Gettysburg Campaign

| Gettysburg Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Opposing commanders George G. Meade and Robert E. Lee | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Joseph Hooker George G. Meade (from June 28) | Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Potomac | Army of Northern Virginia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 90,000[1] | 75,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 30,100[3] | 27,000[4] | ||||||

The Gettysburg Campaign was a series of battles fought in June and July 1863, during the American Civil War. After his victory in the Battle of Chancellorsville, Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia moved north for offensive operations in Maryland and Pennsylvania, his second invasion of the North. The Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker and then (from June 28) by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, pursued Lee, defeated him at the Battle of Gettysburg, but allowed him to escape back to Virginia.

Lee's army slipped away from Federal contact at Fredericksburg, Virginia, on June 3, 1863. While they paused at Culpeper, the largest predominantly cavalry battle of the war was fought at Brandy Station on June 9. The Confederates crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains and moved north through the Shenandoah Valley, capturing the Union garrison at Winchester, Virginia, in the Second Battle of Winchester, June 13–15. Crossing the Potomac River, Lee's Second Corps advanced through Maryland and Pennsylvania, reaching the Susquehanna River and threatening the state capital of Harrisburg. However, the Army of the Potomac was in pursuit and had reached Frederick, Maryland, before Lee realized his opponent had crossed the Potomac. Lee moved swiftly to concentrate his army around the crossroads town of Gettysburg.

The Battle of Gettysburg was the largest of the war. Starting as a chance meeting engagement on July 1, the Confederates were initially successful in driving Union cavalry and two infantry corps from their defensive positions, through the town, and onto Cemetery Hill. On July 2, with most of both armies now present, Lee launched fierce assaults on both flanks of the Union defensive line, which were repulsed with heavy losses on both sides. On July 3, Lee focused his attention on the Union center. The defeat of his massive infantry assault, Pickett's Charge, caused Lee to order a retreat that began the evening of July 4.

The Confederate retreat to Virginia was plagued by bad weather, difficult roads, and numerous skirmishes with Union cavalry. However, Meade's army did not maneuver aggressively enough to prevent the Army of Northern Virginia from crossing the Potomac to safety on the night of July 13–14.

Background

Shortly after Lee's Army of Northern Virginia defeated Hooker's Army of the Potomac during the Chancellorsville Campaign (April 30 – May 6, 1863), Lee decided upon a second invasion of the North. Such a move would upset Union plans for the summer campaigning season, give Lee the ability to maneuver his army away from its defensive positions behind the Rappahannock River, and allow the Confederates to live off the bounty of the rich northern farms while giving war-ravaged Virginia a much needed rest. Lee's army could also threaten Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and encourage the growing peace movement in the North. Lee had written to his wife on April 19,

... next fall there will be a great change in public opinion at the North. The Republicans will be destroyed & I think the friends of peace will become so strong that the next administration will go in on that basis.[5]

The Confederate government wanted Lee to reduce Union pressure threatening their garrison at Vicksburg, Mississippi, but he declined their suggestions to send troops to provide direct aid, arguing for the value of a concentrated blow in the Northeast.[6]

In essence, Lee's strategy was identical to the one he employed in the Maryland Campaign of 1862. He had discovered only recently the secret of how Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan had defeated that invasion, by intercepting Lee's famous lost order to his corps commanders, which compelled him to fight in the Battle of Antietam before he could fully concentrate his army. This revelation improved his confidence that he could succeed in a northern invasion against another man he considered a timid and ineffective general, Joseph Hooker. Furthermore, after Chancellorsville he had supreme confidence in the men of his army, assuming they could handle any challenge he gave them.[7]

Opposing forces

Campaign timeline

The battles of the Gettysburg Campaign were fought in the following sequence; they are described in the context of logical, sometimes overlapping divisions of the campaign.

| Action | Dates | Section of campaign |

|---|---|---|

| Battle of Brandy Station | June 9, 1863 | Brandy Station |

| Second Battle of Winchester | June 13–15 | Winchester |

| Battle of Aldie | June 17 | Hooker's pursuit |

| Battle of Middleburg | June 17–19 | Hooker's pursuit |

| Battle of Upperville | June 21 | Hooker's pursuit |

| Battle of Fairfax Court House | June 27 | Stuart's ride |

| Skirmish of Sporting Hill | June 30 | Invasion of Pennsylvania |

| Battle of Hanover | June 30 | Stuart's ride |

| Battle of Gettysburg | July 1–3 | Gettysburg |

| Battle of Carlisle | July 1 | Stuart's ride |

| Battle of Hunterstown | July 2 | Stuart's ride |

| Battle of Fairfield | July 3 | Retreat |

| Battle of Monterey Pass | July 4–5 | Retreat |

| Battle of Williamsport | July 6–16 | Retreat |

| Battle of Boonsboro | July 8 | Retreat |

| Battle of Funkstown | July 10 | Retreat |

| Battle of Manassas Gap | July 23 | Retreat |

Lee's advance to Gettysburg

On June 3, 1863, Lee's army began to slip away northwesterly from Fredericksburg, Virginia, leaving A.P. Hill's Corps in fortifications above Fredericksburg to protect the Confederate rear as it withdrew. By June 5, Longstreet's and Ewell's corps were camped in and around Culpeper,[8] and Hooker had caught wind of the Confederate movement. Accordingly, he ordered Sedgwick to conduct a reconnaissance in force across the Rappahannock River to Hill's line, which resulted in a skirmish that convinced him Lee still occupied his old line around Fredericksburg. As a precaution, Lee temporarily halted Ewell's Corps, but when he saw that Hooker would not press the Fredericksburg line to bring on a battle, he ordered Ewell to continue. On June 9, Lee ordered Stuart to cross the Rappahannock and raid Union forward positions, screening the Confederate Army from observation or interference as it moved north. Anticipating this imminent offensive action, Stuart ordered his troopers into bivouac around Brandy Station.[9]

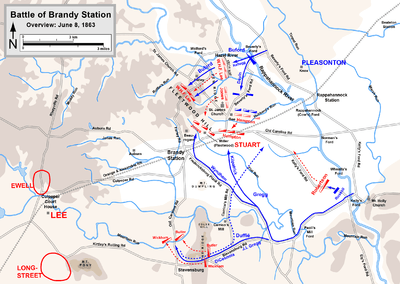

Brandy Station

Hooker interpreted Stuart's presence around Culpeper to be indicative of preparations for a raid on his army's supply lines. In reaction to this, he ordered Alfred Pleasonton's combined arms force of 8,000 cavalrymen and 3,000 infantry on a "spoiling raid,"[10] to "disperse and destroy" the 9,500 Confederates.[11] Pleasonton's attack plan called for a double envelopment of the enemy. The wing under John Buford would cross the river at Beverly's Ford, two miles (3 km) northeast of Brandy Station; at the same time, David McM. Gregg's wing would cross at Kelly's Ford, six miles (10 km) downstream to the southeast. However, Pleasonton was unaware of the precise disposition of the enemy and he incorrectly assumed that his force was substantially larger than the Confederates he faced.[12]

