German New Guinea

| German New Guinea | ||||||

| Deutsch-Neuguinea | ||||||

| German colony | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

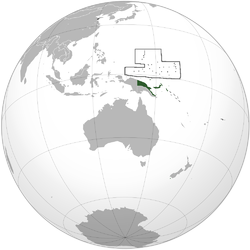

Green: German New Guinea | ||||||

| Capital | Herbertshöhe (Kokopo), Simpsonhafen (Rabaul) (after 1910) | |||||

| Languages | German (official), Austronesian languages, Papuan languages, German creoles | |||||

| Political structure | Colony | |||||

| Emperor | List of German monarchs | |||||

| Governor | List of colonial heads of New Guinea | |||||

| Historical era | German colonisation in the Pacific Ocean | |||||

| • | Colonization | 3 November 1884 | ||||

| • | Treaty of Versailles | 28 June 1919 | ||||

| Currency | Goldmark | |||||

| Today part of | | |||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Papua New Guinea |

|

| Papua New Guinea portal |

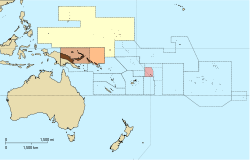

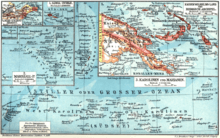

German New Guinea (German: Deutsch-Neuguinea) was the first part of the German colonial empire. It was a protectorate from 1884 until 1914 when it fell to Australian forces following the outbreak of the First World War. It consisted of the northeastern part of New Guinea and several nearby island groups. The mainland part of German New Guinea and the nearby islands of the Bismarck Archipelago and the North Solomon Islands are now part of Papua New Guinea. The Micronesian islands of German New Guinea are now governed as the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, the Northern Mariana Islands and Palau.

The mainland portion, Kaiser-Wilhelmsland, was formed from the northeastern part of New Guinea. The islands to the east of Kaiser-Wilhelmsland, on annexation, were renamed the Bismarck Archipelago (formerly the New Britannia Archipelago) and the two largest islands renamed Neu-Pommern ("New Pomerania", today's New Britain) and Neu-Mecklenburg ("New Mecklenburg, now New Ireland).[1] Due to their accessibility by water, however, these outlying islands were, and have remained, the most economically viable part of the territory.

With the exception of German Samoa, the German islands in the Western Pacific formed the "Imperial German Pacific Protectorates". These were administered as part of German New Guinea and they included the German Solomon Islands (Buka, Bougainville, and several smaller islands), the Carolines, Palau, the Marianas (except for Guam), the Marshall Islands, and Nauru. The total land area of German New Guinea was 249,500 square kilometres (96,300 sq mi).[2]

History

Early German South Pacific presence

The first Germans in the South Pacific were probably sailors on the crew of ships of the Dutch East India Company: during Abel Tasman's first voyage, the captain of the Heemskerck was one Holleman (or Holman), born in Jever in northwest Germany.[3][4] Hanseatic League merchant houses were the first to establish footholds: Johann Cesar Godeffroy & Sohn of Hamburg, headquartered at Samoa from 1857, operated a South Seas network of trading stations especially dominating the copra trade and carrying German immigrants to various South Pacific settlements;[5][6][7] in 1877 another Hamburg firm, Hernsheim and Robertson, established a German community on Matupi Island, in Blanche Bay (the north-east coast of New Britain) from which it traded in New Britain, the Caroline, and the Marshall Islands.[8][9] By the end of 1875, one German trader reported: "German trade and German ships are encountered everywhere, almost at the exclusion of any other nation".[10]

German colonial policy under Bismarck

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, an active minority, stemming mainly from a right-wing National Liberal and Free Conservative background, had organised various colonial societies all over Germany to persuade Chancellor Bismarck to embark on a colonial policy. The most important ones were the Kolonialverein of 1882 and the Society for German Colonization (Gesellschaft für Deutsche Kolonisation) founded in 1884.[11] The reasons for Bismarck's lack of enthusiasm when it came to the subject of Germany's colonial possessions is reflected in his curt response in 1888 to the procolonial, expansionist remarks of Eugen Wolf, reflected in the latter's autobiography. After Bismarck had patiently listened to Wolf enthusiastically laying out his plans that he sought to pitch employing several illustrative maps, Bismarck finally interrupted his monologue:

- "Your map of Africa there is very nice I have to admit. But you know, my map of Africa is here ... in Europe. You see here is Russia, over there is [..] France. And us, we are here – right in the middle between those two. That's my map of Africa."[12]

Despite his personal objections, it was Bismarck himself who eventually organised the acquisition of much of what would become the German colonial empire. The very first attempts at the new policy came in 1884 when Bismarck had to put German trading interests in southwestern Africa under imperial protection.[13] Bismarck told the Reichstag on 23 June 1884 of the change in German colonial policy: annexations would now proceed but by grants of charters to private companies.[14]

Australian aspiration and British disinterest

The edition of 27 November 1882 of the Augsburg Allgemeine Zeitung carried an article which the Colonial Secretary of the British colony of New South Wales drew to the attention of the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald and, on 7 February 1883, the paper published a summary of the article under the heading German annexation of New Guinea. The argument lifted from the German paper began by stating that New Guinea fell into the Australian sphere but had been neglected; although the Portuguese had explored in the 16th century, it was the Dutch from the 17th century "who seemed better satisfied with the country than other European nations had been" but they had over-reached themselves and had fallen back towards Java, Sumatra and Celebes. Recent explorations had given the basis for reconsideration: it "is considered useful by geology and biology people as holding in its forests the key to solve problems... a profitable field for cultivation" but London had only sent missionaries to save souls. "As we Germans have learnt a little about conducting colonial policy, and as our wishes and plans turn with a certain vivacity towards New Guinea... according to our opinion it might be possible to create out of the island a German Java, a great trade and plantation colony, which would form a stately foundation stone for a German colonial kingdom of the future."

The publication of the Sydney Morning Herald article caused a sensation and not just in the colony of New South Wales: over the border, in the British colony of Queensland[15] where the shipping lanes of the Torres Strait and the beche-de-mer trade were of commercial significance,[16] the Queensland Premier, Sir Thomas McIlwraith who led a political party "considered to represent the interests of the plantation owners in Queensland",[15] drew it to the attention of the Queensland Governor together with the general situation in New Guinea and urged annexation of the island.[17] He also instructed the London Agent for Queensland to urge the Imperial Colonial Office to an act of annexation.[18]

"Impatient with the lack of results from this procedure" Premier McIlwraith on his own authority ordered a Queensland Police Magistrate in March 1883 to proclaim the annexation on behalf of the Queensland government[17] of New Guinea east of the Dutch boundary at 141E.[19] When news of this reached London, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Derby promptly repudiated the act.[1][17] When the matter came before Parliament, Lord Derby advised that the British Imperial Government "were not ready to annex New Guinea in view of its vast size and unknown interior, the certainty of native objections and administrative expense".[20]

German New Guinea Company

On his return to Germany from his 1879–1882 Pacific expedition, Otto Finsch joined a small, informal group interested in German colonial expansion into the South Seas led by the banker, Adolph von Hansemann. Finsch encouraged them to pursue the founding of a colony on the north-east coast of New Guinea and the New Britain Archipelago even providing them with an estimate of the costs of such a venture.[21]

On 3 November 1884, under the auspices of the Deutsche Neuguinea-Compagnie (New Guinea Company), the German flag was flown over Kaiser-Wilhelmsland, the Bismarck Archipelago and the German Solomon Islands.

