Jamshīd al-Kāshī

| Persian Muslim scholar Ghiyāth al-Dīn Jamshīd Kāshānī | |

|---|---|

| Title | al-Kashi |

| Born | 1380 |

| Died | 22 June 1429 |

| Ethnicity | Persian |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Iran |

| Religion | Islam |

| Main interest(s) | Astronomy, Mathematics |

| Notable idea(s) | Pi decimal determination to the 16th place |

| Notable work(s) | Sullam al-Sama |

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Jamshīd Masʿūd al-Kāshī (or al-Kāshānī)[1] (Persian: غیاث الدین جمشید کاشانی Ghiyās-ud-dīn Jamshīd Kāshānī) (c. 1380 Kashan, Iran – 22 June 1429 Samarkand, Transoxania) was a Persian astronomer and mathematician.

Much of al-Kāshī's work was not brought to Europe, and much, even the extant work remains unpublished in any form.[2]

Biography

Al-Kashi was one of the best mathematicians in the history of the Persian Empire. He was born in 1380, in Kashan, in central Iran. This region was controlled by Tamerlane, better known as Timur.

The situation changed for the better when Timur died in 1405, and his son, Shah Rokh, ascended into power. Shah Rokh and his wife, Goharshad, a Persian princess, were very interested in the sciences, and they encouraged their court to study the various fields in great depth. Consequently, the period of their power became one of many scholarly accomplishments. This was the perfect environment for al-Kashi to begin his career as one of the world’s greatest mathematicians.

Eight years after he came into power in 1409, their son, Ulugh Beg, founded an institute in Samarkand which soon became a prominent university. Students from all over the Middle East, and beyond, flocked to this academy in the capital city of Ulugh Beg’s empire. Consequently, Ulugh Beg gathered many great mathematicians and scientists of the Middle East. In 1414, al-Kashi took this opportunity to contribute vast amounts of knowledge to his people. His best work was done in the court of Ulugh Beg.

Al-Kashi was still working on his book, called “Risala al-watar wa’l-jaib” meaning “The Treatise on the Chord and Sine”, when he died, probably in 1429. Some scholars believe that Ulugh Beg may have ordered his murder, while others say he died a natural death.

Astronomy

Khaqani Zij

Al-Kashi produced a Zij entitled the Khaqani Zij, which was based on Nasir al-Din al-Tusi's earlier Zij-i Ilkhani. In his Khaqani Zij, al-Kashi thanks the Timurid sultan and mathematician-astronomer Ulugh Beg, who invited al-Kashi to work at his observatory (see Islamic astronomy) and his university (see Madrasah) which taught Shia theology as well as Shia science. Al-Kashi produced sine tables to four sexagesimal digits (equivalent to eight decimal places) of accuracy for each degree and includes differences for each minute. He also produced tables dealing with transformations between coordinate systems on the celestial sphere, such as the transformation from the ecliptic coordinate system to the equatorial coordinate system.[3]

Astronomical Treatise on the size and distance of heavenly bodies

He wrote the book Sullam al-Sama on the resolution of difficulties met by predecessors in the determination of distances and sizes of heavenly bodies such as the Earth, the Moon, the Sun and the Stars.

Treatise on Astronomical Observational Instruments

In 1416, al-Kashi wrote the Treatise on Astronomical Observational Instruments, which described a variety of different instruments, including the triquetrum and armillary sphere, the equinoctial armillary and solsticial armillary of Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi, the sine and versine instrument of Urdi, the sextant of al-Khujandi, the Fakhri sextant at the Samarqand observatory, a double quadrant Azimuth-altitude instrument he invented, and a small armillary sphere incorporating an alhidade which he invented.[4]

Plate of Conjunctions

Al-Kashi invented the Plate of Conjunctions, an analog computing instrument used to determine the time of day at which planetary conjunctions will occur,[5] and for performing linear interpolation.[6]

Planetary computer

Al-Kashi also invented a mechanical planetary computer which he called the Plate of Zones, which could graphically solve a number of planetary problems, including the prediction of the true positions in longitude of the Sun and Moon,[6] and the planets in terms of elliptical orbits;[7] the latitudes of the Sun, Moon, and planets; and the ecliptic of the Sun. The instrument also incorporated an alhidade and ruler.[8]

Mathematics

Law of cosines

In French, the law of cosines is named Théorème d'Al-Kashi (Theorem of Al-Kashi), as al-Kashi was the first to provide an explicit statement of the law of cosines in a form suitable for triangulation.