About 4:30 a.m. on June 9, Buford's column crossed the Rappahannock River in a dense fog, surprising Grumble Jones's brigade, which rode to the scene partially dressed and often riding bareback. They struck Buford's leading brigade and temporarily checked its progress, just short of where Stuart's Horse Artillery was camped and was vulnerable to capture. The artillery unlimbered on two knolls on either side of the Beverly's Ford Road. Most of Jones's command rallied to the left of this Confederate artillery line, while Hampton's brigade formed to the right. The 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry unsuccessfully charged the guns at St. James Church, suffering the greatest casualties of any regiment in the battle.[13]

Buford tried to turn the Confederate left and dislodge the artillery that was blocking the direct route to Brandy Station and sustained heavy losses displacing Rooney Lee's brigade from a stone wall on Yew Ridge. Then, to the amazement of Buford's men, the Confederates began pulling back. They were reacting to the arrival of Gregg's cavalry division of about 2,800 men, which was the second major surprise of the day. Although Gregg had intended to cross at Kelly's Ford at dawn, in concert with Buford's crossing at Beverly's, his men were delayed two hours. Between Gregg and the St. James battle was a prominent ridge called Fleetwood Hill, which had been Stuart's headquarters the previous night. Stuart and most of his staff had departed for the front by this time, but a few shots from a 6-pounder howitzer delayed the advance of Col. Percy Wyndham's brigade as they sent out skirmishers and returned cannon fire. When Gregg's men charged up the western slope of Fleetwood and neared the crest, the lead elements of Jones's brigade, which had just withdrawn from St. James Church, rode over the crown.[14]

Gregg's next brigade, led by Col. Judson Kilpatrick, swung around east of Brandy Station and attacked up the southern end and the eastern slope of Fleetwood Hill, only to discover that their appearance coincided with the arrival of Hampton's brigade. A series of confusing charges and countercharges swept back and forth across the hill. The Confederates finally cleared the hill. Col. Alfred N. Duffié's small 1,200-man division was delayed by two Confederate regiments in the vicinity of Stevensburg and arrived on the field too late to affect the action. While Jones and Hampton withdrew from their initial positions to fight at Fleetwood Hill, Rooney Lee continued to confront Buford, falling back to the northern end of the hill. Reinforced by Fitzhugh Lee's brigade, Rooney Lee launched a counterattack against Buford at the same time as Pleasonton had called for a general withdrawal near sunset, and the ten-hour battle was over.[15]

Brandy Station was the largest predominantly cavalry fight of the war, and the largest to take place on American soil.[16] It was a tactical draw, although Pleasonton withdrew before finding the location of Lee's infantry nearby and Stuart claimed a victory, attempting to disguise the embarrassment of a cavalry force being surprised as it was by Pleasonton. The battle established the emerging reputation of the Union cavalry as a peer of the Confederate mounted arm.[17]

Winchester

After Brandy Station, Lee's infantry forces began crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains and headed north, "down" the Shenandoah Valley. Ewell's Corps, in the lead, crossed at Chester Gap on June 12 and then through Front Royal toward Winchester, Virginia. Longstreet's Corps (accompanied by General Lee) moved to protect Ashby's Gap and Snicker's Gap. A.P. Hill waited until Hooker had withdrawn from Fredericksburg on June 14 and then followed Ewell's route across the mountains, leapfrogging Longstreet's Corps, which then brought up the rear of the army. Stuart's cavalry remained to the east of the Blue Ridge to screen Lee's army.[18]

The Union garrison at Winchester stood directly in Ewell's path. It was commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy, who had 7,000 men in three brigades—two in Winchester and one 10 miles to the east at Berryville. Three forts with interconnecting trenches had been constructed to defend the town. General-in-chief Henry W. Halleck had since May ordered Milroy's superior, Maj. Gen. Robert C. Schenck of the Middle Department, to withdraw Milroy's men to Harpers Ferry, but Schenck believed that these were only instances of Halleck's typical suggestions rather than direct orders and did not act on them until explicitly threatened with removal on June 14. By then it was too late. As Allegheny Johnson's division approached Winchester from the south on June 14 and Jubal Early approached from the west, Ewell ordered Rodes's division to Berryville and then to Martinsburg, north of Winchester. These movements effectively surrounded the Federal garrison.[19]

At 6 p.m. on June 14, Confederate artillery opened fire on the Union's West Fort and the brigade of Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays led the charge that captured the fort and a Union battery. As darkness fell, Milroy belatedly decided to retreat from his two remaining forts. Anticipating the movement, Ewell ordered Johnson to march northwest and block the Union escape route. At 3:30 a.m. on June 15, Johnson's column intercepted Milroy's on the Charles Town Road. Although Milroy ordered his men to fight their way out of the situation, when the Stonewall Brigade arrived just after dawn to cut the turnpike to the north, Milroy's men began to surrender in large numbers. Milroy escaped personally but the Second Battle of Winchester cost the Union about 4,450 casualties (4,000 captured) out of 7,000 engaged, while the Confederates lost only 250 of 12,500 engaged.[20]

Ewell began crossing the Potomac River near Hagerstown, Maryland, late on June 15, along with Jenkins's cavalry brigade. Hill's and Longstreet's corps followed on June 24 and June 25.[21]

Hooker's pursuit

"Fighting Joe" Hooker did not know Lee's intentions, and Stuart's cavalry masked the Confederate army's movements behind the Blue Ridge effectively. He initially conceived the idea of reacting to Lee's absence by seizing unprotected Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. But President Abraham Lincoln sternly reminded him that Lee's army was the true objective. His orders were to pursue and defeat Lee but to stay between Lee and Washington and Baltimore. On June 14, the Army of the Potomac departed Fredericksburg and reached Manassas Junction on June 16. Hooker dispatched Pleasonton's cavalry again to punch through the Confederate cavalry screen to find the main Confederate army, which led to three minor cavalry battles from June 17 through June 21 in the Loudoun Valley.[22]

Pleasonton ordered David McM. Gregg's division from Manassas Junction westward down the Little River Turnpike to Aldie. Aldie was tactically important in that near the village the Little River Turnpike intersected both of the turnpikes leading through Ashby's Gap and Snickers Gap into the Valley. The Confederate cavalry brigade of Col. Thomas T. Munford was entering Aldie from the west, preparing to bivouac, when three brigades of Gregg's division entered from the east at about 4 p.m. on June 17, surprising both sides. The resulting Battle of Aldie was a fierce mounted fight of four hours with about 250 total casualties. Munford withdrew toward Middleburg.[23]

