Chancellor of Germany (1949–)

| Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany

Bundeskanzler(in) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Member of |

Cabinet European Council |

| Seat |

German Chancellery, Berlin, Germany (primary) Palais Schaumburg, Bonn, Germany (secondary) |

| Appointer |

The Federal President In accordance with a vote in the Bundestag |

| Term length |

None The Chancellor's term of office ends when a new Bundestag ("Federal Diet", the lower house of the German Federal Parliament) convenes for its first meeting or when dismissed by the President (for instance following a constructive vote of no confidence),[1] i.e. usually 4 years (unlimited during state of defence) |

| Constituting instrument | Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany |

| Formation | 1949 |

| First holder | Konrad Adenauer |

| Deputy | Vice-Chancellor |

| Salary | €220,000 p.a. |

| Website | www.bundeskanzlerin.de |

The Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (in German called Bundeskanzler(in), literally "Federal Chancellor", or Kanzler for short) is, under the German 1949 constitution, the head of government of Germany. It is historically a continuation of the office of Chancellor (German: Kanzler, later Reichskanzler, Chancellor of the Realm) that was originally established as the office of Chancellor of the North German Confederation in 1867. The 1949 constitution increased the role of the Chancellor compared to the 1919 Weimar Constitution by making the Chancellor much more independent of the influence of the Federal President and granting the Chancellor the right to set the guidelines for all policy areas, thus making him the real chief executive.[2] The role is generally comparable to that of Prime Minister in other parliamentary democracies.

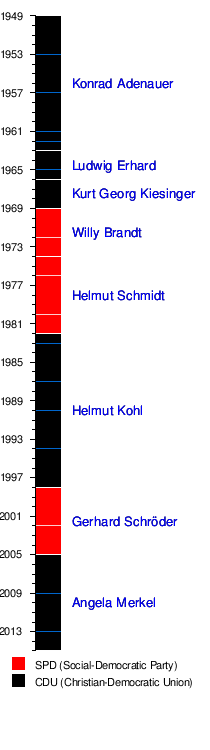

There have been eight chancellors since 1949. The current Chancellor of Germany is Angela Merkel, who was elected in 2005. She is the first female Chancellor since the establishment of the original office in 1867, and known in German as Bundeskanzlerin, the feminine form of Bundeskanzler. Merkel is also the first Chancellor elected since the fall of the Berlin Wall to have been raised in the former East Germany.

History of position

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Germany |

|

| Foreign relations |

|

Politics portal |

The office of Chancellor has a long history, stemming back to the Holy Roman Empire. The title was at times used in several states of German-speaking Europe. The power and influence of this office varied strongly over time. Otto von Bismarck in particular had a great amount of power, but it was not until 1949 that the Chancellor was established as the central executive authority of Germany.

Due to his administrative tasks, the head of the chapel of the imperial palace during the Holy Roman Empire was called Chancellor. The Archbishop of Mainz was German Chancellor until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 while the Archbishop of Cologne was Chancellor of Italy and the Archbishop of Trier of Burgundy. These three Archbishops were also Prince-electors of the empire. Already in medieval times the Chancellor had political power like Willigis of Mainz (Archchancellor 975–1011, regent for Otto III 991–994) or Rainald von Dassel (Chancellor 1156–1162 and 1166–1167) under Frederick I.

The modern office of Chancellor was established with the North German Confederation, of which Otto von Bismarck became Chancellor of the Confederation (official German title: Bundeskanzler) in 1867. After unification of Germany in 1871, the office became known in German as Reichskanzler ("Reich Chancellor", literally "Chancellor of the Realm"). Since the adoption of the current constitution of Germany (the "Basic Law" or "Grundgesetz") in 1949 the formal title of the office is once again Bundeskanzler (Federal Chancellor).