The Treatise of Chord and Sine

In The Treatise on the Chord and Sine, al-Kashi computed sin 1° to nearly as much accuracy as his value for π, which was the most accurate approximation of sin 1° in his time and was not surpassed until Taqi al-Din in the sixteenth century. In algebra and numerical analysis, he developed an iterative method for solving cubic equations, which was not discovered in Europe until centuries later.[3]

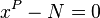

A method algebraically equivalent to Newton's method was known to his predecessor Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī. Al-Kāshī improved on this by using a form of Newton's method to solve  to find roots of N. In western Europe, a similar method was later described by Henry Biggs in his Trigonometria Britannica, published in 1633.[9]

to find roots of N. In western Europe, a similar method was later described by Henry Biggs in his Trigonometria Britannica, published in 1633.[9]

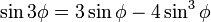

In order to determine sin 1°, al-Kashi discovered the following formula often attributed to François Viète in the sixteenth century:[10]

The Key to Arithmetic

Computation of 2π

In his numerical approximation, he correctly computed 2π (or  ) to 9 sexagesimal digits[11] in 1424,[3] and he converted this estimate of 2π to 16 decimal places of accuracy.[12] This was far more accurate than the estimates earlier given in Greek mathematics (3 decimal places by Ptolemy, 150 BC), Chinese mathematics (7 decimal places by Zu Chongzhi, 480 Ad) or Indian mathematics (11 decimal places by Madhava of Sangamagrama, c. 1400). The accuracy of al-Kashi's estimate was not surpassed until Ludolph van Ceulen computed 20 decimal places of π 180 years later.[3] Al-Kashi's goal was to compute the circle constant so precisely that the circumference of the largest possible circle (ecliptica) could be computed with highest desirable precision (the diameter of a hair).

) to 9 sexagesimal digits[11] in 1424,[3] and he converted this estimate of 2π to 16 decimal places of accuracy.[12] This was far more accurate than the estimates earlier given in Greek mathematics (3 decimal places by Ptolemy, 150 BC), Chinese mathematics (7 decimal places by Zu Chongzhi, 480 Ad) or Indian mathematics (11 decimal places by Madhava of Sangamagrama, c. 1400). The accuracy of al-Kashi's estimate was not surpassed until Ludolph van Ceulen computed 20 decimal places of π 180 years later.[3] Al-Kashi's goal was to compute the circle constant so precisely that the circumference of the largest possible circle (ecliptica) could be computed with highest desirable precision (the diameter of a hair).

Decimal fractions

In discussing decimal fractions, Struik states that (p. 7):[13]

"The introduction of decimal fractions as a common computational practice can be dated back to the Flemish pamphlet De Thiende, published at Leyden in 1585, together with a French translation, La Disme, by the Flemish mathematician Simon Stevin (1548-1620), then settled in the Northern Netherlands. It is true that decimal fractions were used by the Chinese many centuries before Stevin and that the Persian astronomer Al-Kāshī used both decimal and sexagesimal fractions with great ease in his Key to arithmetic (Samarkand, early fifteenth century).[14]"

Khayyam's triangle

In considering Pascal's triangle, known in Persia as "Khayyam's triangle" (named after Omar Khayyám), Struik notes that (p. 21):[13]

"The Pascal triangle appears for the first time (so far as we know at present) in a book of 1261 written by Yang Hui, one of the mathematicians of the Song dynasty in China.[15] The properties of binomial coefficients were discussed by the Persian mathematician Jamshid Al-Kāshī in his Key to arithmetic of c. 1425.[16] Both in China and Persia the knowledge of these properties may be much older. This knowledge was shared by some of the Renaissance mathematicians, and we see Pascal's triangle on the title page of Peter Apian's German arithmetic of 1527. After this we find the triangle and the properties of binomial coefficients in several other authors.[17]"

Biographical film

In 2009 IRIB produced and broadcast (through Channel 1 of IRIB) a biographical-historical film series on the life and times of Jamshid Al-Kāshi, with the title The Ladder of the Sky [18][19] (Nardebām-e Āsmān [20]). The series, which consists of 15 parts of each 45 minutes duration, is directed by Mohammad-Hossein Latifi and produced by Mohsen Ali-Akbari. In this production, the role of the adult Jamshid Al-Kāshi is played by Vahid Jalilvand.[21][22][23]

Notes

- ↑ A. P. Youschkevitch and B. A. Rosenfeld. "al-Kāshī (al-Kāshānī), Ghiyāth al-Dīn Jamshīd Masʿūd" Dictionary of Scientific Biography.