While the fighting occurred at Aldie, the Union cavalry brigade of Col. Alfred N. Duffié arrived south of Middleburg in the late afternoon and drove in the Confederate pickets. Stuart was in the town at the time and managed to escape before his brigades under Munford and Beverly Robertson routed Duffié in an early morning assault on June 18. The primary action of the Battle of Middleburg occurred on the morning of June 19 when Col. J. Irvin Gregg's brigade advanced west from Aldie and attacked Stuart's line on a ridge west of Middleburg. Stuart repulsed Gregg's charge, counterattacked, then fell back to defensive positions a half-mile to the west.[24]

On June 21, Pleasonton again attempted to break Stuart's screen by advancing on Upperville, 9 miles to the west of Middleburg. The cavalry brigades of Irvin Gregg and Judson Kilpatrick were accompanied by infantry from Col. Strong Vincent's brigade on the Ashby's Gap Turnpike. Buford's cavalry division moved northwest against Stuart's left flank, but made little progress against Grumble Jones's and John R. Chambliss's brigades. The Battle of Upperville ended as Stuart conducted a fierce fighting withdrawal and took up a strong defensive position in Ashby's Gap.[25]

After successfully defending his screen for almost a week, Stuart found himself motivated to begin the most controversial adventure of his career, Stuart's raid around the eastern flank of the Union Army.[26]

Hooker's significant pursuit with the bulk of his army began on June 25, after he learned that the Army of Northern Virginia had crossed the Potomac River. He ordered the Army of the Potomac to cross into Maryland and concentrate at Middletown (Slocum's XII Corps) and Frederick (the rest of the army, led by Reynolds's advance wing—the I, III, and XI Corps).[27]

The invasion of Pennsylvania

President Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 100,000 volunteers from four states to serve a term of six months "to repel the threatened and imminent invasion of Pennsylvania."[28] Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin called for 50,000 volunteers to take arms as volunteer militia; only 7,000 initially responded, and Curtin asked for help from the New York State Militia. Gov. Joel Parker of New Jersey also responded by sending troops to Pennsylvania. The War Department created the Department of the Susquehanna, commanded by Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch, to coordinate defensive efforts in Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Philadelphia were considered potential targets and defensive preparations were made. In Harrisburg, the state government removed its archives from the town for safekeeping. (In much of southern Pennsylvania, the Gettysburg campaign became widely known as the "Emergency of 1863." The military campaign resulted in the displacement of thousands of refugees from Maryland and Pennsylvania who fled northward and eastward to avoid the oncoming Confederates, and resulted in a shift in demographics in several southern Pennsylvania boroughs and counties.)[29]

Although a primary purpose of the campaign was for the Army of Northern Virginia to accumulate food and supplies outside of Virginia, Lee gave strict orders (General Order 72) to his army to minimize any negative impacts on the civilian population.[30] Food, horses, and other supplies were generally not seized outright, although quartermasters reimbursing Northern farmers and merchants using Confederate money were not well received. Various towns, most notably York, Pennsylvania, were required to pay indemnities in lieu of supplies, under threat of destruction. During the invasion, the Confederates seized some 40 northern African Americans, a few of whom were escaped fugitive slaves but most were freemen. They were sent south under guard into slavery.[31]

Ewell's corps continued to push deeper into Pennsylvania, with two divisions heading through the Cumberland Valley to threaten Harrisburg, while Jubal Early's division of Ewell's Corps marched eastward over the South Mountain range, occupying Gettysburg on June 26 after a brief series of skirmishes with state emergency militia and two companies of cavalry. Early laid the borough under tribute but did not collect any significant quantities of supplies. Soldiers burned several railroad cars and a covered bridge, and they destroyed nearby rails and telegraph lines. The following morning, Early departed for adjacent York County.[32]

The brigade of Brig. Gen. John B. Gordon of Early's division reached the Susquehanna on June 28, where militia guarded the 5,629-foot-long covered bridge at Wrightsville. Gordon's artillery fire caused the well fortified militiamen to retreat and burn the bridge. Confederate cavalry under the command of Brig. Gen. Albert G. Jenkins raided nearby Mechanicsburg on June 28 and skirmished with militia at Sporting Hill on the west side of Camp Hill on June 29. The Confederates then pressed on to the outer defenses of Fort Couch, where they skirmished with the outer picket line for over an hour, the northernmost engagement of the Gettysburg Campaign. They later withdrew in the direction of Carlisle.[33]

Stuart's ride

Jeb Stuart enjoyed the glory of circumnavigating an enemy army, which he had done on two previous occasions in 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign and at the end of the Maryland Campaign. It is possible that he had the same intention when he spoke to Robert E. Lee following the Battle of Upperville. He certainly needed to erase the stain on his reputation represented by his surprise and near defeat at the Battle of Brandy Station. The exact nature of Lee's order to Stuart on June 22 has been argued by the participants and historians ever since, but the essence was that he was instructed to guard the mountain passes with part of his force while the Army of Northern Virginia was still south of the Potomac and that he was to cross the river with the remainder of the army and screen the right flank of Ewell's Second Corps. Instead of taking a direct route north near the Blue Ridge Mountains, however, Stuart chose to reach Ewell's flank by taking his three best brigades (those of Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee, and John R. Chambliss, the latter replacing the wounded W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee) between the Union army and Washington, moving north through Rockville to Westminster and on into Pennsylvania, hoping to capture supplies along the way and cause havoc near the enemy capital. Stuart and his three brigades departed Salem Depot at 1 a.m. on June 25.[34]

Unfortunately for Stuart's plan, the Union army's movement was underway and his proposed route was blocked by columns of Federal infantry from Hancock's II Corps, forcing him to veer farther to the east than either he or General Lee had anticipated. This prevented Stuart from linking up with Ewell as ordered and deprived Lee of the use of his prime cavalry force, the "eyes and ears" of the army, while advancing into unfamiliar enemy territory.[35]

Stuart's command reached Fairfax Court House, where they were delayed for half a day by the small but spirited Battle of Fairfax Court House (June 1863) on June 27, and crossed the Potomac River at Rowser's Ford at 3 a.m. on June 28. Upon entering Maryland, the cavalrymen attacked the C & O Canal, one of the major supply lines for the Army of the Potomac, capturing canal boats and cargo. They entered Rockville on June 28, also a key wagon supply road between the Union Army and Washington, tearing down miles of telegraph wire and capturing a wagon train of 140 brand new, fully loaded wagons and mule teams. This wagon train would prove to be a logistical hindrance to Stuart's advance, but he interpreted Lee's orders as placing importance on gathering supplies. The proximity of the Confederate raiders provoked some consternation in the national capital and Meade dispatched two cavalry brigades and an artillery battery to pursue the Confederates. Stuart supposedly told one of his prisoners from the wagon train that were it not for his fatigued horses "he would have marched down the 7th Street Road [and] took Abe & Cabinet prisoners."[36]

