Gibbs–Duhem equation

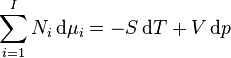

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs–Duhem equation describes the relationship between changes in chemical potential for components in a thermodynamical system:[1]

where  is the number of moles of component

is the number of moles of component  ,

,  the infinitesimal increase in chemical potential for this component,

the infinitesimal increase in chemical potential for this component,  the entropy,

the entropy,  the absolute temperature,

the absolute temperature,  volume and

volume and  the pressure. It shows that in thermodynamics intensive properties are not independent but related, making it a mathematical statement of the state postulate. When pressure and temperature are variable, only

the pressure. It shows that in thermodynamics intensive properties are not independent but related, making it a mathematical statement of the state postulate. When pressure and temperature are variable, only  of

of  components have independent values for chemical potential and Gibbs' phase rule follows. The law is named after Josiah Willard Gibbs and Pierre Duhem.

components have independent values for chemical potential and Gibbs' phase rule follows. The law is named after Josiah Willard Gibbs and Pierre Duhem.

The Gibbs−Duhem equation cannot be used for small thermodynamic systems due to the influence of surface effects and other microscopic phenomena.[2]

Derivation

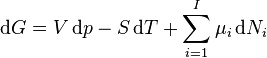

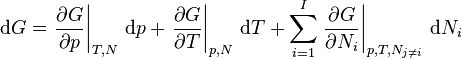

Deriving the Gibbs–Duhem equation from the fundamental thermodynamic equation is straightforward.[3] The total differential of the Gibbs free energy  in terms of its natural variables is

in terms of its natural variables is

.

.

Since the Gibbs free energy is the Legendre transformation of the internal energy, the derivatives can be replaced by its definitions transforming the above equation into:[4]

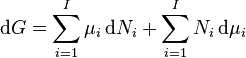

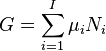

As shown in the Gibbs free energy article, the chemical potential is simply another name for the partial molar (or just partial, depending on the units of N) Gibbs free energy, thus the gibbs free energy of a system can be calculated by collecting moles together carefully at a specified T, P and at a constant molar ratio composition (so that the chemical potential doesn't change as the moles are added together), i.e.

.

.

The total differential of this expression is[4]

By subtracting the two expressions for the total differential of the Gibbs free energy gives the Gibbs–Duhem relation:[4]

Applications

By normalizing the above equation by the extent of a system, such as the total number of moles, the Gibbs–Duhem equation provides a relationship between the intensive variables of the system. For a simple system with  different components, there will be

different components, there will be  independent parameters or "degrees of freedom". For example, if we know a gas cylinder filled with pure nitrogen is at room temperature (298 K) and 25 MPa, we can determine the fluid density (258 kg/m3), enthalpy (272 kJ/kg), entropy (5.07 kJ/kg-K) or any other intensive thermodynamic variable.[5] If instead the cylinder contains a nitrogen/oxygen mixture, we require an additional piece of information, usually the ratio of oxygen-to-nitrogen.

independent parameters or "degrees of freedom". For example, if we know a gas cylinder filled with pure nitrogen is at room temperature (298 K) and 25 MPa, we can determine the fluid density (258 kg/m3), enthalpy (272 kJ/kg), entropy (5.07 kJ/kg-K) or any other intensive thermodynamic variable.[5] If instead the cylinder contains a nitrogen/oxygen mixture, we require an additional piece of information, usually the ratio of oxygen-to-nitrogen.

If multiple phases of matter are present, the chemical potentials across a phase boundary are equal.[6] Combining expressions for the Gibbs–Duhem equation in each phase and assuming systematic equilibrium (i.e. that the temperature and pressure is constant throughout the system), we recover the Gibbs' phase rule.

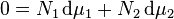

One particularly useful expression arises when considering binary solutions.[7] At constant P (isobaric) and T (isothermal) it becomes:

or, normalizing by total number of moles in the system  , substituting in the definition of activity coefficient

, substituting in the definition of activity coefficient  and using the identity

and using the identity  :

:

This equation is instrumental in the calculation of thermodynamically consistent and thus more accurate expressions for the vapor pressure of a fluid mixture from limited experimental data.

See also

References

- ↑ A to Z of Thermodynamics Pierre Perrot ISBN 0-19-856556-9

- ↑ Stephenson, J. (1974). "Fluctuations in Particle Number in a Grand Canonical Ensemble of Small Systems". American Journal of Physics 42 (6): 478–471. doi:10.1119/1.1987755.

- ↑ Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, 3rd Edition Michael J. Moran and Howard N. Shapiro, p. 538 ISBN 0-471-07681-3

- 1 2 3 Salzman, William R. (2001-08-21). "Open Systems". Chemical Thermodynamics. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Calculated using REFPROP: NIST Standard Reference Database 23, Version 8.0

- ↑ Fundamentals of Engineering Thermodynamics, 3rd Edition Michael J. Moran and Howard N. Shapiro, p. 710 ISBN 0-471-07681-3

- ↑ The Properties of Gases and Liquids, 5th Edition Poling, Prausnitz and O'Connell, p. 8.13, ISBN 0-07-011682-2

- ↑ Chemical Thermodynamics of Materials, 2004 Svein Stølen, p. 79, ISBN 0-471-49230-2