George Whitefield

| George Whitefield | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Renowned English open air preacher and evangelist | |

| Born |

December 27, 1714 Gloucester, England |

| Died |

September 30, 1770 (aged 55) Newburyport, Province of Massachusetts Bay |

George Whitefield (December 27 [O.S. December 16] 1714 – September 30, 1770), also known as George Whitfield, was an English Anglican cleric who helped spread the Great Awakening in Britain and, especially, in the American colonies.

Born in Gloucester, England, he attended Pembroke College, Oxford University, where he met the Wesley brothers. He was one of the founders of Methodism and of the evangelical movement generally.[1] In 1740, Whitefield traveled to America, where he preached a series of revivals that came to be known as the "Great Awakening." He became perhaps the best-known preacher in Great Britain and North America during the 18th century. Because he traveled throughout the American colonies and drew thousands of people with his sermons, he was one of the most widely recognized public figures in colonial America.

Early life

Whitefield was born at the Bell Inn, Southgate Street, Gloucester in England. Whitefield was the fifth son (seventh child) of Thomas Whitefield and Elizabeth Edwards who kept an inn at Gloucester. At an early age, he found that he had a passion and talent for acting in the theatre, a passion that he would carry on with the very theatrical re-enactments of Bible stories he told during his sermons. He was educated at the Crypt School, Gloucester, and Pembroke College, Oxford.[2]

Because business at the inn had become poor, Whitefield did not have the means to pay for his tuition.[3] He therefore entered Oxford as a servitor, the lowest rank of students at Oxford. In return for free tuition, he was assigned as a minister to a number of higher ranked students. His duties included teaching them in the morning, helping them bathe, taking out their garbage, carrying their books and even assisting with required written assignments.[3] He was a part of the "Holy Club" at the University of Oxford with the Wesley brothers, John and Charles. An illness, as well as Henry Scougal's The Life of God in the Soul of Man, influenced him to cry out to God for salvation. Following a religious conversion, he became passionate for preaching his new-found faith. The Bishop of Gloucester ordained him a deacon.[4]

Evangelism

| Calvinism |

|---|

|

|

Peoples |

|

Organisation |

| Calvinism portal |

Whitefield preached his first sermon at St Mary de Crypt Church[5] in his home town of Gloucester, a week after his ordination. He had earlier become the leader of the Holy Club at Oxford when the Wesley brothers departed for Georgia.[6]

In 1738 he went to Savannah, Georgia, in the American colonies, as parish priest. While there he decided that one of the great needs of the area was an orphan house. He decided this would be his life's work. He returned to England to raise funds, as well as to receive priest's orders. While preparing for his return he preached to large congregations. At the suggestion of friends he preached to the miners of Kingswood, outside Bristol, in the open air. Because he was returning to Georgia he invited John Wesley to take over his Bristol congregations, and to preach in the open air for the first time at Kingswood and then at Blackheath, London.[7]

Whitefield accepted the Church of England's doctrine of predestination and disagreed with the Wesley brothers' views on the doctrine of the Atonement, Arminianism. As a result, Whitefield did what his friends hoped he would not do—hand over the entire ministry to John Wesley.[8] Whitefield formed and was the president of the first Methodist conference. But he soon relinquished the position to concentrate on evangelical work.[9]

Three churches were established in England in his name – one in Penn Street, Bristol, and two in London, in Moorfields and in Tottenham Court Road – all three of which became known by the name of "Whitefield's Tabernacle". The society meeting at the second Kingswood School at Kingswood, a town on the eastern edge of Bristol, was eventually also named Whitefield's Tabernacle. Whitefield acted as chaplain to Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, and some of his followers joined the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, whose chapels were built by Selina, where a form of Calvinistic Methodism similar to Whitefield's was taught. Many of Selina's chapels were built in the English and Welsh counties, and one was erected in London—Spa Fields Chapel.[10]