Stuart had planned to reach Hanover, Pennsylvania, by the morning of June 28, but rode into Westminster, Maryland, instead late on the afternoon of June 29. Here his men clashed briefly with and overwhelmed two companies of the 1st Delaware Cavalry under Maj. Napoleon B. Knight, chasing them a long distance on the Baltimore road, which Stuart claimed caused a "great panic" in the city of Baltimore.[37]

Meanwhile, Union cavalry commander Alfred Pleasonton ordered his divisions to spread out in their movement north with the army, looking for Confederates. Judson Kilpatrick's division was on the right flank of the advance and passed through Hanover on the morning of June 30. The head of Stuart's column encountered Kilpatrick's rear as it passed through town and scattered it. The Battle of Hanover ended after Kilpatrick's men regrouped and drove the Confederates out of town. Stuart's brigades had been better positioned to guard their captured wagon train than to take advantage of the encounter with Kilpatrick. To protect his wagons and prisoners, he delayed until nightfall and then detoured around Hanover by way of Jefferson to the east, increasing his march by 5 miles. After a 20-mile trek in the dark, his exhausted men reached Dover on the morning of July 1, the same time that his Confederate infantry colleagues began to fight Union cavalrymen under John Buford at Gettysburg.[38]

Leaving Hampton's Brigade and the wagon train at Dillsburg, Stuart headed for Carlisle, hoping to find Ewell. Instead, he found nearly 3,000 Pennsylvania and New York militia occupying the borough. After lobbing a few shells into town during the early evening of July 1 and burning the Carlisle Barracks, Stuart concluded the so-called Battle of Carlisle and withdrew after midnight to the south towards Gettysburg. The fighting at Hanover, the long march through York County with the captured wagons, and the brief encounter at Carlisle slowed Stuart considerably in his attempt to rejoin the main army.[39]

Stuart and the bulk of his command reached Lee at Gettysburg the afternoon of July 2. He ordered Wade Hampton to take a position to cover the left rear of the Confederate battle lines. Hampton moved into position astride the Hunterstown Road four miles (6 km) northeast of town, blocking access for any Union forces that might try to swing around behind Lee's lines. Two brigades of Union cavalry from Judson Kilpatrick's division under Brig. Gens. George Armstrong Custer and Elon J. Farnsworth were probing for the end of the Confederate left flank. Custer attacked Hampton in the Battle of Hunterstown on the road between Hunterstown and Gettysburg, and Hampton counterattacked. When Farnsworth arrived with his brigade, Hampton did not press his attack, and an artillery duel ensued until dark. Hampton then withdrew towards Gettysburg to rejoin Stuart.[40]

Dix's advance against Richmond

As Lee's offensive strategy became clear, Union general-in-chief Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck planned a countermove that could take advantage of the now lightly defended Confederate capital of Richmond. He ordered the Union Department of Virginia, two corps under Maj. Gen. John A. Dix, to move on Richmond from its locations on the Virginia Peninsula (around Yorktown and Williamsburg) and near Suffolk. However, Halleck made the mistake of not explicitly ordering Dix to attack Richmond. The orders were to "threaten Richmond, by seizing and destroying their railroad bridges over the South and North Anna Rivers, and do them all the damage possible." Dix, a well-respected politician, was not an aggressive general, but he eventually contemplated attacking Richmond despite the vagueness of Halleck's instructions. On June 27, his men conducted a successful cavalry raid on Hanover Junction, led by Col. Samuel P. Spear, which defeated the Confederate regiment guarding the railroad junction, destroyed the bridge over the South Anna River and the quartermaster's depot, capturing supplies, wagons, and 100 prisoners including General Lee's son, Brig. Gen. W. H. F. "Rooney" Lee. On June 29, at a council of war, Dix and his lieutenants expressed concerns about their limited strength (about 32,000 men) and decided to limit themselves to threatening gestures. Confederate Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill wrote that the Union advance on Richmond was "not a feint but a faint." The net effect of the operation was primarily psychological, causing the Confederates to hold back some troops from Lee's offensive to guard the capital.[41]

Meade assumes command

On the evening of June 27, Lincoln sent orders relieving Hooker. Hooker had argued with Halleck about defending the garrison at Harpers Ferry and petulantly offered to resign, which Halleck and Lincoln promptly accepted. George Meade, a Pennsylvanian who was commanding the V Corps, was ordered to assume command of the Army of the Potomac early on the morning of June 28 in Frederick, Maryland. Meade was surprised by the change of command order, having previously expressed his lack of interest in the army command. In fact, when an officer from Washington woke him with the order, he assumed he was being arrested for some transgression. Despite having little knowledge of what Hooker's plans had been or the exact locations of the three columns moving quickly to the northwest, Meade kept up the pace. He telegraphed to Halleck, in accepting his new command, that he would "Move toward the Susquehanna, keeping Washington and Baltimore well covered, and if the enemy is checked in his attempt to cross the Susquehanna or if he turns toward Baltimore, to give him battle."[42]

On June 30, Meade's headquarters advanced to Taneytown, Maryland, and he issued two important orders. The first directed that a general advance in the direction of Gettysburg begin on July 1, a destination that was from 5 to 25 miles away from each of his seven infantry corps. The second order, known as the Pipe Creek Circular, established a prospective line on Big Pipe Creek, which had been surveyed by his engineers as a strong defensive position. Meade had the option of occupying this position and hoping that Lee would attack him there; alternatively, it would represent a fall back position if the army got into trouble at Gettysburg.[43]

Lee concentrates his army

The lack of Stuart's cavalry intelligence kept Lee unaware that his army's normally sluggish foe had moved as far north as it had. It was only after a spy hired by Longstreet reported in that Lee found out his opponent had crossed the Potomac and was following him nearby. By June 29, Lee's army was strung out in an arc from Chambersburg (28 miles (45 km) northwest of Gettysburg) to Carlisle (30 miles (48 km) north of Gettysburg) to near Harrisburg and Wrightsville on the Susquehanna River. Ewell's Corps had almost reached the Susquehanna River and was prepared to menace Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania state capital. Early's Division occupied York, which was the largest Northern town to fall to the Confederates during the war. Longstreet and Hill were near Chambersburg.[44]