- ↑ iranicaonline.org

- 1 2 3 4 O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid Mas'ud al-Kashi", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- ↑ (Kennedy 1961, pp. 104–107)

- ↑ (Kennedy 1947, p. 56)

- 1 2 (Kennedy 1950)

- ↑ (Kennedy 1952)

- ↑ (Kennedy 1951)

- ↑ Ypma, Tjalling J. (December 1995), "Historical Development of the Newton-Raphson Method", SIAM Review (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics) 37 (4): 531–551 [539], doi:10.1137/1037125

- ↑ Marlow Anderson, Victor J. Katz, Robin J. Wilson (2004), Sherlock Holmes in Babylon and Other Tales of Mathematical History, Mathematical Association of America, p. 139, ISBN 0-88385-546-1

- ↑ Al-Kashi, author: Adolf P. Youschkevitch, chief editor: Boris A. Rosenfeld, p. 256

- ↑ The statement that a quantity is calculated to

sexagesimal digits implies that the maximal inaccuracy in the calculated value is less than

sexagesimal digits implies that the maximal inaccuracy in the calculated value is less than  in the decimal system. With

in the decimal system. With  , Al-Kashi has thus calculated

, Al-Kashi has thus calculated  with a maximal error less than

with a maximal error less than  . That is to say, Al-Kashi has calculated

. That is to say, Al-Kashi has calculated  exactly up to and including the 16th place after the decimal separator. For

exactly up to and including the 16th place after the decimal separator. For  expressed exactly up to and including the 18th place after the decimal separator one has:

expressed exactly up to and including the 18th place after the decimal separator one has:  .

. - 1 2 D.J. Struik, A Source Book in Mathematics 1200-1800 (Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1986). ISBN 0-691-02397-2

- ↑ P. Luckey, Die Rechenkunst bei Ğamšīd b. Mas'ūd al-Kāšī (Steiner, Wiesbaden, 1951).

- ↑ J. Needham, Science and civilisation in China, III (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1959), 135.

- ↑ Russian translation by B.A. Rozenfel'd (Gos. Izdat, Moscow, 1956); see also Selection I.3, footnote 1.

- ↑ Smith, History of mathematics, II, 508-512. See also our Selection II.9 (Girard).

- ↑ The narrative by Latifi of the life of the celebrated Iranian astronomer in 'The Ladder of the Sky' , in Persian, Āftāb, Sunday, 28 December 2008, .

- ↑ IRIB to spice up Ramadan evenings with special series, Tehran Times, 22 August 2009, .

- ↑ The name Nardebām-e Āsmān coincides with the Persian translation of the title Soll'am-os-Samā' (سُلّمُ السَماء) of a scientific work by Jamshid Kashani written in Arabic. In this work, which is also known as Resāleh-ye Kamālieh (رسالهٌ كماليه), Jamshid Kashani discusses such matters as the diameters of Earth, the Sun, the Moon, and of the stars, as well as the distances of these to Earth. He completed this work on 1 March 1407 CE in Kashan.

- ↑ The programmes of the Holy month of Ramadan, Channel 1, in Persian, 19 August 2009, . Here the name "Latifi" is incorrectly written as "Seifi".

- ↑ Dr Velāyati: 'The Ladder of the Sky' is faithful to history, in Persian, Āftāb, Tuesday, 1 September 2009, .

- ↑ Fatemeh Udbashi, Latifi's narrative of the life of the renowned Persian astronomer in 'The Ladder of the Sky' , in Persian, Mehr News Agency, 29 December 2008, .

See also

References

- Kennedy, Edward S. (1947), "Al-Kashi's Plate of Conjunctions", Isis 38 (1–2): 56–59, doi:10.1086/348036

- Kennedy, Edward S. (1950), "A Fifteenth-Century Planetary Computer: al-Kashi's "Tabaq al-Manateq" I. Motion of the Sun and Moon in Longitude", Isis 41 (2): 180–183, doi:10.1086/349146

- Kennedy, Edward S. (1951), "An Islamic Computer for Planetary Latitudes", Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 71 (1): 13–21, doi:10.2307/595221, JSTOR 595221

- Kennedy, Edward S. (1952), "A Fifteenth-Century Planetary Computer: al-Kashi's "Tabaq al-Maneteq" II: Longitudes, Distances, and Equations of the Planets", Isis 43 (1): 42–50, doi:10.1086/349363

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ghiyath al-Din Jamshid Mas'ud al-Kashi", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

External links

- Schmidl, Petra G. (2007). "Kāshī: Ghiyāth (al‐Milla wa‐) al‐Dīn Jamshīd ibn Masʿūd ibn Maḥmūd al‐Kāshī [al‐Kāshānī]". In Thomas Hockey; et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 613–5. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- A summary of "Miftah al-Hisab"

- About Jamshid Kashani

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|