In the now defunct German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany), which existed from 7 October 1949 to 3 October 1990 (when the territory of the former GDR was reunified with the Federal Republic of Germany), the position of Chancellor did not exist. The equivalent position was called either Minister President (Ministerpräsident) or Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the GDR (Vorsitzender des Ministerrats der DDR). (See Leaders of East Germany.)

- See the article Chancellor for the etymology of the word.

Role

West Germany's 1949 constitution, the Basic Law (Grundgesetz), invests the Federal Chancellor (Bundeskanzler) with central executive authority. Since the 1961 election, the two major parties (CDU/CSU and SPD) call their leading candidates for the federal election "chancellor-candidate" (Kanzlerkandidat), although this is not an official term and any party can nominate a Kanzlerkandidat (even if there is no chance at all to lead or even become part of a government coalition). The Federal Government (Bundesregierung) consists of the Federal Chancellor and his or her cabinet ministers, called Bundesminister (Federal Ministers).

The chancellor's authority emanates from the provisions of the Basic Law and from his or her status as leader of the party (or coalition of parties) holding a majority of seats in the Bundestag ("Federal Diet", the lower house of the German Federal Parliament). With the exception of Helmut Schmidt, the chancellor has usually also been chairman of his or her own party. This was the case with Chancellor Gerhard Schröder from 1999 until he resigned the chairmanship of the SPD in 2004.

The first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, set many precedents that continue today. He arrogated nearly all major decisions to himself, and established the chancellorship as the clear focus of power in Germany. He often treated his ministers as mere extensions of his authority rather than colleagues - which they are according to the German constitution as the Chancellor sets the guidelines for all fields of government policy. While his successors have tended to be less domineering, the chancellor has acquired enough ex officio authority (in addition to his constitutional powers) that Germany is often described by constitutional law experts as a "chancellor democracy."

The chancellor determines the composition of the Federal Cabinet. The President formally appoints and dismisses cabinet ministers, at the recommendation of the chancellor; no parliamentary approval is needed. According to the Basic Law, the chancellor may set the number of cabinet ministers and dictate their specific duties. Chancellor Ludwig Erhard had the largest cabinet, with twenty-two ministers in the mid-1960s. Helmut Kohl presided over 17 ministers at the start of his fourth term in 1994; the 2002 cabinet, the second of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, had 13 ministers and the Angela Merkel cabinet as of 22 November 2005 has 15.

Article 65 of the Basic Law sets forth three principles that define how the executive branch functions:

- The "chancellor principle" makes the chancellor responsible for all government policies which is also known as the Richtlinienkompetenz (roughly translated as "guideline setting competence"). Any formal policy guidelines issued by the chancellor are legally binding directives that cabinet ministers must implement. Cabinet ministers are expected to introduce specific policies at the ministerial level that reflect the chancellor's broader guidelines.

- The "principle of ministerial autonomy" entrusts each minister with the freedom to supervise departmental operations and prepare legislative proposals without cabinet interference so long as the minister's policies are consistent with the chancellor's broader guidelines.

- The "cabinet principle" calls for disagreements between federal ministers over jurisdictional or budgetary matters to be settled by the cabinet.

Appointment mechanism

Every four years, after national elections and the convocation of the newly elected members of the Bundestag ("Federal Diet", the lower house of the German Federal Parliament), the Federal Chancellor is elected by a majority of the members of the Bundestag upon the proposal of the President (Bundespräsident, literally "Federal President"). This vote is one of the few cases where a majority of all elected members of the Bundestag must be achieved, as opposed to a mere majority of those that are currently assembled. This is referred to as the Kanzlermehrheit (chancellor's majority), and is designed to ensure the establishment of a stable government. It has in the past occasionally forced ill or pregnant members to have to attend parliament when a party's majority was only slim.

Unlike regular voting by the Bundestag, the vote to elect the chancellor is by secret ballot. This is intended to ensure that the chancellor's majority does not depend on members of his or her party only outwardly showing support.