Lee ordered a concentration of his forces around Cashtown, located at the eastern base of South Mountain and 8 miles (13 km) west of Gettysburg.[45] On June 30, while part of Hill's Corps was in Cashtown, one of Hill's brigades, North Carolinians under Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, ventured toward Gettysburg. The memoirs of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth, Pettigrew's division commander, claimed that he sent Pettigrew to search for supplies in town—especially shoes.[46]

When Pettigrew's troops approached Gettysburg on June 30, they noticed Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. John Buford arriving south of town, and Pettigrew returned to Cashtown without engaging them. When Pettigrew told Hill and Heth about what he had seen, neither general believed that there was a substantial Federal force in or near the town, suspecting that it had been only Pennsylvania militia. Despite General Lee's order to avoid a general engagement until his entire army was concentrated, Hill decided to mount a significant reconnaissance in force the following morning to determine the size and strength of the enemy force in his front. Around 5 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, two brigades of Heth's division advanced to Gettysburg.[47]

Battle of Gettysburg

The two armies began to collide at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. The first day proceeded in three phases as combatants continued to arrive at the battlefield. In the morning, two brigades of Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division (of Hill's Third Corps) were delayed by dismounted Union cavalrymen under Brig. Gen. John Buford. As infantry reinforcements arrived under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds from the I Corps, the Confederate assaults down the Chambersburg Pike were repulsed, although Gen. Reynolds was killed. By early afternoon, the Union XI Corps had arrived, and the Union position was in a semicircle from west to north of the town. Ewell's Second Corps began a massive assault from the north, with Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes's division attacking from Oak Hill and Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early's division attacking across the open fields north of town. The Union lines generally held under extremely heavy pressure, although the salient at Barlow's Knoll was overrun. The third phase of the battle came as Rodes renewed his assault from the north and Heth returned with his entire division from the west, accompanied by the division of Maj. Gen. W. Dorsey Pender. Heavy fighting in Herbst's Woods (near the Lutheran Theological Seminary) and on Oak Ridge finally caused the Union line to collapse. Some of the Federals conducted a fighting withdrawal through the town, suffering heavy casualties and losing many prisoners; others simply retreated. They took up good defensive positions on Cemetery Hill and waited for additional attacks. Despite discretionary orders from Robert E. Lee to take the heights "if practicable," Richard Ewell chose not to attack. Historians have debated ever since how the battle might have ended differently if he had found it practicable to do so.[48]

On the second day, Lee attempted to capitalize on his first day's success by launching multiple attacks against the Union flanks. After a lengthy delay to assemble his forces and avoid detection in his approach march, Longstreet attacked with his First Corps against the Union left flank. His division under Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood attacked Little Round Top and Devil's Den. To Hood's left, Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws attacked the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard. Although neither prevailed, the Union III Corps was effectively destroyed as a combat organization as it attempted to defend a salient over too wide a front. Gen. Meade rushed as many as 20,000 reinforcements from elsewhere in his line to resist these fierce assaults. The attacks in this sector concluded with an unsuccessful assault by the Third Corps division of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson against the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. That evening, Ewell's Second Corps turned demonstrations against the Union right flank into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and East Cemetery Hill, but both were repulsed. The Union army had occupied strong defensive positions, and Meade handled his forces well, resulting in heavy losses for both sides but leaving the disposition of forces on both sides essentially unchanged.[49]

After attacks on both Union flanks had failed the day and night before, Lee was determined to strike the Union center on the third day. He decided to support this attack with a renewed thrust on the Union right that was supposed to start in concert with his assault on the center. However, the fighting on Culp's Hill resumed early in the morning with a Union counterattack, hours before Longstreet could begin his attack on the center. The Union troops on fortified Culp's Hill had been reinforced and the Confederates made no progress after multiple, futile assaults that lasted until noon. The infantry assault on Cemetery Ridge known as Pickett's Charge was preceded by a massive artillery bombardment at 1 p.m. that was meant to soften up the Union defense and silence its artillery, but it was largely ineffective. Approximately 12,500 men in nine infantry brigades advanced over open fields for three quarters of a mile under heavy Union artillery and rifle fire. Although some Confederates were able to breach the low stone wall that shielded many of the Union defenders, they could not maintain their hold and were repulsed with over 50% casualties.[50]

During and after Pickett's Charge on the third day, two significant cavalry battles also occurred: one approximately three miles (5 km) to the east, in the area known today as East Cavalry Field, the other southwest of the [Big] Round Top mountain (sometimes called South Cavalry Field). The East Cavalry Field fighting was an attempt by Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's Confederate cavalry to get into the Federal rear and exploit any success that Pickett's Charge may have generated. Union cavalry under Brig. Gens. David McM. Gregg and George Armstrong Custer repulsed the Confederate advances. In South Cavalry Field, after Pickett's Charge had been defeated, reckless cavalry charges against the right flank of the Confederate Army, ordered by Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, were easily repulsed.[51]

The three-day battle in and around Gettysburg resulted in the largest number of casualties in the American Civil War—between 46,000 and 51,000.[52] In conjunction with the Union victory at Vicksburg on July 4, Gettysburg is frequently cited as the war's turning point.[53]

Lee's retreat to Virginia

Following Pickett's Charge, the Confederates returned to their positions on Seminary Ridge and prepared fortifications to receive a counterattack. When the Union attack had not occurred by the evening of July 4, Lee realized that he could accomplish nothing more in his campaign and that he had to return his battered army to Virginia. Lee started his Army of Northern Virginia in motion late the evening of July 4 towards Fairfield and Chambersburg. Cavalry under Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden was entrusted to escort the miles-long wagon train of supplies and wounded men that Lee wanted to take back to Virginia with him, using the route through Cashtown and Hagerstown to Williamsport, Maryland. Thousands of more seriously wounded soldiers were left behind in the Gettysburg area, along with medical personnel. However, despite casualties of over 20,000 men, including a number of senior officers, the morale of Lee's army remained high and their respect for the commanding general was not diminished by their reverses.[54]

Unfortunately for the Confederate Army, however, once they reached the Potomac they would find it difficult to cross. Torrential rains that started on July 4 flooded the river at Williamsport, making fording impossible. Four miles downstream at Falling Waters, Union cavalry destroyed Lee's lightly guarded pontoon bridge on July 4. The only way to cross the river was a small ferry at Williamsport. The Confederates could potentially be trapped, forced to defend themselves against Meade with their backs to the river.[55]