Albert Hahl (1868–1945) joined the German Colonial Office in 1895 and until 1914 played a major part in New Guinea's administration. He was an imperial judge at Herbertshoehe (1896–98), deputy governor of New Guinea (1899–1901), and governor (1902–14) As a judge he made three reforms: 1) the appointment of 'luluais' [village chiefs], 2) attempts to integrate the Tolais people into the European economy, and 3) the protection of village lands, which led him to recommend the ending of all alienation of native lands. After 1901 Hahl attempted to apply his system to the whole of New Guinea, and although his success was limited, exports rose from one million marks in 1902 to eight million in 1914. He was forced to retire because of disagreements with Berlin officials, and became an active writer on New Guinea and was a leader in German colonial societies between the wars.[22]

Lutheran and Catholic missions

By the mid-1880s German church authorities had devised a definite program for missionary work in New Guinea and assigned it to the Rhenish Mission, under the direction of Friedrich Fabri (1824–91), a Lutheran. The missionaries faced extraordinary difficulties: repeated sickness from the unhealthy climate; psychological and sometimes violent tensions and fights between the colonial administration and the natives. The natives rejected European customs and norms of social behaviour; few embraced Christianity. In 1921 the Rhenish Mission territory was handed over to the United Evangelical Lutheran Church of Australia.[23]

Missionaries sponsored by the Catholic Church in Germany had superior resources and influence, and proved more successful. They put more emphasis on tradition and less on modernisation, and were more in line with native world-views and traditions, European morality and discipline were often adopted, as were notions of dignity and prestige.[24]

Imperial German Pacific Protectorates

In the German–Spanish Treaty of 1899, the German government agreed to pay Spain 25,000,000 pesetas (equivalent to 16,600,000 goldmarks) for the Caroline Islands and the Mariana Islands (excluding Guam, which had been ceded to the US after the 1898 Spanish–American War). These islands became a protectorate and were administered from German New Guinea.[25] The Marshall Islands were added in 1906.

Forced labour policy

To expand the highly profitable plantations the Germans needed more native workers. The government sent military expeditions to take direct control of more areas from 1899 to 1914. Instead of voluntary recruitment it became a matter of forced mobilisation. The government enforced new laws that required the tribes to furnish four weeks of labour per person annually and payment of a poll tax in cash, thereby forcing reluctant natives into the work force. The government did explore the choice of voluntary recruitment of labourers from China, Japan, and Micronesia, but only a few hundred came. After 1910 the government tried to ameliorate the impact by ending the recruitment of women in some areas and entirely closing other areas to recruiting. The planters protested vehemently, and the government responded by sending troops to fresh areas to impose the labour policy .[26]

World War I

Following the outbreak of World War I, Australian troops captured Kaiser-Wilhelmsland and the nearby islands in 1914, after a short resistance led by captain Carl von Klewitz and Lt. Robert "Lord Bob" von Blumenthal, while Japan occupied most of the remaining German possessions in the Pacific. The only significant battle occurred on 11 September 1914 when the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force attacked the low-power wireless station at Bita Paka (near Rabaul) on the island of New Britain, then Neu Pommern. The Australians suffered six dead and four wounded – the first Australian military casualties of the First World War. The German forces fared much worse, with one German officer and 30 native police killed and one German officer and ten native police wounded. On 21 September all German forces in the colony surrendered.

However, Leutnant (later Hauptmann) Hermann Detzner, a German officer, and some 20 native police evaded capture in the interior of New Guinea for the entire war. Detzner was on a surveying expedition to map the border with Australian-held Papua at the outbreak of war, and remained outside militarised areas. Detzner claimed to have penetrated the interior of the German portion (Kaiser Wilhelmsland) in his 1920 book Vier Jahre unter Kannibalen ("Four Years Among Cannibals"). These claims were heavily disputed by various German missionaries, and Detzner recanted most of his claims in 1932.

After the Treaty of Versailles of 1919, Germany lost all its colonial possessions, including German New Guinea. In 1923, the League of Nations gave Australia a trustee mandate over Nauru, with the United Kingdom and New Zealand as co-trustees.[27] Other lands south of the equator became the Territory of New Guinea, a League of Nations Mandate Territory under Australian administration until 1949 (interrupted by Japanese occupation during the New Guinea campaign) when it was merged with the Australian territory of Papua to become the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, which eventually became modern Papua New Guinea. The islands north of the equator became the Japanese League of Nations Mandate for the South Seas Islands. After Japan's defeat in World War II, the former Japanese mandate islands were administered by the United States as the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, a United Nations trust territory.