If the nominee of the President is not elected, the Bundestag may elect its own nominee within fourteen days. If no-one is elected within this period, the Bundestag will attempt an election. If the person with the highest number of votes has a majority, the President must appoint him or her. If the person with the highest number of votes does not have a majority, the President may either appoint them or call new elections for the Bundestag. As all chancellors have been elected in the first vote as yet (1949–2010) neither of these constitutional provisions has been applied.

The Federal Chancellor is the only member of the federal government elected by the Bundestag. The other cabinet ministers (called Bundesminister, "Federal Ministers") are chosen by the Federal Chancellor himself or herself, although they are formally appointed by the Federal President on the Federal Chancellor's proposal.

Confidence

Unlike in other parliamentary legislatures, the Bundestag or Federal Diet (lower house of the German Federal Parliament) cannot remove the Chancellor with a traditional motion of no confidence. Instead, the removal of a Chancellor is only possible when the majority of the Bundestag members agrees on a successor, who is then immediately sworn in as new Federal Chancellor. This procedure is called "constructive motion of no confidence" (konstruktives Misstrauensvotum) and was created to avoid the situation that existed in the Weimar Republic, where it was easier to gather a parliament majority willing to remove a government in office than to find a majority capable of supporting a new stable government.[3]

In order to garner legislative support in the Bundestag, the chancellor can also ask for a motion of confidence (Vertrauensfrage, literally "question of trust"), either combined with a legislative proposal or as a standalone vote. Only if such a vote fails may the Federal President dissolve the Bundestag.

Style of address

The correct style of address in German is Herr Bundeskanzler (male) or Frau Bundeskanzlerin (female). Use of the mixed form "Frau Bundeskanzler" was deprecated by the government in 2004 because it is regarded as impolite.[4]

List of Chancellors

Salary

Holding the third-highest state office available within the Federal Republic of Germany, the Chancellor of Germany receives €220,000 per annum and a €22,000 bonus, i.e. one and two thirds of Salary Grade B11 (according to § 11 (1) a of the Federal Law on Ministres – Bundesministergesetz, BGBl. 1971 I p. 1166 and attachment IV to the Federal Law on Salaries of Officers – Bundesbesoldungsgesetz, BGBl. 2002 I p. 3020).

See also

- Air transports of heads of state and government

- Official state car

- Politics of Germany

- History of Germany

- President of Germany

- Leaders of East Germany

- Chancellor of Germany (German Reich)

- List of Chancellors of the Federal Republic of Germany by time in office

- List of state leaders

- Religious affiliations of Chancellors of Germany

References

- ↑ "Acting in accordance with the constitution". Regierungonline. The Press and Information Office of the Federal Government of Germany. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ↑ http://www.bundespraesident.de/EN/Role-and-Functions/ConstitutionalBasis/ConstitutionalBasis-node.html

- ↑ Meyers Taschenlexikon Geschichte vol.2 1982

- ↑ "Frau Bundeskanzler" oder ... "Frau Bundeskanzlerin"? - n-tv.de

Further reading

Books

- Klein, Herbert, ed. 1993. The German Chancellors. Berlin: Edition.

- Padgett, Stephen, ed. 1994. The Development of the German Chancellorship: Adenauer to Kohl. London: Hurst.

Articles

- Harlen, Christine M. 2002. "The Leadership Styles of the German Chancellors: From Schmidt to Schröder." Politics and Policy 30 (2 (June)): 347–371.

- Helms, Ludger. 2001. "The Changing Chancellorship: Resources and Constraints Revisited." German Politics 10 (2): 155–168.

- Mayntz, Renate. 1980. "Executive Leadership in Germany: Dispersion of Power or 'Kanzler Demokratie'?" In Presidents and Prime Ministers, ed. R. Rose and E. N. Suleiman. Washington, D.C: American Enterprise Institute. pp. 139–71.

- Smith, Gordon. 1991. "The Resources of a German Chancellor." West European Politics 14 (2): 48–61.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chancellor of Germany . |

- Official site of German Chancellor (German and English)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|