The route of the bulk of Lee's army was through Fairfield and over Monterey Pass to Hagerstown. A small but important action that occurred while Pickett's Charge was still underway, the Battle of Fairfield, prevented the Union from blocking this route. Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt's brigade departed from Emmitsburg with orders to strike the Confederate left and rear along Seminary Ridge. Merritt dispatched about 400 men from the 6th U.S. Cavalry to seize foraging wagons that had been reported in the area. Before they were able to reach the wagons, the 7th Virginia Cavalry, leading a column under Confederate Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones, intercepted the regulars, but the U.S. cavalrymen repulsed the Virginians. Jones sent in the 6th Virginia Cavalry, which successfully charged and swarmed over the Union troopers. There were 242 Union casualties, primarily prisoners, and 44 casualties among the Confederates.[56]

Imboden's journey was one of extreme misery, conducted during the torrential rains that began on July 4, in which the 8,000 wounded men were forced to endure the weather and the rough roads in wagons without suspensions. The train was harassed throughout its march. At dawn on July 5, civilians in Greencastle ambushed the train with axes, attacking the wheels of the wagons, until they were driven off. That afternoon at Cunningham's Cross Roads, Union cavalry attacked the column, capturing 134 wagons, 600 horses and mules, and 645 prisoners, about half of whom were wounded. These losses so angered Stuart that he demanded a court of inquiry to investigate.[57]

Early on July 4 Meade sent his cavalry to strike the enemy's rear and lines of communication so as to "harass and annoy him as much as possible in his retreat." Eight of nine cavalry brigades (except Col. John B. McIntosh's of Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's division) took to the field. Col. J. Irvin Gregg's brigade (of his cousin David Gregg's division) moved toward Cashtown via Hunterstown and the Mummasburg Road, but all of the others moved south of Gettysburg. Brig. Gen. John Buford's division went directly from Westminster to Frederick, where they were joined by Merritt's division on the night of July 5.[58]

Late on July 4, Meade held a council of war in which his corps commanders agreed that the army should remain at Gettysburg until Lee acted, and that the cavalry should pursue Lee in any retreat. Meade decided to have Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren take a division from Sedgwick's VI Corps to probe the Confederate line and determine Lee's intentions. By the morning of July 5, Meade learned of Lee's departure, but he hesitated to order a general pursuit until he had received the results of Warren's reconnaissance.[59]

The Battle of Monterey Pass began as Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick's cavalry division easily brushed aside Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson's pickets and encountered a detachment of 20 men from the Confederate 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, under Capt. G. M. Emack, that was guarding the road to Monterey Pass. Aided by a detachment of the 4th North Carolina Cavalry and a single cannon, the Marylanders delayed the advance of 4,500 Union cavalrymen until well after midnight. Kilpatrick ordered Brig. Gen. George A. Custer to charge the Confederates with the 6th Michigan Cavalry, which broke the deadlock and allowed Kilpatrick's men to reach and attack the wagon train. They captured or destroyed numerous wagons and captured 1,360 prisoners—primarily wounded men in ambulances—and a large number of horses and mules.[60]

As Meade's infantry began to march in earnest in pursuit of Lee on the morning of July 7, Buford's division departed from Frederick to destroy Imboden's train before it could cross the Potomac. At 5 p.m. on July 7 his men reached within a half-mile of the parked trains, but Imboden's command repulsed their advance. Buford heard Kilpatrick's artillery in the vicinity and requested support on his right. Kilpatrick's men had moved toward Hagerstown and pushed out the two small brigades of Chambliss and Robertson. However, infantry commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson drove Kilpatrick's men through the streets of town. Stuart's remaining brigades came up and were reinforced by two brigades of Hood's Division and Hagerstown was recaptured by the Confederates. Kilpatrick chose to respond to Buford's request for assistance and join the attack on Imboden at Williamsport. Stuart's men pressured Kilpatrick's rear and right flank from their position at Hagerstown and Kilpatrick's men gave way and exposed Buford's rear to the attack. Buford gave up his effort when darkness fell.[61]

Lee's rear guard cavalry clashed with Federal cavalry in the South Mountain passes in the Battle of Boonsboro on July 8, delaying Union pursuit. In the Battle of Funkstown on July 10, Stuart's cavalry continued its efforts to delay Federal pursuit in an encounter near Funkstown, Maryland, which resulted in nearly 500 casualties on both sides. The fight also marked the first time since the Battle of Gettysburg that Union infantry engaged Confederate infantry in the same engagement. Stuart was successful in delaying Pleasonton's cavalry for another day.[62]

By July 9 most of the Army of the Potomac was concentrated in a 5-mile line from Rohrersville to Boonsboro. Other Union forces were in position to protect the outer flanks at Maryland Heights and at Waynesboro.[63] By July 11 the Confederates occupied a 6-mile, highly fortified line on high ground with their right resting on the Potomac River near Downsville and the left about 1.5 miles southwest of Hagerstown, covering the only road from there to Williamsport.[64]

Meade telegraphed to general-in-chief Henry W. Halleck on July 12 that he intended to attack the next day, "unless something intervenes to prevent it." He once again called a council of war with his subordinates on the night of July 12, which resulted in a postponement of an attack until reconnaissance of the Confederate position could be performed, which Meade conducted the next morning. By that time, Lee became frustrated waiting for Meade to attack him and was dismayed to see that the Federal troops were digging entrenchments of their own in front of his works. Confederate engineers had completed a new pontoon bridge over the Potomac, which had also subsided enough to be forded. Lee ordered a retreat to start after dark, with Longstreet's and Hill's corps and the artillery to use the pontoon bridge at Falling Waters and Ewell's corps to ford the river at Williamsport.[65]

On the morning of July 14, advancing Union skirmishers found that the entrenchments were empty. Cavalry under Buford and Kilpatrick attacked the rearguard of Lee's army, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division, which was still on a ridge about a mile and a half from Falling Waters. The initial attack caught the Confederates by surprise after a long night with little sleep, and hand-to-hand fighting ensued. Kilpatrick attacked again and Buford struck them in their right and rear. Heth's and Pender's divisions lost numerous prisoners. Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew, who had survived Pickett's Charge with a minor hand wound, was mortally wounded at Falling Waters. This minor success against Heth did not make up for the extreme frustration in the Lincoln administration about allowing Lee to escape. The president was quoted as saying, "We had them within our grasp. We had only to stretch forth our hands and they were ours. And nothing I could say or do could make the Army move."[66]

The two armies did not take up positions across from each other on the Rappahannock River for almost two weeks. On July 16 the cavalry brigades of Fitzhugh Lee and Chambliss held the fords on the Potomac at Shepherdstown to prevent crossing by the Federal infantry. The cavalry division under David Gregg approached the fords and the Confederates attacked them, but the Union cavalrymen held their position until dark before withdrawing.[67]