In 1739, Whitefield returned to England to raise funds to establish the Bethesda Orphanage, which is the oldest extant charity in North America. On returning to North America in 1740, he preached a series of revivals that came to be known as the Great Awakening of 1740. In 1740 he engaged Moravian Brethren from Georgia to build an orphanage for Negro children on land he had bought in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. Following a theological disagreement, he dismissed them but was unable to complete the building, which the Moravians subsequently bought and completed. This now is the Whitefield House in the center of the Moravian settlement of Nazareth. He preached nearly every day for months to large crowds of sometimes several thousand people as he traveled throughout the colonies, especially New England. His journey on horseback from New York City to Charleston was the longest then undertaken in North America by a white man.[11]

Like his contemporary and acquaintance, Jonathan Edwards, Whitefield preached staunchly Calvinist theology that was in line with the "moderate Calvinism" of the Thirty-nine Articles.[12] While explicitly affirming God's sole agency in salvation, Whitefield freely offered the Gospel, saying at the end of his sermons: "Come poor, lost, undone sinner, come just as you are to Christ."[13]

Revival meetings

The Anglican Church did not assign him a pulpit, so he began preaching in parks and fields in England on his own, reaching out to people who normally did not attend church. Like Jonathan Edwards, he developed a style of preaching that elicited emotional responses from his audiences. But Whitefield had charisma, and his voice (which according to many accounts, could be heard over five hundred feet), his small stature, and even his cross-eyed appearance (which some people took as a mark of divine favour) all served to help make him one of the first celebrities in the American colonies.[14]

Thanks to widespread dissemination of print media, perhaps half of all colonists eventually heard about, read about, or read something written by Whitefield. He employed print systematically, sending advance men to put up broadsides and distribute handbills announcing his sermons. He also arranged to have his sermons published.[15] A crowd Whitefield estimated at 30,000 met him in Cambuslang in 1742.

Benjamin Franklin and Whitefield

Benjamin Franklin attended a revival meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and was greatly impressed with Whitefield's ability to deliver a message to such a large group. Franklin had previously dismissed, as an exaggeration, reports of Whitefield preaching to crowds of the order of tens of thousands in England. When listening to Whitefield preaching from the Philadelphia court house, Franklin walked away towards his shop in Market Street until he could no longer hear Whitefield distinctly. He then estimated his distance from Whitefield and calculated the area of a semicircle centred on Whitefield. Allowing two square feet per person he computed that Whitefield could be heard by over thirty thousand people in the open air.[16][17]

Franklin admired Whitefield as a fellow intellectual but thought Whitefield's plan to run an orphanage in Georgia would lose money. He published several of Whitefield's tracts and was impressed by Whitefield's ability to preach and speak with clarity and enthusiasm to crowds. Franklin was an ecumenist and approved of Whitefield's appeal to members of many denominations, but was not, like Whitefield, an evangelical. In his autobiography, Franklin famously wrote that he was a "thoroughgoing Deist," which precludes the idea that God is personal, though some suggest that Franklin was more traditional in his views, e.g., his speech at the Constitutional Convention where he recited the verse that not a single sparrow falls to the ground without God's notice; how then could the Constitution convention hope to succeed without God's careful oversight?[18] After one of Whitefield's sermons, Franklin noted the:

wonderful... change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seem'd as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk thro' the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street." [19][20]

A lifelong close friendship developed between the revivalist preacher and the worldly Franklin. Looking beyond their public images, one finds a common charity, humility, and ethical sense embedded in the character of each man. True loyalty based on genuine affection, coupled with a high value placed on friendship, helped their association grow stronger over time.[21] Letters exchanged between Franklin and Whitefield can be found at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.[22] These letters document the creation of an orphanage for boys named the Charity School. And in 1749, Franklin chose the Whitefield meeting house, with its Charity School, to be purchased as the site of the newly formed Academy of Philadelphia which opened in 1751, followed in 1755 with the College of Philadelphia, both the predecessors of the University of Pennsylvania. A statue of George Whitefield is located in the Dormitory Quadrangle, standing in front of the Morris and Bodine sections of the present Ware College House on the University of Pennsylvania campus.[23]

Travels

Whitefield is remembered as one of the first to preach to the enslaved. Phillis Wheatley wrote a poem in his memory after he died.