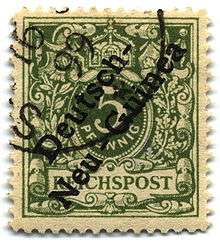

Postage stamps

The first postage stamps of the colony were issued in 1897, as overprints reading "Deutsch – / Neu-Guinea" on the contemporary stamps of Germany. In 1901, the Yacht issue included stamps for the colony, inscribed "DEUTSCH-NEU-GUINEA". The 5pf, 10pf, and 5m values were reprinted in 1914 on watermarked paper and inscribed "DEUTSCH-NEUGUINEA", but these did not reach the colony before it was occupied and were never put in use, nor was the reprint of the 3pf value made in 1919.

The stamps are available to collectors today at prices ranging from about $1 US, up to $500 for a validly used 5m stamp. Very few stamps of the higher values were ever used, and their prices are 10–20 times higher than for mint copies. Fake cancellations exist.

After the Australian occupation, stocks of the unwatermarked stamps, along with some registration labels, were overprinted with "G.R.I." and a value in pence or shillings; see New Britain for further details.

See also

- New Guinea

- List of colonial heads of New Guinea

- British New Guinea

- Dutch New Guinea

- Unserdeutsch language

- Kaiser-Wilhelmsland

References

- 1 2 William Churchill, 'Germany's Lost Pacific Empire' (1920) Geographical Review 10 (2) pp84-90 at p84

- ↑ ''. Deutsche Schutzgebiete page on New Guinea.

- ↑ Chronology of Germans in Australia

- ↑ Gutenberg Australia Abel Janszoon Tasman's Journal, edited by J E Heeres (1898), see descriptive note.

- ↑ Townsend, M. E. (1943) "Commercial and Colonial Policies" The Journal of Economic History 3 pp 124–134 at p 125

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Ohff (2008) Empires of enterprise: German and English commercial interests in East New Guinea 1884 to 1914 Thesis (PhD University of Adelaide, School of History and Politics) at p 10.

- ↑ "Godeffroy and Son possibly controlled as much as 70 per cent of the commerce of the South Seas" Kennedy, P. M. (1972) Bismarck's Imperialism: The Case of Samoa, 1880–1890 The Historical Journal 15(2) pp 261–283 citing H. U. Wehler Bismarck und der Imperialismus (1969) pp 208–15; E. Suchan-Galow Die deutsche Wirtschaftsta"tigkeit in der Südsee vor der ersten Besitzergreifung (1884) (Vero"ffentlichung des Vereins für Hamburgische Geschichte, Bd. XIV, Hamburg, 1940).

- ↑ Romilly, H. H. (1887) "The Islands of the New Britain Group" Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, New Monthly Series 9(1) pp 1–18 at p 2.

- ↑ Townsend, M. E. (1943) "Commercial and Colonial Policies" The Journal of Economic History 3 pp 124–134 at p 125.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Ohff (2008) Empires of enterprise: German and English commercial interests in East New Guinea 1884 to 1914 Thesis (Ph.D.) University of Adelaide, School of History and Politics p 26 quoting Schleinitz to Admiralty, 28 December 1875, Drucksache zu den Verhandlungen des Bundesrath, 1879, vol. 1, Denkschrift, xxiv–xxvii, p. 3.

- ↑ Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, "Domestic Origins of Germany's Colonial Expansion under Bismarck" (1969) Past & Present 42 pp 140–159 at p 144 citing R. V. Pierard, "The German Colonial Society, 1882–1914" (Iowa State University, PhD thesis, 1964); K. Klauss, Die Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft und die deutsche Kolonialpolitik von den Anfangen bis 1895 (Humboldt Universitat, East Berlin, PhD thesis, 1966); F. F. Muller, Deutschland-Zanzibar-Ostafrika. Geschichte einer deutschen Kolonialeroberung (Berlin, 1959).