The Army of the Potomac crossed the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry and Berlin (now named Brunswick) on July 17–18. They advanced along the east side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, trying to interpose themselves between Lee's army and Richmond. On July 23, in the Battle of Manassas Gap, Meade ordered French's III Corps to cut off the retreating Confederate columns at Front Royal, by forcing passage through Manassas Gap. At first light, French began slowly pushing the Stonewall Brigade back into the gap. About 4:30 p.m., a strong Union attack drove the Confederates until they were reinforced by Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes's division and artillery. By dusk, the poorly coordinated Union attacks were abandoned. During the night, Confederate forces withdrew into the Luray Valley. On July 24, the Union army occupied Front Royal, but Lee's army was safely beyond pursuit.[68]

Aftermath

The Gettysburg Campaign represented the final major offensive by Robert E. Lee in the Civil War. Afterward, all combat operations of the Army of Northern Virginia were in reaction to Union initiatives. Lee suffered over 27,000 casualties during the campaign,[4] a price very difficult for the Confederacy to pay. The campaign met only some of its major objectives: it had disrupted Union plans for a summer campaign in Virginia, temporarily protecting the citizens and economy of that state, and it had allowed Lee's men to live off the bountiful Maryland and Pennsylvania countryside and plunder vast amounts of food and supplies that they carried back with them and that would allow them to continue the war. However, the myth of Lee's invincibility had been shattered and not a single Union soldier was removed from the Vicksburg Campaign to react to Lee's invasion of the North.[69] (Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, the day Lee ordered his retreat.) Union campaign casualties were approximately 30,100.[3]

Meade was severely criticized for allowing Lee to escape, just as Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan had been after the Battle of Antietam. Under pressure from Lincoln, he launched two campaigns in the fall of 1863—Bristoe and Mine Run—that attempted to defeat Lee. Both were failures. He also suffered humiliation at the hands of his political enemies in front of the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War, questioning his actions at Gettysburg and his failure to defeat Lee during the retreat to the Potomac.[70]

On November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln spoke at the dedication ceremonies for the national cemetery created at the Gettysburg battlefield. His Gettysburg Address redefined the war, calling for a "new birth of freedom" in the nation, which established the destruction of slavery as an implied goal.[71]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gettysburg campaign. |

Notes

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 502–503.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 503.

- 1 2 Sears, p. 496. Casualties outside of Gettysburg, including the large capture of Union troops at Winchester, were 7,300.

- 1 2 Sears, p. 498. In addition to Gettysburg itself, there were approximately 4,500 casualties on the march north and during the retreat.

- ↑ Sears, p. 15.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 5–7; Sears, p. 15.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Salmon, pp. 193–94; Loosbrock, p. 272.

- ↑ Salmon, p. 193; Sears, p. 60; Gottfried, p. 2; Mingus, p. 12.

- ↑ Salmon, p. 193.

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 204; NPS website.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 62–63; Sears, pp. 64–65; Gottfried, p. 6.

- ↑ NPS; Loosbrock, p. 272; Longacre, pp. 66–73; Kennedy, p. 204; Sears, pp. 65–67; Salmon, pp. 194, 198; Eicher, p. 492.

- ↑ NPS; Longacre, pp. 74–78; Sears, pp. 68–70; Gottfried, p. 6;Salmon, pp. 199–201.

- ↑ NPS; Longacre, pp. 78–85; Sears, pp. 71–72; Gottfried, p. 6; Kennedy, p. 204; Salmon, p. 202; Eicher, p. 492.

- ↑ Brandy Station Foundation. Of the 20,500 men engaged, approximately 3,000 were Union infantrymen. The Battle of Trevilian Station in 1864 was the largest all-cavalry battle of the war. According to the Civil War Preservation Trust Brandy Station was the largest battle of its kind on American soil.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 73–74; Longacre, pp. 87–90; Salmon, p. 203; Loosbrock, p. 274.

- ↑ Sears, p. 74; Salmon, p. 203.

- ↑ Salmon, pp. 204–205; Gottfried, pp. 44–47; Sears, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Gottfried, pp. 48–51; Sears, pp. 78–81; Salmon, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Trudeau, pp. 45, 66; Gottfried, p. 14.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 83–84; Longacre, p. 103; Gottfried, pp. 12–17; Salmon, pp. 196–97.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 104–110; Salmon, pp. 207–209; Gottfried, p. 18; Sears, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 111–12, 119–24; Gottfried, p. 18; Sears, p. 98; Salmon, pp. 210–11.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 125–32; Gottfried, p. 24; Sears, pp. 99–100; Salmon, pp. 212–13.

- ↑ Salmon, p. 197; Longacre, p. 101.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 124–25; Sears, p. 120; Gottfried, p. 28.

- ↑ Mingus, p. 27.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 91–92, 109–10; Mingus, pp. 17, 22, 29.

- ↑ Woodworth, p. 24.

- ↑ Symonds, pp. 49–54; Mingus, pp. 90, 204–207; Sears pp. 111–12.

- ↑ Nye, pp. 272–78; Mingus, pp. 126–95; Gottfried, p. 30; Sears, pp. 102, 113.

- ↑ Gottfried, pp. 34–36; Mingus, pp. 40, 324–83; Boyd, Neil, "The Confederate Invasion of Central Pennsylvania and the Battle of Sporting Hill".

- ↑ Sears, pp. 104–106; Longacre, pp. 148–52; Gottfried, p. 28; Eicher, p. 506; Coddington, p. 108.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 108–13; Longacre, pp. 152–53; Sears, p. 106; Gottfried, p. 28.

- ↑ Wittenberg & Petruzzi, Plenty of Blame, pp. 19–32; Longacre, pp. 154–56; Sears, pp. 106, 130–31; Gottfried, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 199–200; Longacre, pp. 156–58; Wittenberg & Petruzzi, Plenty of Blame, pp. 47–64; Gottfried, p. 36.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 200–201; Wittenberg & Petruzzi, Plenty of Blame, pp. 65–117; Longacre, pp. 161, 172–79; Gottfried, p. 38.

- ↑ Wittenberg & Petruzzi, Plenty of Blame, pp. 139–56; Longacre, pp. 193–98; Gottfried, p. 40.

- ↑ Wittenberg & Petruzzi, Plenty of Blame, pp. 162–78; Longacre, pp. 198–202; Gottfried, p. 42.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 100–102.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 209, 219–20; Sears, pp. 121–23; Gottfried, p. 32.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 239–40; Sears, pp. 149–53.

- ↑ Symonds, pp. 41–43; Gottfried, p. 36; Sears, pp. 103–106, 124; Esposito, text for Map 94; Eicher, pp. 504–507; McPherson, p. 649.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 181, 189.