In an age when crossing the Atlantic Ocean was a long and hazardous adventure, he visited America seven times, making thirteen ocean crossings in total. It is estimated that throughout his life, he preached more than 18,000 formal sermons, of which seventy-eight have been published[24] In addition to his work in North America and England, he made fifteen journeys to Scotland—most famously to the "Preaching Braes" of Cambuslang in 1742—two journeys to Ireland, and one each to Bermuda, Gibraltar, and the Netherlands.

He went to the Georgia Colony in 1738 following John Wesley's departure, to serve as a colonial chaplain at Savannah.

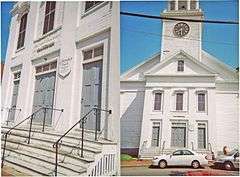

Death

Whitefield died in the parsonage of Old South Presbyterian Church,[25] Newburyport, Massachusetts, on September 30, 1770, and was buried, according to his wishes, in a crypt under the pulpit of this church. A bust of Whitefield is in the collection of the Gloucester City Museum & Art Gallery.

It was John Wesley who preached his funeral sermon in London, at Whitefield's request.[26]

Relation to other Methodist leaders

In terms of theology, Whitefield, unlike John Wesley, was a supporter of Calvinism. The two differed on eternal election, final perseverance, and sanctification, but were reconciled as friends and co-workers, each going his own way. It is a prevailing misconception that Whitefield was not primarily an organizer like Wesley. However, as Wesleyan historian Rev. Luke Tyerman states, "It is notable that the first Calvinistic Methodist Association was held eighteen months before Wesley held his first Methodist Conference."[27] He was a man of profound experience, which he communicated to audiences with clarity and passion. His patronization by the Countess of Huntingdon reflected this emphasis on practice.

Religious innovation

In the First Great Awakening, rather than listening demurely to preachers, people groaned and roared in enthusiastic emotion; new divinity schools opened to challenge the hegemony of Yale and Harvard; personal experience became more important than formal education for preachers. Such concepts and habits formed a necessary foundation for the American Revolution.[28][29]

Advocacy of slavery

In 1735, slavery had been outlawed in the young Georgia colony. In 1749, George Whitefield campaigned for its legalization, claiming that the territory would never be prosperous unless farms were able to use slave labor.[30] He began his fourth visit to America in 1751 advocating slavery; he considered its establishment in Georgia as necessary to make his plantation profitable.[31] His campaign may have played a role, but the Georgia Trustees re-authorized slavery in 1751 for economic reasons, to attract more settlers and raise the colony's profit. They had not been able to attract sufficient numbers of farmers who wanted to establish subsistence households.

Whitefield purchased slaves, who worked at his Bethesda Orphanage in Chatham County, Georgia. To help raise money for the orphanage, he also employed slaves at his Providence Plantation. Whitefield was known to treat his slaves well; they were reputed to be devoted to him, and he was critical of the abuse of slaves by other owners.[32] When Whitefield died, he bequeathed his slaves to the Countess of Huntingdon, who supported the evangelical movement.[33]

His attitude towards slavery is expressed in a letter to Mr B. written from Bristol 22 March 1751:

As for the lawfulness of keeping slaves, I have no doubt, since I hear of some that were bought with Abraham's money, and some that were born in his house.—And I cannot help thinking, that some of those servants mentioned by the Apostles in their epistles, were or had been slaves. It is plain, that the Gibeonites were doomed to perpetual slavery, and though liberty is a sweet thing to such as are born free, yet to those who never knew the sweets of it, slavery perhaps may not be so irksome. However this be, it is plain to a demonstration, that hot countries cannot be cultivated without negroes. What a flourishing country might Georgia have been, had the use of them been permitted years ago? How many white people have been destroyed for want of them, and how many thousands of pounds spent to no purpose at all? Had Mr Henry been in America, I believe he would have seen the lawfulness and necessity of having negroes there. And though it is true, that they are brought in a wrong way from their own country, and it is a trade not to be approved of, yet as it will be carried on whether we will or not; I should think myself highly favoured if I could purchase a good number of them, in order to make their lives comfortable, and lay a foundation for breeding up their posterity in the nurture and admonition of the Lord. You know, dear Sir, that I had no hand in bringing them into Georgia; though my judgement was for it, and so much money was yearly spent to no purpose, and I was strongly importuned thereto, yet I would not have a negro upon my plantation, till the use of them was publicly allowed in the colony. Now this is done, dear Sir, let us reason no more about it, but diligently improve the present opportunity for their instruction. The trustees favour it, and we may never have a like prospect. It rejoiced my soul, to hear that one of my poor negroes in Carolina was made a brother in Christ. How know we but we may have many such instances in Georgia ere it be long?[34]

Works

Whitefield's sermons were widely reputed to inspire his audience's enthusiasm. Many of them as well as his letters and journals were published during his lifetime. He was an excellent orator as well, strong in voice and adept at extemporaneity.[35] His voice was so expressive that people are said to have wept just hearing him allude to "Mesopotamia". His journals, originally intended only for private circulation, were first published by Thomas Cooper.[36][37] James Hutton then published a version with Whitefield's approval. His exuberant and "too apostolical" language were criticised; his journals were no longer published after 1741.[38]

Whitefield prepared a new installment in 1744–45, but it was not published until 1938. Nineteenth-century biographies generally refer to his earlier work, A Short Account of God's Dealings with the Reverend George Whitefield (1740), which covered his life up to his ordination. In 1747, he published A Further Account of God's Dealings with the Reverend George Whitefield, covering the period from his ordination to his first voyage to Georgia. In 1756, a vigorously edited version of his journals and autobiographical accounts was published.[39][40]

After Whitefield's death, John Gillies, a Glasgow friend, published a memoir and six volumes of works, comprising three volumes of letters, a volume of tracts, and two volumes of sermons. Another collection of sermons was published just before he left London for the last time in 1769. These were disowned by Whitefield and Gillies, who tried to buy all copies and pulp them. They had been taken down in shorthand, but Whitefield said that they made him say nonsense on occasion. These sermons were included in a nineteenth-century volume, Sermons on Important Subjects, along with the "approved" sermons from the Works. An edition of the journals, in one volume, was edited by William Wale in 1905. This was reprinted with additional material in 1960 by the Banner of Truth Trust. It lacks the Bermuda journal entries found in Gillies' biography and the quotes from manuscript journals found in 19th-century biographies. A comparison of this edition with the original 18th-century publications shows numerous omissions—some minor and a few major.[41]

Whitefield also wrote several hymns. In 1739, Charles Wesley composed a hymn, "Hark, how all the welkin rings”. In 1758, Whitefield revised the opening couplet for "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing."[42]

Veneration

Whitefield is honored together with Francis Asbury with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on November 15.

Whitfield County, Georgia, is named after the Reverend. When the act by the Georgia General Assembly was written to create the county, the "e" was omitted from the spelling of the name to reflect the pronunciation of the name.[43]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Noll 2010.

- ↑ "George Whitefield", Christian History, Christianity today, August 8, 2008.

- 1 2 Dallimore 2010, p. 13.

- ↑ "George Whitefield Methodist evangelist". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Heighway, Carolyn. Gloucester: a history and guide. Gloucester: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1985, p. 141. ISBN 0-86299-256-7

- ↑ "Chapter V: The Holy Club". Wesley Center. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ "Whitefield's Mount". Brethren Archive. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Wiersbe, Warren W (2009), 50 People Every Christian Should Know, pp. 42–43, ISBN 978-0-8010-7194-2.

