and The Surface Excess Concentration becomes:

where m is the coefficient of the Gibbs adsorption.[3] Values of m are calculated using the Double layer (interfacial) models of Helmholtz, Gouy, and Stern.

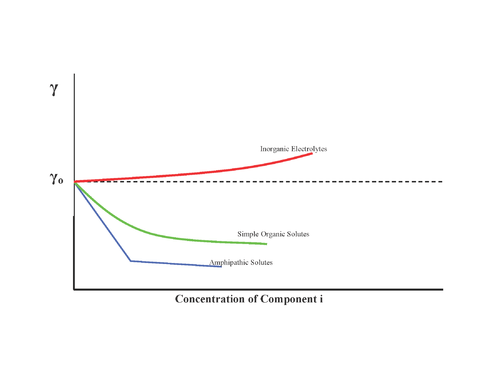

Substances can have different effects on surface tension as shown :

- No effect, for example sugar

- Increase of surface tension, inorganic salts

- Decrease surface tension progressively, alcohols

- Decrease surface tension and, once a minimum is reached, no more effect: surfactants

Therefore inorganic salts have negative surface concentrations (which is logical, because they have strong attractions with the solvent) and surfactants have positive surface concentrations: they adsorb on the interface.

A method for determining surface concentrations is needed in order to prove the validity of the model: two different techniques are normally used: ellipsometry and following the decay of 14C present in the surfactant molecules.

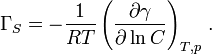

Gibbs isotherm for ionic surfactants

Ionic surfactants require special considerations, as they are electrolytes:

- In absence of extra electrolytes

where  refers to the surface concentration of surfactant molecules, without considering the counter ion.

refers to the surface concentration of surfactant molecules, without considering the counter ion.

- In presence of added electrolytes

Experimental methods

The extent of adsorption at a liquid interface can be evaluated using the surface tension concentration data and the Gibbs adsorption equation.[3] The microtome blade method is used to determine the weight and molal concentration of an interface. The method involves attaining a one square meter portion of air-liquid interface of binary solutions using a microtome blade.

Another method that is used to determine the extent of adsorption at an air-water interface is the emulsion technique, which can be used to estimate the relative surface excess with respect to water.[3]

Additionally, the Gibbs surface excess of a surface active component for an aqueous solution can be found using the radioactive tracer method. The surface active component is usually labeled with carbon-14 or sulfur-35.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Shchukin, E.D., Pertsov, A.V., Amelina E.A. and Zelenev, A.S. Colloid and Surface Chemistry. 1st ed. Mobius D. and Miller R. Vol. 12. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V. 2001.

- 1 2 3 Hiemenz, Paul C. and Rajagopalan, Raj. Principles of Colloid and Surface Chemistry. 3rd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc, 1997.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chattoraj, D.K. and Birdi, K.S. Adsorption and the Gibbs Surface Excess. New York: Plenum Publishing Company, 1984.

- ↑ Callen, Herbert B. Thermodynamics and an Introduction to Thermostatics. 2nd ed. Canada: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1985.