- ↑ Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, "Domestic Origins of Germany's Colonial Expansion under Bismarck" (1969) Past & Present 42 pp 140–159 at p 144 citing Deutsches Zentralarchiv Potsdam, Reichskanzlei 7158.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Ohff (2008) Empires of enterprise: German and English commercial interests in East New Guinea 1884 to 1914 Thesis (Ph.D.) University of Adelaide, School of History and Politics p 62. "It is the aim of this thesis to demonstrate that specific and identifiable commercial interests, rather than politicians, defence or strategic concerns, ideology or morality were the driving forces behind what did or did not happen in the first 50 years of European settlement in East New Guinea and adjacent islands." at p 10.

- ↑ Hans-Jürgen Ohff (2008) Empires of enterprise: German and English commercial interests in East New Guinea 1884 to 1914 Thesis (Ph.D.) University of Adelaide, School of History and Politics p 62-63 citing R. M. Smith (tr.) (1885) German Interests in the South Sea, abstracts of the White Book presented to the Reichstag, December 1884 and February 1885 and pinpoint reference 1884, Wb no. 19, p. 37; he adds "a full translation of Bismarck's speech was published by The Times on 25 June 1884 under the rubric 'German Colonial Policy', pp. 10–3."

- 1 2 Donald C. Gordon, 'Beginnings of an Australasian Pacific Policy' (1945) Political Science Quarterly 60 (1) pp 79–89 at p 84

- ↑ Donald C. Gordon, 'Beginnings of an Australasian Pacific Policy' (1945) Political Science Quarterly 60 (1) pp 79–89 at p 84 citing statistics from Queensland Legislative Assembly, Votes and Proceedings 1883 p 776

- 1 2 3 Donald C. Gordon, 'Beginnings of an Australasian Pacific Policy' (1945) Political Science Quarterly 60 (1) pp 79–89 at p 85

- ↑ Donald C. Gordon, 'Beginnings of an Australasian Pacific Policy' (1945) Political Science Quarterly 60 (1) pp 79–89 at p 85 citing Queensland Legislative Assembly, Votes and Proceedings 1883 p 776

- ↑ William Churchill, 'Germany's Lost Pacific Empire' (1920) Geographical Review 10 (2) pp 84–90 at p 84

- ↑ I. M. Cumpston 1963 The Discussion of Imperial Problems in the British Parliament, 1880–85 Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fifth Series 13 pp 29–47 at p 42 citing Hansard, Parliamentary Debates 3rd Series cclxxxi 19

- ↑ P. G. Sack 'Finsch, Otto (1839–1917)' Australian Dictionary of Biography

- ↑ Peter By: Biskup, "Dr. Albert Hahl – Sketch of a German Colonial Official," Australian Journal of Politics and History (1968) 14#3 pp342-357

- ↑ Klaus-J. Bade. "Colonial Missions And Imperialism: The Background to the Fiasco of the Rhenish Mission in New Guinea," Australian Journal of Politics and History (1975) 21#2 pp 73–94.

- ↑ Hempenstall, Peter J. (1975). "The Reception of European Missions in the German Pacific Empire: The New Guinea Experience". Journal of Pacific History 10 (1): 46–64. doi:10.1080/00223347508572265.

- ↑ Caroline Islands Timeline

- ↑ Firth, Stewart (1976). "The Transformation of the Labour Trade in German New Guinea, 1899-1914". Journal of Pacific History 11 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1080/00223347608572290.

- ↑ Hudson, WJ (April 1965). "Australia's experience as a mandatory power". Australian Outlook 19 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1080/10357716508444191.

Further reading

- Peter Biskup: Hahl at Herbertshoehe, 1896–1898: The Genesis of German Native Administration in New Guinea, in: K. S. Inglis (ed.): History of Melanesia, Canberaa – Port Moresby 1969, 2nd ed. 1971, 77–99.