- ↑ Holy Women, Holy Men: Celebrating the Saints. Church Publishing. 2010. p. 680. ISBN 9780898696783.

- ↑ "Coldbath Fields and Spa Fields". British History Online. Cassell, Petter & Galpin. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ "George Whitefield". Digital Puritan. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Whitefield 2001, p. 3:383.

- ↑ Bormann 1985, p. 73.

- ↑ "George Whitefield: Did You Know?". Christian History. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Stout, Harry S (1991), The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism.

- ↑ Franklin, pp. 163–64.

- ↑ Hoffer, Peter Charles (2011), When Benjamin Franklin Met the Reverend Whitefield: Enlightenment, Revival, and the Power of the Printed Word, Johns Hopkins University Press, 156 pp.

- ↑ "Franklin", US Constitution.

- ↑ Franklin, pp. 104–8.

- ↑ Rogal, Samuel J (1997), "Toward a Mere Civil Friendship: Benjamin Franklin and George Whitefield", Methodist History 35 (4): 233–43, ISSN 0026-1238.

- ↑ Brands, HW (2000), The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin, pp. 138–50.

- ↑ "Letter to George Whitefield; Philadelphia, June 17, 1753.". American Philosophical Society Library. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "George Whitefield Statue". Penn State University. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ Sermons of George Whitefield that have never yet been reprinted, Quinta.

- ↑ First Presbyterian (Old South) Church.

- ↑ Wesley, John (1951). "Entry for Nov. 10, 1770". The Journal of John Wesley (online). Chicago: Moody Press. p. 202.

- ↑ Dallimore 2010, p. 130.

- ↑ Ruttenburg, Nancy (1993), "George Whitefield, Spectacular Conversion, and the Rise of Democratic Personality", American Literary History 5 (3): 429–58, ISSN 0896-7148.

- ↑ Mahaffey 2011.

- ↑ Dallimore 1980.

- ↑ Lambert 1993, pp. 204–5.

- ↑ Pollock, John, George Whitefield: The Great Awakening, Christian Focus, 2009, ISBN 978-1-84550-454-0.

- ↑ Cashin, Edward J (2001), Beloved Bethesda : A History of George Whitefield's Home for Boys.

- ↑ Whitefield 2001, volume 2, letter DCCCLXXXVII.

- ↑ "George Whitefield". Christian History. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ "George Whitefield's Journals". Quinta Press. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Lam, George L.; Smith, Warren H. (1944). "Two Rival Editions of George Whitefield's "Journal," London, 1738". Studies in Philology 41 (1): 86–93.

- ↑ Lambert, Frank (2002). Pedlar in Divinity: George Whitefield and the Transatlantic Revivals, 1737-1770. Princeton University Press. pp. 77–84. ISBN 9780691096162.

- ↑ Kidd, Thomas S. (2014). George Whitefield: America's Spiritual Founding Father. Yale University Press. p. 269. ISBN 9780300181623.

- ↑ "The Works of George Whitefield Journals" (PDF). Quinta Press. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ "The Works of George Whitefield". Quinta Press. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ↑ Bowler, Gerry (December 29, 2013), "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing", UM Today (University of Manitoba).

- ↑ "Whitfield County History". Whitfield County. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

Further reading

- Armstrong, John H. Five Great Evangelists: Preachers of Real Revival. Fearn (maybe Hill of Fearn), Tain: Christian Focus Publications, 1997. ISBN 978-1-85792-157-1

- Bormann, Ernest G (1985), Force of Fantasy: Restoring the American Dream, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, ISBN 978-0-8093-2369-2.

- Dallimore, Arnold A. George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth-Century Revival (Volume I). Edinburgh or Carlisle: Banner of Truth Trust, 1970. ISBN 978-0-85151-026-2.