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 508–509, discounts Heth's claim because the previous visit by Early to Gettysburg would have made the lack of shoe factories or stores obvious. However, many mainstream historians accept Heth's account: Sears, p. 136; Foote, p. 465; Clark, p. 35; Tucker, pp. 97–98; Martin, p. 25; Gottfried, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Eicher, p. 508; Sears, pp. 137, 162; Tucker, pp. 99–102; Gottfried, p. 38.

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 510–21.

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 521–40.

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 540–49; Sears, pp. 467–68.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 226–31, 237–39, 240–44; Eicher, pp. 540–50.

- ↑ The Battle of Antietam, the culmination of Lee's first invasion of the North, had the largest number of casualties in a single day, about 23,000.

- ↑ Rawley, p. 147. Sauers, p. 827. McPherson, p. 665; McPherson cites the combination of Gettysburg and Vicksburg as the turning point.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 535–36; Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, p. 39; Longacre, p. 246; Brown, pp. 9–11; Sears, p. 471.

- ↑ Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, pp. 160–61; Longacre, p. 247; Sears, p. 481.

- ↑ Longacre, pp. 235–37.

- ↑ Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, pp. 5–26; Sears, pp. 471, 481.

- ↑ Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, pp. 152–55; Gottfried, p. 278; Coddington, p. 543.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 544–48; Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, pp. 46–47, 79–80; Gottfried, p. 280.

- ↑ Huntington, pp. 131–33; Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, 49–74; Sears, pp. 480–81; Brown, pp. 128–36, 184; Coddington, p. 548; Gottfried, pp. 278–81; Longacre, pp. 249–50. A historical marker on East Cemetery Hill at Gettysburg Battlefield uses the term "Fight" for the "Monterey Gap" action, Longacre uses "skirmish". All of the other references use the name "Monterey Pass". The number of wagons captured is disputed. Brown reports that local residents cited "400 or 500". Longacre cites sources for 40 (Stuart) and 150 (Union Col. Pennock Huey). Huntington cites 300.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 552–53; Sears, pp. 482–83; Gottfried, pp. 282–85.

- ↑ Sears, p. 484.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 555, 556, 564.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 565–66; Gottfried, p. 286.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 567–70; Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, pp. 258–64, 271–74; Gottfried, p. 288; Sears, pp. 488–89.

- ↑ Coddington, pp. 570–73; Sears, pp. 490–93; Gottfried, p. 288.

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 213; Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, p. 345.

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 213–14; Sears, pp. 496–97; Eicher, p. 596; Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, pp. 345–46.

- ↑ Coddington, p. 573.

- ↑ Eicher, pp. 597–98, 618–19; Wittenberg et al., One Continuous Fight, pp. 342–43.

- ↑ Sears, pp. 511–15.

References

- Brown, Kent Masterson. Retreat from Gettysburg: Lee, Logistics, & the Pennsylvania Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8078-2921-8.

- Busey, John W., and David G. Martin. Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg. 4th ed. Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 2005. ISBN 0-944413-67-6.

- Clark, Champ, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Gettysburg: The Confederate High Tide. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4758-4.

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 – June 13, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932714-30-2.

- Huntington, Tom. Pennsylvania Civil War Trails: The Guide to Battle Sites, Monuments, Museums and Towns. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8117-3379-3.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. ISBN 0-8032-7941-8.

- Loosbrock, Richard D. "Battle of Brandy Station." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Martin, David G. Gettysburg July 1. rev. ed. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0-938289-81-0.

- Mingus, Scott L., Sr. Flames beyond Gettysburg: The Gordon Expedition, June 1863. Ironclad Publishing, 2009. ISBN 0-9673770-8-0.

- Nye, Wilbur S. Here Come the Rebels! Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1984. ISBN 0-89029-080-6. First published in 1965 by Louisiana State University Press.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Sauers, Richard A. "Battle of Gettysburg." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Symonds, Craig L. American Heritage History of the Battle of Gettysburg. New York: HarperCollins, 2001. ISBN 0-06-019474-X.

- Wittenberg, Eric J., and J. David Petruzzi. Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart's Controversial Ride to Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie, 2006. ISBN 1-932714-20-0.

- Wittenberg, Eric J., J. David Petruzzi, and Michael F. Nugent. One Continuous Fight: The Retreat from Gettysburg and the Pursuit of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, July 4–14, 1863. New York: Savas Beatie, 2008. ISBN 978-1-932714-43-2.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Beneath a Northern Sky: A Short History of the Gettysburg Campaign. Wilmington, DE: SR Books (scholarly Resources, Inc.), 2003. ISBN 0-8420-2933-8.

- National Park Service battle descriptions

|

|

Further reading

- Bearss, Edwin C. Receding Tide: Vicksburg and Gettysburg: The Campaigns That Changed the Civil War. Washington DC: National Geographic Society, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4262-0510-1.

- Boritt, Gabor S., ed. The Gettysburg Nobody Knows. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-19-510223-1.

- Desjardins, Thomas A. These Honored Dead: How the Story of Gettysburg Shaped American Memory. New York: Da Capo Press, 2003. ISBN 0-306-81267-3.

- Frassanito, William A. Early Photography at Gettysburg. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1995. ISBN 1-57747-032-X.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2, Fredericksburg to Meridian. New York: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- Fremantle, Arthur J. L. The Fremantle Diary: A Journal of the Confederacy. Edited by Walter Lord. Short Hills, NJ: Burford Books, 2002. ISBN 1-58080-085-8. First published 1954 by Capicorn Books.

- Freeman, Douglas S. Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1946. ISBN 0-684-85979-3.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Scribner, 1934.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. The Third Day at Gettysburg and Beyond. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8078-4753-4.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. Three Days at Gettysburg: Essays on Confederate and Union Leadership. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-87338-629-9.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. Brigades of Gettysburg. New York: Da Capo Press, 2002. ISBN 0-306-81175-8.

- Gottfried, Bradley M. The Artillery of Gettysburg. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58182-623-4.

- Hall, Jeffrey C. The Stand of the U.S. Army at Gettysburg. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-253-34258-9.

- Harman, Troy D. Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0054-2.

- Laino, Philip, Gettysburg Campaign Atlas. 2nd ed. Dayton, OH: Gatehouse Press 2009. ISBN 978-1-934900-45-1.

- Longstreet, James. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992. ISBN 0-306-80464-6. First published in 1896 by J. B. Lippincott and Co.

- Petruzzi, J. David, and Steven Stanley. The Complete Gettysburg Guide. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-63-0.

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The First Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8078-2624-3.

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The Second Day. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8078-1749-X.

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8078-2118-7.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. New York: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 0-06-019363-8.

- Tucker, Glenn. High Tide at Gettysburg. Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1983. ISBN 978-0-914427-82-7. First published 1958 by Bobbs-Merrill Co.

- Wert, Jeffry D. Gettysburg: Day Three. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-85914-9.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||