- Firth, Stewart: Albert Hahl: Governor of German New Guinea. In: Griffin, James, Editor : Papua New Guinea Portraits: The Expatriate Experience. Canberra: Australian National University Press; 1978: 28–47.

- Firth, S. G.: The New Guinea Company, 1885–1899: A Case of Unprofitable Imperialism. in: Historical Studies. 1972; 15: 361–377.

- Firth, Stewart G.: Arbeiterpolitik in Deutsch-Neuguinea vor 1914. In: Hütter, Joachim; Meyers, Reinhard; Papenfuss, Dietrich, Editors: Tradition und Neubeginn: Internationale Forschungen zur deutschen Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert. Köln: Carl Heymanns Verlag KG; 1975: 481–489.

- Noel Gash – June Whittaker: A pictorial history of New Guinea, Jacaranda Press: Milton, Queensland 1975, 312 p., ISBN 186273 025 3.

- Whittaker, J L; Gash, N. G.; Hookey, J. F.; and Lacey R. J. (eds.) : Documents and Readings in New Guinea History: Prehistory to 1889, Jacaranda Press: Brisbane 1975/1982

- Firth, Stewart (1973). "German Firms in the Western Pacific Islands". Journal of Pacific History 8 (1): 10–28. doi:10.1080/00223347308572220.

- Firth, Stewart G.: German Firms in the Pacific Islands, 1857– 1914. In: Moses, John A.; Kennedy, Paul M., Editors. Germany in the Pacific and Far East, 1870–1914. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press; 1977: 3–25

- Firth, Stewart (1985). "German New Guinea: The Archival Perspective". Journal of Pacific History 20 (2): 94–103. doi:10.1080/00223348508572510.

- Firth, Stewart: The Germans in New Guinea. In: May, R. J.; Nelson, Hank, Editors: Melanesia: Beyond Diversity. Canberra: Australian National University, Research School of Pacific Studies; 1982: 151–156.

- Firth, Stewart (1976). "The Transformation of the Labour Trade in German New Guinea, 1899-1914". Journal of Pacific History 11 (1): 51–65. doi:10.1080/00223347608572290.

- Firth, Stewart. Labour in German New Guinea. In: Latukefu, Sione, Editor. Papua New Guinea: A Century of Colonial Impact 1884–1984. Port Moresby: The National Research Institute and the University of Papua New Guinea in association with the PNG Centennmial Committee; 1989: 179–202.

- Moses, John, and Kennedy, Paul, Germany in the Pacific and Far East 1870–1914, St Lucia Qld: Queensland University Press, 1977. ISBN 9780702213304

- Sack, Peter, ed., German New Guinea: A Bibliography, Canberra ACT: Australian National University Press, 1980, ISBN 9780909596477

- Firth, Stewart: New Guinea Under the Germans, Melbourne University Press : International Scholarly Book Services: Carlton, Vic. 1983, ISBN 9780522842203, reprinted by WEB Books: Port Moresby 1986, ISBN 9980570105.

- Foster, Robert J. (1987). "Komine and Tanga: A Note on Writing the History of German New Guinea". Journal of Pacific History 22 (1): 56–64. doi:10.1080/00223348708572551.

- Mary Taylor Huber: The Bishops’ Progress. A Historical Ethnography of Catholic Missionary Experience of Catholic Missionary Experience on the Sepik Frontier, Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington and London 1988, 264 pp., ISBN 0-87474-544-6.

- Mary Taylor Huber: The Bishops’ Progress: Representations of Missionary Experience on the Sepik Frontier, in: Nancy Lutkehaus (ed.): Sepik Heritage. Tradition and Change in Papua New Guinea, Crawford House Press: Bathurst, NSW (Australia) 1990, 663 pp. + 3 maps, ISBN 1-86333-014-3., pp. 197–211.

- Keck, Verena. "Representing New Guineans in German Colonial Literature," Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde (2008), Vol. 54, pp 59–83.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|