- ——— (1980), George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth-Century Revival II, Edinburgh or Carlisle: Banner of Truth Trust, ISBN 978-0-85151-300-3.

- ——— (2010), George Whitefield: God's Anointed Servant in the Great Revival of the Enlightened Century, Crossway, ISBN 978-1433513411.

- Franklin, Benjamin, The Autobiography, Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, ISBN 978-1-55709-079-9.

- Johnston, E.A. George Whitefield: A Definitive Biography (2 volumes). Stoke-on-Trent: Tentmaker Publications, 2007. ISBN 978-1-901670-76-9.

- Kenney, William Howland, III. ″Alexander Garden and George Whitefield: The Significance of Revivalism in South Carolina 1738–1741″. The South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 71, No. 1 (January 1970), pp. 1–16.

- Kidd, Thomas S. The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-300-15846-5

- Kidd, Thomas S. George Whitefield: America's Spiritual Founding Father. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Lambert, Frank. "'Pedlar in Divinity': George Whitefield and the Great Awakening, 1737-1745." Journal of American History (1990) 77#3 pp. 812–837 in JSTOR

- Lambert, Frank (1993), Pedlar in divinity: George Whitefield and the Transatlantic Revivals, 1737–1770, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-03296-2.

- Mahaffey, Jerome. Preaching Politics: The Religious Rhetoric of George Whitefield and the Founding of a New Nation. Waco: Baylor University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1-932792-88-1

- ——— (2011), The Accidental Revolutionary: George Whitefield and the Creation of America, Waco: Baylor University Press, ISBN 978-1-60258-391-7.

- Mansfield, Stephen. Forgotten Founding Father: The Heroic Legacy of George Whitefield. Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing (acquired by Sourcebooks), 2001. ISBN 978-1-58182-165-9

- Noll, Mark A (2010), The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield and the Wesleys, ISBN 978-0830838912.

- Parr, Jessica M., Inventing George Whitefield : Race, Revivalism, and the Making of a Religious Icon (University Press of Mississippi, 2015). 235 pp.

- Philip, Robert. The Life and Times of George Whitefield. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 2007 (reprint) [1837]. ISBN 978-0-85151-960-9

- Reisinger, Ernest. The Founder's Journal, Issue 19/20, Winter/Spring 1995: "What Should We Think of Evangelism and Calvinism?". Coral Gables: Founders Ministries.

- Stout, Harry S. The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism. Grand Rapids: William B Eerdmans, 1991. ISBN 978-0-8028-0154-8

- Whitefield, George (1853), Gillies, John, ed., Memoirs of the Rev. George Whitefield: to which is appended an extensive collection of his sermons and other writings, E. Hunt.

- Whitefield, George. Journals. London: Banner of Truth Trust, 1978. ISBN 978-0-85151-147-4

- ——— (2001), The Works (compilation), Weston Rhyn: Quinta Press, ISBN 978-1-897856-09-3.

- ———, Lee, Gatiss, ed., The Sermons (2 volumes), Church society, ISBN 978-0-85190-084-1.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: George Whitefield |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: George Whitefield |

- Bust of Whitefield at Gloucester City Museum & Art Gallery.

- Biographies, Articles, and Books on Whitefield.

- Lesson plan on George Whitefield and the First Great Awakening

- 59 Sermons by George Whitefield at the 'Asia-Pacific Institute of Biblical Studies (APIBS)' "103 Classic Seremons – Library"

- 38 Sermons by Whitefield at the 'Reformed Sermon' Archive

- George Whitefield's Journals project – Project to publish a complete edition of Whitefield's Journals

- History of Old South at Newburyport, Massachusetts

- George Whitefield preaches to 3000 in Stonehouse Gloucestershire

- Works by or about George Whitefield at Internet Archive

- Works by George Whitefield at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- George Whitefield at Find a Grave

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|